In what follows I do not intend to exoplain the terms used to describe Greek ceramics. For a brilliant introduction, and if you do not want to read Robin Osbourne whose book is discussed, which i recommend most, see the new York Metropolitan Museum’s online piece (at this link).

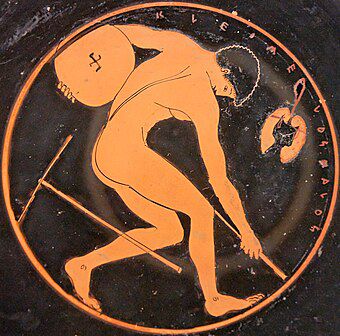

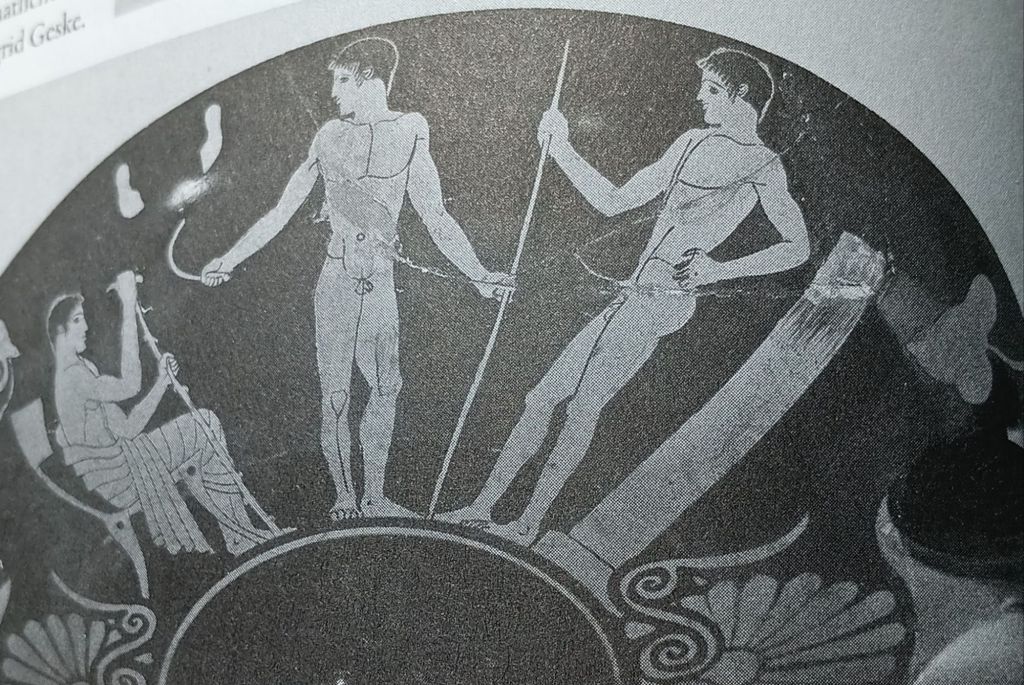

The ‘kalos’ inscription, a statement of a young male’s beauty, is common on Greek pottery. Sometimes, a named figure, as in the example above, is praised as beautiful because of the athleticism, mastery, and consequent beauty of the body of that young man. Above, the man is named Kleomenos. However, since Kleomenos means ‘he of beautiful limbs‘, it is possible that the name used is a typification of the ideal athlete and not a ‘real’ young man. Of course, we can’t rule out that parents sometimes name their children with such future expectations and pressure on their children thus, or that this was a admiring sobriquet.

It isn’t clear then, unless we have other complementary data, which may or may not existbin this case, about the real young discobolus [discus-thrower] supports his ‘reality’ whether this inscription is about a specific male or about a generalised feeling about what makes a boy ‘beautiful’. It may encourage, for instance, the ‘virtue, that leads to the beauty of the body. By ‘virtue’ I invoke it’s older sense, as Chaucer uses it in The Canterbury Tales, the older sense of a quality, which indicates a quality, such as athleticism, fitness and strength, at its most excellent rather than indicating only moral excellence, as it later became. Whether the inscription then is about the embodied beauty of one young man, or a mnemonic for an older man at a drinking party of where he should exoect to look for fulfilment of his erotic needs, it links male beauty to a wish, fulfilled in a real Kleomenos or not, to have access to ‘he of beautiful limbs’.

Young or elder males might see in the bottom of their drinking cup (a kylix) as they drain the wine in it, both how the boy they wish to love, or lust for for temporary relief, might acquire, or how they themselves when younger acquired, male beauty by excellence. Their procedure and tools are in the range of athletic activities pictured on the ceramic drinking-bowls interior.. often there acti ities are, in this case illustrated in action raround the shaped ring. Of tje bowl.

In summary then, the Wikipedia account on this subject also tells us, on Greek pottery, it was common to find the inscription that sometimes identifies a young man by name and describes him as beautiful but that:

Some inscriptions are generic, reading only “the boy is beautiful” (ὁ παῖς καλός, ho pais kalos).[3]

What Wikipedia also tells us is that the phrase is also usually used in relation to contexts of openly expressed erotic desire, Platonic or otherwise.

