‘To be a witness, to stand alongside, simply to have lived through these strange, beautiful appalling times, to have been a night-light, a mirror, a support – ….’. [1] This is a blog on Claire Messud (2024) This Strange Eventful History: A Novel London, Fleet.

Perhaps, one ought to be alert to the strangeness of such a novel for our time merely because people read War and Peace slowly through it – Chloe in 2010 the last generation of the Cassat family we confront directly in their consciousness of the world of the novel has just reached the death of Oblonsky just as her grandfather dies. We have followed her family since the story starts in 1940, only knowing the secret at the heart of this family (in at least it’s the minds of a loving Cassat couple in 1927) in visiting them in the Epilogue). Stevie Davis sums up my difficulties in knowing what I feel about this novel of obviously gargantuan ambition. Here is her summary of what, for me, are concerns in her review in Literary Review.

This is a realist novel with a philosophical dimension. It is also long, detailed and demanding. Don’t expect to read fast. Though it is occasionally prolix and repetitious, with long passages devoted to retrospection and elucidation, I counselled myself against skimming or skipping: I’d have missed nuance, choice lexis, the versatile use of third-person narrative known as oratio obliqua (or indirect speech) and structural devices of singular originality.[2]

Every word of this would, had I read it before I read the novel itself, would have alerted me to a novel that is not really one of our contemporary time but the kind of intergenerational network of fictionalised semi-autobiographical memory collation and networking that produced great novels in the nineteenth century – ones that made personal, interpersonal, community, national and international crises all chime with each other, as in War and Peace. Would I have read it – probably not – except that it hit the Booker Longlist, had I known that? It is clearly good enough to be on the shortlist, too, though I would not vote for it to go there. There is a sense in what Davies sees that we are committed to a task that is educative, or should be – like ensuring we have read a novel before a seminar and are open to its nuance and refined novelistic technique. The framework themes remind me so strongly of those novels, those which F.R. Leavis called The Great Tradition; those works where indirect speech is very commonly the main method of the novel since it allows us to enter into so many consciousnesses with our ticket of exit on show.

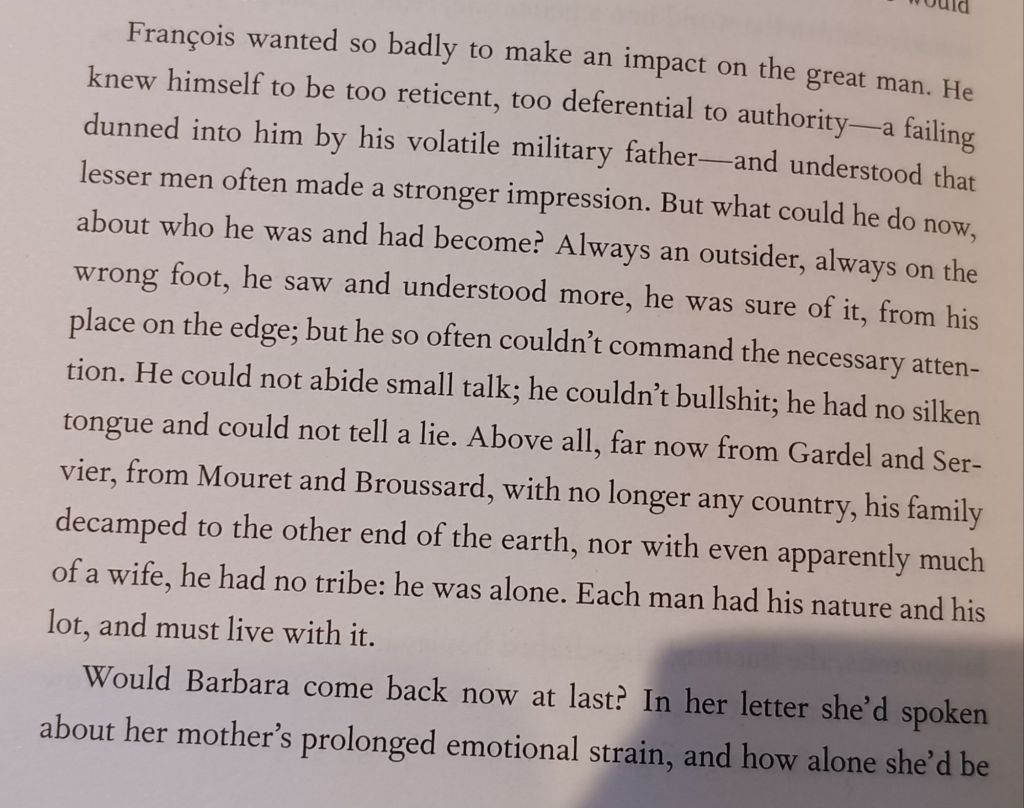

To test Davis’s idea, I opened the novel randomly. The passage I came up with (page 190 see the photograph below) concerned François as he worries about introducing Raymond Arun at a conference but at the same time fears that he is now more than geographically remote from his Canadian wife, Barbara, who has returned to Canada to care for her sick father.

