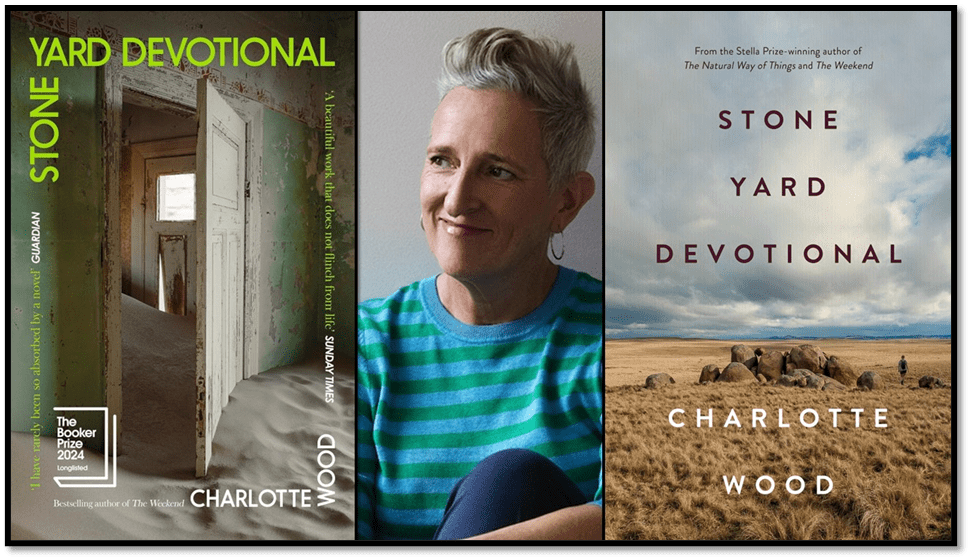

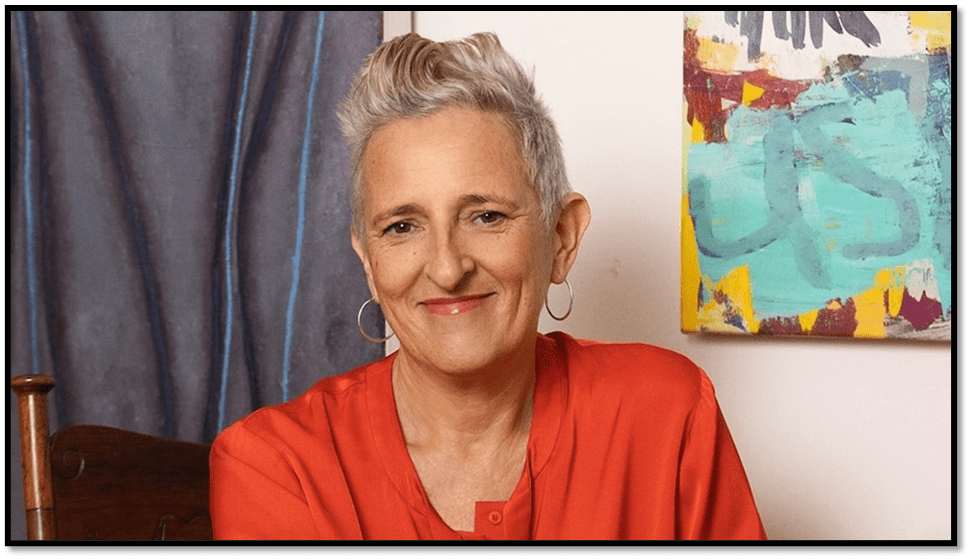

Charlotte Wood told ABC News in Australia that, for her, writing is a vocation. “There is something sacred … or holy about it. When you’re fully engaged in it, when you’re fully absorbed in the practice of it, there is an almost prayer-like aspect”.[1] I think only Iris Murdoch has worked with materials of moral philosophy like this previously, if in a very different manner and style, and still remained true to her stories. This is a blog on Charlotte Wood (2023) Stone Yard Devotional London, Sceptre Books, Hodder & Stoughton.

