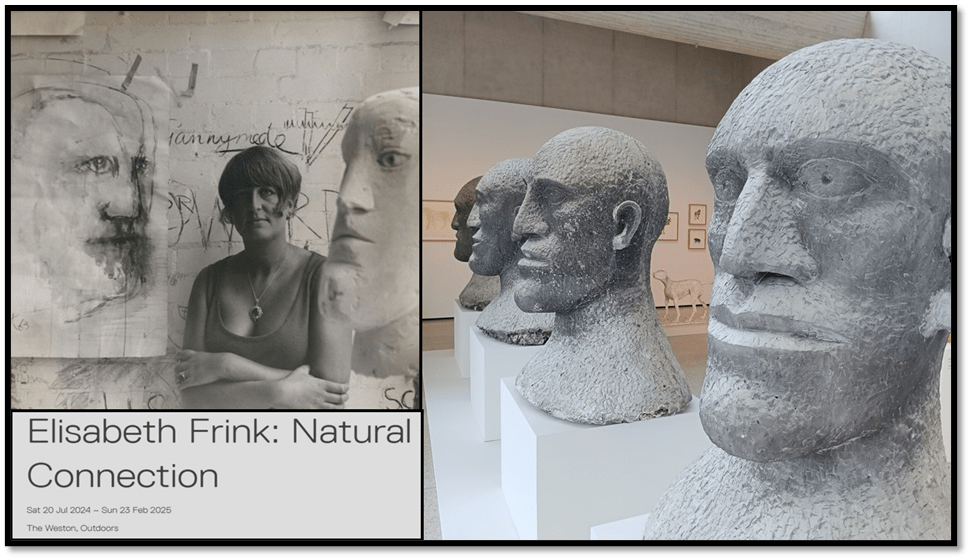

The Royal Society of Sculptors describes Elisabeth Frink’s ‘single-minded focus on the male form, the divine and animals, from which she never deviated’.[1] A look at a small exhibition celebrating The Yorkshire Sculpture Park’s being gifted 200 new works by Frink suggest, man, the divine and the animal are not mutually exclusive subjects. Blog 3 of 6.

I really have my friend Catherine to thank for ensuring that I saw this after a long day, where I was ready to give up viewing the art and drive back to Crook in County Durham. We were quite satisfied with our day so far, and I did not relish the walk to the Weston Gallery from the Chapel (see the footnote below for access to the blog about the sculptures by Leilah Babirye we saw there). [2]. Walking there would be fine, for it was downhill, but the long uphill climb back to the Main Car Park afterwards was a daunting prospect.

