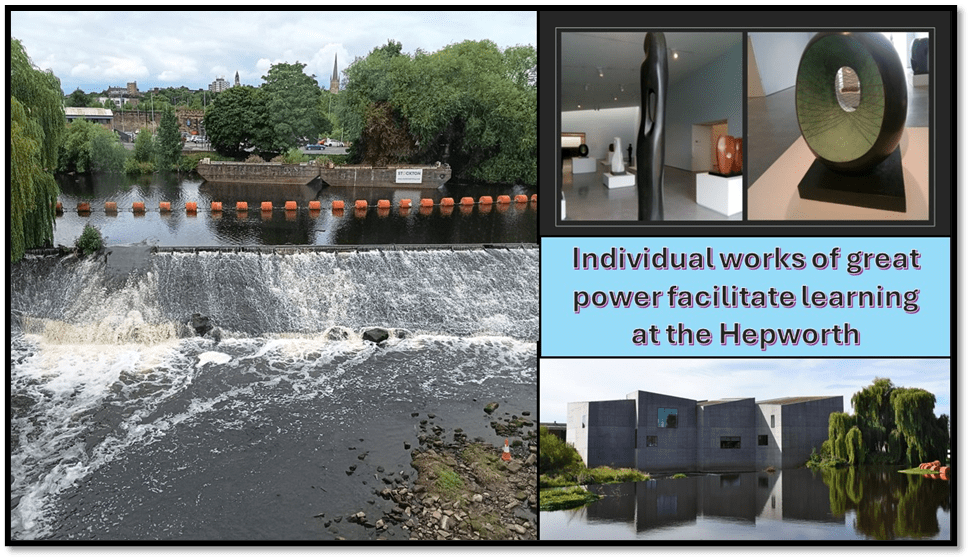

The Hepworth – a gallery where individual works of power can facilitate learning how to gain from a gallery visit – my way at least! This is from a series of blogs on a day visit to see the art in exhibitions at the Hepworth in Wakefield and The Yorkshire Sculpture Park at Bretton Hall Country Park. This is number 4 of 6.

The Hepworth is a remarkable Gallery, It is set between the river and a canal of a once great industrial city which was also the birthplace of Barabara Hepworth. I saw the best of the current Hepworth retrospectives here, that even the wonderful Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh could not match. You can read the Hepworth blog, relating mainly to Wakefield Hepworth Gallery retrospective at the link here. But the Hepworth has introduced me to much more – to Howard Hodgkin for instance and its glory is the stunning thoughtfulness of its exhibitions, of which by now I have seen many from people unknown to me and mysterious but somehow great like Alina Szapocznikow or, better known, Alan Davie and Hockney (see the link on their names for a blog).

On this day trip, myself and my friend Catherine (for Geoff decided preferred to care for our dog Daisy at home) were aiming primarily for three exhibitions: a much belated culturally retrospective of Ronald Moody (blog still in preparation as Blog 6 of 6 of this series) and queer artists of colour: Igshaan Adams & Leilah Babirye (blog 1 & blog 2 respectively) – although we saw Elisabethe Frink reprised too (blog 3) of this 6 blog series). The blogs are linked in the brackets before this sentence. Whilst at The Hepworth I was still relatively fresh and got a lot out of individual works, although I had intended to spend more time with an exhibition of oil painting by Sylvia Snowden. I did not feel energetic enough for this (so overwhelmed was I by Adams and to Moody in a quieter respect) but did learn from her.