There are various ways to start off badly with this novel and I consider myself lucky in not having read reviews until I finished it. I think some reviews illustrate particularly the dangers of reading the book as indirect autobiography. Wood herself says of the novel, in an interview with Nicola Heath for Australia’s ABC : “It’s the deepest book that I’ve written … I trusted my instincts, and I kept trusting them”.

But a deep dive into a book is rarely be addressed by a simple listing of themes of different resonance in the book, though if it were Heath’s account is the best yet. Yet even that starts with relating the book to Wood’s recent life crises and how these may have prompted the novel, such as the discovery of her sister’s cancer diagnosis, followed shortly after by a further discovery that both she and their other sister had this diagnosis too. All the sisters have now recovered from the cancer and its treatment, which for Wood, she tells us with gratitude, did not involve chemotherapy. Both of the sister’s parents died of the same cancer of which they were found to have more treatable forms.

There are lots of ways that this ‘“psychic calamity” of Wood’s cancer experience found its way into Stone Yard Devotional’ in Heath’s words. For instance it might have fired the almost Sartrean ‘plague neurosis’ that references both a ‘plague of mice’ and indeed the setting during Covid lockdown which characterise the story . It might explain the grief of the strange and unreliable narrator at the death of her own parents, Beth (her stoic friend) and of her husband Alex (that triggered her to seek asylum) in a Catholic religious community, despite her lack of belief in religion other than as a symbolic and ritual form. But ritual form is just one of ways to appreciate life and seek to change its degraded forms in modernity. However, ritual forms are, in the novel, as important in native Australian communities as Eurocentric white ones.

In 1958, Iris Murdoch’s The Bell dealt too with the search for a better and more ethical way we might live together even without a belief in God within a religious community setting housing the religious and irreligious alike. Wood even explores similar models of moral life to those of Murdoch; citing even Murdoch’s favoured one, Julian of Norwich, as well as Simone Weil, even if she also includes Hippocrates and Joan Baez.[2]

