‘I wish I could tell my story with a sense of history as much as industry. … I can tell you that I am a man who is cognizant of his world, a man who can read and write, a man who will not let his story be self-related, but self-written’.[1] Percival Everett (2024) James London, Mantle. BEWARE SPOILERS.

Note : For my blog on Everett’s Booker shortlisted The Trees see this link.

Reviewing novels is a strange business. Let’s take a review from The Chicago Review of Books by Garrett Biggs as an example. Biggs makes a point of telling us that he had expected to write a very different review from the one he eventually wrote. Since the book was well publicised before it emerged as a ‘retelling’ of the story of Huckleberry Finn, in the novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, except told in the narrative voice and with the narrative perspective, not of Huck as Twain but of a fellow ‘runaway’, the slave Jim ‘owned’ by Miss Watson. Biggs expected to ‘hone in on the various harmonies and dissonances between Twain’s and Everett’s texts, and I have no doubt many reviewers will find great joy working through these tensions’. Yet, despite this expectation Biggs decided that, as a thought experiment perhaps, it was possible to relish ‘the extent to which this book can be read and enjoyed and written about without the slightest nod to its predecessor’.

Yet it is impossible not to start without one central problem in the comparison of texts. As Biggs tells us, Twain’s original book is ‘simply difficult to enthusiastically embrace, whether that be for his work’s gratuitous use of the n-word, or the reasonable desire to place other voices at the center of literary canon when it comes to novels so explicitly about race’ [2] Wikipedia tells us in its brief account of the reception of Twain’s book that the view of Professor Stephen Railton was exemplary of many views, including those of school learners:

According to Professor Stephen Railton of the University of Virginia, Twain was unable to fully rise above the stereotypes of Black people that White readers of his era expected and enjoyed, and, therefore, resorted to minstrel show-style comedy to provide humor (sic.) at Jim’s expense, and ended up confirming rather than challenging late 19th-century racist stereotypes.

The minstrel-show in fact becomes a key metaphor of Everett’s book in the exploration of the performative in race identities, and their relationship to stereotypes, but the key difference is in fact that Jim in Everett is highly educated. Jim in both books hears that his owner, Miss Watson, was going to sell him. However, in Everett’s story we are given an ‘unverified’ (though no reader will be free of the suspicion) that Miss Watson proposes to sell Jim because she suspected him being not only like her, or even superior to her, in intelligence and education. All of this hangs around the key theme of books in Everett’s novel.

Biggs associates this theme’s first appearance, on its fourth page, with the doubleness of Jim – his ability to act as white people expect him to but at the same time be aware of the ease with which he can demonstrate his superiority to them, other in the raw and violent power they hold over him in confirming his status as merely a commodity to be bought, used and sold. Biggs says James is:

a cerebral narrator, fiercely loyal father and husband, and enslaved man living in Missouri before the civil war. Jim is an expert in “[giving] white folks what they want”—speaking in a heightened (*cough* Twanian *cough*) diction and pretending to be unable to write or read. “What I gone do wif a book?” he says to the white Miss Watson, never mind the fact he is writing the very book the reader holds in their hands.

But the piece Biggs cites is crucial for it is the first sign that racism is based on white fear of the possible superiority of those subjected to it by force of economic and political control.

“Jim, I’m gonna as you a question now. Have you been in Judge Thatcher’s library room?”

“In his what?”

“His library.”

“ You mean dat room wif all them books?”

“Yes.”

“No, missums. I seen dem books, but I ain’t been in da room. What fo you be asking’ me dat?”

“Oh, he found some book off the shelves.”

I laughed. “What I gone do wif a book?”[3]

She laughed too.

