‘Full fathom five thy father lies’:[1] Sometimes sprites are wicked creatures but even they know not to disturb the deeply buried bones of one’s father’s reputation and accuse him (openly) of lying. Nevertheless, Ariel in The Tempest, like Puck, in that other great fairy play, knows: ’what fools these mortals be!’[2] This is a blog on Rose Boyt (2024) The Naked Portrait: A Memoir of Lucian Freud London & Dublin, Picador.

In Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Ariel sings:

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes;

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea change

Into something rich and strange.[3]

He sings a lie, but few want to feel ill of their father, even when the evidence of their imperfection and sometimes bad behaviour, even to the point of abuse, is well evident to them. It is a song about lying and the appearance of changing fragile mortal flesh into something not only ‘rich and strange’ but hard and unmalleable. In Rose Boyt’s book The Naked Portrait of the title refers to an adult portrait he painted of her, Portrait of Rose (Rose dates it 1977-8), which opens the book’s narrative shifting across and between temporal moments and episodes: ‘Nothing had been discussed, I just assumed I would be naked’. But with the subtitle it has, it also promises a portrait of its supposed subject, Lucian Freud, also naked – a story with nothing that can’t be exposed.

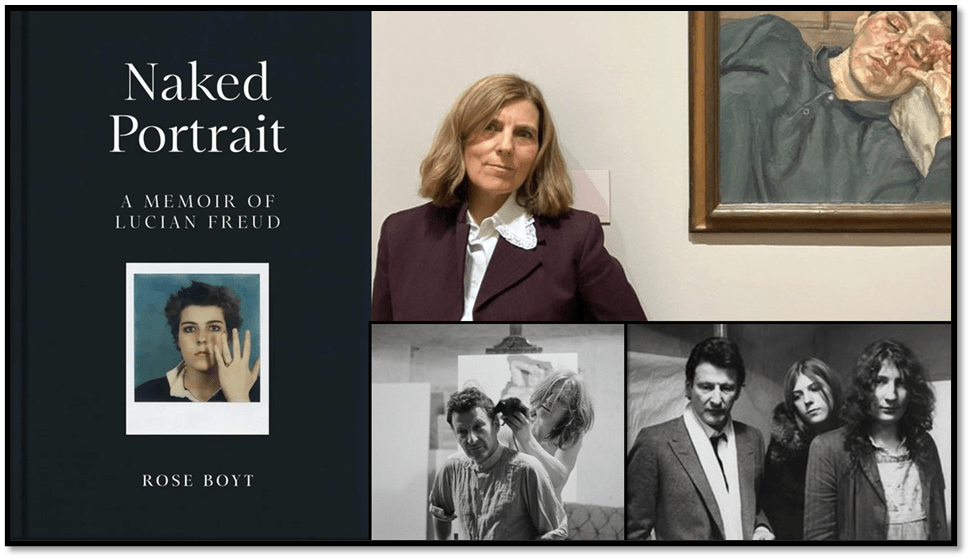

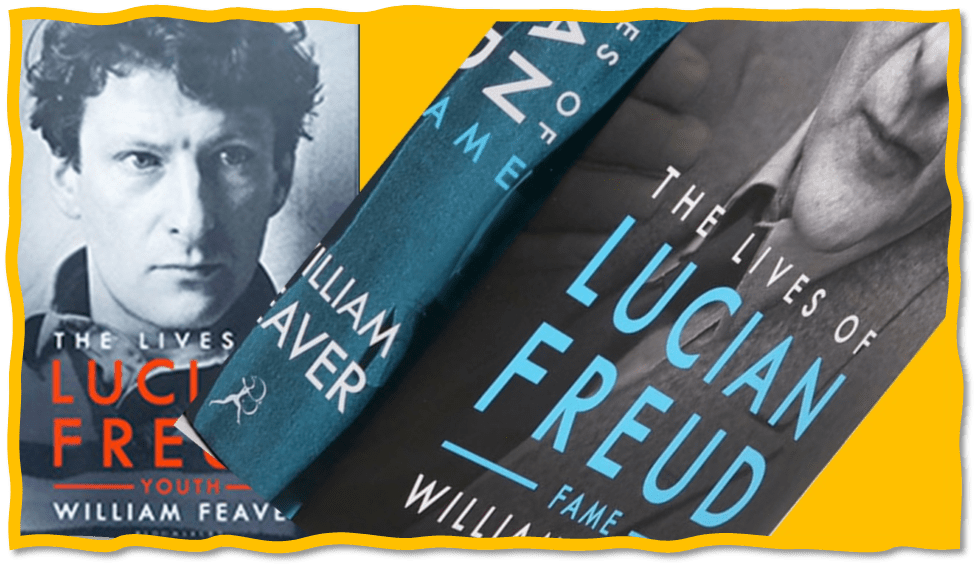

Rose Boyt, by the end of Lucian Freud’s life was a favoured daughter and the executor of his will. She is aware that much has been written and spoken of her father. For instance, she says of William Feaver’s huge two-volume biography (see my blogs on Volume 1 and Volume 2 respectively at these links) of her father that she doesn’t ‘want to read Bill’s version’ for in it she might unwillingly ‘hear my father’s distinctive voice parroted by the author in some muddled and mean-spirited imitative act’.[4] How should we characterise then Rose Boyt’s ‘version’ of that ‘distinctive voice’?

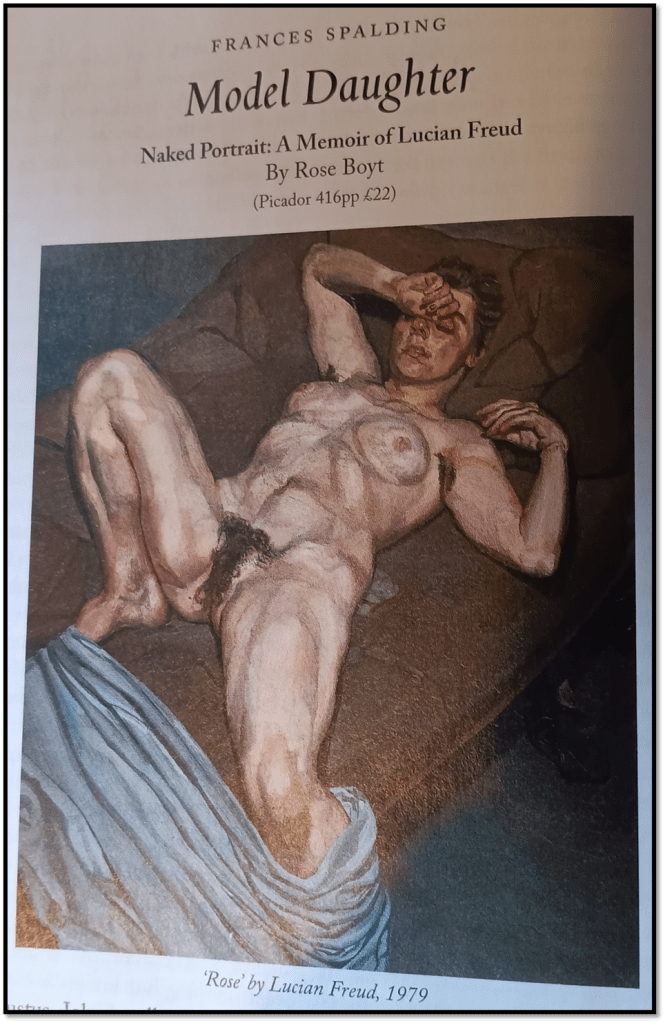

The opening of Francis Spalding’s (2024: 30) ‘Model Daughter’ in ‘The Literary Review’ (Issue 531, July 2024) ‘ 30 – 31 with ’Rose’ pictured