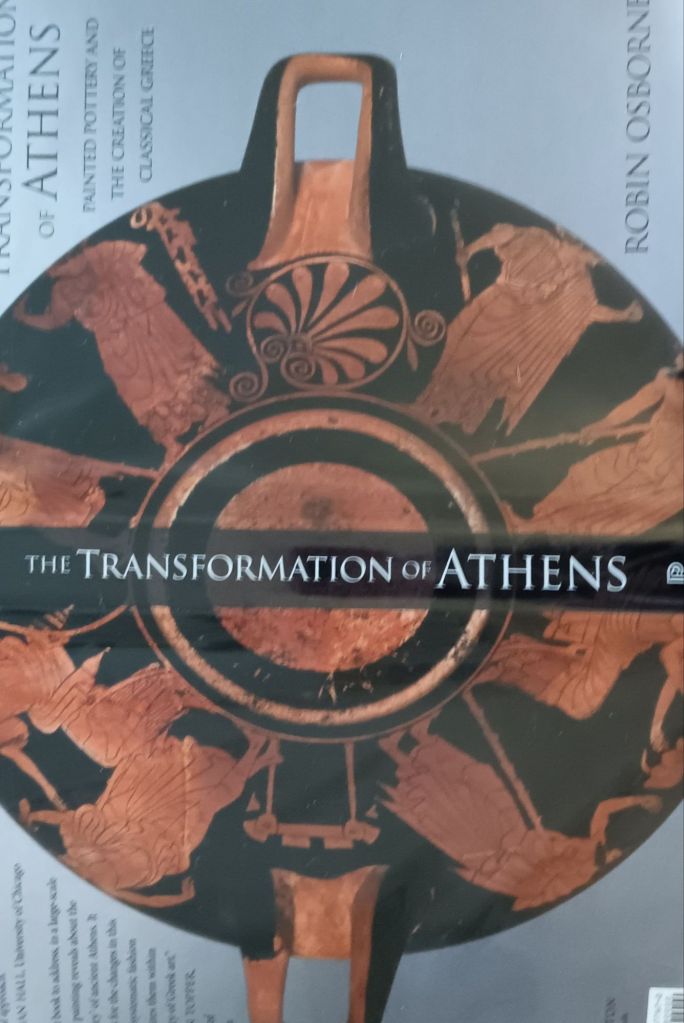

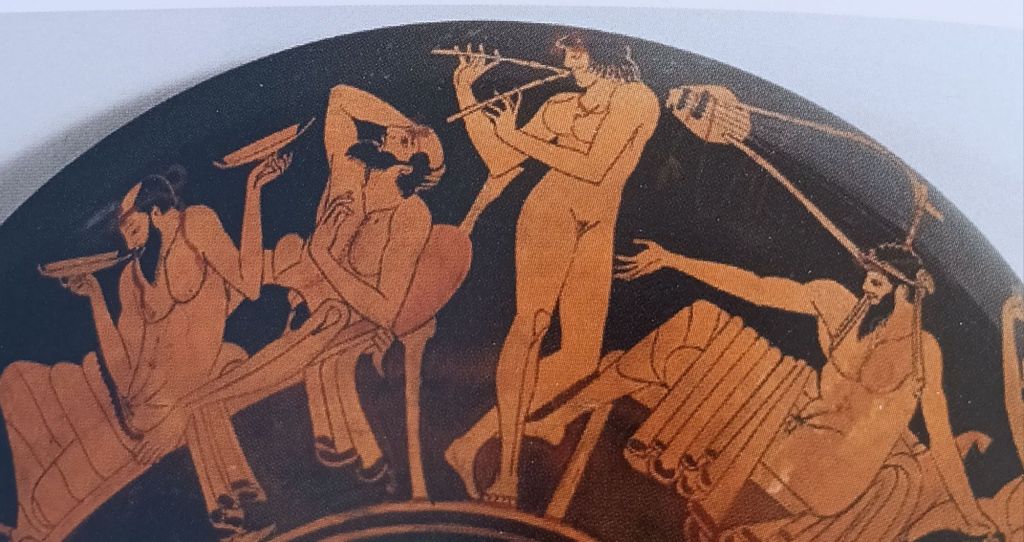

The earlier the red-figure cup, the more likely the depiction of actual erotic activity, Robin Osbourne suggests in his wonderful book published in 2018, The Transformation of Athens: Painted Pottery and the Creation of Classical Greece. Osbourne’s book is highly readable without any loss of academic rigour.

Osbourne’s argument is that there is a transformation in the content and treatment of it in red figure painted ceramic art that occurs precisely in the period between the sixth and fifth centuries BCE, and that aligns with the creation of the politics of Athens towards democracy and to attitudes that harmonise with democracy as the Greeks knew it, and which addressed wider range of classes and created a new identity that emphasised the shared nature of human being rather than celebrating competitive individual action of a driven nature.

He illustrated this best in looking at the treatment of the training gymnasium, wherein frequency counts of contrazyed themes and their characteristic style ( for he sees theze as related issues) of pots at the early and later end of his chosen period (550 – 420 BCE) show a preponderance of either active individuals, in the interior of the cup’s bowl or athletes engaging each other in competitive endeavour, like wrestling. Alternatively, if the sport is based on sequential trial, as in archery, we see the implements.

