Should queer readers be interested in the queer coding of the recent past: The case of anticipating watching Noël Coward’s Present Laughter.

The blog written after seeing this production is available now here:

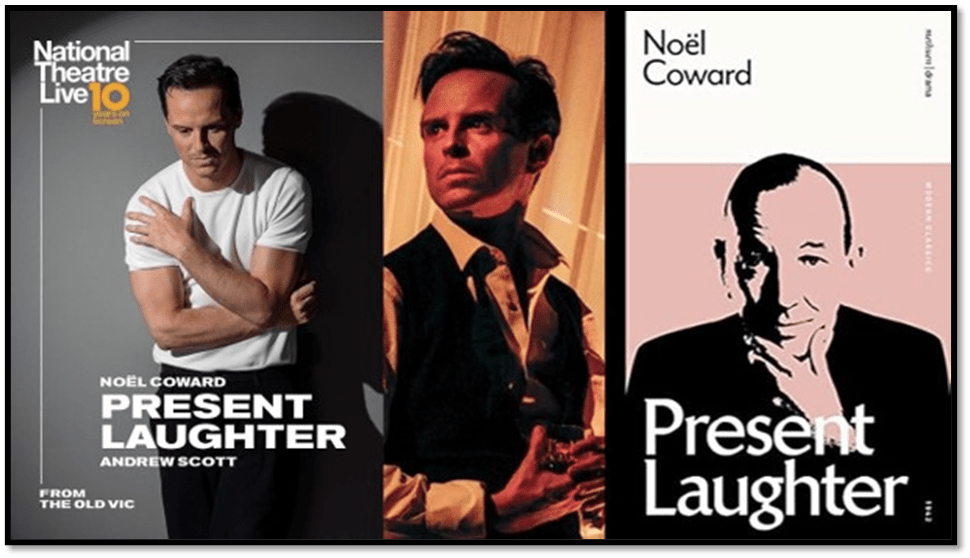

Next Tuesday, I will be going to see the re-streaming of a once live performance of Noël Coward’s Present Laughter with the extremely wonderful Andrew Scott playing the role of Gary Essendine, once played by Coward himself. The play was described by him according to Russel Jackson as ‘not so much a play as a series of autobiographical pyrotechnics’.[1] The point is all, it seems, in the acting as Garry says himself to Daphne Stillington. Daphne is a young woman who falls in love with him (as so many do in the play) as she sees him on the stage, and returns to his flat, to be put into the unheated and ice-cold guest room. That happens before the play opens but must be at some point that may or may not imply the occurrence of any sexual interaction beforehand.

Daphne: … It was the real you last night, you weren’t on the stage – you weren’t acting –

Garry: I’m always acting – watching myself go by – that’s what’s horrible – I see myself all the time eating, drinking, loving, suffering – sometimes I think I’m going mad –

Daphne: … I could help you if only you’d let me.

Garry: (rising and striding about the room) If only you could, but it’s too late – [2]

How does an ‘actor’ play such lines and enact such stage directions. We must, I suppose, feel them carried off by Garry so that they leave a sense, that convinces Daphne at least, that ‘poor’ Garry is trapped in an escapable role that he must continue now to play. But trapped by what? Is it by the repetition of actions so constant that they turn into habitual ones or by some more or less consciously adopted mask that plays along with social norms and expectations?

The stage directions are even written with conscious irony to show that Garry sometimes either likes or can’t help but deceive himself as well as others by the role he plays. Look for instance at how Coward gets Garry to send Daphne back into the ice-cold guest room – his performance so exquisite he allows it to linger on otherwise empty space of his London studio. It is empty space except for the naive Daphne, were it not, of course, that that space was actually a stage with both characters watched by a real live audience.