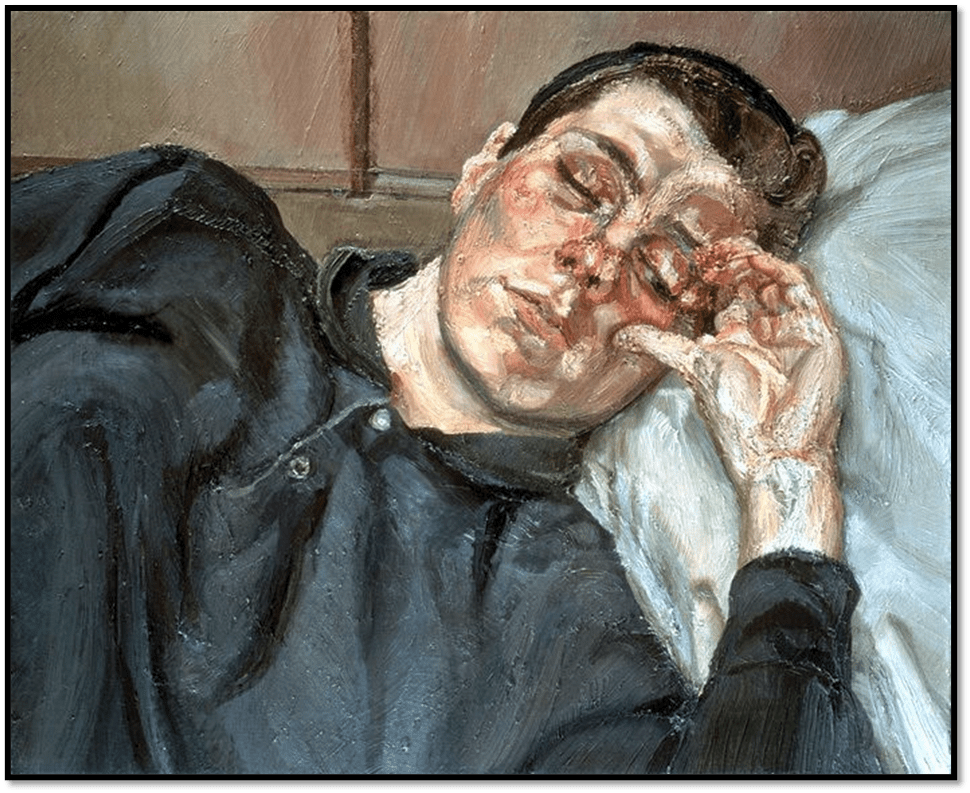

Going by Feaver’s partial accounts of her as witness and element in Freud’s life, we would think he knew both her and her father well, his picture of her role presents her as collusive partner of her father’s art, both wanting attention (his and that of others) and fearing and guarding herself from it: in the portrait already referenced (he dates it a year later than Rose 1978-9) Feaver says she is ‘lying back with a thumb laid across one eye warding off merciless studio lighting, a cloth snagged around a leg and toes (her suggestion, she remembered) as though restraining her a little’. [5] The gaze of studio lighting is not the only gaze one imagines the character Feaver creates of out of Rose might want to ‘ward’ off. Her desire to be presented as constrained and restrained is an artifice it seems but whose – Rose says hers, Freud said (to Feaver presumably) his. Rose says though that though she chose the pose and wanted ‘to know if he was happy with it’, she was ‘shocked when she looked at the canvas and saw what he saw’.[6] Does Feaver trust Rose? The adolescent Rosie can be distrusted in his picture – even the older Rose does that – but can the adult witness Rose telling her version of the story be trusted either by Feaver. There is always a problem in reported indirect speech whose interpretive point of view we are in fact receiving.