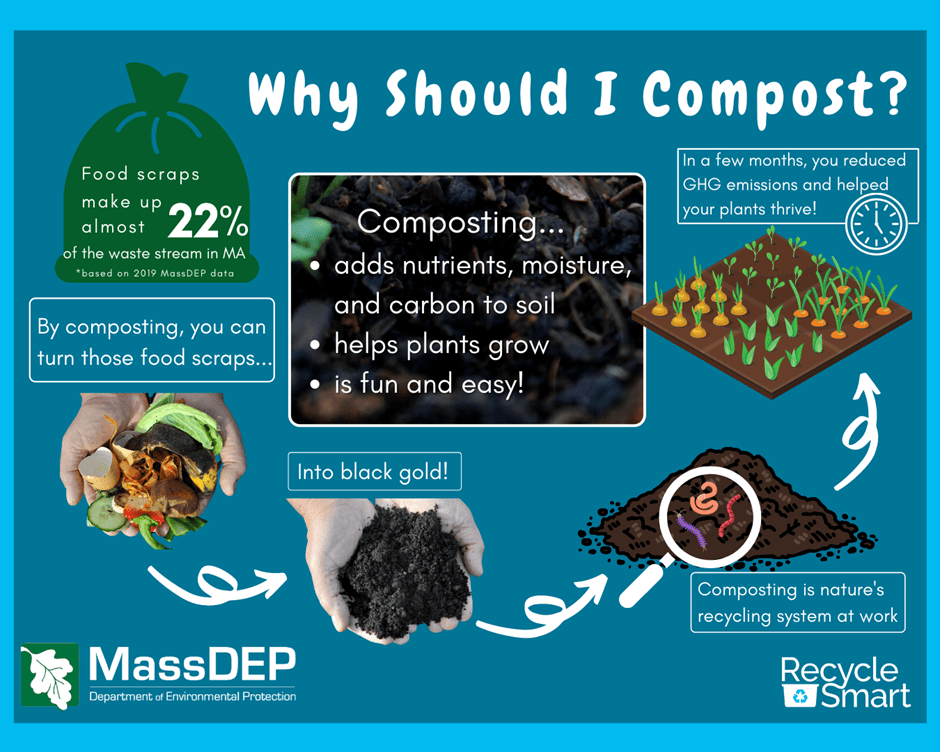

If the contemporary questions in Murdoch are largely about sexual and emotive companionship choices made in communities, in Wood they cover a wider range; some are quite mundane ones seen rightly as important contemporaneously such as finding the will to live without fast food and over-packaged mass-produced food products. On her first visit, and not yet a permanent resident, the narrator is asked as a guest at meal times to fill a ‘gaudy plastic’ basket, the ‘kind used in the supermarket express lane’, our first introduction to the horrors of plastic in the novel. To cap that however: ‘Everything’s packaged in individual sachets and servings – Nescafé. Sugar, vegemite, margarine, teabags. Teensy cans of Heinz spaghetti or baked beans, or tuna’.[3] When the narrator of these phenomena comes to live permanently in the community, this way of living simply using ‘packaged rubbish’ is made, largely by her own agency, her mission. That mission is to take the role over from Carmel, the nun in charge, and buy ‘in bulk, make things from whole ingredients’, Trying out her own prepared ‘dhal, or vegetable tagines’ unsuccessfully at first, eventually she takes over the kitchen chopping eggplant and soaking chickpeas’. Although chooks (chickens) still get killed the narrator stands out against animal husbandry that involves plaintive young ones who have to be removed from their mothers, like calves.[4] Nevertheless, increasingly the question in terms of the management of the domestic situation is about whether one can live without the world-destroying convenience of electricity, plastic containers and heavy machinery, for the effect of the plague of mice is to disable all those options of domestic convenience.

As the novel progresses, the narrator becomes less rather than more involved in environmental politics in the world – unsubscribing from her following of a raft of good causes in the care and husbandry of the planet and its species-diversity finally, all ‘causes’ associated with the more politically radical environmentalist, Sister Helen Parry.[5] Notably her unsubscribed causes include the oft mentioned Threatened Species Rescue Centre. Indeed their activity begins to seem itself suspect to her, even in environmental terms – ‘slurping up resources, expelling waste, destroying habitats, causing ruptures of some of some other kind’.[6]

The fundamental question then here is how to live ethically. Its formulation is at its starkest in contrasting and comparing the reflective and ritualised contemplation of a simple life followed by the nuns and their guests in their community, especially Sister Bonaventure, and the choice of engaging in effective missionary political action like Sister Jenny Tully and Sister Helen Parry. If to be an activist is to participate (or collude) in the human activities that consume the planet and its resources, the nuns can be seen to ethically superior for: ‘staying still, suspended in time like these women’. Their life ‘does the opposite’ of activism. ‘They are doing no harm.’ But as the narrator rests momentarily on such a declarative statement of ethical intent, she then characteristically too questions it immediately afterwards:

On the other hand, “Evil flourishes …”

(Also – what about all that packaging?)

This captures somewhat of the tone of the narrator, full of competing declarative statements relative to the moral life and how it is lived practically by humans and involving an almost absurd balancing of priorities. For instance, if ‘evil flourishes’, how significant an evil is commercial ‘packaging’ in plastics when other priorities call. The opposite of the nuns is ‘radical environmentalist nun’, Helen Parry.[7] However, even this choice is not a stark binary. It is only fundamental in a way that is nuanced for either Bonaventure, on the one hand, and the Sisters Jenny and Helen, on the other. For neither group is made up of effective models for their own choice of a ‘way of life’ without their being complicating contradictions, some of their own choosing but not at all and many dealing with contingencies of female oppression. Although historically the narrator is riddled with guilt for her collusion in the bullying of the marginalised child, that Helen Parry had been, at school, she even in the community of nuns interprets Helen’s energy of dynamic political action in the world with the malign interpretations and gossip in monastic communities that has ‘othered’ Helen entirely, almost to the degree of the Whore of Babylon, and certainly, guiltily on the narrator’s part, as apex predator:

… observing her in the media over the decades since, Helen parry comes across as cold, lacking in self-scrutiny, and immensely powerful. She is known for her intimidating gaze, and also a strangely flirtatious manner when challenged. Something ruthless and sexual emanates from her. In another era, if she wasn’t a nun, she’d be called a man-eater. Except her erotic charge is not directed only at men.[8]

That twist of sexual threat directed at her own kind – women – links her to the cannibalistic mice of the later novel; monsters who in desperation of action stop at nothing to survive. It sets the tone for SOME of the difficulties in the character of our unreliable narrator. What sets any determination to the ‘good life’ on a curved course for any option in life in the novel, however, whether in the aim of ‘doing positive good’ or merely avoiding ‘doing harm’ is the problem of responsibility to others and our attitude to the disruptive influences of the contingencies of difference (or in the terms of the novel, sickness, both mental and physical), loss and death and the contagion these cause cognitively, emotionally and in and on the surface (on the face indeed) of the body. This theme will be eventually tied to the narrator’s memories of her mother, thought by others to be doing things that were ‘good of her’ or on a ‘mission’, when she may never have been more than being kind to those who needed it.[9]

When the mice, in conditions of the scarcity of food as they enlarge in unsustainable populations, eat each their own dead, they eat only the faces. An eaten face is the fate too of a ‘peaceful dove’, as if only emblems of the good in people satisfied some appetites diseased by the primacy of unintended harmful life.[10] Even care of the vulnerable, like that of the mother-abandoned lamb, Violet, can turn nasty if our methods of living well are faulty. The most viscerally demonstrated loss in the community is of Violet, trapped behind corrugated iron with the nuns too busy in their rituals to hear her bleats, she re-emerges as ‘drooping woollen skin and bones, and the little skull of Violet, pieces of flesh still attached’.[11] Life has been left to rot.

But all these minor ethical shifts are early in the novel and, though difficult to negotiate, are on the surface of other more buried (or repressed) ethical issues. Though meeting the needs of bodily appetites continues to be a theme, the emphasis shifts from those dealt with on the surface of the community’s life to ones more hidden. There is an increasing awareness of crimes against the person, quite beyond Helen’s possible flirtatiousness (of which we see no sign in her in her visible appearances in the novel). In part this has something to do with the narrator who sees the ‘sinister’, associated with ordinary things, especially if of ordinary poverty, like that her mother addressed. The lady Denise helped by her mother is definitively ‘other’ in the narrator’s memory of her youthful perceptions: ‘There seemed something sinister about the little caravan parked in the dirt with the rocks and rusted things strewn about it,…’.[12] Dirt, garbage, waste crowd round her sense of what is potentially evil in her reportage. The constant memory is that we bury things in dirt and earth, so as not to have to confront them in life. Thus the burial of a baby chick killed by a rat recalls the burial of the neglected children supposedly looked after by Catholic nuns the world over, buried in mass graves because they ‘were called illegitimate’.[13]

Shady Cosgrove of The Conversation says in a good and intelligent review of this novel that the dubiety of the narrator is emphasised by her control of others and the burial of their point of view: ‘further emphasised by a lack of dialogue within the book. We are forced to trust our quiet narrator, because few other characters are allowed to speak for themselves’.[14] She points out that this narrator may not bury only facts of life (like ‘illegitimate’ babies or chucks killed by predators) but others in her own incomplete narrative. She clearly holds back things kept secret, as do many other characters in the novel, for good and bad reasons. Helen Parry’s knowledge of her own mother’s incarceration in an asylum is one of those facts of nuance that has to hid to the end.