Daphne’s ‘uncertainty’ will be for the audience more of a certainty that Garry is enacting his role as ‘prey’ to emotion. He is prey – but only to being disturbed by how others want to see him and convince him that he is in fact, whatever he thinks himself to be, just and only the person who is as they see him: ‘Everybody worships me, it’s nauseating’, as he says soon after.[3]

He gently disentangles her from him and goes sadly to the window, obviously a prey to emotion, with his back to her. She looks at him uncertainly for a moment and then goes weeping into the bedroom and shuts the door.[4]

Obviously, for queer readers not bound by anti-queer laws and ethical proscriptions and the degree of social control of the appearance of other than heteronormative actions, thoughts and feelings (as was the case when the play was written and originally performed), Coward seems in all this to be encoding in his writing the entrapped nature of repressed queerness. The treatment of Daphne is in fact replicated with the hapless and devoted Roland Maule – who also falls in love with Garry’s passionless but forceful (in the manner of passion itself) social intelligence (real or otherwise). He will, at the end of the play, be left in the same ice-cold guest room, never to be heard from or seen again, as the curtain falls abd Garry voluntarily returns to a sexless but heteronormative marriage of convenience with his ex-but-not-divorced-wife, Liz, presumably leaving Roland locked into his London home.

Roland is the butt of humour, as much as is the naive young Daphne, but he is treated with less respect for the validity of his emotion. Garry is going on tour to Africa in the next days, and Roland says: ‘Would you see me if I came to Africa too?’. To this, Garry replies: ‘I really think you’d be happier in Uckfield’. Lower middle-class Uckfield (as in the Francis Frith photograph excerpted below) probably represents the heteronormal trap that Coward escaped by virtue of status, money and association with the ruling class, for queer lives had a public sense in that exclusive island of ‘privacy’ (punctured as it sometimes was by visits of that class to venues where might be found working-class men for sex.

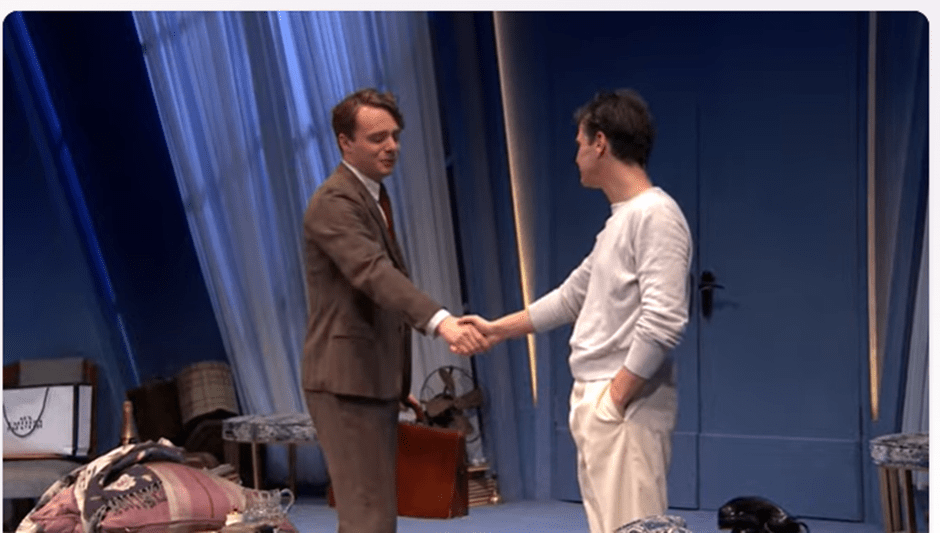

In the trailer I saw for the production I will see in full soon, Roland Maule’s is paying his first visit to Garry to get his verdict on his ‘play of ideas’ (Coward is satirising the writers who were introducing critical perspectives into a theatre dominated by bourgeois-appealing jingoistic, upper-middle class social comedy drama, farce, and musicals). As he leaves, Maule holds stickily onto Garry’s hand, not wanting to be ejected.

Like Daphne, he is disentangled from Garry (or ‘distacted’ shall we invent a word and say, from a glue-like sweaty hold). In the extract, Scott as Garry (in a move not in the script) washes his hands in a finger bowl, presumably of rosewater, before calling for his private secretary, Monica. Once his hand is freed. Maule’s sticky emotion is not only disregarded as too ‘Uckfield’ in its boringly earnest manner but found distasteful. I am not sure yet how that feels being watched in context by this queer working-class-origin identified witness.