She was full of aggression, she remembered, partly wanting to be noticed by her dad, partly wanting to shout. ‘Where were you when I needed you, you bastard?’ She sat for him because she had time and , being adolescent, would do anything. She took her clothes off because that was the obvious thing to do: partly it was to prove that she was not going to be fazed by it. … Anyway, she liked the idea of being assertive.[7]

Which of the two Roses ‘liked the idea of being assertive’ in Feaver’s account? Was it the young Rose whose story is recounted through Rose AND Feaver’s filter, or was it the elder witness to her early life still trying to get the upper hand of assertive men. In her book, but still narrated through Feaver’s interpretive filter. Rose was suspicious of Feaver and tells us that the biographer insisted on urgently conveying to her that he had evidence, that he would use in his book, of her father’s ‘supposed sexual activity’ with W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender, whilst Lucian was a young man. Although Rose had been prompted to the possibility of Lucian’s past queer liaisons by a friend who had, not knowing her parentage, told her that ‘Lucian Freud was a homosexual’, she had dismissed this as a confusion in her friend’s mind between the reputations of her father and Francis Bacon. Rose is horrified somewhat by Feaver’s keenness to disrupt her beliefs in this respect, ‘motivated perhaps by envy of my father, who did not like him and paid him one million pounds not to publish’. But her belief in her father’s quite enormous heterosexual appetite gets in the way of her belief that this sex could be consensual. Yet again she is not ‘fazed’ for she goes on to hope that the ‘sex was consensual and did him no harm’.[8]

Rose’s solicitude for her father’s vulnerability is remarkable here and she notes that it is necessary to register this because both ‘poets were considerably older and he was a vulnerable adolescent’. Rose’s attitude to the approach of older persons to younger ones is anyway a theme of the novel. I blinked rather at her censoriousness view of a novel in which ‘ a young girl’ can be conceived to ‘want sex’ with a ‘patronizing old man’, but I suppose my shock was really because the novel referred to is Jane Austen’s Emma – even more so when Rose says that as a teenager she HAD ‘believed (she) was safe with Jane Austen, nothing obscene was going to happen’.[9] The word ‘obscene’ seems rather over-dramatic a rendering of the presentation of Mr. Knightley’s courtship of a woman who thought she had a mind of her own. To see something similar in Auden and Spender’s sexual interest in her father seems rather overcautious too, since she feels able to add to the half-sentence already quoted that this ‘dynamic he was to repeat with the boot on the other foot not just with Mum and Bernadine But Celia, and Katie and Sophie amongst others’.[10]

And indeed more recent anecdotal evidence has been used to argue that Freud could reciprocate sexual interest with male peers of his own age, such as Adrian Ryan and John Minton (see my blog at this link). The issue about Freud’s sexual range was sparked, despite Freud’s insistence on his own uncontrollable heterosexuality because Freud often speculated about such sex propounding in the words in his daughter’s diary that ‘it was very rare to find a man who had no homosexual experience or inclination, apart from himself of course’, and were he to try it, the boy must look like ‘a girl’.[11] He loved to hear however of Leigh Bowery’s experiments with anal insertions and recounted them back to his daughter, a daughter renowned, even by herself, for looking like a boy. She describes a period in which she looked after ‘her sister by another mother’ Bella thus: ‘I had a short crop like a boy and her waist-length hair was gorgeously lush, falling in soft waves round her sweet face …’. Bella wanted to chop her hair off. Rose resisted fearing Bella would look more boyishly beautiful than her.

Image of Rose, 1990.

Critics of this book, who tend to like it very much, see Rose as more innocent a narrator than I do. Frances Spalding in The Literary Review clearly places responsibility for The Naked Portrait overbold angle of vision on her genitals on Freud rather than Boyt, and does so despite Rose’s clear statement that this was not exactly the case. For her and other critics she was just one of the other children of the artist who were abused by his desire to paint people he loved naked and exposed, especially his many children: ‘Like Freud’s other children, Boyt both hated and loved her father’.[12] Peter Carty in The i newspaper merely assumes Freud’s ‘monstrous behaviour’ and pre twenty-first century unchecked ‘toxic masculinity’, that is best exemplified in his numerous largely uncared for children.[13]