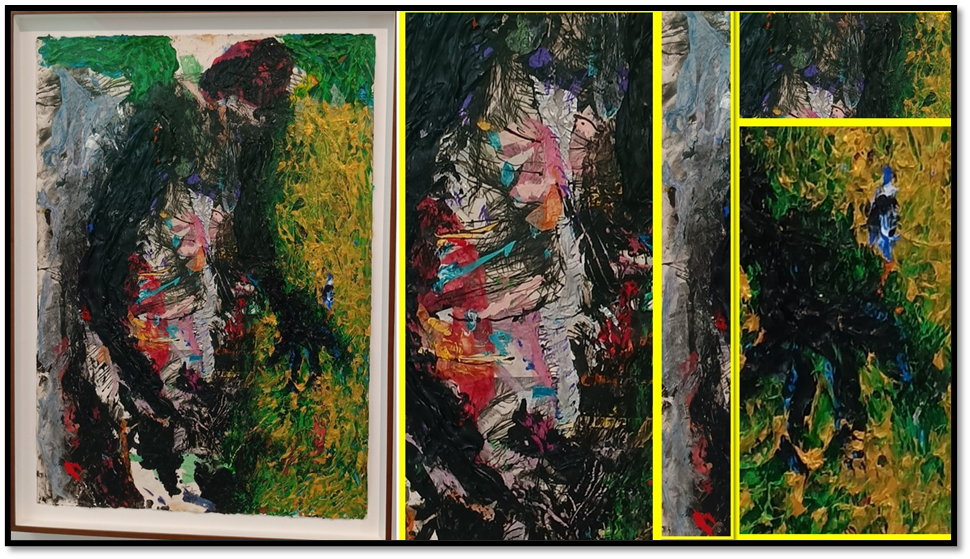

There is a brief preview video for the Hepworth show which I saw before coming on the gallery’s webpage on the exhibition and which whetted my appetite for a considerable painter (which I fully believe her to be). The USA artist Sylvia Snowden talks there of being a figurative painter obsessed by ‘impasto’ techniques – the use of layers of paint – sometime very thick that frequently overlap – and get bound up in the creation of character. I love viewing impasto work and to see Snowden’s pieces is to see it used with passion, together with the use of blank space to define the characters painted, however sloppy and overwhelming challenged by thick impasto their edges. Impasto is impressive to see because in it (think of Lucian Freud) you almost see the painting process itself – as a process of complicated entanglement of colour layering and the effect of scraping off and other erasure techniques.

There is no doubt that ‘entangled lives’ emerge strongly from entangled methods of representing the, that play too on distortions that are agentive from both inside and outside of persons. One could take forever in the analysis of colour in Snowden and still not have solved whether any painter can be resolved into a painter working primarily with colour or primarily with formal design. Leaving blank space for instance is not a method that Vasari would have treated as a method of painters whose practice worked by colore rather than primarily by disegno – he contrasted Titian and Raphael by use of this binary. Yet there is more to Snowden’s blank spaces than an addition or subtraction to impasto methodologies. It has a lo⁷t to say about absences in the life of contemporaries – things denied rather than things of which the character has no capacity for enjoying.

But even without blank spaces some of these figures can become too easily as they are seen by empathetic categorising vision than as people whose turmoil and contradiction needs empathy and understanding. Some of these figure are extremely complex and all the more difficult to enter as they morph into monsters from one of their features – here the hands and their shadows.

