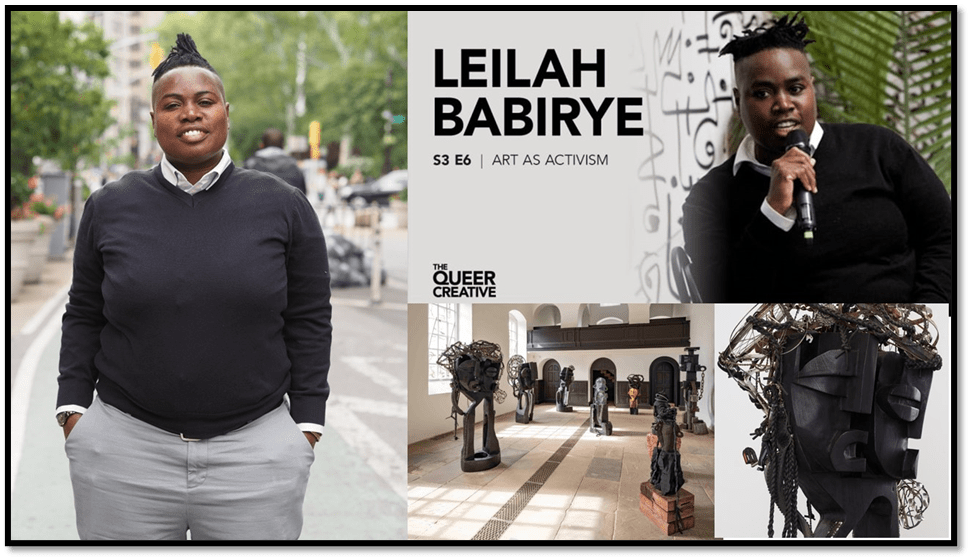

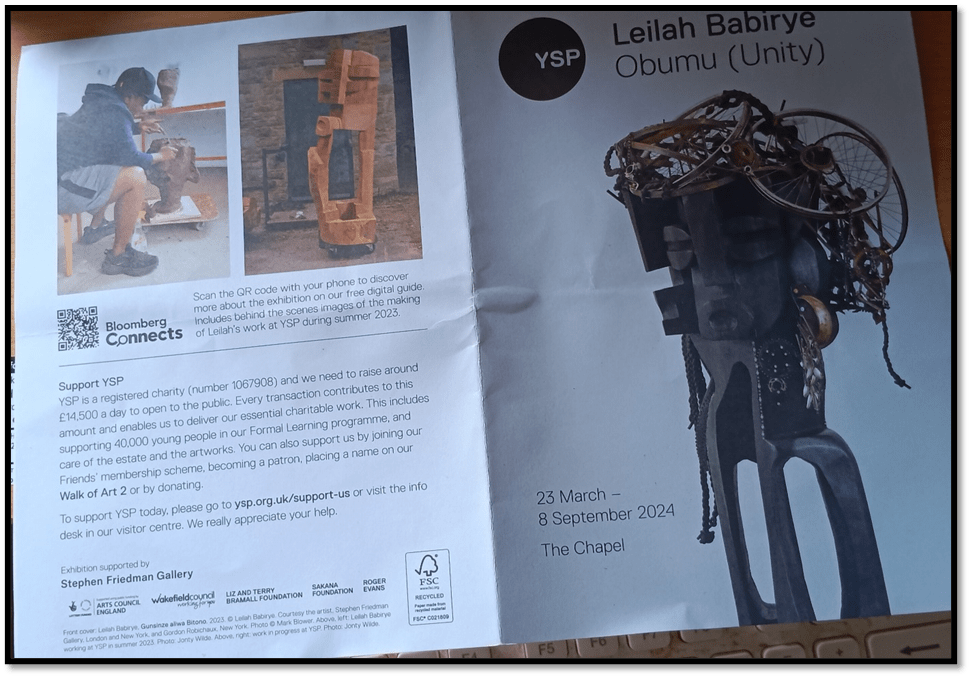

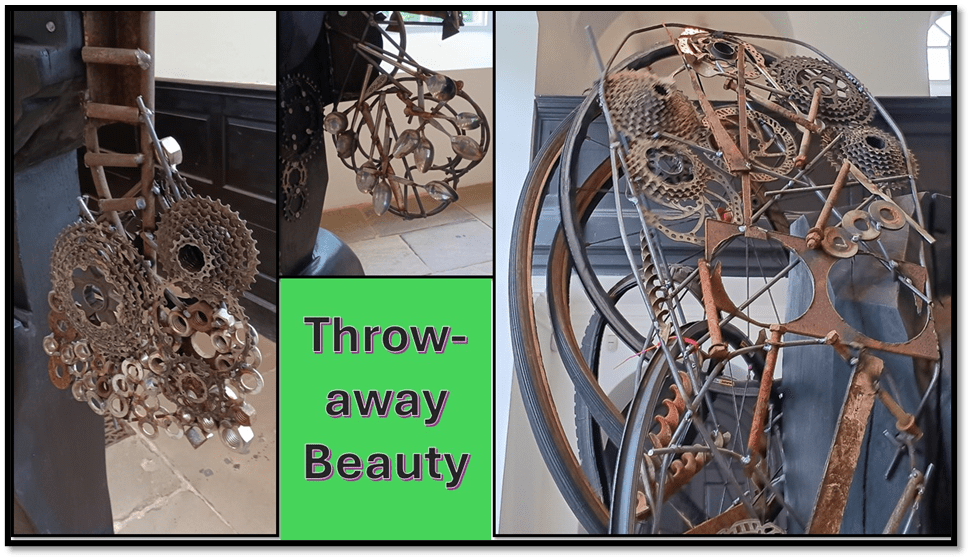

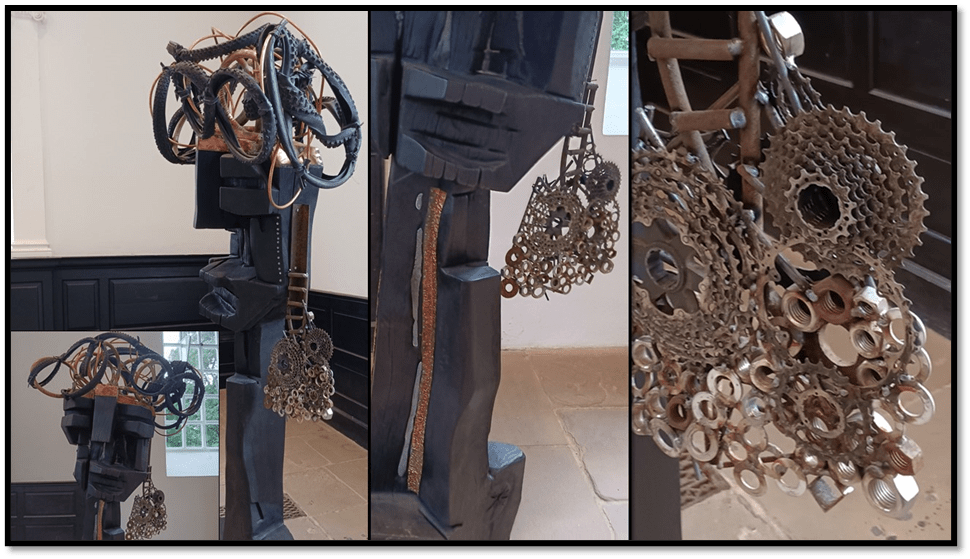

Leilah Babirye, showing some of her work currently in The Chapel at Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP) is creating an art of resistance from her experience of growing up queer in Uganda. She uses ‘items found on the streets, such as tyres, cans, and scrap metals’ in the words of Melis Dumlu. Dumlu goes on to say this practice ‘echoes the prejudiced slang for a gay person in the Ugandan language – “abasiyazi” – which is a section of the sugarcane husk that is removed as rubbish and thrown out’.[1] This blog on the sculpted art of Leilah Babirye is from a series of blogs on a day visit to see the art in exhibitions at the Hepworth in Wakefield and The Yorkshire Sculpture Park at Bretton Hall Country Park. This is number 2 of 6.

The story of Leilah Babirye’s experience as a queer artist and woman is told well in The Wikipedia account of her (use this link). Yet part of that story is not told in her account of her life in an interview with Helen Phelby, published as a leaflet available at the exhibition. She tells us that she left Makere University for the USA and a Fire Island residency as if there were no politics involved. Here are the details as told in the Wikipedia account.