Both Carty and Spalding register that Boyt loved Freud for his ‘conversation’ that could leap from Nietzsche to equine husbandry …. to deep character analysis. But when she read his diary after his death she remembered she ‘had forgotten all that sex talk, how often I just smiled and even laughed a little when I should have put my hands over my ears and screamed SHUT UP YOU SICK FUCK’.[14] That she did not push back on this talk, and its interpretation of her, is one of the mysteries of the narration, even the difference between the direct quotation from her diaries (of which there is an increasing amount) and the current older Boyt’s written interpretations. These different accounts are marked by different fonts but like Peter Carty I sometimes found the diaries over-exhaustive in small talk, though Spalding clearly did not.

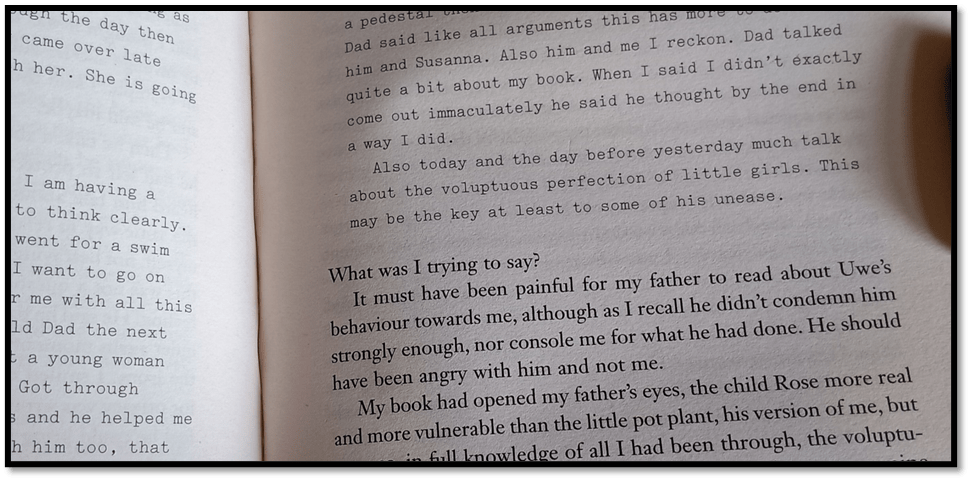

The method of intersecting contemporary diary accounts of Lucian and more modern commentary intrigues me however at very specific moments. When duplicating (or giving the appearance thereof by font differences) her daily diary from the 10th – 12th July 1990, during her sittings for the last shared portrait above) she retails through them how, Freud responded to a book by her that disclosed her rape by Uwe, her mother, Suzie Boyt’s partner following Freud’s rejection of Suzie. Her father asked her, adult though she now be, in this diary account to take into account Uwe’s terrible temptations because of, about which he ensured there was ‘much talk’, ‘the voluptuous perfection of little girls’. Suddenly the bold print of the author’s later attempt at interpretation cuts in – as you see in the photograph below:

A detail of pages 310f., as described, of Rose Boyt, op.cit.

There is so much to struggle with in Rose saying to us and herself: ‘What was I trying to say?’ She is weighing in her mind her father’s solidarity in the comprehension of the supposed power and uncontrollability of male desire once prompted by female voluptuousness. Was Freud acting as a sexually aroused man or a father. When he lived with her mother as her father did he feel as Uwe did about her? Perhaps, in his eyes, she was not perfectly voluptuous? Here are degrees of pain, and even guilt here that commonly pepper the aftermath of parental sexual abuse. It is difficult to read this coolly and without distaste for Freud. And, in the diaries, move so quickly to that subject from recounting a debate in which Freud paraded complicated feelings about Arthur Scargill’s conduct.

