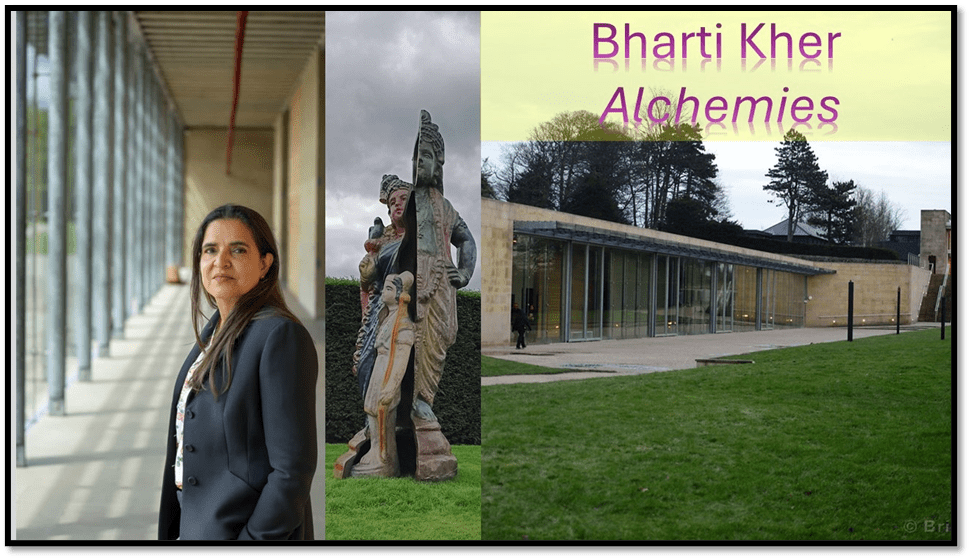

Bharti Kher (born 1969) works with, amongst other things including fabrics dipped in resin and hardened, ‘bronze casts of broken clay objects, reconfigured in new ways’ in the words of Laura Cumming in The Observer.[1] Art that is always interesting does not necessarily leave a strong impression conceptually, emotionally or networked on our senses. This was the case for me, and perhaps Catherine (she reserved judgement). This is from a series of blogs on a day visit to see the art in exhibitions at the Hepworth in Wakefield and The Yorkshire Sculpture Park at Bretton Hall Country Park. This is number 5 of 6.

I have seen many fascinating sculpture exhibitions in the Underground Gallery in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. I have blogged on one (see blog at link on name): Erwin Wurm, whose new sculpture of Balzac, with enormous reference to Rodin, adorns the ground near the Gallery now and which I had not seen before.

On this visit I got more than enough from Elisabeth Frink and more still from Leilah Babirye, even confining myself to exhibits at YSP on this day. But I failed to see those moments Lara Cumming talks about where:

when form and content come perfectly together, no texts are needed. The thin red line that runs the full length of the YSP galleries, just above your head, glows in the day’s sunlight. It is an artery of glass bangles: a beautiful female bloodline.[2]

I saw more of what she calls storylines behind artworks that are ‘entirely opaque’ were it not for the plaque giving information that was impossible to derive from the work itself. Catherine in contrast found an interest to follow that came from her own background in textile and fabric art, although she told me the interest may not have grown into a ‘liking’ for the art we saw. Catherine kept her counsel on this – knowing what a gossip I am in these blogs no doubt. LOL!

Take these works for an opaqueness in the background story.

I will use Cummings abstractions of the stories from the plagues. The work that appears on the left is a structure of loosely mortared bricks – the mortar being deliberately botched as if by over-hasty workers but possibly too with a backstory. You could go inside the structure – but only one person at a time. I did. Catherine did not. Cumming calls this structure ‘a solemn chamber of ultramarine bricks’ that ‘encloses the viewer’. Called The Deaf Room it is ‘made of 10 tonnes of glass bangles, commemorating the notorious Gujarat riots of 2002, where more than 1,000 people died, and women were raped and burnt’. The effect, stunningly moving as it should be, depends too much from this impossible to derive backstory. Likewise the ‘monolith of old radiators, titled The Hot Winds That Blow From the West’ depends too much on the environmental backstory implied by the title and in itself I didn’t like it, not even seeing the ‘heap of bleached bones’ Cumming sees in it.[3] Rather it is a repertoire of idea that need explication.