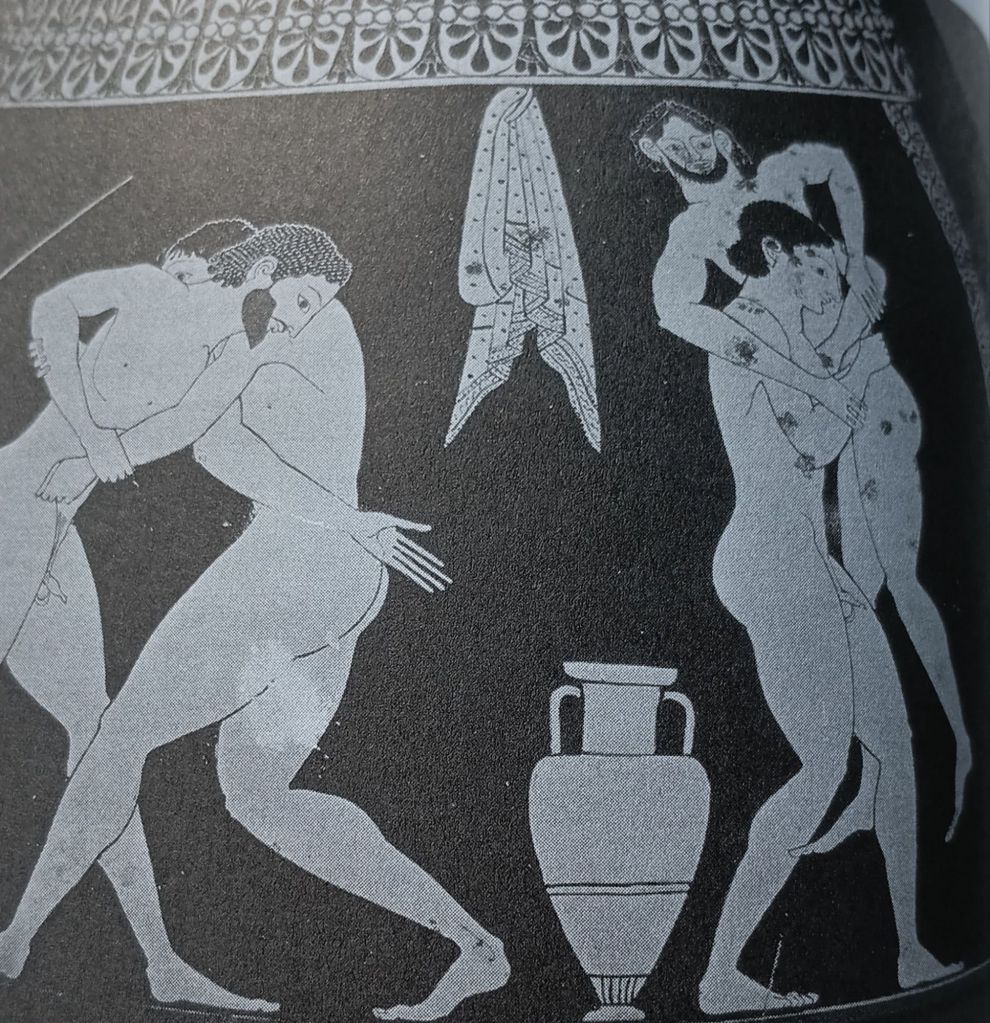

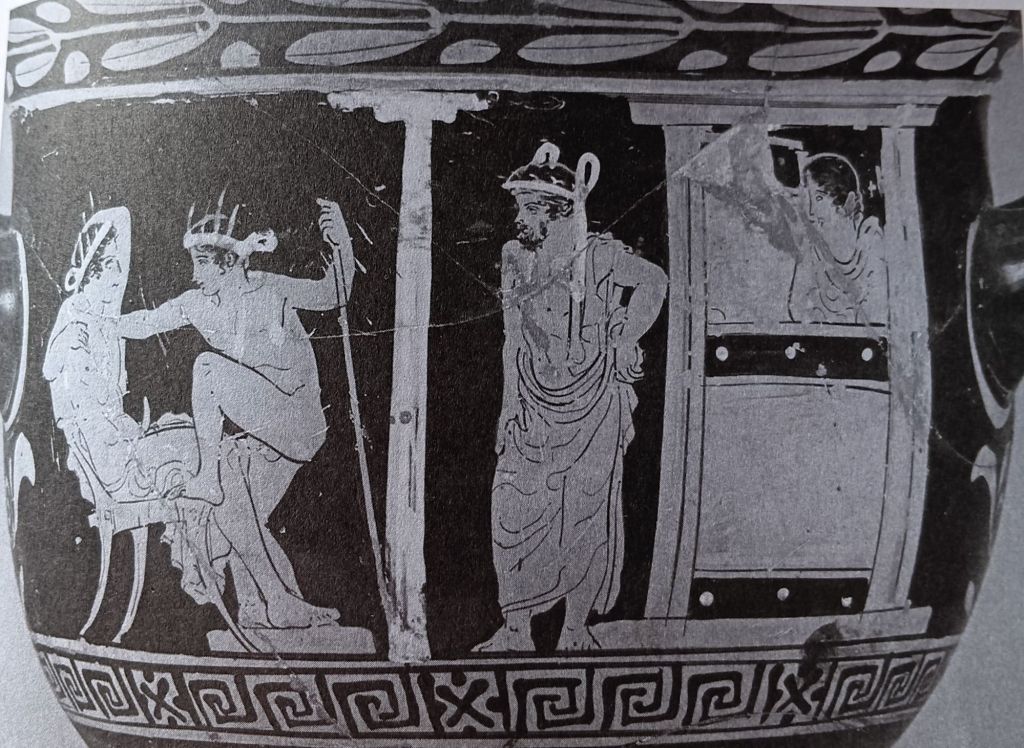

The side of a red-figure amphora signed bu Andokides as pottery, c. 520.

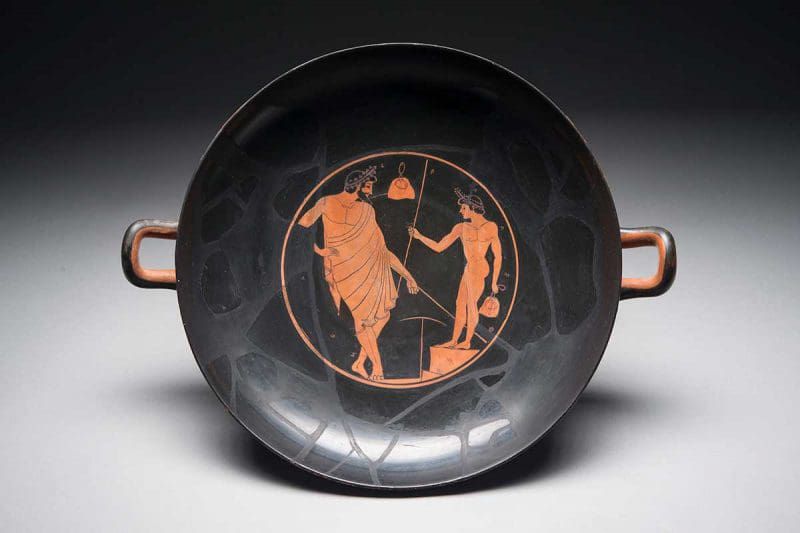

Lots of examples are in Osbourne’s book, both in full description and illustration to show that in the later part of the period, red-figure painting of gymnasia events or participants, the gymnasts are more likely to be shown, not in the midst of active sport engaging other males competitively, but in the common grooming processes related to the gymnasia, and in poses attracting visual attention of characters on the pot itself.

The painted admirers and appreciators act as prompts, Osbourne suggests, to the owner of the pot and those men enjoying his hospitality at a symposium to likewise contemplate the beauty of Athenian male youth. The young men are more likely to be holding objects involved in grooming, such as the strigil with which he wiped dusty sweat from his body than an implement of competitive sport. Moreover, theze figurez stand at relative distance from each other rather than physically interact with their bodies.

One side of a red-figure kylix attributes to the ‘Villa Giula Painter, 460 – 450.

In effect, the aim is to admire the idea and feeling of being in a social event of which we could imagine ourselves, average Joes though we may be in fifth-century Athenian democracy, once intended for more exclusive groupings. such as co.petitive members of oligarchies. We imagine ourselves in the role of a participant painted on the pot, celebrating generalised Athenian beauty and good governance, even that of the non-Oedipal family.