This is a book in which much remains unresolved. Freud paid for the psycho-therapeutic sessions with a man Rose refers to as Bridges, but often complained of the expense, both taking responsibility for part at least of Rose’s childhood trauma and its sequelae. However, I wonder if Lucian ever quite talked ‘cleanly’ (and I mean that in more than one way, for Freud’s discourse could be, to say the least, brutal about sexual function) about his own sexuality, even declaring (and Rose believes him) that he never read either Sigmund Freud’s (his grandfather’s) or those of his aunt, Anna Freud, on adult or childhood sexuality and trauma respectively. To him Anna Frwud was a challenging woman he knew but disliked . She in fact disliked him, he thought and declared, except when he was able to tempt her by one of his own American artist female admirers. Rose said in her diary however that she ‘knew Annie adored him’.[15]

There are other shocking things about Freud – how for instance, he shares with Rose that he stole much of the financial legacy of Sigmund Freud bit by bit (in gold coins from Marie Bonaparte and rich clients of the old man) without regard for his siblings with an equal right to it.

The coin Marie Bonaparte, a descendant of Napoleon and an analyst and friend trained by Freud, might have given Sigmund Freud in payment.

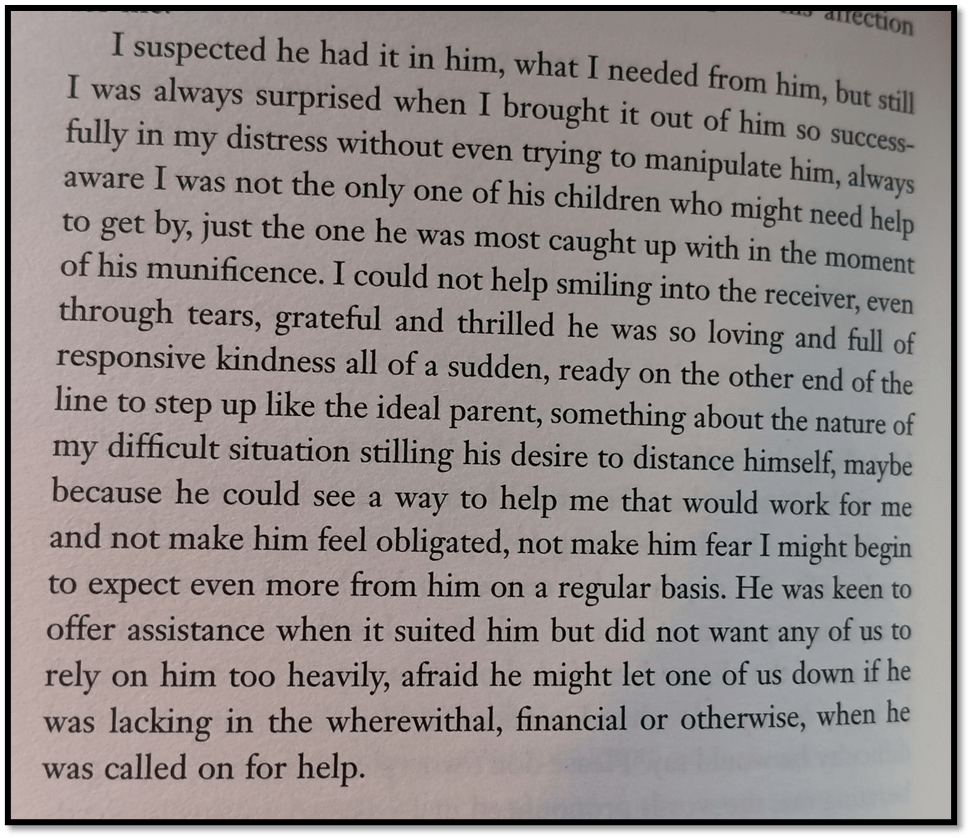

When I say however that Rose is no innocent narrator, I do not even hint at any complicity in her own abuse, but rather in its cover-up,. This cover-up is, in the most part, a covering up of her own awareness of the depth of the trauma she suffered and of her collusion with its continuance in her maintenance of an image of her father that is a long way from the truths she in fact knows . At intervals these truths emerge in her episodes of anger at him. But her usual tone about him is a see-saw of contradictions that never meld into the image of a DAD she wants them to do. Take this amazing paragraph for instance:

A detail of pages 358, as described, of Rose Boyt, op.cit.