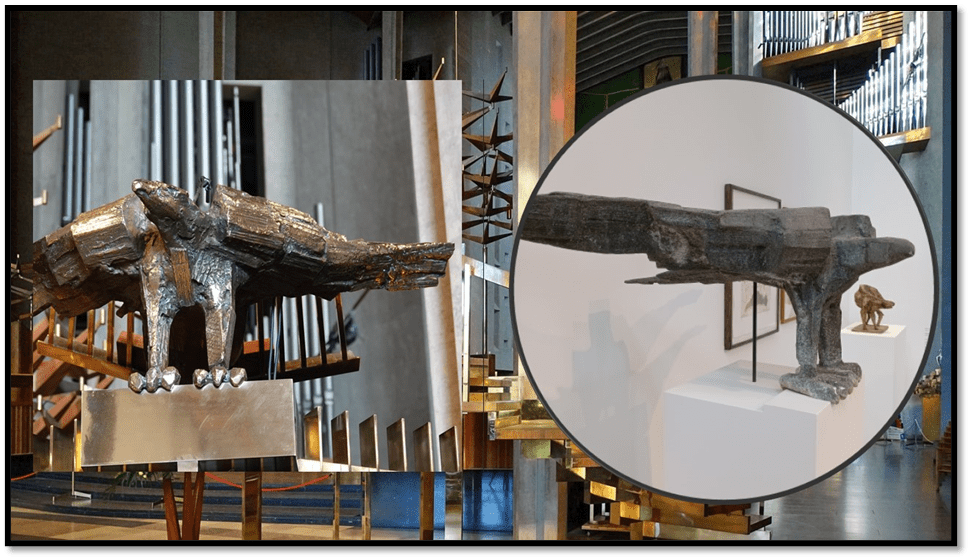

I have to do this blog to commemorate the enjoyment I felt in art about which I feel and am largely ignorant. Since seeing some of my errors I have ordered some reading on Elisabeth Frink to try and improve on current deficits, but that is for the future rather than this blog. I made mistakes with attribution and memory whilst there, including of episodic memory. For instance, I got mixed up about when I saw the Frink’s 1942 Eagle Lectern for that was from long ago when I visited it at the ‘new’ Cathedral in Coventry with Geoff when we both lived in Leicester with a Cathedral-associated trip to Liverpool where Catherine joined Geoff and me on our art jaunt. In that place I now concede the only Frink we surely saw was Frink’s last work, Risen Christ.

The entrance to Liverpool ‘Protestant’ multi-faith Cathedral.

Apologies then to Catherine because I remembered my error only when I got home and started this blog, remembering merely that we both had a history with Frink’s work (see this blog for an account of that trip). This error had its advantages for it fuelled my wish to see the Frink show, named Natural Connection, which had just opened at the Park, and Catherine being who she is, so helped to make that possible, working with the kindly lady overseeing the Chapel exhibition. Together they devised a plan to get the old man (me!) his wish.

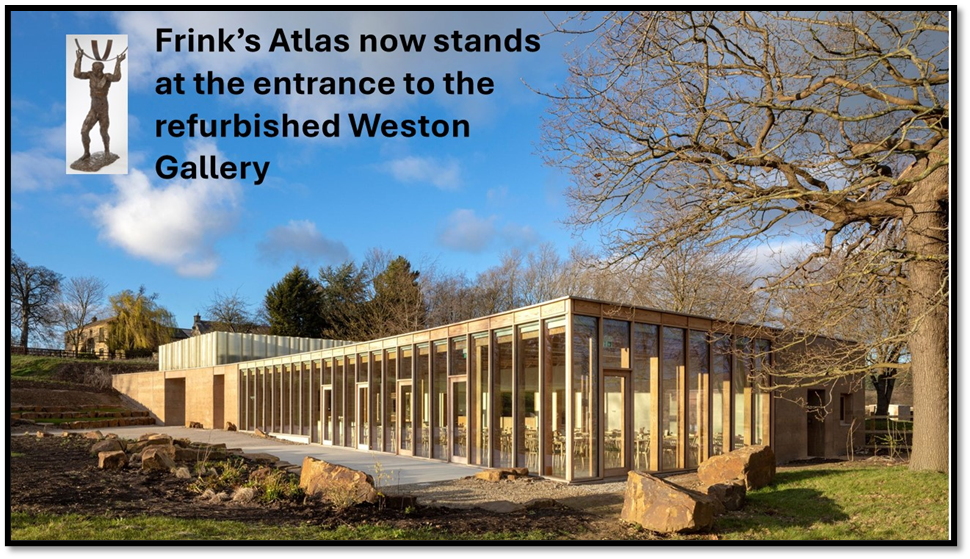

In that plan, Catherine and I would return to the car after leaving The Chapel, drive to The Weston’s own car park, which was on the way to the M1 anyway, and we’d see Natural Connection there, omitting though the finished Frink works in the grounds of the Sculpture Park, which would have involved additional walking between them. This would help, Catherine rationalised, with conservation of energy for me to drive from Bretton to Crook. And this is what we did. Indeed, the plan came into its own when I realised in the Weston Car Park how tired I truly was – missing the rather obvious signs to the Car Park entrance and instead approaching the Weston building by the back entrance, where now stood Frink’s Atlas figure, bearing a token of the curvature of the globe.

Another bonus It was good that we saw we could get a coffee (and hence caffeine) for the whole of the windowed building below is a café and shop, the exhibition filling only the enclosed part of the building above that in the picture below. We could, we saw, spend enough time in the exhibition, it being relatively confined in size, and then revitalise with caffeine. So into the exhibition we went.