Roland Maule takes leave of Garry after their first meeting

The actor playing Maule (see above) overacts his sticky hold as he is presumably directed to do, as he also overacts for laughs, some tortured facial expressions. Of course it will be funny, but is it right, I wonder to reproduce the ridiculousness people once saw as inalienably associated with expressed love (prepared as it is to be asexual as Maule articulates this) of a ‘grown man’ for another ‘grown man’. In the 1930s, although adolescent crushes were exempt from overmuch fuss given the experience of public school by the male ruling class, heteronormative hegemony about exprezzed feelings of love is assumed to be absent between ‘normal’ grown men. I will come back to Maule later.

But first we should return to the idea of acting and performance. Overacting, rather than just acting, as it is done on a stage, is acting, but not according either to Stanislavskian naturalism, which is the norm of Coward’s drama. It is demanded by the conscious rejection of the mimesis of ‘real’ emotion, other than as a deception, to increase comic effect as pathos oft does. Yet it is played on consciously in this play.

Take this exchange between Liz, who seems to be the directing consciousness of Garry’s acting style. She is,, besides still his wife, the leader of what she calls at ths very end of the play ‘the firm’ which finances their lifestyle and who says her role us above all to stop him overacting. By the word ‘overacting’, she implies not only his theatricality but his flamboyance with his earnings, intended in her mind to keep ‘the firm’ afloat on his earned liquidities. [5]

Liz, unlike the other lovers (being women and less regarded men in Gary’s life) no more believes that there is a real Garry Essendine, that is not in some way a performance, than does he. Others feel they see his essence, and it is the essence of a man capable of being loved intensely by them. The other mature woman in his life, the married Joanne, another resident of the ice-cold guest room, says to him:

I want you to be what I believe you really are, friendly and genuine, someone to be trusted. I want you to do me the honour of stopping your eternal performance for a little, ring down the curtain, take off your makeup up, and relax. [6]

Roland’s take on this repeated scenario is the most interesting because the most despising of the persona that Garry plays on stage and, in the world of the play, off it as well, that of Noël Coward, notoriously associated with the words Coward himself puts in Maule’s mouth to describe alter-ego, Garry.

Every play you appear in is exactly the same, superficial frivolous and without the slightest intellectual significance. .. All you do with your talent is to wear dressing-gowns and make witty remarks when you might be really helping people, making them think.

When Garry dismisses all of that with an authoritative knowledge of the ‘theatre of the present’ (to wit 1930s London), Roland can only fall back ‘hypnotised’: I had no idea you were like thus. You’re wonderful!’. [7] But what Garry IS, in their minds and ours, is impossible to articulate other than not being that which he enacts. This phenomenon is aligned to the enactments and performances demanded by patriarchal heteronormative capitalism. In the latter, one produces products that sell, appeasing as you do the values of the old rich (the aristocracy represented by the nouveau riche Lady Saltburn, the mother of Daphne Stillington) by promising to put their offspring on the stage. That end is one much desired, after all, by the Mrs Worthingtons of this world captured in Coward’s celebrated song (you can hear and see it at the link).

The queerness in the play, however, hides in plain sight, explained sufficiently by the values of the bohemian artist of the period. Young men, just as does Mrs Worthington’s daughter, yearned for the stage too and perhaps for the bohemian queer opportunities that went with it. In the play, take, for instance, the mention of that son of an ‘awful Admiral in Rugby’, who having become a sailor, as we shall possibly see that in itself for the period was another code for queer inclination, that Garry met ‘at a dance in Edinburgh when you were up there with Laughter in Heaven and swore to him that if he left the Navy you’d give him a job on the stage’. The words are from Monica, the keeper of Garry’s social diary [8].