There is no statement that is not equivocal or so qualified that it loses the force of a direct statement and remains a wish for the father you wished you had had. Even the suggestion that she is ‘manipulative’ or has that potential, shows how the passage rebounds back on Rose to lower her self-esteem as it fails to show him capable or even willing, unless there be distance between you and he or some means of extricating himself without too much overt display of shame. From stepping up ‘like the ideal parent’. Rose is ‘grateful and thrilled’ for the crumbs of love that fall from this table, whose ‘munificence’ when it came was to buy himself out of a tight corner, like the money he eventually and without expectation he paid Rose for sitting for him for The Naked Portrait, or the notice he paid her by showing his trust in her as his executor. Think of the thousand Rose knows he paid Feaver off to restrain that critic’s over curiosity about his sexual life. ‘I could not help smiling …’ Rose says knowing her reader finds her weak at that moment but capable of looking as if she were sorted out, which she is not, still as dependent on bridges as bridges is on Freud’s cash payments and thus herself doubly dependent on Freud whilst asking us to see her as gifted but a father, who underneath it all, was truly loving. For Freud was not a man who loved.

And I think the queer question is related to this, for Freud’s insistence on his over-heteronormativity and his over-reliance on youngest of women to prove his virility (a thing more of ideological straw than iron in reality) was surely the very inversion of the stories he told friends of his love for Adrian Ryan going well beyond the sexual fooling around and love for men with big hands and genitals but who eventually pass on of John Minton. Ryan’s biographer has no doubt of his interpretation of the ‘love/sex triangle’ between Ryan, Freud and Minton:

“It is more of an isosceles triangle,” said Machin, with Minton seeing the relationship through a casual sex lens. Freud and Ryan experienced so much feeling that “it frightened the bejesus out of them,” he said. “What they had, they just couldn’t accept it. But I think what they had was something so precious”.[16]