The exhibition contained mainly maquettes of statues situated elsewhere, and not necessarily in the Park. Though it took its turn to be seen I could not but look for the Eagle Lectern throughout, seeing it being no disappointment, it being so closer to the eye for inspection that the liturgical bronze versions – that in Coventry being raised on a dais to be used only be clergy. To see the plaster maquette was more than satisfying. I hope my collage below shows that:

Background picture. Coventry, the site of the bronze lectern

Proximity seems invited with maquettes and their low emplacements, unlike the large figure maquettes at the Hepworth of works stunning in size even as maquettes, like the huge piece representing The Winged Figure (which we saw earlier that morning at the Hepworth Gallery), viewable otherwise only on the side of John Lewis’ department store in Oxford Street London. There is something more viscerally feral in the maquette eagle, as if in the act of pouncing on lost souls – even if only for their own good.

And eagles are a special bird for Frink I think, in the hierarchical bestiary I imagine existing in her mind. In my title I cite The Royal Society of Sculptors description of Elisabeth Frink’s ‘single-minded focus on the male form, the divine and animals, from which she never deviated’ [3]. Even there, though, I hinted that her bestiaries are somewhat symbolic rather than representations of merely natural. With birds, the eagle seems reserved for purposes nearer to her ability to capture the ‘divine’ in function and affect, by the affects associated with the divine mix with those of animals, and I think, as shall we see for her understanding of ‘man’, which is not an asexual or ungendered term for her. The eagle lectern. I have already spoken of the maquette eagle looking ‘as if in the act of pouncing on lost souls – even if only for their own good’, and there is that in her dainties and her men. I need to know more about Frink, though, before I test the validity of that feeling (I ordered the reading on Amazon today).