In 2015, Babirye was publicly outed in Uganda’s press, was denied supervision from her tutors during her Master’s at Makerere University due to her sexuality, and was disowned from her family. These events led Babirye to apply to artist residencies in the United Kingdom, Sweden, and the United States, the latter accepting her application for a residency in Fire Island, a popular gay destination in New York’s Long Island.[2]

There are good reasons that queer people resist telling stories of rejection by their families, and in this case, from the receipt of education and the right to represent her nation as one ifs artists. Victim stories fail us in the end, for the imply identifications of ourself we must resist in order to live a life that we can ourselves value. Maybe too many of us have been forced down a road where our value is negated, where as it were the last one to reject the life that makes us a person capable of giving, receiving and valuing love, through all the ranges in which that is possible, is ourselves. To know oneself as a victim and a failure in the world, as an outcast, is the best way of ensuring that everything we are and could be, everything we do and could do, is rejected so finally that even we hate ourselves and beat ourselves

In that leaflet, rather than tell stories of past rejection, Babirye tells of being ‘an activist for the LGBTQ+ community back home and now all over the world through my art’. Her art is a form not of registering the experience of having value subtracted from your experience but instead assigning it to herself and others in those communities of commonality in ways that multiply it infinitely. If biological families reject you, do not chosen families welcome you and embrace you, both as your collaborators (for hers is a collaborative art first and foremost) and those who find in your art a source of dialogic self-development.

Even the works themselves are assigned family status through naming, as one names children, or even animal family members (and each has artwork has an animal name, as is the custom of name-giving in the sub-kingdom of Buganda, from which Babirye derives. If each artwork, a character after all, an individual name, the whole family is called Obumu (Unity). Babirye says: ‘I assign our family names to my sculptures, so that we can live on forever’. The most important experience that she wishes visitors to the exhibition to have is to: ‘Feel the teamwork’, for there ‘family’ in the making of art and the creating of communal value too. The team at YSP unlike Makere University made her feel ‘she was in college for six weeks’, but in a college of mutual learning and ‘too much fun’, not the patronage of learning academies. And how do families help each other: precisely in ways that Leilah’s failed her. They, as she does her ‘audience’ help them ‘to rethink things like gender and sexuality’. This involves sometimes assumptions about the labelling of sex/gender categories for Leilah says that ‘sometimes people reach out to me and question why I use a “male name” for a “female looking” sculpture or a “female name” for a “male looking” sculpture’. [3]