Who laughs with, to and at this exchange? The ease with which James can throw Miss Watson off the evidence (for it is clear he does know what a library is for) is entirely because her stereotypical view of the ignorance of slaves can so easily be supported by a playacted game. We soon learn that James can not only read but read both comparatively – he knows Voltaire’s ideas relate to Montesquieu – but also read critically – in that he can look under words, such as those used in Voltaire to see the contradictions they hide: ‘“You’re saying we’re equal, but also inferior,” I said’. He says this in a delirious dream following a snake-bite to Voltaire, goes on to argue back citing Raynal on ‘natural liberties’ whilst still keeping Voltaire under the illusion that he is to be thanked for ‘being on your’ (Jim’s as a black slave that is) ‘side’ and being ‘an abolitionist of the first order’.[4] James remembers what he reads, reflects and even becomes superior to , and wary of, ‘further unproductive imagined conversations with Voltaire, Rousseau and Locke about slavery, race and, of all things, albinism’.[5] The issues of albinism indeed becomes an important thought experiment in James resolutions of some of the issues about ‘the constructedness of racial identity’ as Biggs calls it in his review’s first summary paragraph and even dream about what he has read but can write too

Moreover, more important than all these advanced reading skills (so speaks an embittered ex-lecturer not used to finding them as much as he might expect even amongst academic staff), James can write: ‘I read and read, but I found what I needed was to write’.[6] So important is that object, he achieves it even by knowingly putting a fellow slave at risk of his life for stealing it for him. That very slave, ‘Young George’, who is impressed a slave otherwise like him can write,[7] is killed – and most brutally – for that very act of trivial misdemeanour. It is not however a trivial if one is alive to the neurotic fear of white entitlement that its entitlement is not based on reality but on control of resources only (in this book and in life in my view). That brings me to my title quotation for it uses James most dense written articulation, once his pencil is secure from ‘Young George’ of the issue of identity: especially those on the cusp of issues of the sometimes ambiguous markers of binaries of class, gender, race and sexuality, all of which have some role in this novel.

I wish I could tell my story with a sense of history as much as industry. … I can tell you that I am a man who is cognizant of his world, a man who can read and write, a man who will not let his story be self-related, but self-written’.[8]

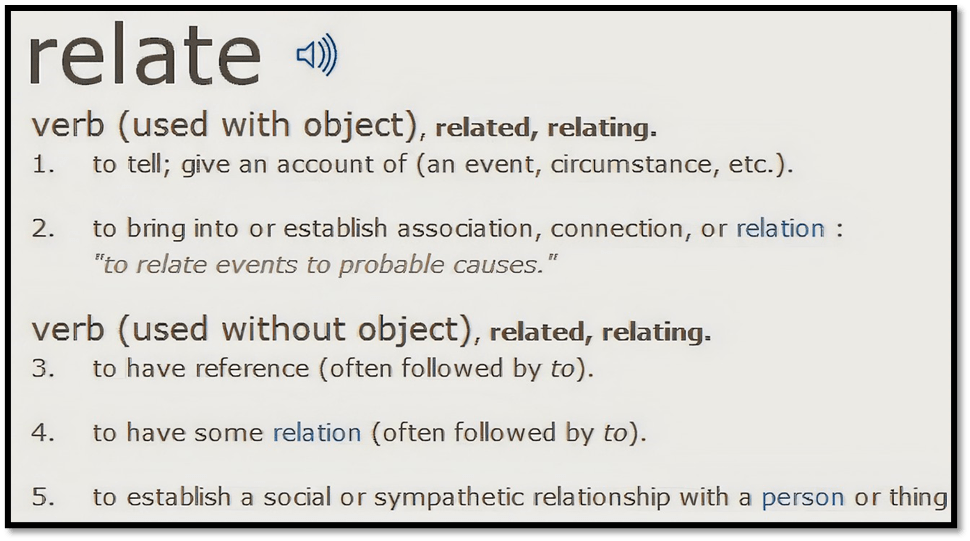

It is the kind of passage I often wished my learners in literature found more problematic than they did when I taught, for it is so throughout its whole italicised length: in which time and place, social relations, story and construction, knowing and being, independence and bondage to others are all made problematic. But my main concern, and one I kept coming back to on re-reading is the phrase :’a man who will not let his story be self-related, but self-written’. For what do these alternatives mean that James struggles to control. Part ly he does so because of the problems exposed by the term ‘related’, which in meaning and etymology differs as verb or adjective between a context in he act of storytelling and in the discovery of relationships between the apparently ‘unrelated’. That both these meanings are there I am certain for telling stories and discovering relationships – in families but also between different kinds of knowledge or forms of being – are central and, well, related.