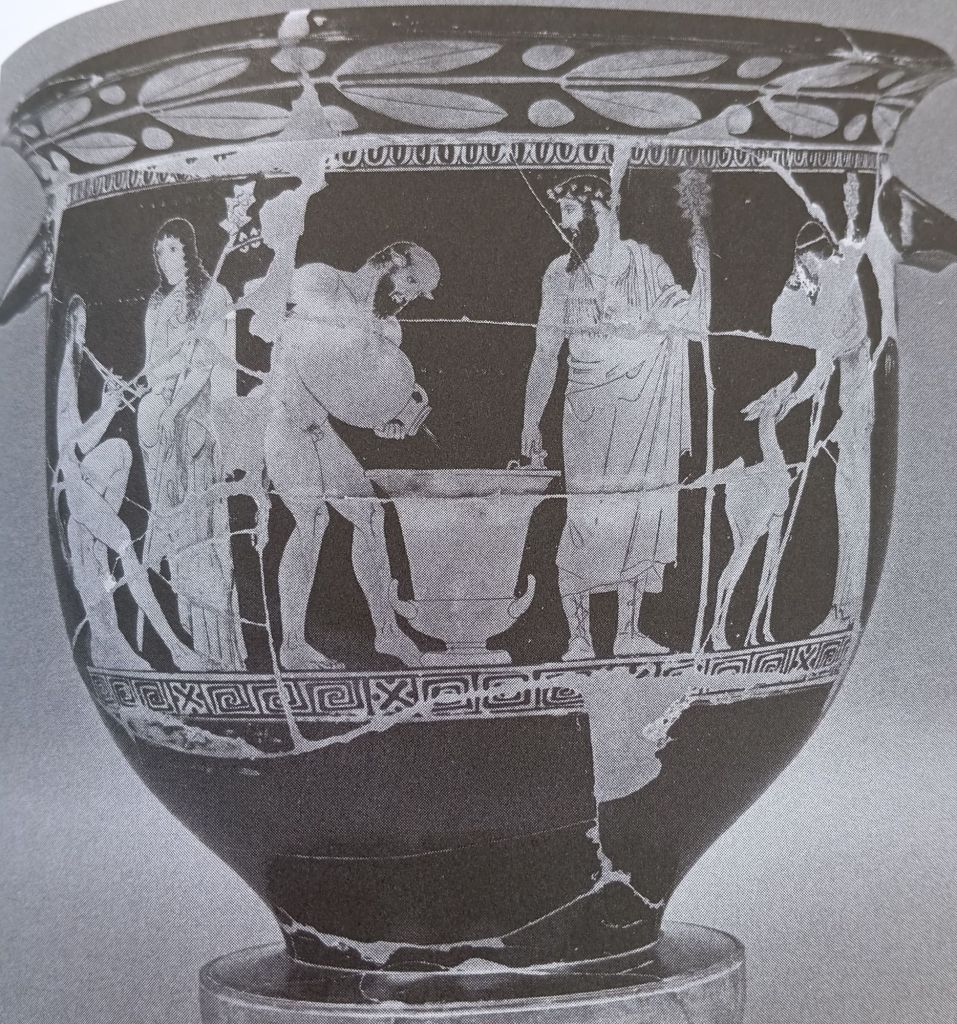

Exterior of cup attributed to Makron c. 489 depicting the blessing of a man by his wife as he goes to war or a journey.

In a different description of the effect Osbourne tells us that we (and we are to consider ourselves assumptive males) do not admire the activity in the moment of a drama wherein a specific character, named or otherwise, seizes his opportunity to gain recognition as an athlete but instead boasts the virtue of male beauty itself in appreciative eyes. Osbourne says similar things happened when the subject of the pot was war and warriors, partaked in cult ritual, lovers of attractive bodies and/ or sexual opportunists (with young women or young men) or symposium members (think party-goers).

Exterior of cup attributed to the Foundry Painter, ca. 480

Such a change involves, Osbourne further suggests, painted characters who can be imagined as having choices based on interior mental processes and who do not metely act in lieu of the absence of such processes to prove their individual superiority over others. Hence, they are pictured in the layer ‘classical’ period of the fifth century [up to the return of oligarchies in Greece in the fourth century] as quite unlike the naked heroic beauties of earlier times, whether in Archaic period black-figure or early red-figure in the sixth century, as more likely to be clothed than naked, non-individuated, or masked in a slightly more metaphoric sense than in Greek theatre. The mask is the likeness to each other of aversge men of the democracy. Such characters allow the viewer and purchaser to see themselves in the role of any of the characters portrayed on the pot, other than slaves or women. Hence, the characters are largely inactive or pre-active; still thinking about what to do and making free choices. They, hence, are less likely to be in direct interaction with others pictured there.

In earlier forms depicted on pottery characters, whether engaged in sport, war, sexual competition, or at a party, are all over each other, for it is precisely competitive action that counts. In later ones, there are negotiable distances between figures. There is also more respectful picturing of women, and indeed young men who are the object now of something more like romantic or affectionate bonding. Even satyrs act like they know the duties of family rather than rampant sex in the later pottery. Below satyrz serve both male and female members of a family, but not by raping them, in the manner of the license that could be represented in earlier pots featuring giatish satyrs.

Bell-krater attributed to Lykaon Painter, ca. 440.

When it comes to representations of sexual activity too, there is we are told, more sobriety in the late Classical period of the fifth century. There is more interest on the pots, Osbourne says, in sex with women rather than men in the later period, but never exclusively, it seems. If the subject us satyrs, then what Greeks would consider the more animal instinct in pleasurable sexual 8nteractiom could be explored. Below the partners engage in anal and oral sex, or crossing boundaries of the animal-natural and supernatural in the representation of sex with a sphinx.

Exterior of a cup attributed to the circle of the Nikosthenes Painter, before 480.

Osbourne believers that democracy killed the licence for which there was a taste in pre-Classical Attic Greece, then, even in satyr representations. Even courtship bowls disappeared, usually the courting of a beardless youth by a bearded adult male, always with gifts (often animals and playthings), and in early pots with much fondling, of chin and penis of the younger male by the grown man to be displaced by scenes of chaste encounter between men and women before marriage, as in examples Osbourne shows fro the Wedding Painter (though no-one is sure that weddings are intended). The queerest is of asexual encounter between males, that has Osbourne says, no precedent and is hard to read. With no academic reputation to defend, I would say that this scene is important but still restrained because it shows sex between two unbearded youths about to occur but authorised by elders, a mature man and a mature woman who views the coupling from behind a screened door. though Osbourne does no say so, it recalls the practice in Crete spoken of by Anne Carson, classicist and poet, of authorised queer matches blessed by the parents, usually of two aspirant families eager for an alliance, in stories from Crete.