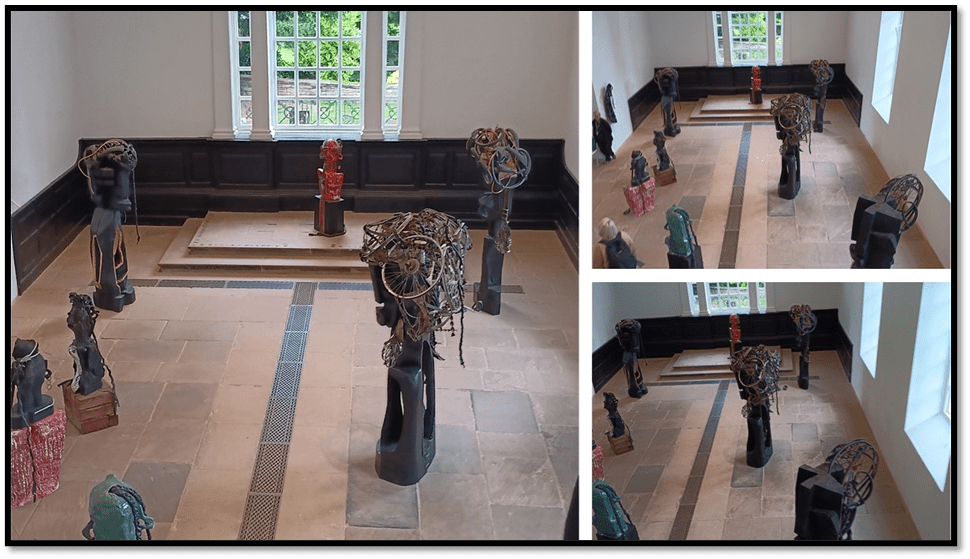

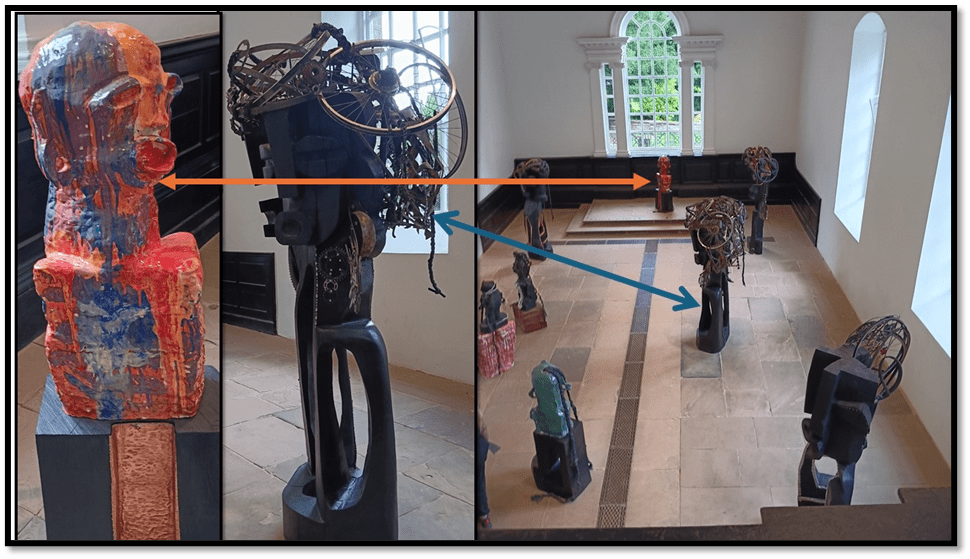

And the exhibition is housed in a new exhibition space, once the Chapel of Bretton Hall, a teacher training institute when I lived in West Yorkshire, and a place of quiet reflection. On approach, it has the look of an Italianate palatial home.

Inside, the pieces stand apart but somehow bound together in their differences, some clearly talking to themselves or each other. They possibly use each other’s names.

I took those pictures from the choir gallery which I visited with my ear friend Catherine, who may catch in some of the other collaged pictures below. As we did rom that gallery, if you allow your eye to flash across the pieces (even the two-dimensional ones in my collaged photographs) they seem to move toward each other or away from each other. Like all communities sometimes their differences make them selective at times about whom they can approach best, and who should be avoided for now.

I won’t be naming these artworks or their characters however, for I took no notes of individual names (another reason for me to return). However their names are clearly important so look out for them if you go. They are in fact named by the clans such as those that exist in the older Bantu kingdom of Buganda (now part of Uganda).

Each sculpture in the show is given a name from a different clan. This includes Kuchu Nte (Cow), Nyange (Egret) and Kuchu Nsenene (Grasshopper) clans. This is to represent queer Ugandans that exist in every clan.[4]

The best piece of writing I came across was online in the website ‘Artists Responding To …’ and was by Melis Dumlu. I cite Dumlu in my title, for their theme is the use of rejected materials (trash, garbage or rubbish in various English-speaking cultures) in order to make new art. Dumlu makes the point that this alone shows how the art relates to the symbolic resurrection of coming out and living as a queer person, in any culture. Her quotation in full is as follows:

Her sculptures often include items found on the streets, such as tyres, cans, and scrap metals, which echoes the prejudiced slang for a gay person in the Luganda language – “abasiyazi” – which is a section of the sugarcane husk that is removed as rubbish and thrown out. This choice of materials is both symbolic and practical. Her sculptures are not just visual statements but acts of defiance and reclamation.