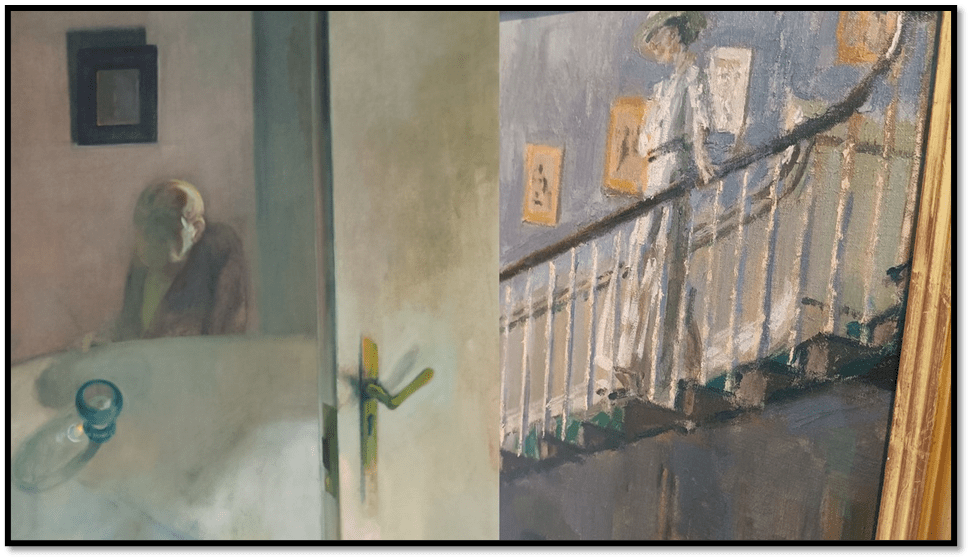

But impasto techniques are beautiful and meaningful in even more relatable and realistic figures in paintings that span both French impression and German expressionism. I do not know the artist of the painting detailed on the left but here the isolation of the old man seems captured expressionistically in the impression given of the absence of light or its variation, and the poignancy of messaging in the shadows falling on a door – shadows which might be stains. The man is faceless.

Both Catherine and I love Sickert since we saw him in a Liverpool Walker Gallery retrospective (see blog at this link). It was a delight to see a Sickert here neither of us had seen before where the impact of light from a huge window on a staircase makes everything about the figure descending the staircase numinous. Look in more detail below:

The effect of both motion and uncertainty is an effect of impasto that ‘derealises’ the vision in front of us. The foot descending the staircase is seen twice in front of sequential stair rails, the swirl of the printed dress too duplicates, the first swirl of the skirt of that dress, having behind it a gap through which we see the wall that ought to be behind the dress’s continuation upwards as its flow guides the body within it sown the stairs. It renders the figure not only full of motion but also a kind of queerness. Effects like this can only be achieved by layers of paint that do not pretend to show other than an appearance of things, but an appearance that yields no consistent impression and seems to express what is not otherwise expressible, something beyond ordinary perception.

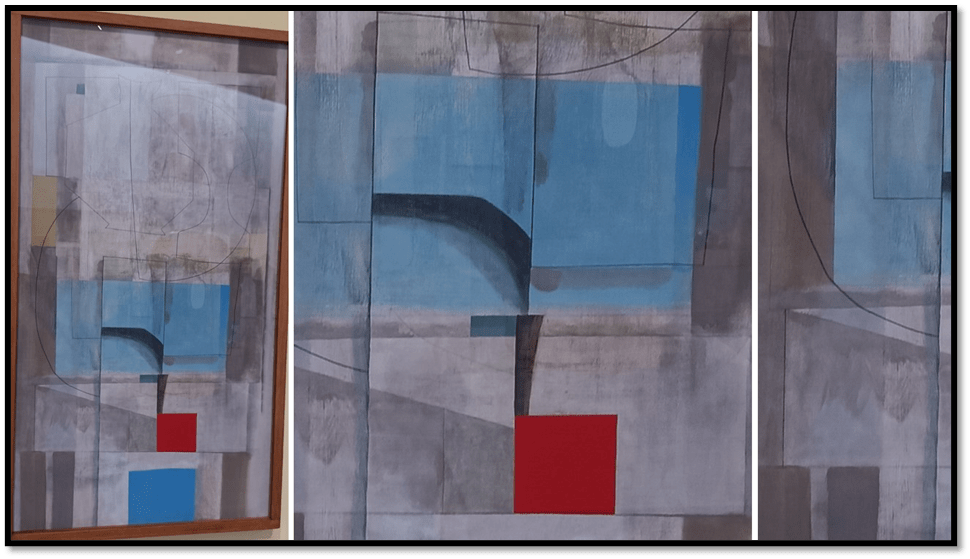

Of course the shift to abstract design in say Ben Nicholson may be the very opposite of all that, where it not that his abstracts are complicated by impasto too, as below:

We might want to see only blocks of non-communicating colour in fixed formal design but we don’t (though not using non-reflective glass for a picture like this almost ruins its nuance) . Shapes and colours ghost each other even in thin impasto like this, as details show, and straight or regular curved lines get queered being register by layering of shade, as well as colour.