As Catherine and I finished lunch in the main building we went first to the semi-circular walled garden over the top and extended to the buildings added to the wall, where usually the piece de resistance of sculptures is shown. Here we find Djinn (see my photographs collaged below).

I never did quite work out what Djinn represented, though it seems not the mythical supernatural beings of Islam and of Eastern folklore and Arabian Nights stories. There is preoccupation, perhaps even distress – stilled into a pose of near-despair, but this piece or its character neither moved me nor raised my curiosity. Both are needed to seek a ‘backstory’. I did not seek one.

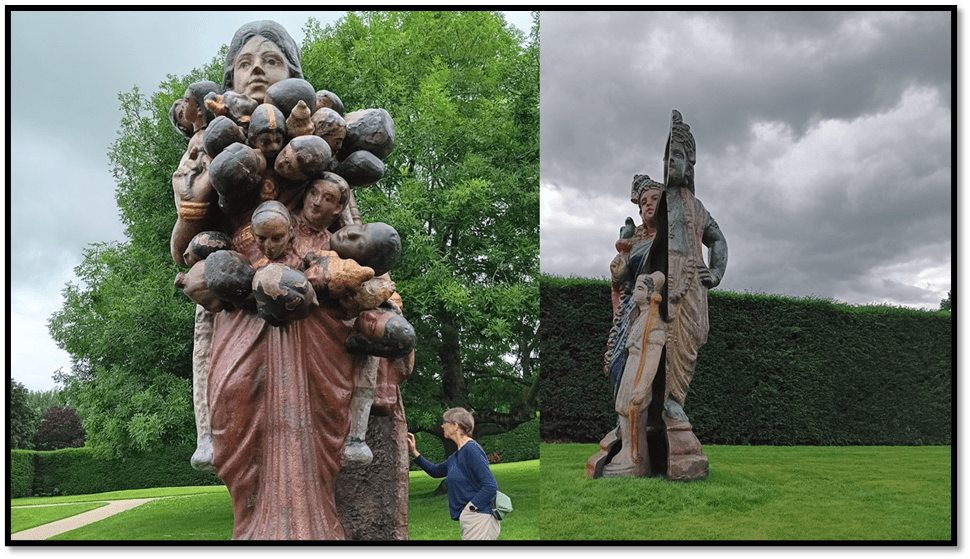

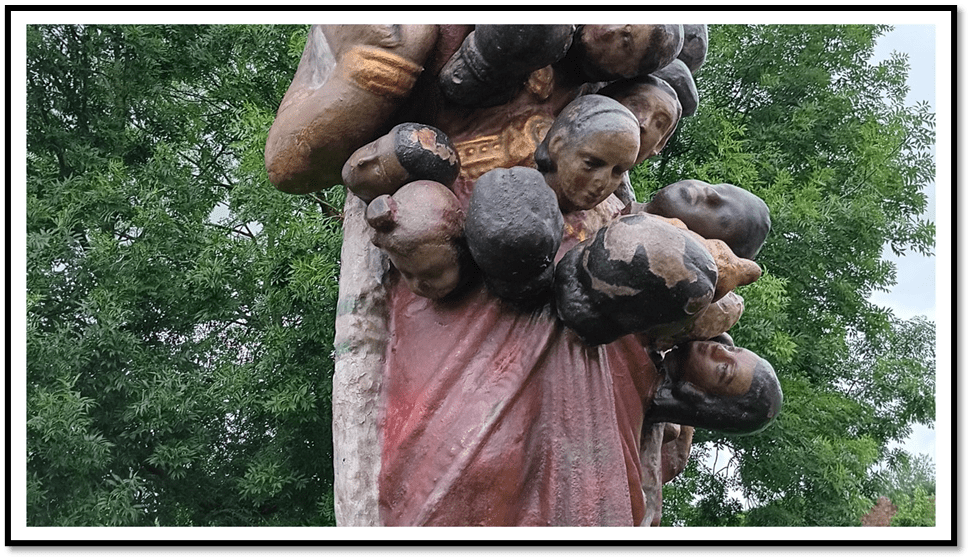

There are three other monumental pieces in front of the gallery. These are those that Cumming talks about – casts of fragmented Indian icons in which multiplicity in unity is achieved by a series of cutting and collaging techniques. They raise interest as to the media used but though they create double takes, they don’t repay it (for me at least) as does the Wurm Balzac pictured above.