Later in the piece, the issue is spelled out more fully, when Dumlu says that Babirye’s:

… totem-inspired sculptures delve into the essence of identity, illustrating how the Ugandan Queer community perseveres whilst imagining and creating clans despite societal rejection. Babirye was raised in Kampala, situated in Buganda, a powerful kingdom in Uganda. There are at least 50 recognised clans within the kingdom, and Babirye reimagines her culture and heritage by creating her own community of Queer Buganda clanspeople.[5]

What is reinvented then is not only a once-proud pre-colonial Bugandan tradition, for most accounts show that homophobia was a colonial import, as were homophobic laws and a virulently homophobic Church of England in Africa, often directed at traditions of cross-dressing in early African clan experience associated with high value persons like shamans. Babirye is reinventing a new tradition but based on traditional craft expressions of spiritual value: ‘Babirye creates ceramic heads adorned with traditions like mask making and elaborate crowns, symbolising the enduring pride of her people’. Queer pride hence becomes something of national and communal pride derived from materials own ‘thrown-away’ and rejected but re-envisioned as ceremonial regalia. Let’s honour this recycling of value, what I call in the collage below: ‘Throw-away Beauty’.

This was a flying visit, of course, but that can be joyful even in the fact that much gets unnoticed. I think I missed some of the individualisation of the pieces, though it was evident. But other more fanciful projections get entertained in looking at the art, like, for instance, how relationships of ‘unity’ are captured, even in imagined queer communities or ‘clans’. In the ‘inter-relationship’ of characters. Hence, what I saw or imagined made me think that the curation of this show was as canny about the use of exhibition space, including empty exhibitions space, as was that in the Igshaan Adams exhibition at the Hepworth (for that blog follow this link). Look for instance at the collage below, where the placing of each identified individual piece is shown as it is positioned in the chapel space by orange and blue arrows respectively.

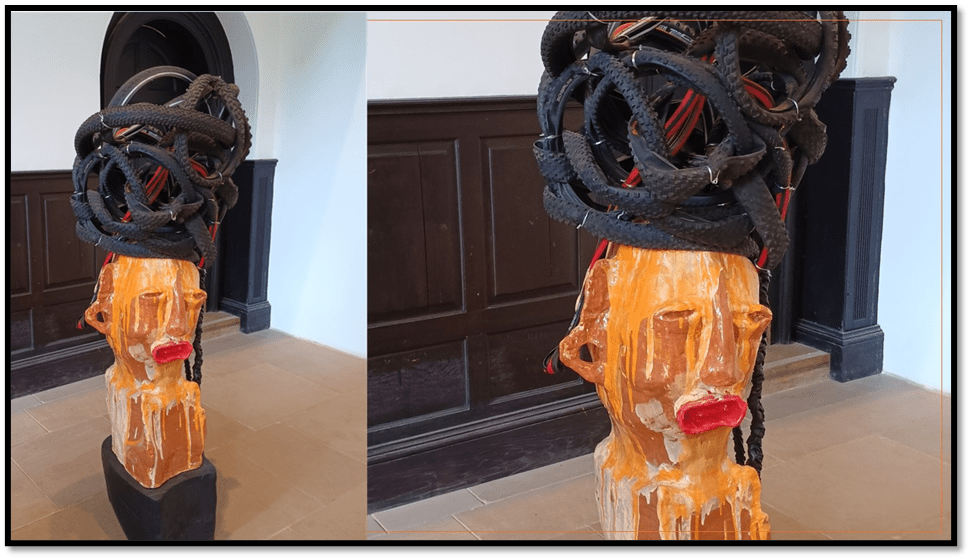

The multi-coloured ceramic character with the bold mouth, used to shouting or singing AT others with authority lips and rather over-observant eyes, accustomed to surveillance, is facing slightly to the right of the chapel nave. He, she or they stand on the altar-stage looking right out at the bustle amongst the tallest of the chapel congregation, finessed and standing taller than their height by virtue of showing headpieces. Notice however the angled position of the character (indicated by a blue arrow) on the right of the nave, with a face that, though somewhat prepared (for they look slightly to the ground) to challenge the ruling of the bust in charge. As I think all this fanciful stuff, even now I want to go again to see this show and check out sightlines between pieces that I had not even thought worth thinking about in this way whilst there.

