‘There’s the Greek word ekphrasis, the literary description of an image, the visual made verbal – often in a way as to vivify and dramatise that image. Ekphrasis, in its verb form, means to ‘proclaim or call an inanimate objects by name’. Samantha Harvey says she wanted to ‘call up’ that object, ‘the earth’ and make out its silence otherwise on the page ‘thunder and music’. [1] This is a blog on Samantha Harvey (2024) paperback ed.) Orbital Vintage, Penguin.

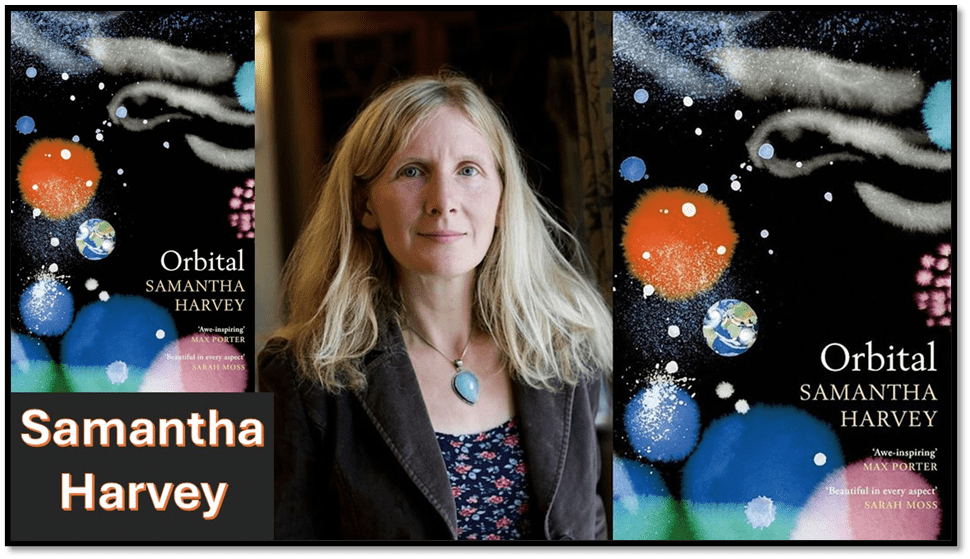

Before I write this as I intended to do for it is the last of the currently published books on the Booker Longlist., I just need to admit to a moment of déjà vu that troubles me somewhat. I like to blog daily but was only two-thirds of the way through Orbital. Since my other project, on Thom Gunn, was also a long way from ready, I wrote an answer to a WordPress blog prompt, asking me ‘What do you enjoy most about writing?’. That blog I put on this morning (read it at this link if you wish). In it, I said that about the qualities ‘writing’ makes available to you as a reader, summarising them in this paragraph:

This is at its best in the old rhetorical art of ekphrasis, the writing about a topic usually a painted or sculpted and silent about its own potential to meaning, for good or ill, in its use after its invention for wider purposes in Ancient Greece. If I have to think about how that is illustrated to me in my experience, it was in visiting last Friday the exhibition at the Bowes Museum in Barnard Castle that put together for comparison work by L S Lowry and Norman Cornish. One painting has haunted me since, and I think only writing about it. I think only writing will release those ghosts, embody them imaginatively as voices re-creatable in reading.