Bell-krater attributed to Dinos Painter, ca. 420

In dealing with symposia or male drinking parties, Osbourne points to their change from youthful revels to more sober affairs, more sober at least sexually, though sex occurred with men and / or women (these often being sex-workers or slaves, who could be of either sex). He refers of course only to representations on the ceramic container used in such symposia. The most interesting fact here, however, is not the decline of the representation of revelling male youths, or komasts (from komos – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Komos), who decamped from the party inside a home onto the streets, but the decline of ‘queer’ (in our modern sense) party scenes called ‘booners’, also part of the komos. Booners included ‘bearded men wearing the chiton as well as the himation, a form of turban-like head covering, and sometimes earrings, and often carrying parasols’. Those persons may be nothing other than an imagination of certain aspects of partying, that makes parties seem ‘ a glimpse of a world that was other’ than the norm.

They take the sensual aspects of the symposium, its music and song, its beautiful clothese, its deliv#cate light, the bouquet of the wine and the scent of perfume, the dancing bodies of those providing entertainment and they make those sensual aspects what is reperformed n the ongoing revel (1)

The booners disappeared from the repertoire of later red-figure ceramics in which otherness no longer featured though choice of sexual play between men and women did for the male participants. However, none of this moderating and/ or socialising of the representation of the active impulses of the animal body of human beings changes the fact that the pursuit of that describable as ‘kalos’ was your goal and was not a word dictated by sex/gender distinction, as became the norm in later civilisations, although none as rigorously as in the nineteenth and twentieth century AD. after the Second World War and well into the late 1980s, there was intense pressure to police the representation of permissible language used of sex / gender binaries.

When I grew up as a boy in the 1950s and 1960s, an attractive man could, without consequence, be described as ‘handsome ‘ but not as ‘beautiful’. The latter involved crossing boundaries that guarded sexual identities in terms of the relationship between and within male and female groups. sometimes, or hide bound notions of gendered linguistic appropriateness. The debate about this continues on the global internet in relation to the English language I found out recently.

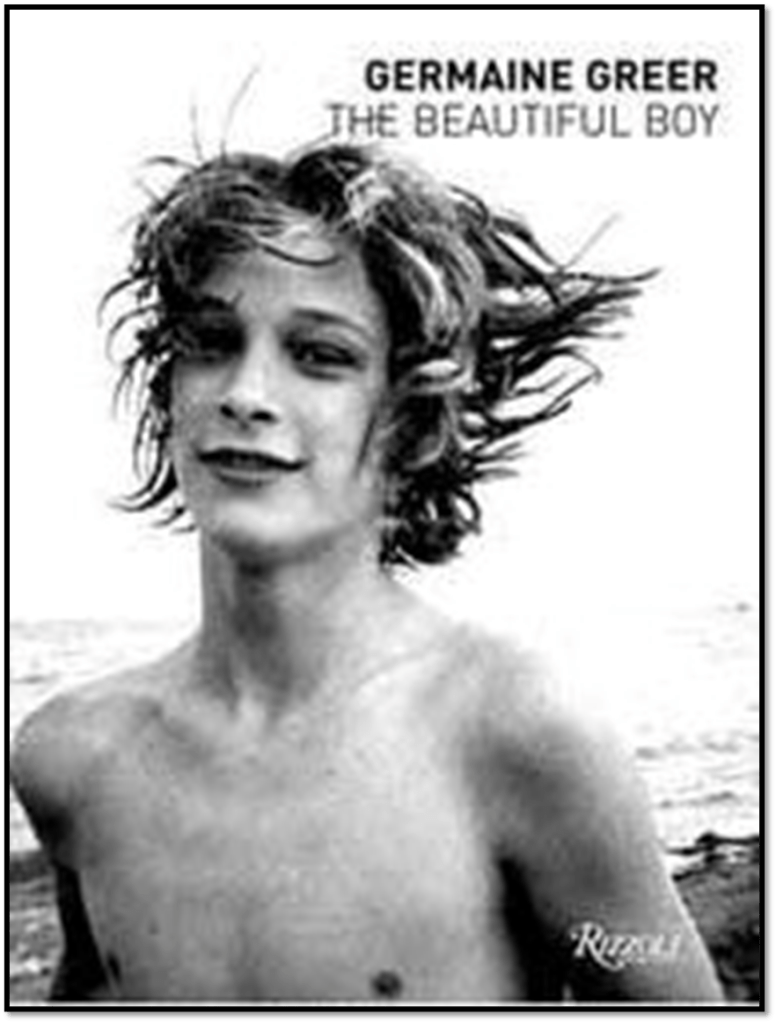

This did not relate only to how men described other men. In 2003, feminist literary critic, Germaine Greer published a book called The Boy, which in later editions was renamed The Beautiful Boy. The point was to reclaim the right for ‘biological women’, as we have come to find was Greer’s focus, to find young men sexually attractive and to find a language for making this public, as already existed in patriarchy for ‘biological me’ to talk about young women. The book came out with a picture of , in the words of Wikipedia, ‘Björn Andrésen, a Swedish actor and musician who played Tadzio in Death in Venice (billed by the director Luchino Visconti as “the most beautiful boy in the world”). Andrésen ‘stated in the press that he objected to the picture having been used without his permission’, whilst Greer and her publishers insisted that only the photographer’s permission was needed, that photographer being David Bailey. The controversy certainly highlighted a contradiction in attitudes to the use of photographs of young women, even with their permission but more so without it.

Wikipedia , a useful summary, is good and balanced ion this and other controversy around the book. This description is not commented upon:

Greer has described her book as “full of pictures of ‘ravishing’ pre-adult boys with hairless chests, wide-apart legs and slim waists”. She goes on to say that, “I know that the only people who are supposed to like looking at pictures of boys are a sub-group of gay men“, she wrote in London’s Daily Telegraph. “Well, I’d like to reclaim for women the right to appreciate the short-lived beauty of boys, real boys, not simpering 30-year-olds with shaved chests.” She was criticised for these comments, with some writers labeling her a paedophile.[8] Greer responded vigorously on Andrew Denton‘s television talk show Enough Rope. Denton quoted her as having said to the Sydney Morning Herald that, “A woman of taste is a pederast—boys rather than men.”