Early on the narrator forewarns us: ‘Nobody will read this but me. Even so, I imagine there are things I am leaving out’.[15] one of the reasons the narrator thinks she visited the community in the first place was that she was: ‘Hiding’.[16] Yet she is full of stories of persons invited by their respective communities to go into hiding rather than expose their sexual or other lives, such as the suspected paedophile piano-teacher or even Sister Bonaventure, who mourns ‘something in herself, some ‘secret, wrestling work’ related to her past life with Sister Jenny, now bones’. In contrast, Helen Parry faced the world (in one of the many contradictory pictures of her from the narrator) and ‘remained utterly herself, hiding nothing’.[17]Of course we will discover Parry has hid things – perhaps has needed so to do. There are many ways of hiding – the bones of Sister Jenny are secreted in a box such that she can be ‘othered’ in death as she was in life as ‘that creature, the size of a large child, lying there dead in her box’. Is Jenny ‘lying? For the narrator feels that she anyway was ‘never visible to’ her.[18] Of her mother’s life ‘her secret self, even, the narrator confesses there were ‘many things that remained hidden from me’ and this included the fate of her dead young brother, Dominic.[19] And then there are more global hidden guilty feelings and secret sins that must be buried lest they stink, like a pile of mouse corpses. For instance, in an episode, we find the narrator in transit, looking out at the ‘brown bones of this land’, where there are signs of wear and social decay but also of threat like barbed wire that now looks delicate but was once oppressive. Returning home:

I heard an American professor say on the radio that his nation’s racist history was a reckoning in waiting, … it was the thing that must be confronted for the kingdom to be well.

And then, without explanation why, she remembers photographs of Catholic nuns ‘gripping small shoulders’, the shoulders of ‘rows of little Aboriginal boys’ and girls’.[20]

There is such guilt here, as again, in the story told of the unearthing of ‘ancient burial grounds’ containing ‘documented Aboriginal graves’ for a ‘private’ (but definitively white) housing development.[21] Amongst other things buried in, and sometimes unearthed from graves, are the sins of the religious, not only as the ‘carers’ of marginalised children, but of their own unspoken sex crimes. Sister Jenny (Tully) disappeared several times – for unknown reasons in the host community, but then in her exile in Bangkok, is murdered, it appears because of her role in a complex network of possibly sexualised relations with a priest who killed her (perhaps) and hanged himself. The story keeps coming across groups of people hidden from common view including the ‘child sex offenders, segregated from other criminals for their own safety’.[22]

Remembrance of death (but sometime social death only as in the last example) is at the base of the symbolic search of a way to live that must in any community include an ethical approach to the hidden and doubtful in human experience where passive compliance is not enough to live a true good life. Should we safeguard from knowledge of base things like death or sex or do we name them? The key metaphors are those of earth, dirt, bones, stones and rotting decay (garbage) and the height of ethics in the novel is both real and symbolic composting – the return to earth of ‘anything that once been alive’: ‘Anything that had lived could make itself useful, become nourishment in death, my mother said’: this is ‘reverence for the earth itself’.[23]

Indeed the composting debate revives throughout a novel, a theme lying behind that of nourishment by food, the ethics of its supply and consumption, the fallacy of its packaging, usually in un-compostable plastic in portion sizes that do not meet optimal human needs. The use of traps and poisons effect what goes into the food chain. There is such contamination in the world of this novel, that even the passage of time or distinctions of place become lost such that what is’ a great devastation’ occurring only rarely seems the stuff of ‘the ordinary whole of life’.