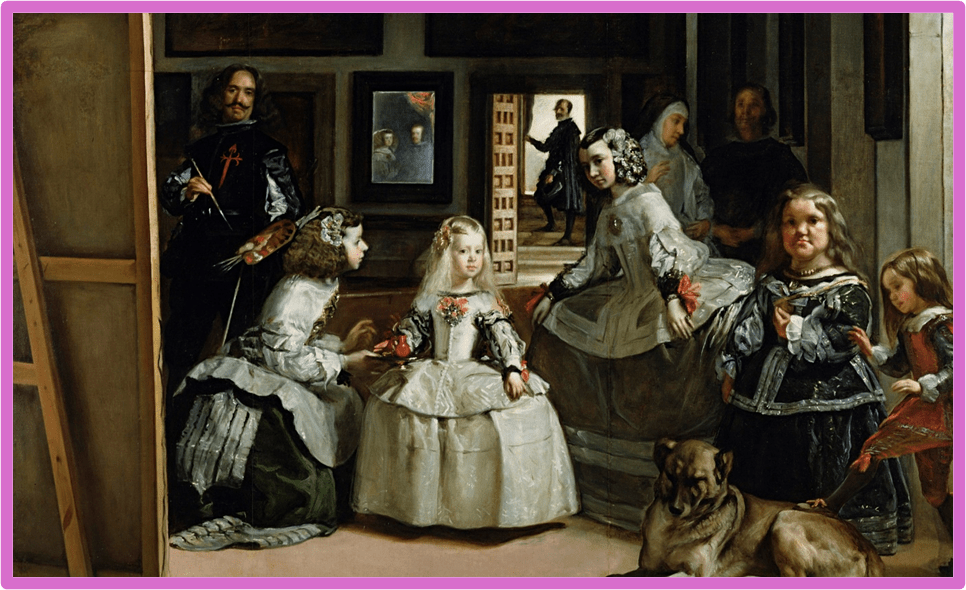

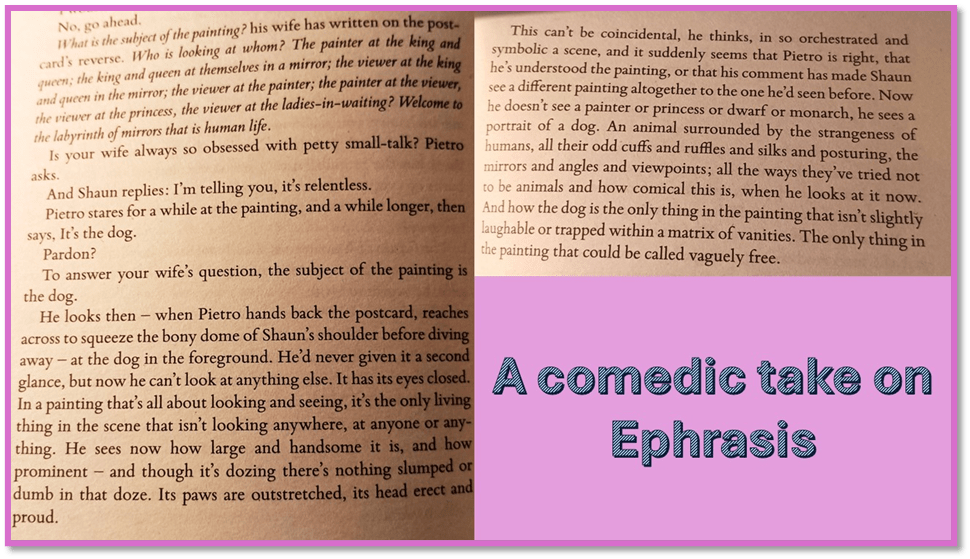

I wrote about the Norman Cornish painting and published it on WordPress. And then I walked the dog with my husband driving to Bishop Auckland first. On the way home I continued reading Orbital as my husband Geoff. On page 104 by then, I was amazed to find an episode that seemed uncannily to reflect the morning’s blog. In the novel, the astronaut Shaun thinks of the likelihood that he will divorce his wife on returning to earth from his earth orbital mission and turns to a postcard he had taken with him from her (one mentioned much earlier in the book) with his wife’s witing on the verso. That writing is printed in italics below on the page below. There is a reproduction of Diego Velázquez’ painting Las Meninas on the front.