However, I do not think the bust on the altar-stage challenged. Their headpiece seems even more symbolically crucial if less showy but difficult to interpret outside folklore contexts that may be real or invented in either case. Look more closely at that ceramic bust below with closer perspective. It wears a single pigtail headpiece, tied in plaits and then knotted to the back of the head. He, she or they , wears their colour on their surface as we have already noticed, alternating between attempts at cooler blues that erupt too often into passionate red. They may, as I said, from the open mouth, blood-red with passion, be singing quite extrovertly. After all, they have placed themselves (been placed I know but let’s enjoy social play casting whilst we can) where they have on the central altar dais in order to be looking out to the entire room if they wish, though they have chosen those figures with more apparent social and bodily status.

Compare them with other ceramic heads for Babirye says that work in clay is more demanding for: ‘With ceramics, the clay controls me’, whereas with ‘wood I can control myself’. Babirye has a point, for one can see by her output that: ‘Clay is so commanding’. Bur even then she modifies that view for if ‘commanding’ she has ‘with this material leaned to be patient’. And to be patient is ‘relaxing’, quite unlike hacking at wood with a chainsaw. And patience turns what is commanding into something that wears beauty not so much with authority but tempered emotion. The orange-yellow bust below has a plaintive mouth and perhaps cries sincere tears, if that flow from the eyes represents that without loss of commanding majesty.

Meanwhile a bottle-green ceramic mask, with two long pigtails plaited but not knotted, as a personality so subterranean or sub-aqueous (for a fish is suggested) its blue mouth tells stories that might just be oracles. These characters really do seem to live and resist being entirely subjected to our interpretations.

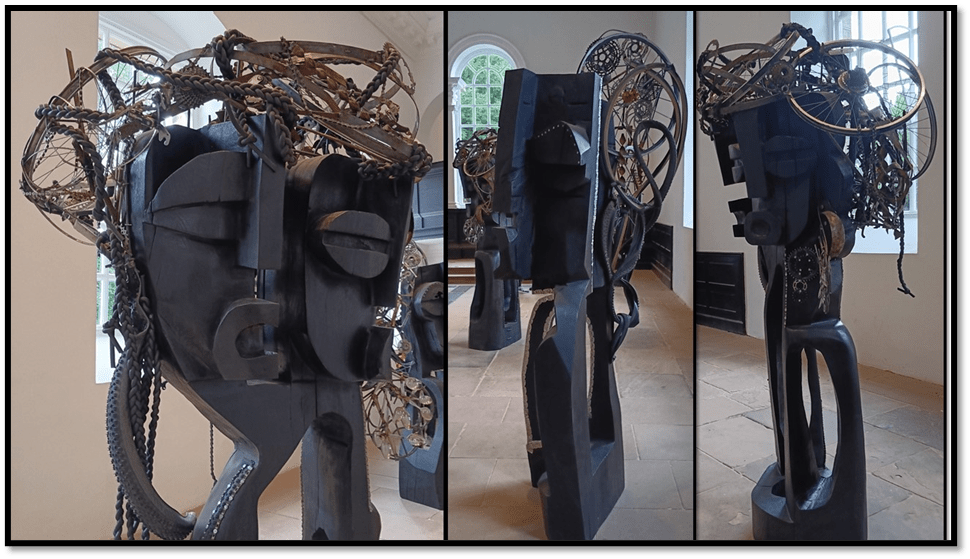

The wooden faces never get so fearsome, I think. One character has a face made up in the manner of cubist painting, with a face and eye that shift direction as they look at you, for the face is doubled. This is not the picture of a person ‘two-faced’ (by which Northern Occidental cultures typify hypocrisy and lying – for these cultures are too remote from the ‘mask’ as a tradition in their living culture – but of a face so mobile, it shifts its focus as you look at . The hair is not a piece for in some cases it is ragged and broken. The character of the hair pieces as we see in the collage is very varied, perhaps less controlled, less commanding of itself or us, more willing to allow emotion to surface of itself.