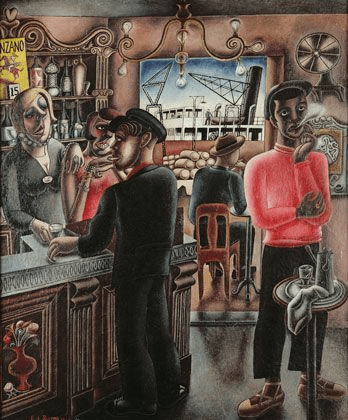

As if sailors, with a nouveau riche background were not enough, Monica also mentions ‘Joe’, a stereotypical working-class sobriquet, possibly of a soldier in the army serving in the Empire and living in India. He met him, says Monica, in the South of France (Marseilles being notorious for such meetings – see the work of William Burra exampled below – but it is clear that, though he says ‘Joe was wonderful’, it was likely that he does not remember him precisely since he also says he is ‘dark green and comes from Madras’. Even the mention of the South of France only raises from Garry the witty retort: ‘I do get about, don’t I?’ [9]

But some of the queer code is less obvious and is found in that part of the humour that only contemporary queer men might have known. Joanna, intent on netting Garry as an extra-marital lover buys, like Daphne and Roland alike, a ticket for his boat to Africa. When Garry says,’You’re not a good sailor,’ she retorts, ‘I am a perfect sailor’. That she was imperfect in the sense of still not being a male would be the underlying joke here.

The culture that produced such subterranean laughs in part of the audience is described in both Paul Baker & Jo Stanley’s book, ‘Hello Sailor!: The Hidden History of Gay Life at Sea’, and a chapter of Stephen Bourne’s ‘Fighting Proud: The Untold story of The Gay Men who served in Two World Wars’ (see my blog on these at this link). The suppressed joke of this type also plays on its denigration, I suppose, of the ‘innocence’ or ‘gullibility’ of women with regard to masculine sexualities in tales of ‘ship’s stewards’ in the at that explain how the working-class Fred first came into Garry’s employ as a ‘valet’, a man whose behaviour is, in Joanna’s view, rather uncouth.

Garry says in explanation: ‘He was a steward on a very large ship’, an explanation that does not fit with Joann’s view of the ‘good manners’ of most such stewards, whilst for the prudish Miss Erickson, ‘He is the only one I know’. At which every queer and queen in the audience would titter, or I would anyway.

Of course, there are also coded hints in the play that few men were as ignorant of queer dalliance as thought. After all in the period, only passive queer men – those willing to be penetrated by another man – were thought to be truly queer, an idea rife right up to the nineteen-fifties, as experienced by queer artists like John Minton and Keith Vaughan – see for example the blog at this link.