The postcard was to remind him of a time when he met his wife in a class where the teacher talked on and on about the painting and he decided such forms of knowledge about the arts were not for him. When he looks at the painting again he does so in the knowledge of being prompted to comment on an upcoming moon-landing by different astronauts. The question Is: ‘with this new era of space travel, how are we writing the future of humanity?’ I had a double-take as I read that – is that not, I thought, a version of the question about the purpose of writing I had written about earlier. As I read on, Samantha Harvey shows Shaun re-reading his wife’s card and then jokily talking to his Italian colleague, joking about the unusual intensity of the writing for a postcard. ‘Is your wife always so obsessed with petty small talk?’ Pietro jokes ironically. But Pietro also answers by doing his own ekphrasis of the painting, as I had done with Norman Cornish. I photographed the pages. These I must write about when I finish the novel, laughing to myself, if a little spooked at the combination of issues of the purpose of writing and ekphrasis coming together. Here is a collage of the pages photographed (pages 104 – 5).

Back home from walking our dog Daisy, I finished Orbital in the bath. But even having determined a topic for my review did not stop me being spooked, for having finished the book, I read the Author’s Afterword supplied only with the paperback edition supplied to independent bookshops. Here Samantha Harvey makes it clear that she deliberately evokes the concept of ekphrasis and tied it to the episodes around Las Meninas, because of its reputation among philosophers who use it to illustrate their ideas, I had already though of Foucault using it thus when I determined to write of her using it. But just above her paragraph on that painting where she makes it clear that her purpose was to engage through her characters ‘investigating its possible meanings’, she explains ekphrasis in a paragraph whose first sentence. I use in my title to this blog and going on to tell us that the whole book is an attempt of an ekphrasis as the Greeks used it to investigate silent objects, not just pictures, and that the object she was taking was the ‘Earth’, that orb around which the astronaut characters in her book are orbital. Here is what I wrote in my title, citing Harvey’s ‘Afterword’:

‘There’s the Greek word ekphrasis, the literary description of an image, the visual made verbal – often in a way as to vivify and dramatise that image. Ekphrasis, in its verb form, means to ‘proclaim or call an inanimate objects by name’. Samantha Harvey says she wanted to ‘call up’ that object, ‘the earth’ and make out its silence otherwise on the page ‘thunder and music’. [2]

If the day’s accidental turn upon the ekphrastic was a coincidence, it still perhaps needs explanation, but explanation I cannot give. What remains clear is that the narratives, all from the perspective of each of the astronauts about what ‘Earth’ means top them are a kind of dialectical ekphrasis – a conversation, if sometimes unconsciously so to some of the more private participants, about characters ‘investigating its possible meanings’, and, in consequence Samantha Harvey’s purpose in writing this very book. The aim of the book is to write the earth into words and stories that make any reader understand it better and seek to contribute to the development, rather than the death of, its meaning.