The relevant webpage of Etymonline is, as always I find, extremely useful:

1520s, “to recount, tell,” from French relater “refer, report” (14c.) and directly from Latin relatus, used as past participle of referre “bring back, bear back” (see refer), from re- “back, again” + lātus “borne, carried” (see oblate (n.)).

The meaning “stand in some relation; have reference or respect” is from 1640s; transitive sense of “bring (something) into relation with (something else)” is from 1690s. Meaning “to establish a relation between” is from 1771. Sense of “to feel connected or sympathetic to” is attested from 1950, originally in psychology jargon. Related: Related; relating.

Things that are carried forward and back including physical books in a ‘sack’ that can be either read or written upon matter a lot in this novel but so do memories from books that bear a burden, as does that of Heidegger on James (surely an anachronism anyway of a major order) about being careful what you wish for.[10] Eventually Judge Thatcher is reunited with the lost or stolen books from his library in a satchel, with the power relationship between him and James momentarily reversed. That reversal goes for Jame’s proof that none of these books could have been read by Thatcher, and, if read, not comprehended in any way that made the concept of liberty meaningful (for the last book mentioned is surely John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty). James leaves Thatcher ‘ungagged’ to even prove the difference between them, though he takes away the books for he doesn’t think Thatcher will ‘miss them’. Asked what they are, James says:

“… A narrative of some slave. That’s one of them. It’s never been opened, so I know you won’t miss it. I don’t know why you have it. Candide. Something else by Voltaire. John Stuart Mill”.[11]

What Candide does in this novel is worthy of an MA Dissertation for it is more than once the topic of James’ dreams: its most famous line (“Nous devons cultivar notre jardin”) is spoken to him by a lean boy’ who ‘looked white’. Within a paragraph this boy is a girl and no longer ‘white-looking’, eventually transforming into the character from Candide, Cunégonde, whose role in the novel is never to be what she seems.[12] But this is not a MA Dissertation thankfully. I think I just need to stress that books read, remembered, critiqued, rewritten and remixed (with each other) is the lifeblood of this book. So what does James mean by identifying as: ‘a man who will not let his story be self-related, but self-written’. Primarily the idea to emerge first is that his story will not primarily be about identity (‘self-related’ in a very obvious sense) but about how the ‘self’ has meaning only relationally between possible people-positions (man, woman, straight, gay, black, white, bound and free) and in the spaces between multiples of diverse selves (whether in one body or many) . It is a story not ‘self-related’ but merely ‘related’ to otherness. And any self can write such a story, if they can write and not just orally report (or relate) their story for written signs are not tied to a body and voice that raise misconceptions of their meanings.