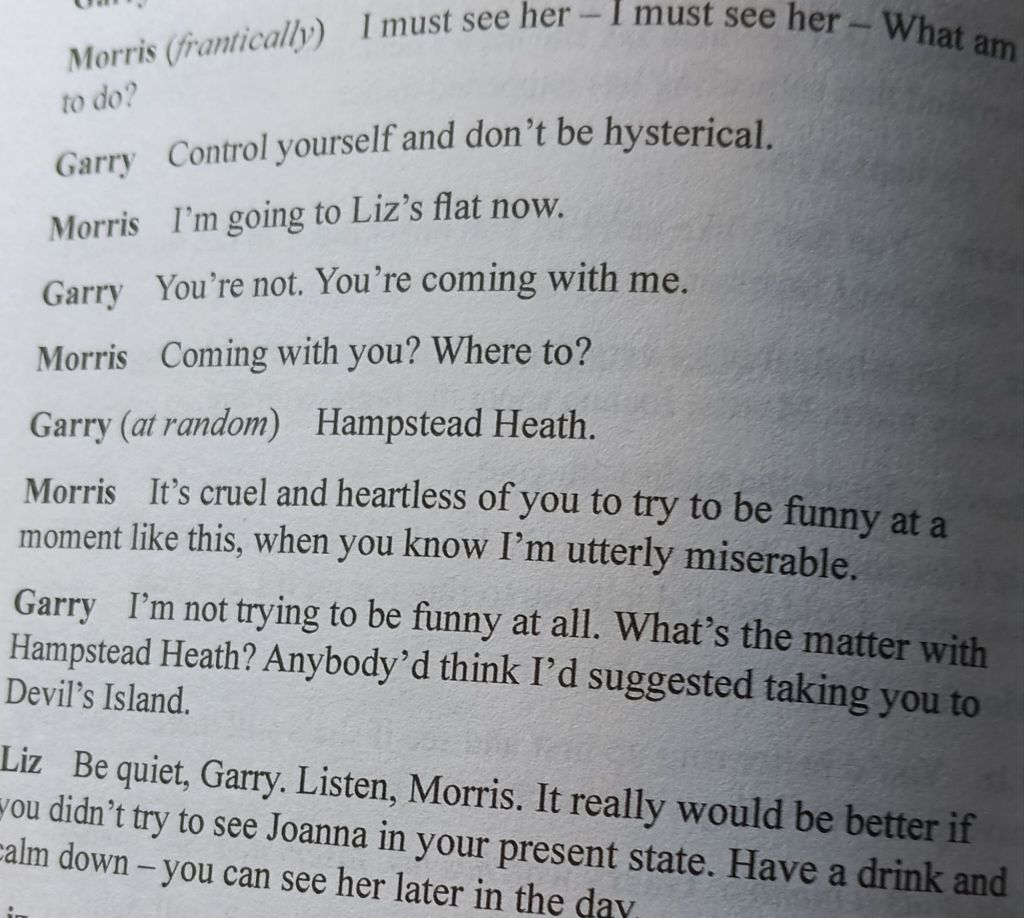

There is a particular subterranean reference to this in Act Two, Scene 2, when there is an exchange between Garry and Morris, the convenient mask sexual ‘affair’ for Joanna Lyppiat (Morris being a friend of her husband, Henry Lyppiat, for her attempt to snare Garry into a real sexual affair. Morris does think he is Joanna’s sexual choice, too, but that is how such complexities of queer choice are coded.