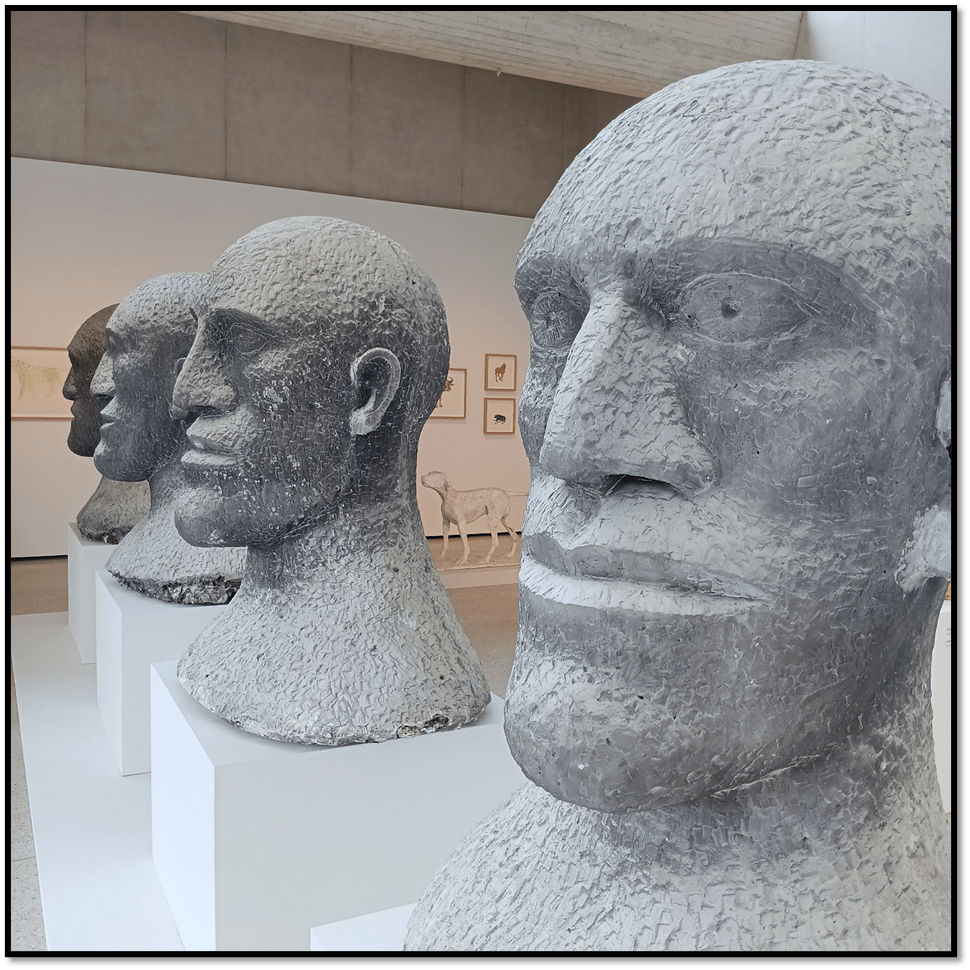

Frink specialised latterly on large heads of male models, some called ‘goggled heads’ that wear threatening dark glasses, barriers to any empathy you might feel in them. Even the large maquettes of what I think are his Heads of Virtue, the faces – huge and forbidding look down on you in shame (even when you stand next to them, with eyes that piece having no pity, given up to judgement, even in their silence.

There were some fine drawings on show and two in particular link the idea of males to predation and to the show of justice, blending animal natural energy with the energy they have in symbols and in ritual pre-Christian religions. Frink is described as feeling identified with a group of artists named after Herbert Read’s judgement that their focus was on the ‘geometry of fear’. Here is his fuller statement from a 1952 catalogue introduction, for though it is not by him directed at Frink, it feels like an influence to these drawings.

These new images belong to the iconography of despair, or of defiance; and the more innocent the artist, the more effectively he transmits the collective guilt. Here are images of flight, of ragged claws “scuttling across the floors of silent seas”, of excoriated flesh, frustrated sex, the geometry of fear.