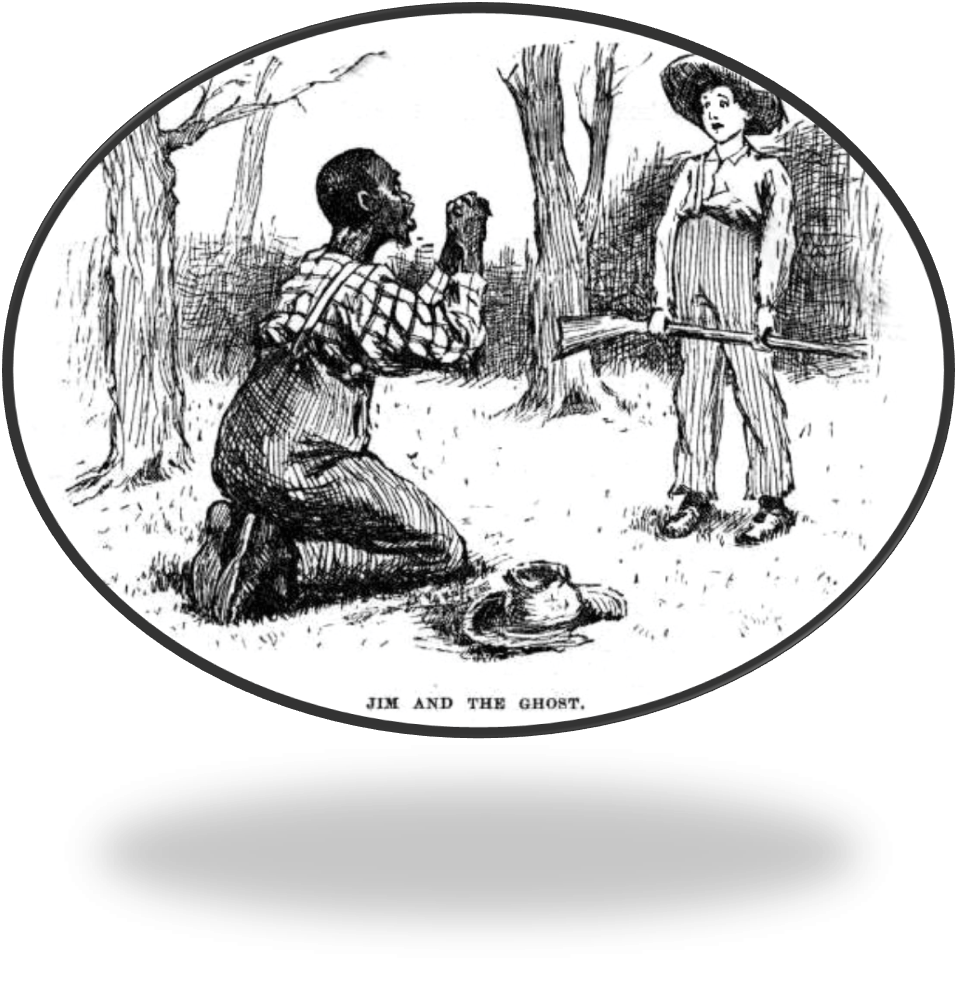

And this idea hangs upon a theme that enters from the beginning of the novel where James notices Huck and tom ‘playing some kind of pretending game’. These games ‘cast’ not only the identities of the voluntary players but other whose identity supports the fictive worlds of the primary players. For Huck and Tom to practice racial superiority then their actions, even the more passive one of ‘watching’ cast Jim as ‘a villain or prey, but certainly their toy’.[13] Similar slaves play up to masters by ‘waiting’ for them or on them, James notably playing the role cast for him by Twain as ‘Jim’, a role of extraordinary stupidity even more emphasised in the books early illustrations, a man more childish than the boy:

In this scene from Twain illustrated by E. W. Kemble, Jim has given Huck up for dead and when he reappears thinks he must be a ghost. Available at: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0e/Jim_and_ghost_huck_finn.jpg

To ‘play a little joke on ol’ Jim’ is to demean him, but being diminished is of less concern To James than having to talk and act like ‘Jim’ for James.[14] James not only enacts Jim he writes a script in which both ‘diction’ and content’, and of course grammar and style fits white stereotypes.[15] Other people do this too, often from a position of felt inferiority, like the Duke and the king, who are no less such role-players in Twain. But for a Black man the roles are cast for them: by white men in ‘Blackface’ or by the parameters of the slave role, that huck witnesses James break in his dreams and fevers so he is ‘talkin’ – I don’t know – you didn’t sound like no slave’. Slaves have to stay slaves even when passing a white nations ‘imaginary borders’ where he ought to ‘become’ a free man but does not.[16] In the Minstrels shows James has to adopt blackface in order to look like a white man enacting a Black man. Boundaries are transgressed though by nature. Some slave girls can be got up to look like slave boys to serve the heterosexual needs of their ‘masters’, like Sammy.[17] Huck can learn to cross gender boundaries also, although some women have already without teaching.[18]

And, in this novel, the truth that some ‘Black’ people are white allows for some, and this will perhaps include Huck not to give away too much, to ‘pass’ as White and gain that role’s status.[19] Class status is often about such passing amongst white people in the novel, and pretending to power you neither merit nor can sustain. Even death can be mimicked, as Huck does, and others. Every binary is not only transgressable but turned into a scale of multiple potentials rather than a binary. There are queer moments in the novel that either aren’t recognised or played as if they were not ‘queer’.[20] It is possible to be on more than ‘one ‘side’ at once when some binaries enforce themselves like the north and south of America in the civil war and the ‘slavery’ question, and abolitionists are still racists. Huck, tutored by his mentor-cum-father becomes ace at this. And James realises that whites are whites on each side of the binary: ‘I considered the Northern white stance against slavery. How much of the desire to end the institution was fuelled by a need to quell and subdue white guilt and pain?’[21]

There are special reasons why James needs to mentor Huck, subtly, but they involve coming to terms with white guilt and pain too:

“I never thought of that,” Huck said. “I never dreamed I could git you into trouble. Why would you want to kill me?”