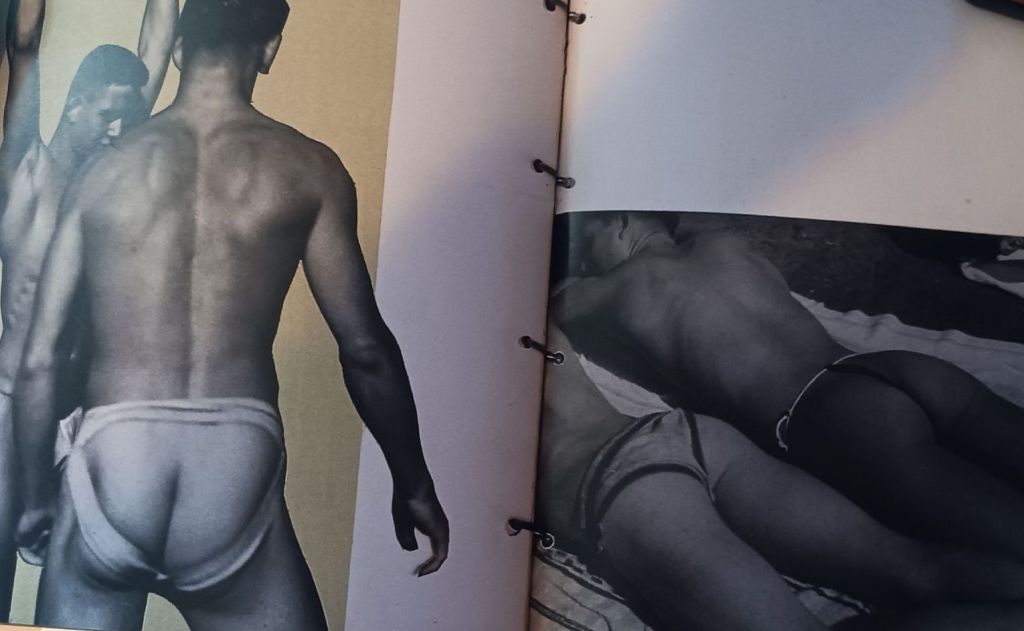

In this passage of exchanges, the ‘neurotic’ Morris is put in his place by Garry reminding him that he has no right to see Hampstead Heath as ‘Devil’s Island’, presumably because he already knows it. Morris does not speak again for several pages, nervously, I suppose, downing his guilt with the strong drink Liz has handed him. Perhaps you already know that Hampstead Heath was notorious as a place for nude male bathing, and its reputation was decidedly queer, as these 1933 pictures from Keith Vaughan’s early career (kept in a private album intended for friends only) show.

Hampstead Heath scenes from ‘The Highgate Ponds Album’ 1933 in Gerard Hastings (2013: 35ff.) Keith Vaughan: the Photographs The Pagham Press.

Roland Maule therefore is not the sole representative of queerness in the play, though he certainly is the only one whose attachment to men is thought of as a predominantly emotional one. On his first expulsion from the flat in Act One, he is reported to be sitting on the flat’s stairs ‘crying’ by Henry Lypiatt. Morris Dixon asks of Garry ‘What have you been up to, …?’, perhaps half-aware of scenes of rejection of male lovers in Garry’s past (but we will never know). [12]

So much is he played as ‘in love’ that Roland claims that that he is ‘absolutely devoted to’ Garry’s ‘face in every mood’, feels that Garry is ‘part of me’ and has given up his law studies in order to travel, even if in the ‘steerage’ of the ship. He declares that his love will not ‘make any demands on’ Garry. To which statements Garry replies: ‘You mean you don’t expect me to marry you!’ [13]

The tone is light at all points but, whilst all the women who make similar protestations are allowed to leave their enclosure in another room, Roland is never seen again before the curtain and the world of the play closes on him, stuck there. The statement for why this may be may be is tongue-in-cheek, but I think only partly is that the case. Garry says to Monica: ‘He terrifies the life out of me’. [14] ‘Can anything good come out of Uckfield?’ we almost expect him to say, together with other Pharisees in previous divine literature?

When I have seen it, I will report back if Andrew Scott and the National Theatre company surprise me with their take. I rather hope so. Meanwhile, I look forward to seeing a play I would from its reputation as high society comedy have run a mile from in preference to seeing it. The issue is that it is a totally self-conscious piece. Yes, people do run in and out of various doors to surprise themselves and each other for comic effect like a French Farce. The point is, however, that the play has to make our feelings about its generic lightness evident so that we see there may be underlying issues. Henry Lypiatt, reporting a conversation with his wife, Joanna, on the telephone (who is, unbeknownst to him, only next door on an extension phone line) says to Liz who does know this, and reporting Joanne’s unheard words: “She says she feels as if she were in a French Farce and is sick to death of it, she sounds upset’. [15]

We see the streamed play and the delightful over-talented Andrew Scott on Tuesday. I think I have talked myself into enjoying it a good deal. But let’s see.

with love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx

[1] Russell Jackson (2023: v) ‘Introduction’ to Noël Coward Present Laughter London, Methuen Drama

[2] Noël Coward (2023: 15) Act One, Present Laughter London, Methuen Drama

[3] Ibid: 17

[4] Ibid: 16

[5] ibid: 31

[6] Act 2, Scene 1, ibid; 5

[7] Act 1, ibid: 38f.

[8] Act 3, ibid: 88

[9] ibid: 86

[10] Act 2, Scene 2, ibid: 62

[11] Act 2, Scene 2, ibid: 76ff.

[12] Act 1, ibid: 42

[13] Act 3, ibid: 96f.

[14] Act 2, Scene 2, ibid: 77.

[15] Act 2, Scene 2, ibid: 79

This was such an fascinating read!!

LikeLike

Thanks Aaron. I saw the play last night screened and will blog today on my response. It was wonderful. They queered the play more and so brilliantly. In brief, Joanna becomes Joe.

LikeLiked by 1 person