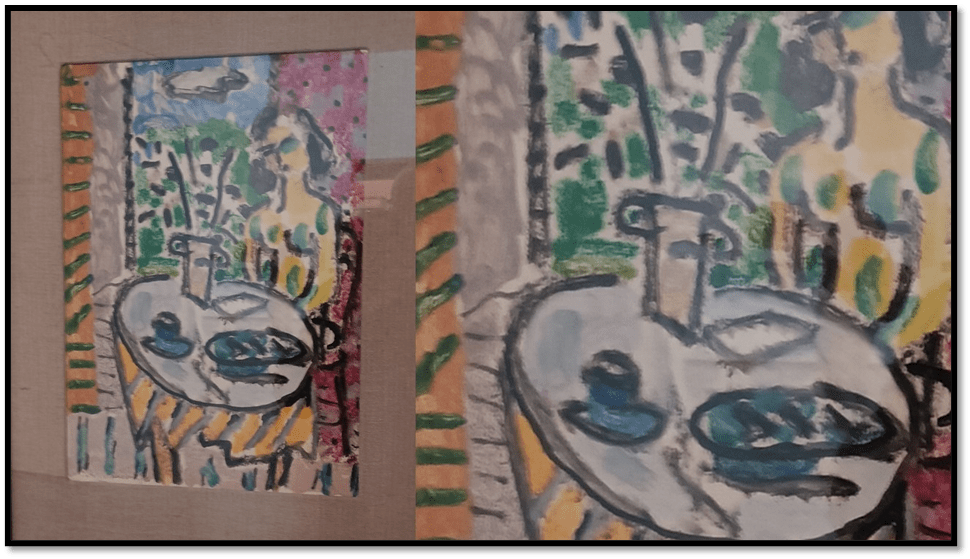

And near to Sickert was a Patrick Heron portrait, where design and colour are neither just a copy of complicated modern fabric patterns nor a device of a painter looking to abstract the reality we see but something in-between that constantly pulls us between illusions of depth and he certainty that all the linear patterns and colour blockings are merely surface effects – colours rhyming across the design without regard to reality, such as in the model’s facial delineation in a green that rhymes internally with an external view of what might be foliage or narrative mood.

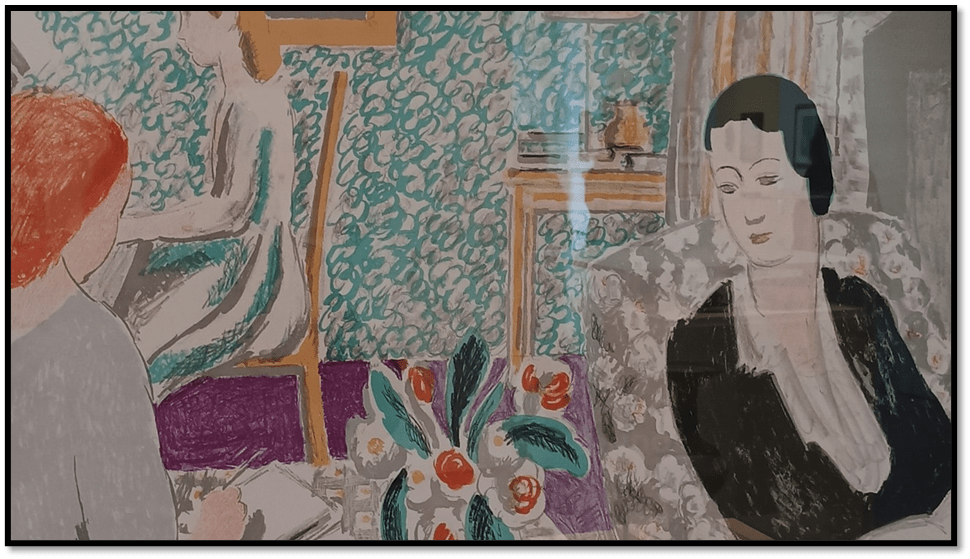

The master of all this is surely Vanessa Bell so it was a delight to see the holding from the Hepworth collection which I have seen in so many exhibitions.