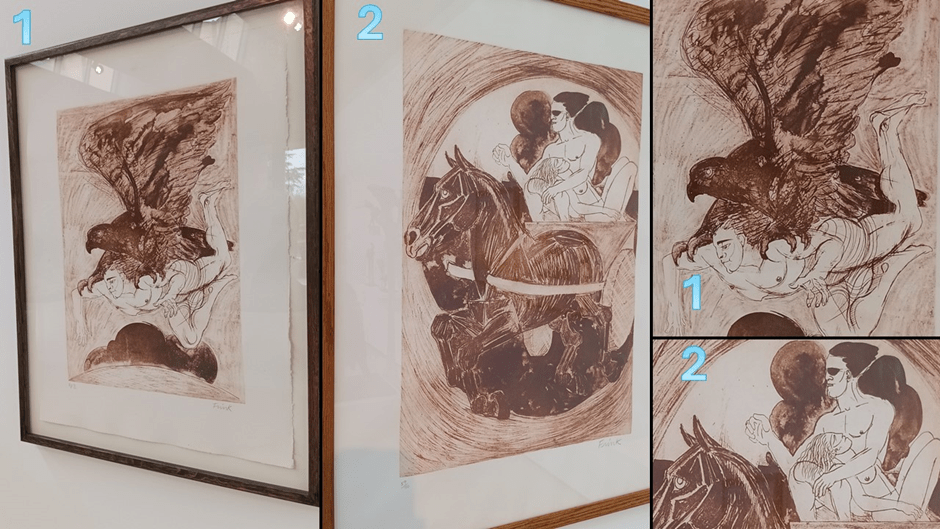

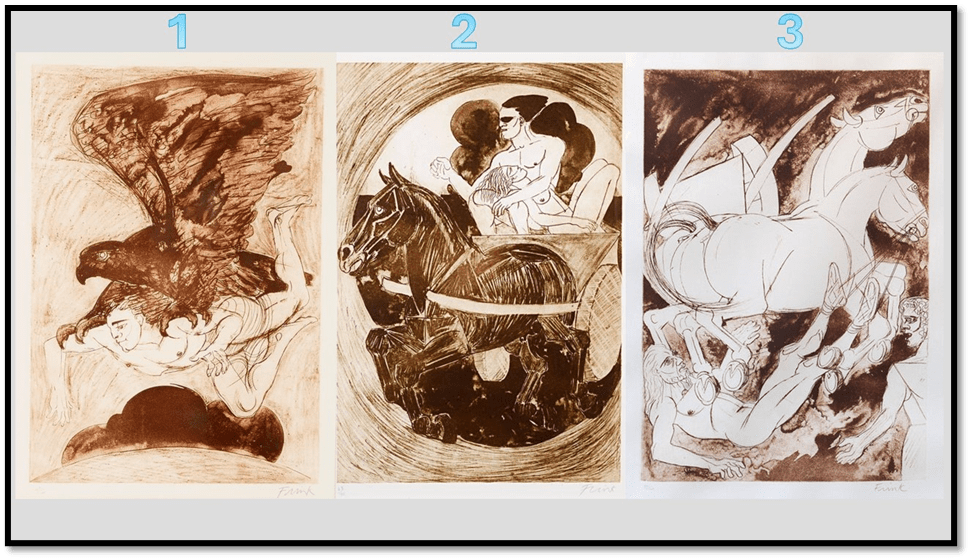

Rather than just a ‘geometry of fear’, I think it might be as fruitful to look in Frink as well for ‘the iconography of despair, or of defiance, ….collective guilt, flight, ragged claws “scuttling across the floors of silent seas”, of excoriated flesh, frustrated sex’. Perhaps, I think, strongly the latter though it is a frustration sometimes turned into severe projectile judgement that sees the worst that might lie inside itself in the other – whether as ‘sin’ in liturgical contexts in Coventry or people brought to judgements by a council of all-seeing Gods, who see more than the judged know of their guilt. Here anyway are the two drawings, the first labelled The Rape of Ganymede (no 1 below) in the exhibition and the second I read as being the wrongly labelled Laos and Oedipus but which is in fact Hades and Persephone (no. 2 below). I did not see the true Oedipus and Laos. It may have been there and I misread the labels (as I said I was exhausted).

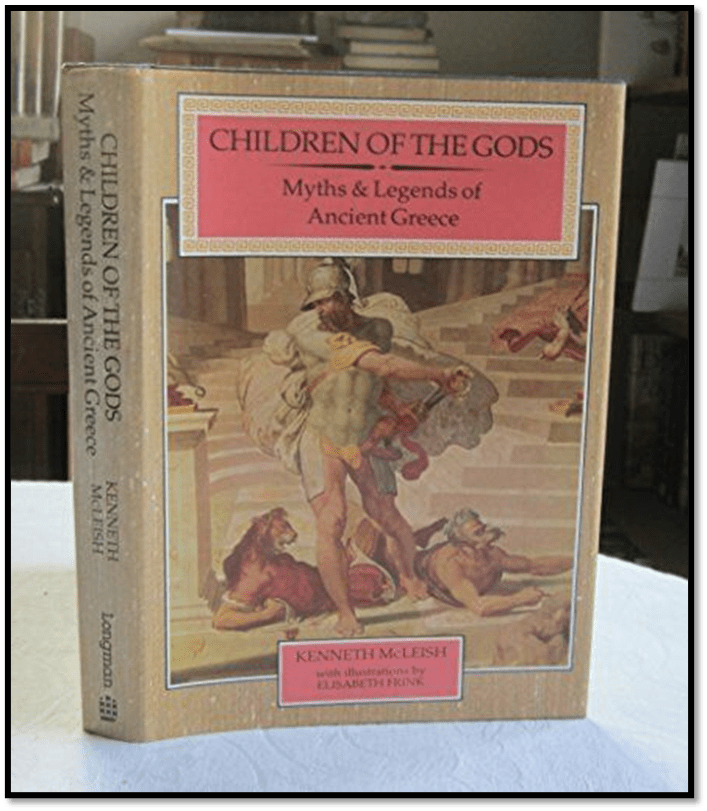

All three drawings are sketches in fact from the same series of illustrations (see pictured book), The Children of the Gods. Here is the book:

The one I label number 2 above and below is in fact, as I say, Hades and Persephone (hence the ‘goggled head’ of that Satanic force driving his chariot). He carries a woman in his arms, though the head is rather ‘masculine’, within the chariot not his son Oedipus, though Laos bore the stigma of having raped the son of his host Pelops, the abducted Chrysippus, in Greek myth, though I thought this might be a reference here I was carried away with the misreading of the label. The true Oedipus and Laos is no. 3 below, taken from an internet reproduction:

Again it was only when I got my notes and photographs home I noticed this error (my own or, improbably theirs – though I wrote on Twitter to check (as below).