We learn about Arun’s closeness politically to the right wing politics of De Gaulle, of his support from the young sociologist and intellectual Pierre Bordeau but we learn too that François’s concern relates not only to the symbolic ‘greatness’ of the French man but indirectly of the effects on François of his ‘volatile military father’, Gaston, in his early boyhood life, making him ‘too reticent, too deferential to authority’. And then a beautiful sentence, which shows me why I love François:

Always an outsider, always on the wrong foot, he saw and understood more, he was sure of it, from his place on the edge; but he so often could not command the necessary attention.

Going on to examine his incapacity for small talk and then shifting in the next paragraph to Barbara, this wondrous prose mimes the consciousness of a man, in intensely observed and of long duration passages of his life, lived through a trained alertnessof it that sometimes, in its rhythms, gives away more than in its content. Note that sub-clause; ‘he was sure of it’. It illustrates and internally dramatises a man reassuring himself precisely of a thing he is NOT entirely sure about. The sentence fails to make him even in ‘command’ of this moment of thought. I have to say, François is a great literary character – as fine as any in Henry James. Not long after my random page François is thinking about Tom Lehrer. You can’t get closer to felt history in memory.

However, there is so much (too much) to know, feel and sense in the reading for anyone to want much, or be able, to say any of it except in patches as above and that would take forever. Writing this novel must have been arduous. However, fun was had, clearly, in the invention of Denise, a character so alive I hardly know whom to compare her with in the literary canon. Here is a woman who fosters so many illusions one doesn’t know whom she wishes most to unconsciously hide herself from, though one suspects that her suppressed love of women is a fact that she half suspects as the root of her worldly alcohol pickled Catholicism. She functions only because of her recourse to showing the pain she goes through from a mental instability she can barely acknowledge but must. Her great long paragraphs span pages and have the volatility of a great character, like Molly Bloom, in James Joyce.

Every character has a richly distinct style in indirect speech even down to the variation in paragraphing to show the tempo and connectivity of the thinking and feeling of that person. Francois has the most conventional paragraph structure, but still suffers from not having taking the route in his intellectual life taken by his classmate in philosophy, Jacques Derrida. Many famous names touch on our characters fortunes directly and indirectly, staring with Gaston Cassat’s difficulties with taking General de Gaulle seriously as a leader of France in exile in 1940. We meet and hear the small talk of Jorge Luis Borges in Buenos Aires, Argentina, even. François is torn apart when a great French philosopher, Raymond Arun as we saw in the randomly chosen passage, and more so when Arun takes no notice of him at all, when he introduces him at a conference. This is a novel of diaspora, somewhat stimulated by the settler colonialism that made Algeria, where the novel starts, to be claimed as an equal Department of the French nation by France, equivalent to any in mainland France or the Corsican example. And then De Gaulle abandoned Algeria.

This is not then a serious review of the novel. I finished it, and found it fascinating, but it is not a novel I would revisit as I would Tolstoy or George Eliot whose work is of their time. As a whole, this novel is ghostly. It imagines the Cassat family as if it were a diaspora of a larger nation, and I feel I can’t even cope with the scope it wants me to attribute to the children of Gaston and Lucelinde. There is something too much, like the thing Leavis tried to pin down in George Eliot’s use of a Jewish theme in Daniel Deronda, in this prognostication of the story we have just read, and placed at the end of the Epilogue: ‘But, for their children, cast into a windblown century without God, where is there to be but alone and unseen, anonymous in the crowd? Who will carry us back to a place that lives only in the vast imaginary?’

I do not know what to make of a novel where that is one of the readings the author wants me to find resonant in the network of the family’s stories. I don’t regret reading it, but I did find it hard work, if full of wonderful things, as I have tried to show.

Should you read it? Your choice.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Claire Messud (2024: 405) The Strange Eventful History: A Novel London, Fleet.

[2] Stevie Davis (2024: 50) ‘No Direction Home’ in Literary Review (Issue 529, May 2024), 50.

2 thoughts on “‘To be a witness, to stand alongside, simply to have lived through these strange, beautiful appalling times, to have been a night-light, a mirror, a support – ….’. This is a blog on Claire Messud (2024) This Strange Eventful History: A Novel’”