Seeing in person the British Museum’s reconstruction of the elder Michelangelo in Michelangelo: The last decades on July 21st at 12.30 with our dear friend Catherine.

Geoff, Me and Catherine in the sun outside the BFI Café, photograph by Catherine.

Geoff and I met our dear friend Catherine at the café pf the British Film Institute coffee bar where, as is her wont, Catherine persuaded us to a group photograph. I have already blogged in preparation for this visit. That blog can be accessed at this link:

In that blog post, I illustrate how at least two critics of the show make much of its suppression, as they see it of Michelangelo’s concern with the human body and the human male body in particular. Even if you Michelangelo’s male nudes not to have a component of sexual desire, most still agree that they inevitably invite responses that simulate what the eighteenth century art theoretician, Winckelmann, speaking of classical Greek art, called the ‘haptic gaze’. In conversation with Microsoft Bing Copilot, I asked the application how it might extend that concept of Winckelmann’s to how we apprehend the art, particularly of the nude to, because it is relevant Michelangelo’s on the wall of the Sistine Chapel The Last judgement. It replied:

Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s concept of the “haptic gaze” is a fascinating idea in art history. It refers to the way viewers can experience a tactile sensation through visual perception alone. Winckelmann, an 18th-century art historian, believed that the best art could evoke a sense of touch, even when only seen with the eyes.

In the context of Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment, the “haptic gaze” can be particularly relevant. The detailed rendering of muscles, skin, and drapery in the fresco invites viewers to imagine the textures and physicality of the figures. The dynamic poses and the intense expressions further enhance this tactile illusion, making the viewer feel as though they could reach out and touch the depicted forms.