“Dat don’t matter none to white folks.”

“I don’t like white folks,” he said. “And I is one.”[22]

White guilt and pain is not anti-racist revolution of thought. The true revolution comes when everyone realises that the lies we tell each other and secrets we keep hide truths about the fact that binary labels are just labels.[23] Is a live where we do not have to decide ourselves possible. This is a dream of a novel that KNOWS it is a dream. It is caught up in James’s words to Huck: “Just keep living,” I said. “just remember, once they see you, or see me in you, you’ve been seen. I know you don’t understand. But you will one day.” [24] There has never been a better definition even in praxis od relational identity – a positive way of seeing ourselves in each other and vice-versa, taking into accounts the misconceptions that arise from accidents and contingencies, like variations in sex/gender, status, skin colour, race and class. In a sense we have to write our relational self, taking care that when we write our first words’ that you truly want and try to ‘be certain that they were mine and not some I read from the judge’s library’. [25] This is probably an impossible task like all attempts at ‘certainty’. All we can do is to live in a way that is not ‘self-related’ but relationally-related, as our adoptive chosen families where binaries dissolve into the many we love, even the living and the dead. There are so many of these latter lost in this novel and this is a subject of this novel.

Strangely enough there is an element of it I love more than any other but have not mentioned because I don’t know how to evaluate that love in words. Throughout the novel the Mississippi River is personified, and that personified force characterised in all its moods and versions of being over shifting time and space. Its ‘force includes its capacity for apparently facilitating rescue but sometimes doing that by bringing about death by drowning. This aspect of the novel must be meaningful to Everett although its meaning is not entirely a thing of discourse, rather than a somewhat stoic attitude to the unevenness with which time and space are experienced and negotiated by human beings. When asked how the book related to Mark Twain’s achievement, Everett commented obliquely that both authors are aspects of the stories the River itself generates and that watch it together in silence would absorb their differences and commonalities:

“I flatter myself to imagine that I’m in conversation with Twain and writing the novel that he couldn’t write,” he tells Esquire. Still, he does harbour a fantasy of sitting side-by-side with Twain, watching the storied Mississippi River go by.[26]

This would be a worthy Booker winner. But read it whatever.

With love Steven xxxxxx

[1] Percival Everett (2024: 93) James London, Mantle

[2] Garrett Biggs (2024) ‘The Matrix of Performance in Percival Everett’s “James”’ in The Chicago Review of Books (March 29, 2024) available at: https://chireviewofbooks.com/2024/03/29/james-by-percival-everett/

[3] Percival Everett, op.cit: 12

[4] Ibid: 49f.

[5] Ibid: 52

[6] Ibid: 89

[7] Ibid: 88

[8] ibid: 93

[9] relate | Etymology of relate by etymonline

[10] Both physical books and memories from them are carried about on ibid: 73

[11] Ibid: 293

[12] Ibid: 276f.

[13] Ibid: 9

[14] Ibid: 11

[15] Ibid: 253

[16] See ibid: 5, 5, 218f., 286.

[17] Ibid: 210f.

[18] Ibid: 54, 60.

[19] Ibid: 150f.

[20] Ibid: 164, 177, 179

[21] Ibid: 286

[22] Ibid: page number lost

[23] Ibid: 255

[24] Ibid: 256

[25] Ibid: 55

[26] Adrienne Westenfeld (2024) ‘Percival Everett’s New Novel Is Destined to Become a Modern Classic: an interview with Percival Everett’ in Esquire (UK) Available at: https://www.msn.com/en-gb/lifestyle/lifestylegeneral/percival-everett-s-new-novel-is-destined-to-become-a-modern-classic/ar-BB1kab7M?ocid=msedgdhp&pc=U531&cvid=29164d0dd5434b9eb04ca7e322c6bca6&ei=68

2 thoughts on “James is ‘a man who can read and write, a man who will not let his story be self-related, but self-written’. This is a blog on Percival Everett (2024) James London, Mantle. BEWARE SPOILERS.”