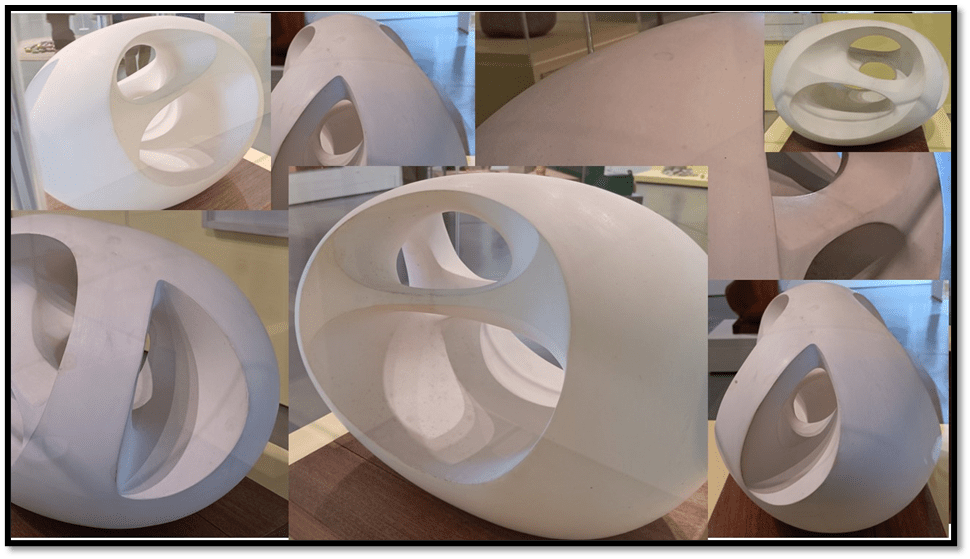

My passion for Hepworth knows no end so at first was delighted when Catherine asked what I saw in her work. But even by concentrating on one famous example alone got me nowhere. For I started to vary my perspective on it in ways that soon made me speechless. For from some angles and proximities we see what cannot exist, a pure relation of form and accidental contingent colour intruding into the basic material, impossible shapes even. As below:

All I could do was try to photograph perspectives and collage them, reproducing my vertigo and anxiety in front of art that must be as near as perfect as is possible – being neither abstract nor associated with real both – a picture of natural landscape and extreme artifice, space and solid matter at one moment of time with unclear boundaries.

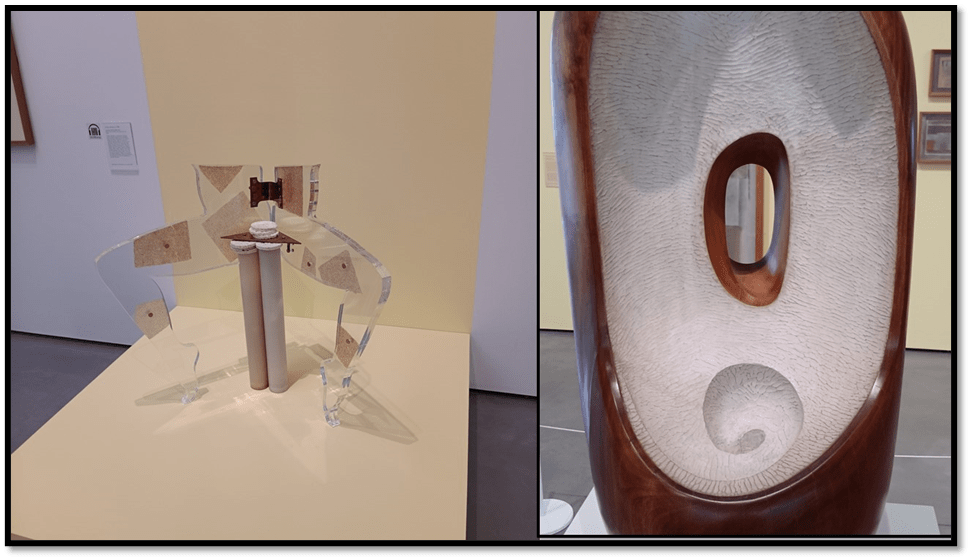

Since my next piece is on being unable to learn from seeing the work of Bharti Kher at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park main exhibition (and hence will be brief), I think my response might be summarised in comparing two pieces of sculpture I saw at the Hepworth.