I don’t intend to comment upon the paedophile accusation, though its resurrection as an unfounded accusation against trans women by some radical feminists means perhaps one ought to do so. The important thing is that Greer knew she was revisiting an issue long discussed in relation to Classical Greek sexualities, though an issue sometimes conflated by the age range referred to as ὁ παῖς καλός in Classical Greek inscriptions, or in the use of the term ‘boys’ in male queer culture in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries AD. For Greer this becomes a matter of ‘taste’, by which I take it she means appropriate aesthetic discrimination, equating herself with the same appreciation that typified Socrates, Plato and Aristophanes and attracted each of them, presumably with political reservations, to Alcibiades, a a yet beardless warrior and rather bad politician but by reputation, a very good example of ὁ παῖς καλός.

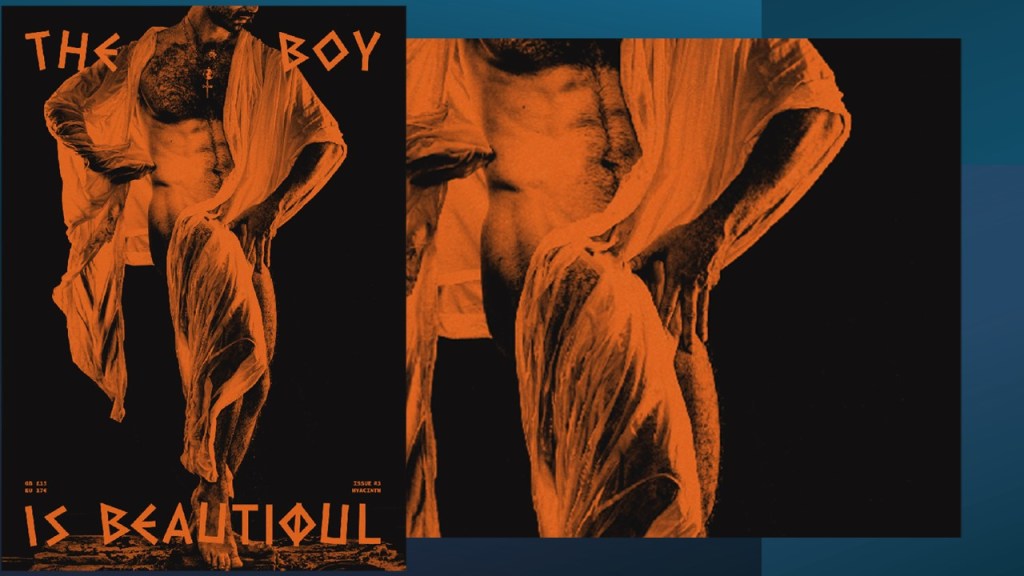

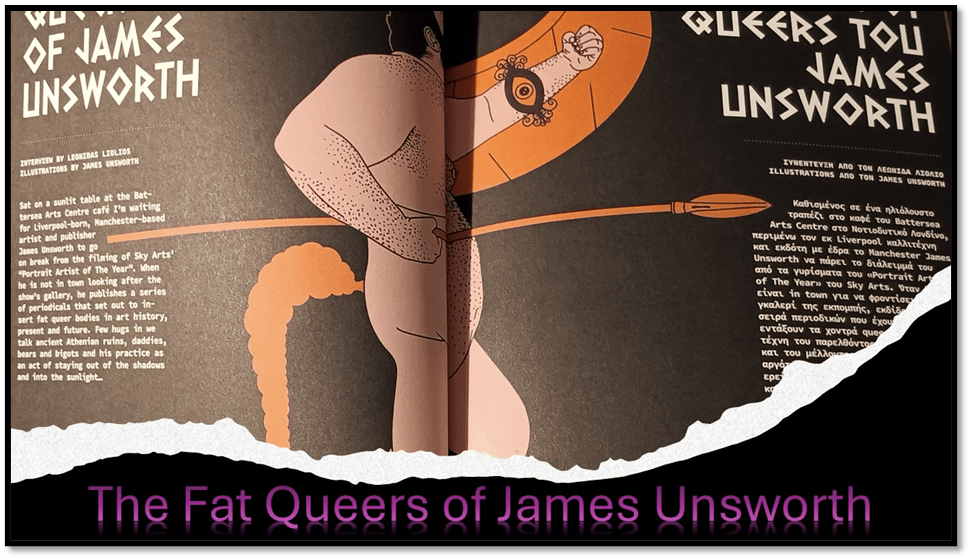

Queer culture in the twenty-first century uses ‘boy’ to indicate attractive men, it would seem if we use as evidence (partial as it may be) of the publication, The Boy Is Beautiful, of which I came across the most recent issue (number 3 only, named ‘Hyacinth’ (after the beloved of Apollo) published by an Greek man, Leonidas Liolios, living in London and in part, for for it uses parallel Greek and English text, self-identifying Greeks ( though published in the UK, if with a global sales pitch). Its motto has a font that gives all that away, as does its celebration of Classical Greece as a place of the multiple colours painted on the statues we associate with cold white marble. The artists who own Studio Prokopiou, Phillip Prokopiou and his life-partner, Panayiotis Poimenidis (Panos for short), are interviewed in the Hyacinth issue and point out that , or at least Phillip does, that he has ‘a real issue with “good taste”. It is worth remembering this when we discuss Germaine Greer later. He goes on to explain:

When I discovered that these marble sculptures that defined the Western standards of beauty – those “perfect”, “ideally sophisticated” things – in reality looked like some kitsch souvenirs or kitsch figurines, I was gobsmacked! … It’s just hilarious that people are so clueless about that fact that those white marbles that are considered the pinnacle of taste and high art didn’t actually look anything like that before they were scrubbed clean by time or design. They had like bright pink skin and yellow hair with fucking diamond eyes and multi-coloured dresses. (2)