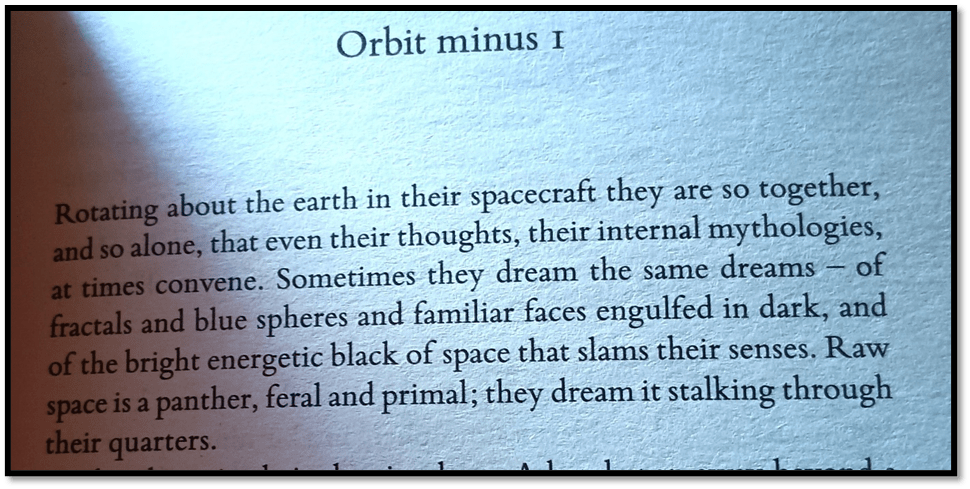

Hence the stories of mortality around the fact that Chie’s mother has died whilst she was in orbit and will be buried in her absence, about the tsunami and the hurricane which caused it, which all the astronauts see in process from their space vessel but cannot intervene in it other than in beaming back visual material to earth, to people whose ability to intervene is as limited. Stories of individual and mass death, or evasion of these, make the meanings of the earth hang on notions of extinction, and the past effects of human actions on the current and future environment. Not only their observations but their dreams carry an ekphrastic purpose – sometimes not just about the mortality of the body but the endurance of abstracts like desire, love, political antagonism and loyalty. Even the experimental mice whose bodies will be sacrificed to test the physiologically enduring consequences of weightlessness help. What does it mean that from their point of view they eventually lose fear of weightless conditions and learn to, as it must seem to them, fly.

This is a book that really exists best on the level of a kind of folklore philosophical thesis. It is written in readable prose that is also often extremely beautiful; lyrical at points, not least in the first chapter (‘Orbit minus 1’). Here not only the earth is turned into meaning by ekphrasis but also, as elsewhere ‘space’, that vey obscure subject, even to philosophy., but here turned not only into meanings but also feelings and into sense responses – very visceral ones:

How we see and interpret never need be entirely an individual thing and this is an idea played with symphonically through the piece, which is, after all, somewhat like music in nature. Astronauts are ‘so together and so alone’ simultaneously, attempting to understand through any available cognitions (such as fractals and spheres), hallucinatory material like dreams and the feel of invisible energy on their senses. Sometimes animals are the best interpreters, like the panther not least because so easily an endangered species. But I want to end by returning to Las Meninas for Pietro’s ekphrasis of it seems apt to my current running discourse on the function of animal consciousness in art, but also because it helped me see the picture anew.

Lots of viewers focus on the dog in Las Meninas, but do it rather guiltily, for isn’t this rather too sentimental a subject when the demands of Imperial Kings and Queens, heiress Infantas, suspicious courtiers at rear doors and the King’s own painter in Especial, who after all painting this picture of him painting another picture.

But Pietro puts us right, only for Shaun to widen the ekphrastic value of concentrating on this dog and its gaze, in contrast to the gaze of the humans that is the subject of Foucault’s ekphrasis of the painting in his opening to the work The Order of Things. What Shaun sees and justifies seeing is:

An animal surrounded by the strangeness of humans, all their odd cuffs and ruffles and silks and posturing, the mirrors and angles and how comical this is, when he looks at it now. And how the dog is the ….only thing in the painting that could be vaguely call free.[3]

And let’s face it, if you want to interpret the earth as home or anything else concepts of freedom and being bonded or bound matter. Without sorting them out we will never save the world but only play at our games of growth, development and expansion until there is no ‘earth’ left because humans have strangled it by right of their proclaimed ownership of the world and its meanings.

This is a short novel but a portentous one. Is it Booker material? Let’s see.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Samantha Harvey (2024: Author’s Afterward’, paperback ed. Exclusive to independent bookshops) Orbital Vintage, Penguin.

[2] Samantha Harvey (2024: Author’s Afterward’, paperback ed. Exclusive to independent bookshops) Orbital Vintage, Penguin.

[3] Ibid: 105

2 thoughts on “‘Call up’ that object, ‘the earth’ and make out of its silence otherwise on the page ‘thunder and music’. This is a blog on Samantha Harvey (2024 paperback ed.) ‘Orbital’.”