The political backstories relative to colonialism in India and the burdens of Indian women, especially in bearing, or being forced to bear multiple meanings they might not be allowed either to enjoy or contribute to would raise the value of your engagement, but I didn’t feel invited to explore these.

Somehow the accretions were too clinical – the fragmentation achieved by too clean a cut of the casts to seem felt rather than thought-about pieces. Their references to Hinduism might help. I didn’t try.

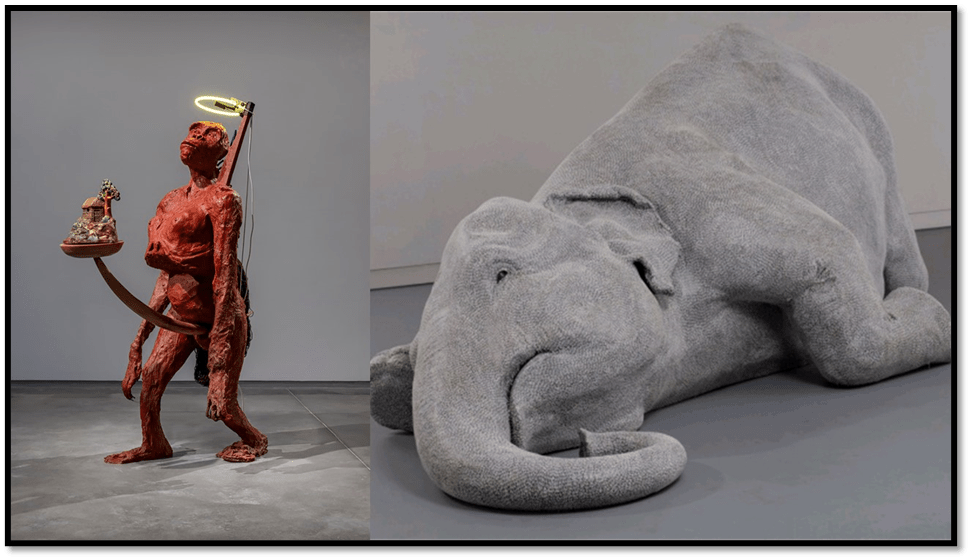

Inside the Underground Gallery, much was done with anthropomorphic ideas, related to (sometimes) the theme of fashion. The cattle head and its almost gilled necked is fascinating below. However, the model with the resin painted fabric stuffed in its mouth (to represent the silencing of women by (perhaps) male fashion and its abuse of women) failed because all I could think of here was Vivienne Westwood.

Moreover the animal themes, though full of pathos (especially the dying baby Indian elephant) did not engage me in their pathos. I felt strongly too obviously served ideas. The baboon with a halo and a weighty appendage fixed in through its vagina was, I thought, quite horrible without being illuminating.

Likewise other semi-animal divinely over-worked female motifs. They rouse curiosity but not enough feeling to make you care, so meretricious are they. I can’t speak for Catherine on this. She found herself engaged mainly in the means by which the fabrics were hardened and made glossy, though seeming still to flow on or from the body. Compared to my dullness in this exhibition, she had the better approach. Little did I know that from there I would see Babirye in the Chapel and wake up again aesthetically and conceptually.

But if Kher was a prompt to go to YSP, I can only be pleased for it yielded what I enjoyed much more: Frink and Babirye (but of course the Wurm Balzac too). Next time is my last blog on heartbreaking but life-affirming Ronald Moody’s sculptures.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

[1] Laura Cumming (2024) ‘Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life; Igshaan Adams: Weerhoud; Bharti Kher: Alchemies – review’ in The Observer (Sun 14 Jul 2024 09.00 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/article/2024/jul/14/ronald-moody-sculpting-life-hepworth-wakefield-review-igshaan-adams-weerhoud-bharti-kher-alchemies-yorkshire-sculpture-park

[2] Ibid.

[3] ibid