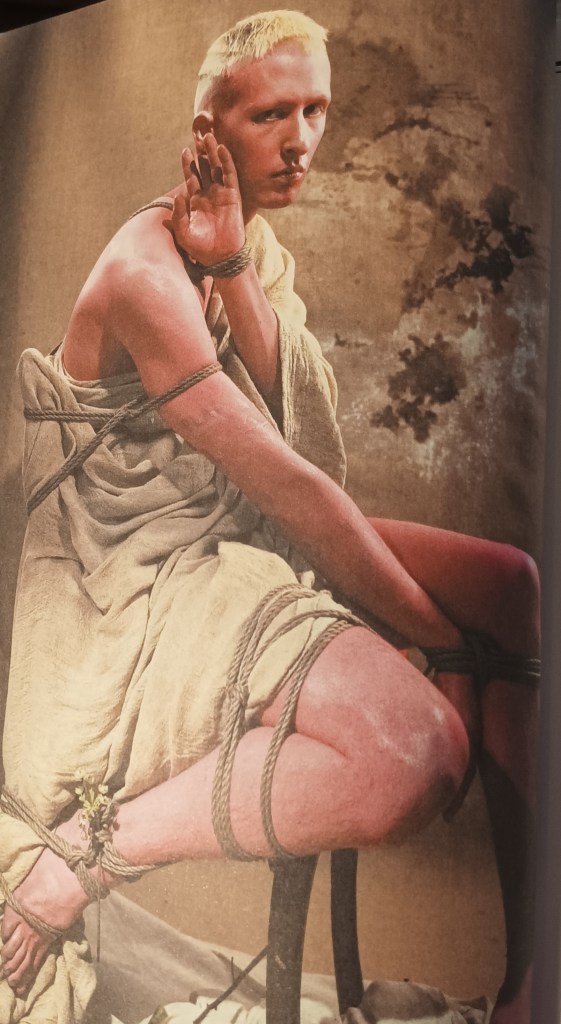

Scholars can back up the point about the ubiquity of polychromy (multiple colour use) on Ancient Greek statuary (use the link) but it is much more fun to see it explored conceptually in art. The artist do it by painting the naked body of their model for Eros in Pink, Alexander Dodge Huber, pink (literally) and then binding him in saclothth and tight rope bindings to show the meaning of good taste in action. Alexander appropriately puts up his hand in shame in being so brought down to conventional ‘taste’.

The ‘boys’ in this magazine share very few conventional categories of quality – age, skin colour, race, cis-or-trans-gender range or look. The ‘boy’ that is beautiful is the boy who is perceptible as beautiful by someone, however other to norms, in that sense, much like a character from a ‘booner’ scene. Here are more from Studio Prokopiou:

What matters too is that there is no promotion of sexual parts, as if this alone marks male sexual attractiveness in a boy deemed beautiful, the one penis visible in the examples lies in the natural shade created by the posture of the ‘boy’. Greek red-figure art, especially satyr art was rarely so coy. In another photograph in the magazine a penis is also see-able but in a piece that uses the whitening of marble statuary in Western good taste and the inevitable wear of time that tears fragments as well as colour from these statues to show how good taste excludes beautiful boys with differences in their body or its capacity, just as men of colour (a range of colour point out the good taste exemplum’s racism).

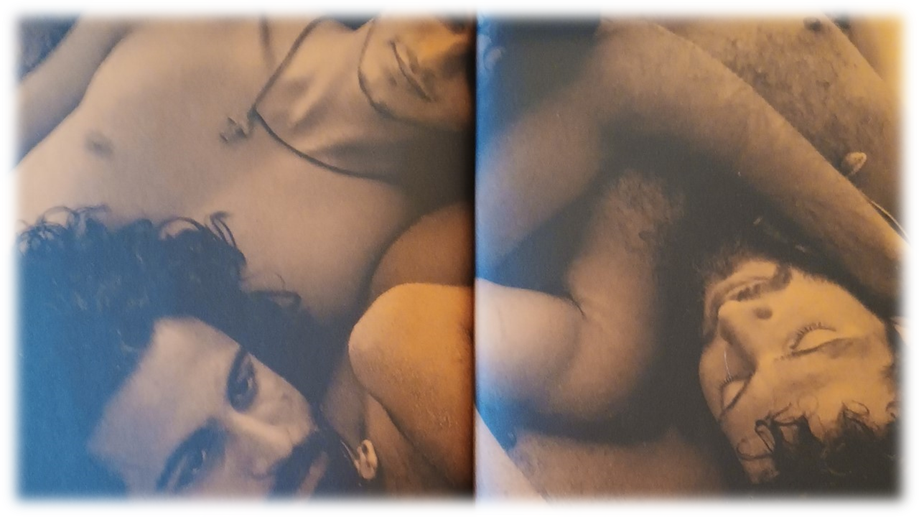

In another piece in the magazine Dario Laureano creates portraits of three young men (‘boys’) called Adonis, Stefanos and Kostas, who were photographed in fine group pictures set in Kedrodasus, Crete. . The beauty of these boys lies in the intimacy of the tripartite touching of heads and upper bodies in pictures that are about variation in mutuality rather than what we normally label ‘sex’.