Of course the comparison is unfair but it strikes me as a useful one between a conceptual feminist art (on the left of the collage) and that of a deep feminism like that of Barbara Hepworth. Both comment on the fascination with the vagina and vulva as an image of woman, but the story told in the wide-open Perspex legs is too obvious, the point detracting from any pretence at art. We are left with cleverness alone: a woman saying, ‘Thus I differ from men’, and it typecasts me, it subjects me to misunderstanding. In Hepworth the forms are more universal but no less feminine both as mathematical or natural suggestions of fractals. There is no origin nor end to that beautiful work. As a man it shames me that I think I might understand the genesis of womanhood as a simple cultural construct and not one requiring vast revolution and spirals of change in the world od selves, objects and processes. In this she resembles Ron Moddy, but more on this much later.

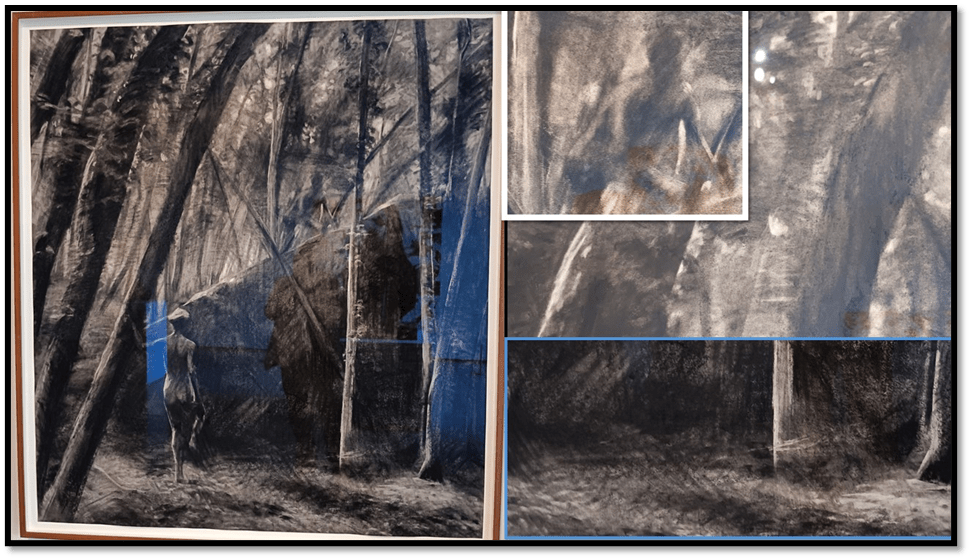

Most of this piece can be seen in the regular rotations of its stock in the Hepworth, but wherever you are in the cycle you won’t be disappointed. Nut I want to leave with an anecdote, Twi very charming Yorkshire ladies were looking at a fine drawing by the queer artist Jake Grewal (see below):

They assumed, and might be right, that it compared a female standing figure with a crawling male one on the top of the structure running diagonally through the picture. ‘It is a long time since I looked like that,’ said one to the other, and then caught my eye and laughed. ‘Me too’, I said nervously, being an overweight old man. The elder lady giggled and caught my arm: ‘I should hope you never did: she’s a girl’, and then moved on with more ripples of laughter. After they went I went on staring but by now the issue of sex/gender distinction was fixed into the picture conceptually, though not by solid evidence I think, though no doubt both biology and gender symbolism might be invoked. But surely the painting has done its job – what stands and what reclines? What is straight and what is bent, what rough and what is smooth, hard or soft? Aren’t all the mysteries of sex/gender/sexuality in these binaries that are not really binaries.

With all my love. Back with some disturbed thoughts about Bharti Kher at the Sculpture Park next.

Steven xxxxxxxx