No matter the truth, these pictures elide the mythical, symbolic or allegoric of the animal, the masculine (for woman get not a look in, even Persephone apart from the breasts having a manly look). Frinks Ganymede is a highly developed youth, soaring as if part of the rape in progress of him by the hierarchical apex of the birds, Zeus in the body of an eagle. In both others the energy of horses is complicit in male rape or male wish fulfilment to reach the apex of power, as Laos’ chariot horses trample the thrown father as his son, Oedipus looks on. These drawings in the flesh show the energy of Frinks art – even two-dimensional but its of a divine and an animal conflated in the male whose power terrifies and threatens. And so does the eagle lectern.

This is surely the case with her anthropomorphic birds, who stand and walk like vengeful predatory male gods – less anthropomorphic as hybrid men-beasts. Awaiting prey or resting till ready for it, Frink gets toxic masculinity but seems so in awe of it that she accepts its superiority. Here again, I need to see and read more of and about her.

In her horses there is more a case for the latent energy being more naturalistic. I particularly loved the horses sculpted in a moment of rolling on the ground, though Catherine thought them sinister (maybe she is right). The aim after all is for Frink, if not for horses per se, to display the bulk of powerful muscle that though in innocent play is compounded of threatening danger as in the Laos and Hades examples.

And I could not leave until I examined again the polished stone pieces which seem a mineral compound of animal, divine and something of the divine predatory male. I need to think more about those. This exhibition had used the last of mu energy to see.

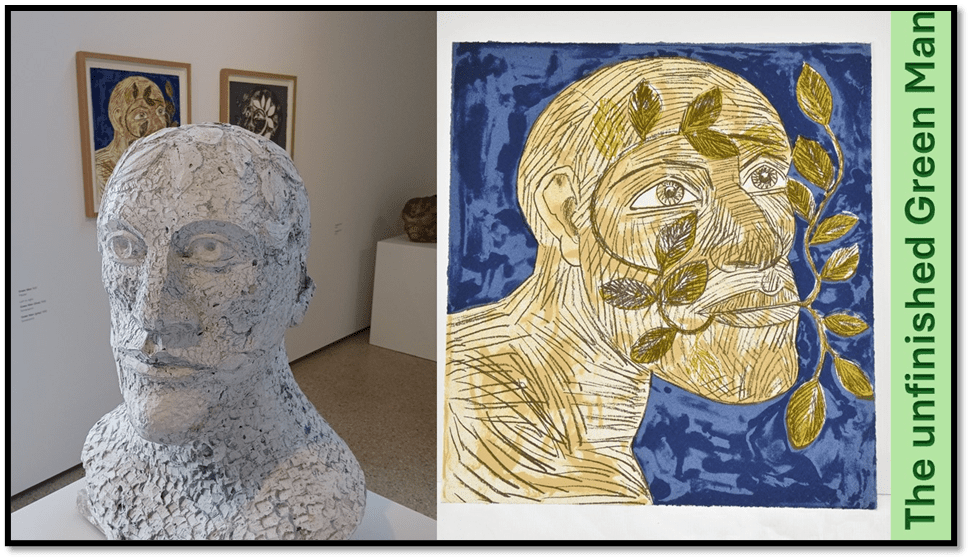

did learn that Frink died before finishing her last piece to divine male heads compounded of the natural – her Green man, but here were a powerful painted sketch and a maquette of a wreathed head – almost Apollo as the more earthy sub-god that is the Green Man. I could have gazed on.

But please do not worry about Catherine’s safety, She took me to the café. Bought me a strong cappuccino and an heroically proportioned cheese scone (delicious by the way from lovely friendly Weston staff) and I set off for the MI, able and capable for the drive to Crook, but for missing the A1 turning on the roundabout on first try – well, anyone can make mistakes. Lol.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] https://sculptors.org.uk/past-members/elisabeth-frink

[2]

This blog on the queer sculptures of Leilah Babirye is from a series of blogs on a day visit to see art in Yorkshire exhibitions: here at ‘The Yorkshire Sculpture Park’. This is number 2 of ?.

3 thoughts on “A look at a small exhibition celebrating The Yorkshire Sculpture Park’s being gifted 200 new works by Elisabeth Frink suggests, ‘man, the divine and the animal’ are not mutually exclusive subjects. My Yorkshire art day-trip – Blog 3 of 6”