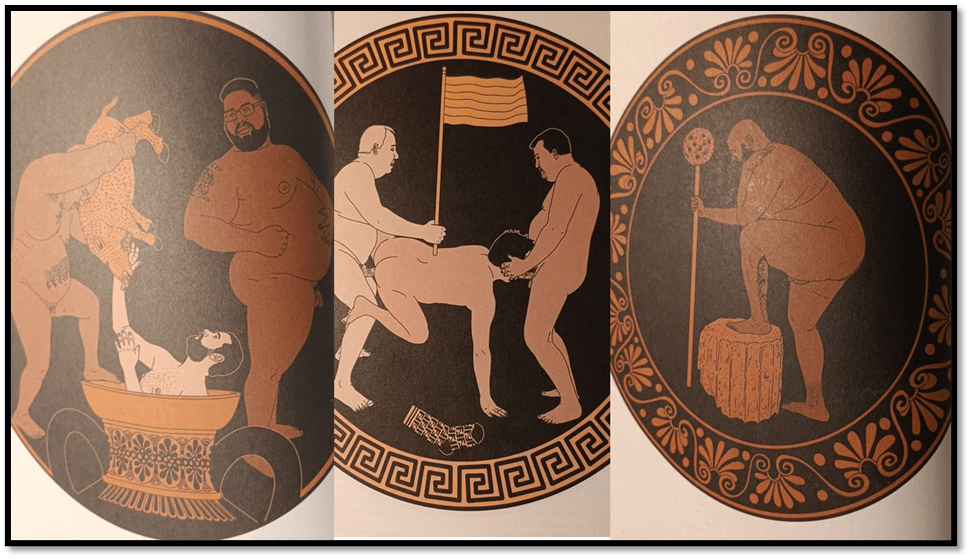

Yet as innovative as the take on the queer portrait in The Boy is Beautiful is, there is no doubt that much is missed, and particularly issues of older age bodies and bodies of a size not usually given status or consideration, perhaps especially, as our witness, James Unsworth, says in his piece in the magazine about his art, based on a spoof, as it were of the paintings in the interior bowl of a red-figure calyx. Meant especially to titillate in the Ancient model, Unsworth insists on describing in graphics types of person and practices often left out of the count of queer diversity, and usually in fear of association. Unsworth’s piece is The Fat Queers of James Unsworth and is an interview by the editor of the magazine, Liolios.

Unsworth shows some of the ‘fat queers’ as satyrs as in the title fold seen above but the satyr tale is added to a man in the pose of an early warrior, bearing a shield, bearing an eye motif, that indicates that Unsworth is challenging you to look at that considered unsightly in normative cultures, even homo-normative cultures. Are older fatter men seen as ‘boys’ too and is ‘this boy beautiful’. Unsworth even created bill-board size posters that confronted people in the City of Sunderland ‘with the idea that fat men are in fact desirable and sexual’. Personally, I don’t quite get the symbolisation of some of the practices brought into a more mainstream queer light, such as the piece in which a bore is used to force a naked fatter man down the neck of a huge amphora (in the collage below, by bespectacled big-bellied men in collusion, though one merely passively. Some seems athletically near impossible.

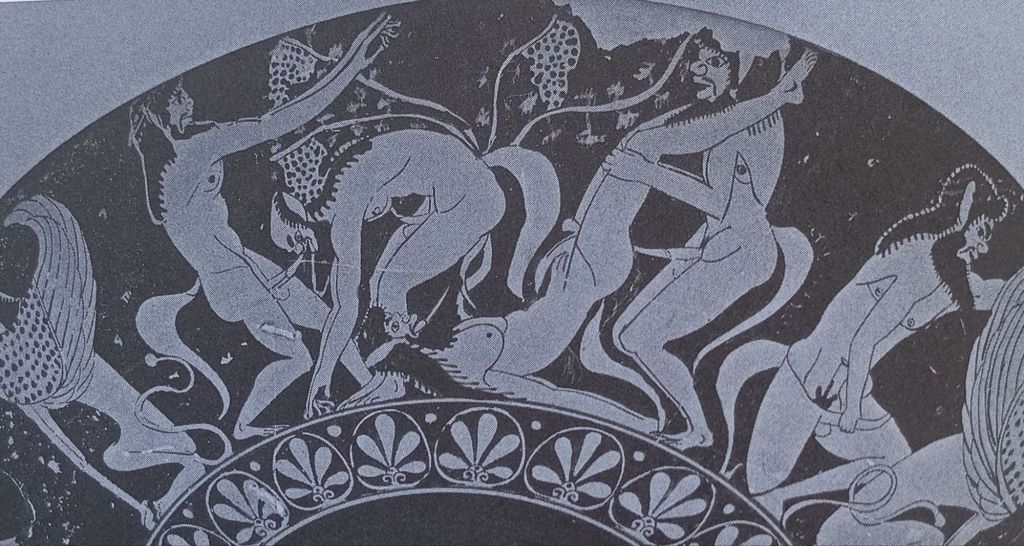

But the truth is this is true too of some of the practices in Ancient Attic red-figure work too. For instance take this illustration (c. 500 BCE) that Osbourne describes as giving ‘a modern viewer a strong impression of good-humoured larking about by these overexuberant young men’.

komos in a Red-figure cup, attributed to Epelios Painter, found at Vulci

Well, maybe, but much of the drunken revel feels like heavily sexualised play between the beautiful boys who grasp, at each other, launch themselves at each other and climb each other, bending conveniently over a huge container of what is certainly more wine. This is less komos, as Milton’s Comus (derived obviously from the komos. There never has been a naughtier pair of lines caught amidst two couplets than that I italicise and embolden in the below:

The Star that bids the Shepherd fold,

Now the top of Heav'n doth hold,

And the gilded Car of Day, [ 95 ]

His glowing Axle doth allay

In the steep Atlantick stream,

And the slope Sun his upward beam

Shoots against the dusky Pole,

Pacing toward the other gole [ 100 ]

Of his Chamber in the East.

Mean while welcom Joy, and Feast,

Midnight shout, and revelry,

Tipsie dance and Jollity.

Braid your Locks with rosie Twine [ 105 ]

Dropping odours, dropping Wine.

Rigor now is gone to bed,

And Advice with scrupulous head,

Strict Age, and sowre Severity,

With their grave Saws in slumber ly. [ 110 ]

We that are of purer fire

Imitate the Starry Quire,

Who in their nightly watchfull Sphears,

Lead in swift round the Months and Years.

The Sounds, and Seas with all their finny drove [ 115 ]

Now to the Moon in wavering Morrice move,

And on the Tawny Sands and Shelves,

Trip the pert Fairies and the dapper Elves;

By dimpled Brook, and Fountain brim,

The Wood-Nymphs deckt with Daisies trim, [ 120 ]

Their merry wakes and pastimes keep:

What hath night to do with sleep?

Well, of course, I am an old man now, and having spent long on this today I do need to think that the answer to ‘What hath night to do with sleep?’ is A GREAT DEAL INDEED. zzzzzzz!!!!!!.

Sleep well friends

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxx

_________________________________________________________

(1) Robin Osbourne (2018: 178, but see 175 – 179) The Transformation of Athens: Painted Pottery and the Creation of Classical Greece Princeton & Oxford, Princeton University Press.

(2) Dimitros Mathioudakis (2023: 33) ‘ Studio Prokopiou in Leonidas Liolios (ed.) Hyacinth: The Boy is Beautiful no. 3 London. Order from: https://theboyisbeautiful.com/

One thought on “The aesthetics and social culture of the admiration of the male body: discovering that you can say ‘ὁ παῖς καλός [the boy is beautiful]’”