I used to think there was a ‘before’ and ‘after’ most things that happen to a person; that a fence of time and space could separate even quite catastrophic experience from the ordinary whole of life. But now I know that with a great devastation of some kind, there is no before or after. [24]

There is something primal here, as if under our coverings we might find truths we must face. Hence this is a novel where much digging occurs to find a safe base to hide things or to find the things we buried and have forgotten why. People are attracted to graves, drains, and ditches, emptied out thigs, like the man the narrator sees throwing himself down a drain.[25] Sometime we want to lost our desire or memories of them in these enclosed or underground spaces. One exemplary metaphor is that of ‘bedrock’ found after much digging but announcing a limit to further exploration, like the bones perhaps in a body. The narrator returns to her hometown, if to a queer version of it amongst the nuns for the same reason she returns to its landscape, which are an almost denuded skeleton of a landscape’s ‘bedrock’: ‘Although these plains bristle with a fine skin of pale grasses, they are almost as bare as bedrock, and I wonder if this is why I never came back till now’.[26] For though the bedrock is a memento mori it sometimes must be searched. Just immediately before the description just quoted, the narrator remembers that her doctor had used getting to ‘bedrock;’ to describe the condition of her present physical and mental illness. Asked why she was losing friends in her depression, the doctor says, who will herself weary of the narrator, that:

Your life has been stripped down to the bedrock, she said. It’s not their fault; their lives are protected by many layers of cushioning, and they can’t understand or acknowledge this difference between you. It probably frightens them. They are trying not to hurt you.[27]

People do not know how to do good because they are frightened of the despair they say but also because they feel some interventions are harmful. It is the same debate as between the Sisters Bonaventure and Parry. Not only holes bury things. So do ‘omissions’ in a story or silence that can’t be broken. Hence there is much just broken silence in this novel and the disturbance that noise causes in persons. Sometimes there is so much private silence one might commit suicide in it, a recurrent motif but eerie here in this early description of the religious community;

Noise is discouraged. Nobody would have to know, until the end of one’s stay, that a person might choose to end their life here on this clean carpet in a warm, silent room. At the moment I cannot think of a greater act of kindness that to offer such privacy to a stranger.

Is this a description of kindness or its opposite? It is not the narrator’s mothers version of kindness nor Helen Parry’s, the latter’s being officious at the best. For we are all uncertain about kindness or doing good and tend to ironize it, even Iris Murdoch in some characters. We think of it as a kind of ‘falseness’, an appearance or mask over natural isolated selfish motive. This is a point the narrator makes about her mother, saying how ‘it has surprised me, over the year, to discover how many people find the idea of habitual kindness to be somehow suspect; a mask or a lie’.[28] This theme of masking segues beautifully into the fact that wearing masks is supposedly the rule at the time of the novel, during Covid, or is useful to stem the stench of rotting mice. There is much play around when and how the funeral directors delivering Sister Jenny’s bones should wear masks or not and when.[29]

And it is this gap in belief that this novel dramatises, it inserts ritual – the needs to formally mark the great and lesser moments of the everyday, from the cycles of a day such as the ritual Catholic services of the nuns, the year or the great events of human life including death or deposition of the dead corpse (even a dead baby chuck). Without ritual, society is thin. So incapable is the council in organising permission for a funeral, with regard the inhumation of Jenny’s bones on private land, that eventually everyone agrees it must be done by voluntary agreement and outside human governance, in the light of a transgenerational belief that can include the native Ngarigo native Australians.[30]

Moreover the justification for such action is as much psychological as it is religious, perhaps more the former. This is a novel obsessed by the effects of neurodivergence, in its manifestations under labels of mental illness (neurosis or psychosis) or its psychosomatic effects like the ‘tight legs’ syndrome remembered by the narrator. The narrator in being taken for private therapy by her mother is being exposed to possible sexual abuse.[31] We use sickness to hide the things we fear (and thus make them more dangerously fearsome as in the last example) by mislabelling. A wonderful passage on the misapplications of the label ‘epilepsy’ conflates the complex relations between it and religious experiences, for if the ‘epileptic aura’ is like religious experience, in its abstract emotions or ‘hallucinations’, this does not mean that it is purely pathological or that ritualised responses are purely medical. The narrator instances Chagall, as later she does Matisse.