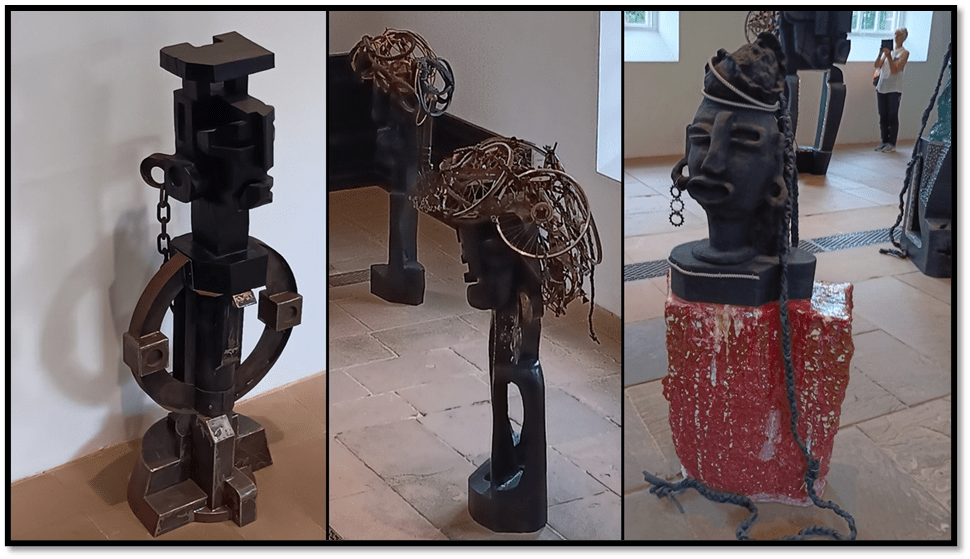

These figures differ so. One I got a sense of as a whole only by capturing its image from the balcony and enlarging it. This character has a body made up of geometrical fragments and overlooks other, pressed against the wall at the back of the chapel, almost under the shadow of the gallery. It seems to be contained by a regular geometry, especial by the circle that makes up its body, but is then let down by failures in being truly symmetrical in its more cube-like features which are stepped at different levels, especially at its base.

No fancy hair piece here, this character prides itself on its integrity, on the show of boundaries. Compare them to the tall figures at the front, already mentioned but also to the sensual character bust, who wears the same two-link chain ear-piece on the left ear, whose curvatures are the very opposite of the first figure I mentioned in relation to this collage. It is at this point where questions of sex/gender might be raised. Burt can they be answered? I think not because the sex-markers are mixed, as indeed they are in all of us, except in the statistical norms and cover a range usually for each marker not a gross measure of sex/gender.

But, as we end, let’s return to the re-evaluation of the rejected, of the social trash out of which these sculptures are re-formed in the aim of a general re-evaluation of persons. The appendages on the piece below may indicate an elaborate outer decoration of the self but in its cogs and gears also indicates how what is internal, such as the drives and shifts of cognitive and affective process entirely make up the stories of what human beings value in each other. The better when it is, as it rarely is, exposed to social view as something integral in itself. For the turning of emotional wheels and the motion of dynamic chains ought to make us see each other better and hide less. For masks, as is clear in Greek classical theatre, aren’t always about hiding emotion as seeing, hearing and bearing it with and for each other.

I do recognise that this piece is so subjective, it would be dismissed by art historians and professional critics, not that they will read it for it has no qualifications attached, but bear with me if you have got so far. For the purpose is to encourage you to see this show. It is so good! As queer art it is beyond explication (by me at least). All I know is that it is the art of a potential future for us, because it is serious about the unity in diversity we must also seek in the covered up past.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Melis Dumlu (2024) ‘Review of Leilah Babirye: Obumu (Unity)’ in Artists Responding To… (July 11, 2024)Available at: https://www.artistsrespondingto.co.uk/post/review-of-leilah-babirye-obumu-unity

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leilah_Babirye

[3] Helen Phelby & Leilah Babirye (2024) Leilah Babirye: Obumu (Unity) 23 March – 8 September 2024, The Chapel Bretton, Yorkshire Sculpture Park publication

[4] Ibid.

[5] Melis Dumlu (2024) ‘Review of Leilah Babirye: Obumu (Unity)’ in Artists Responding To… (July 11, 2024)Available at: https://www.artistsrespondingto.co.uk/post/review-of-leilah-babirye-obumu-unity

3 thoughts on “This blog on the queer sculptures of Leilah Babirye is from a series of blogs on a day visit to see art in Yorkshire exhibitions: here at ‘The Yorkshire Sculpture Park’. This is number 2 of 6.”