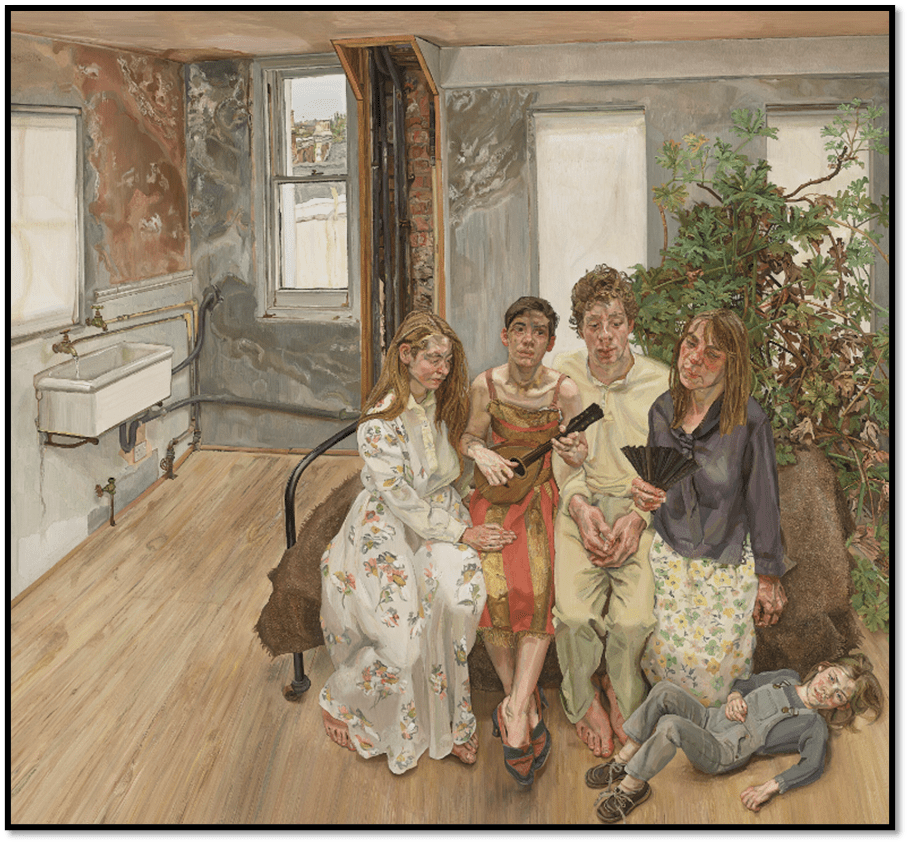

If some men love intensely in their youth and never truly again, it is perhaps because the safest thing in public and private life is to lie; and to lie’ five fathoms deep’ if you can, especially if you are a father (in Freud’s case, multiple times over). When he told Rose he could only have sex with a man if he looked like a girl, as Rose was oft said to look like a boy, Rose says that he ‘referred to the boy as ‘it’ in his sexual musings, dehumanizing the young person and releasing himself from responsibility’.[17] This turning oneself into an object – into flesh and even into meat, is not something he stopped doing with any subject who modelled for him. This is why Rose’s mother Suzie sometimes referred to Freud’s oeuvre, as collected in art books, as “Bluebeard’s Catalogue”, and why she preferred his paintings with ‘no people in them’ following her experience of being painted with her successor in Lucian’s ‘affections Celia Paul, but in the painting Large interior, W11 (After Watteau) being kept apart from Celia at opposite ends of a bed as objects awaiting disposal.[18]

Rose insists that Lucian loved his subjects, and that may be true as he tried to make the paint he used into their FLESH as recreated by him. But if he loved them, he loved them in the formal places and poses he mainly chose for them, though Rose thought she had won that one in her Naked Portrait. Roses final picture of her father is as being held as a small girl by him singing:

Oh, you beautiful doll You great big beautiful doll Let me put my arms around you I’m so glad I found you.

Of course, Rose admits, he had changed he last line in particular from Al Jolson’s : ‘I could never live without you’, for I suspect Lucian never wished to feel that ever again.

There is a lot in this book to think about. I scrape its surface only, on purpose. For ‘full fathoms five ….’. Bones of coral and eyes of pearl are both beautiful ideas.

With love

Steve xxxxxxxx

[1] Scene ii of Act I of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Cited in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ariel%27s_Song

[2] Scene ii of Act III, line 117 of William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream

[3] Scene ii of Act I of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Cited in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ariel%27s_Song

[4] Rose Boyt (2024: 212) The Naked Portrait: A Memoir of Lucian Freud London & Dublin, Picador.

[5] William Feaver (2020: 128f.) The Lives Of Lucian Freud: Fame London, Bloomsbury Publishing

[6] Rose Boyt op.cit: 1

[7] William Feaver (2020: 128f.) The Lives Of Lucian Freud: Fame London, Bloomsbury Publishing

[8] Rose Boyt, op.cit: 211f.

[9] Ibid: 235

[10] Ibid: 212

[11] Ibid: 211

[12] Francis Spalding (2024: 31) ‘Model Daughter’ in ‘The Literary Review’ (Issue 531, July 2024) ‘ 30 – 31

[13] Peter Carty (2024) ‘The Naked Portrait by Rose Boyt, review: Lucian Freud was a monster’ in the i newspaper (May 25, 2024, 6:00 am(Updated 6:01 am) Available at: https://inews.co.uk/culture/books/naked-portrait-rose-boyt-review-3061521

[14] Rose Boyt, op.cit: 193

[15] Ibid: 273

[16] Mark Brown (2021) ‘Exhibition brings to light young Freud’s love triangle’ in The Guardian 10th July 2021, p. 4., referring to Julian Machin (2009: 48) Adrian Ryan: Rather a Rum Life Bristol, Sansom & Company Ltd.

[17] Rose Boyt, op. cit: 211

[18] Ibid: 37f.