To call all vision ‘neuroelectric misfire’ is a gross reduction of experiential meaning.[32] Hence there is no dismissal of Helen Parry’s view, taking in some Buddhist thought, that the experience we label ‘illness’ is about not following the ‘life you are born for’. Her thought is compared to an artist who thought the same.[33] The story of Beth’s death is used as a means of comparing Beth’s stoic view of the quality of her own life and death with the ‘neurotic’ versions of this, including the narrator’s who failed to understand her.[34]

The complex passage dealing with all this matter relates to the narrator’s analysis of the ‘inhabiting presence in myself’ experienced during the ritual of Lauds in the community. The experience is both psychological and physical though aim to be spiritual. The problem is when we wish to label it: ‘This is either a ghost or God’, the narrator thinks, then remembers ‘the epileptic aura, and any idea of ghostly possibility falls away’.[35] However, it is notable that the ghost or God does not fall away to become an ‘epileptic aura’ by label instead. It is merely that the narrator learns that the possibilities that occur when body and mind work together in a social ritual are neither simply those of the body, mind or spirit, but an outcome resembling the latter that bodies and minds generate together and are no less real for that.

The problem of an ethical life is the result of a complex network of things, which includes dreams, the revival of old alliances for reinterpretation or the effect of a ‘plague’ or a traumatic memory bound up in a ‘delivery of bones’. That is meaningfully distinctive at one time when Wood’s narrator calls these episodes by the supernatural term, a term with less supernatural referents too, ‘examples of a ‘visitant’.[36] In the novel the supernatural often mimics the need for a deep ethical engagement about our responsibility for others: some of the guests or less clearly supernatural visitants. These may include Vietnamese migrant children who the narrator learns her earlier ill behaviour towards, or the feeling of a Second Coming of Christ OR Anti-Christ, the advent of despair or the preparation of a proper understanding of the forgiveness of wrongdoing in another.[37] At one point Helen Parry takes on the ambiguous form of a devil or the Pentecostal spirit.[38]

The most moving issue that runs through the novel is the level of retribution and forgiveness appropriate for wronged women to feel. At one point the narrator thinks of burning the religious community to the ground for the past wrongs of the Catholic Church.[39] Though the forms of Catholic ritual sometimes take on the language of the Hebrew Bible relating to retribution against enemies of God and the chosen, mentioned more than twice in this book: ‘The subtlety of the chant belies the blunt instrument of the words themselves’.[40] The ritual speaks a balance of understanding the heinousness of sins against you and learning to forgive where possible and as god or some other psychic force allows, as in the passage on forgiveness therapy.[41] Only in this way do we avoid the contamination that destroys not only the present but the before and after.

Much of this sound like a novel that redeems the religion that it also shows as wanting, but I think the point is that writing and literature (or other art) becomes one’s religion – as a recognition of its ability to weight the ethical and emotional issues in a version of the spiritual. Wood told Nicola Heath that the book felt like something of like a fundamental act of faith: “I was already on this path of writing a very spacious, spare kind of novel about things that I think are fundamental” Another words she chooses is ‘elemental’ to replace ‘fundamental’. Art is a way of resisting the fact that the narrator wants to “unsubscribe from her life”, as Wood says. Yet Wood also says that she shares with her narrator ‘a persistent “sense of futility” in trying — and failing — to change the world in the face of an intractable climate crisis’. If the aim is to combat ‘despair’ that human change is impossible: “yet, keeping up hope in the face of sometimes overwhelming evidence that we’re not winning this fight is hard.”

What Heath suggests is that Wood faces up to how ‘to live an ethical life’ by nuancing all these contradictions in ‘the sacred act of writing’ Heath writes:

Like the narrator, Wood doesn’t believe in God, although she was raised in a Catholic household.

And though she describes the mass she attended weekly with her parents as “stupefyingly boring”, she says the services helped shape her as a writer.

“Catholicism has all this elaborate richness of symbolism,” she says.

“Being washed in this kind of language, this rhythmic language of the Old Testament … it gets into your bones. You can’t escape it.”

For Wood, the act of writing is akin to religious worship.[42]

And though we will learn much, as with Iris Murdoch, from evocations from Julian of Norwich and Simone Weil, the key quotation in the book in my view is that from Matisse, quoted on a postcard the narrator once received from the artist’s designed chapel at Vence.

All art worthy of the name is religious. Be it a creation of lines or colours: if it is not religious, it does not exist. If it is not religious, it is only a matter of documentary art, anecdotal art … which is no longer art.

Of course here Matisse implies a better way of doing religion as well as art for them both to equate with each other. Something like this happens in this novel, as with Iris Murdoch at her best. Wood can laugh at this – as in the Lectio Divina episode – but she believes it nevertheless, reading through the deficiencies of her own narrator.[43] For me the most ghostly art is the music played at night by the mice nesting themselves in the piano of the religious community, in which their lives and deaths too will be cruelly but purposively implicit. What is holy is not a spiritual home as in religions but the ‘animal’ need for a home:

There may be a word in another language for what brought me to this place; to describe my particular kind of despair at that time. But I’ve never hear a word express what I felt and what my body knew, which was that I had a need, an animal need, to find a place I had never been but which was still, in some undeniable way, my home.[44]

I love this novel obviously. But whether it is Booker material. Who knows? It certainly is worthy, even to win.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Nicola Heath (2023) ‘Charlotte Wood’s latest novel Stone Yard Devotional tackles unresolved grief and a mouse plague’ in The Book Show (Monday 11 Dec 2023 at 6:00pm Australian). Text available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-12-12/charlotte-wood-cancer-diagnosis-stone-yard-devotional/103212600

[2] Charlotte Wood (2023: 240, 161, respectively & 26 for Baez & Hippocrates) Stone Yard Devotional London, Sceptre Books, Hodder & Stoughton

[3] Ibid: 16f.

[4] Ibid: 45f.

[5] Ibid: 152

[6] Ibid: 27

[7] Ibid: 114

[8] Ibid: 112

[9] Ibid: 31f.

[10] Seen first: ibid: 203

[11] Ibid: 181

[12] Ibid: 31

[13] Ibid: 42f.

[14] Shady Cosgrove (2023) ‘Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional poses big questions about goodness, purpose and sacrifice’ in The Conversation (online) [October 31, 2023 3.16am GMT] Available at: https://theconversation.com/charlotte-woods-stone-yard-devotional-poses-big-questions-about-goodness-purpose-and-sacrifice-216075

[15] Wood op.cit: 49

[16] Ibid: 14

[17] Ibid respectively: 80,153, 117

[18] Ibid: 137, 135 respectively

[19] Ibid: 145, 143 respectively.

[20] Ibid: 164f.

[21] Ibid: 190

[22] Ibid respectively: 54, 234

[23] ibid: 293

[24] Ibid: 210

[25] Ibid: 262

[26] Ibid: 34

[27] Ibid: 20

[28] Ibid: 31f.

[29] Ibid: 136f.

[30] Ibid: 191

[31] Ibid: 108-110

[32] Ibid_ 150f.

[33] Ibid: 224

[34] Ibid: 251f.

[35] Ibid: 183f.

[36] Ibid: 149

[37] Respectively ibid: 258f., 254, 168

[38] Ibid: 220

[39] Ibid: 165

[40] Ibid: 12.

[41] ‘forgiveness therapy’ in ibid: 276

[42] Nicola Heath, op.cit.

[43] Wood op.cit: 24

[44] Ibid: 66

2 thoughts on “Charlotte Wood says, “There is something sacred … or holy about [writing]. When … you’re fully absorbed in the practice of it, there is an almost prayer-like aspect”. This is a blog on Charlotte Wood (2023) ‘Stone Yard Devotional’.”