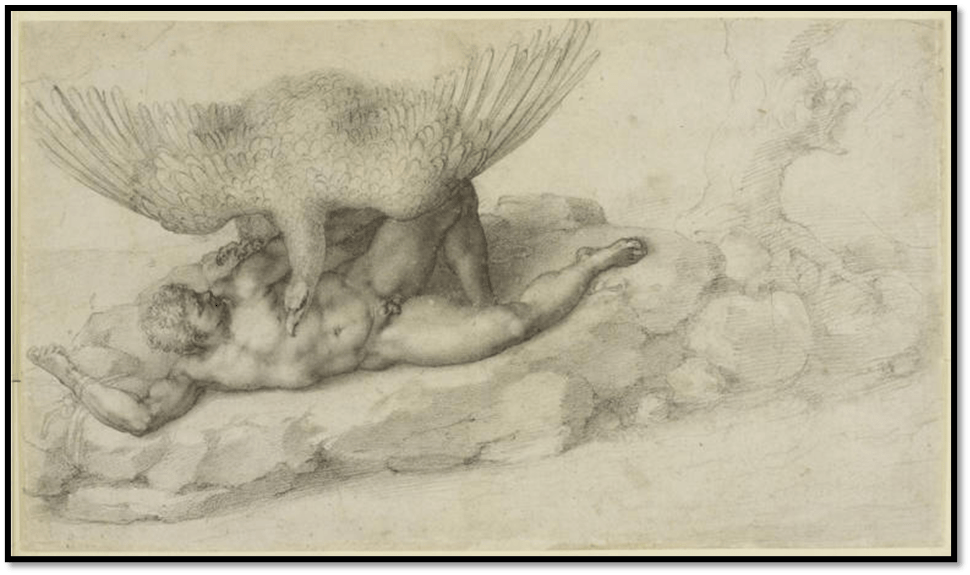

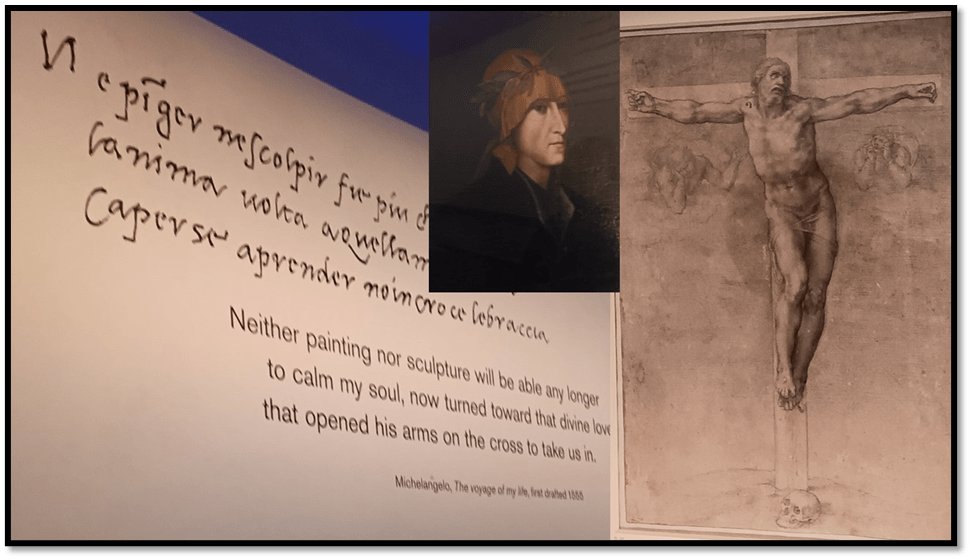

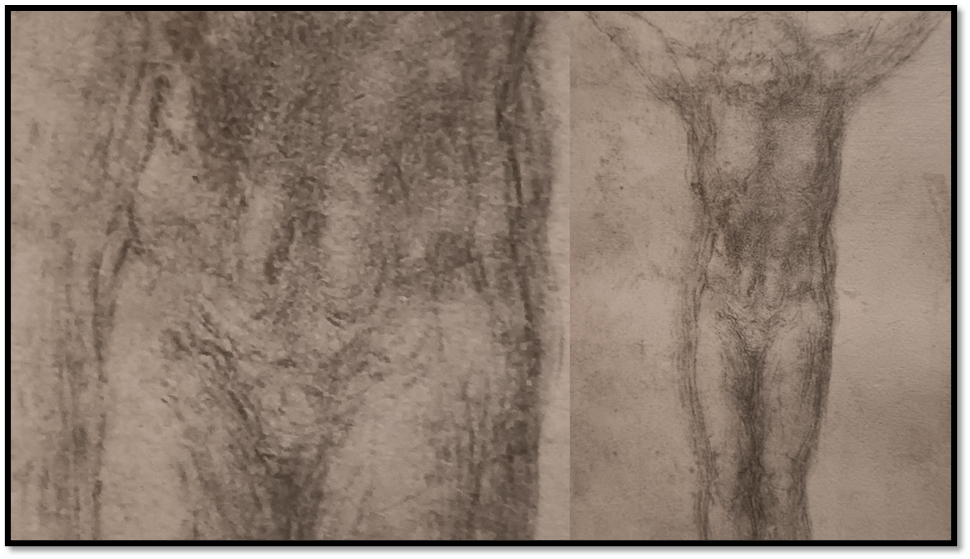

So much for the AI response. In my original blog I cited Eddy Frankel in Time Out asking why the British Museum could not bring itself to be more open about Michelangelo’s evocation of the desire to touch of male bodies, chastising the curators for an apparent approach he describes as: “just awkwardly nudge-nudge wink-winking at it with these adoring letters and chalk nudes, rather than giving it a big celebratory exploration, which makes it all feel a bit too dark and secret to feel like a positive thing”.[1] As I also said – all this at greater length there – Jonathan Jones (whose book on the sexualities implied of Renaissance art is available to buy in the exhibition bookshop I noticed) amplifies this critique considerably, accusing curators of, or so it seems to me, misrepresenting Michelangelo, as he describes that part of the exhibition dealing with the artist’s relationship to (in Frankel’s words again) ‘Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, a young nobleman he met when summoned to Rome to paint the ‘Last Judgement’ in the Sistine Chapel’. Here is Jones of the artwork displayed to illustrate the artist’s gifts to Tomasso, which I represent in collage below together with the citation that so offends Jones. The emphases are mine:

…. anyone can see it’s infused with desire.

Above it is a wall text selectively and misleadingly quoting one of Michelangelo’s letters to Tommaso. He tells Tommaso he is no more likely to forget his name than he is likely to forget to eat food: then a “dot dot dot” covers a crucial cut. What the ellipsis misses out is Michelangelo telling Tommaso he means more to him than food because while it only sustains his body, his beloved nurtures “both body and soul”.

Body and soul. You cannot have Michelangelo’s soul without his body. Take away the body from Michelangelo and you deaden him. It doesn’t even take on the Neoplatonist ideas that shape his drawings. According to these, the love of beauty can lead the soul upwards to heaven: they allowed Michelangelo to show men embracing and kissing in The Last Judgment itself, visible here in this show when you look hard enough at a print of it.

It would appear that the selecting and summarising intelligence of AI in Bing Copilot backs this up, and certainly that wall of the Sistine Chapel bears out the truth of what Jones says, though not necessarily his strident interpretation of it, though I share the same desire as Jones in this respect.

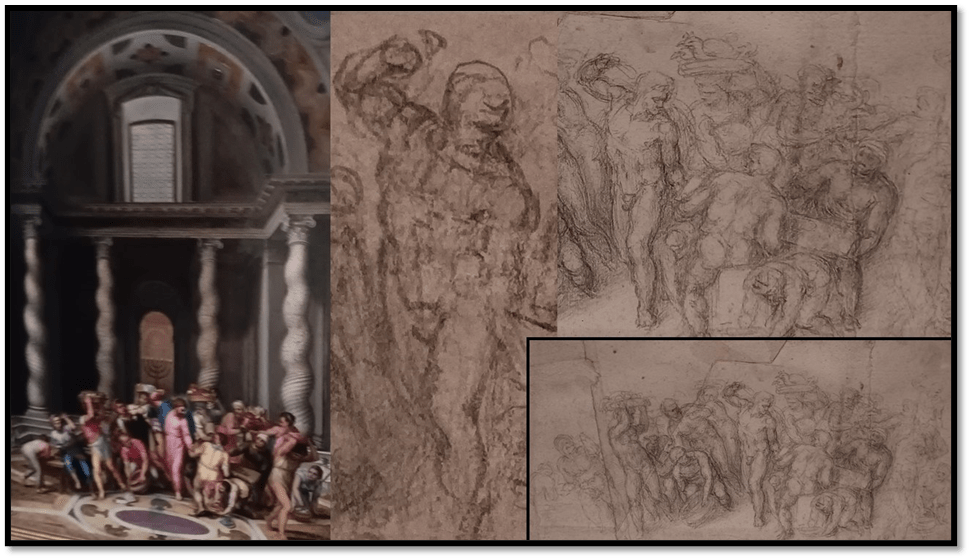

In the exhibition, one sees an audio-visual show that collages together slides of the fresco, showing different partial views, some in great detail, of The Last Judgement, the images showing in a repeated time-loop, whose effect I try to show inadequately below in a still collage.

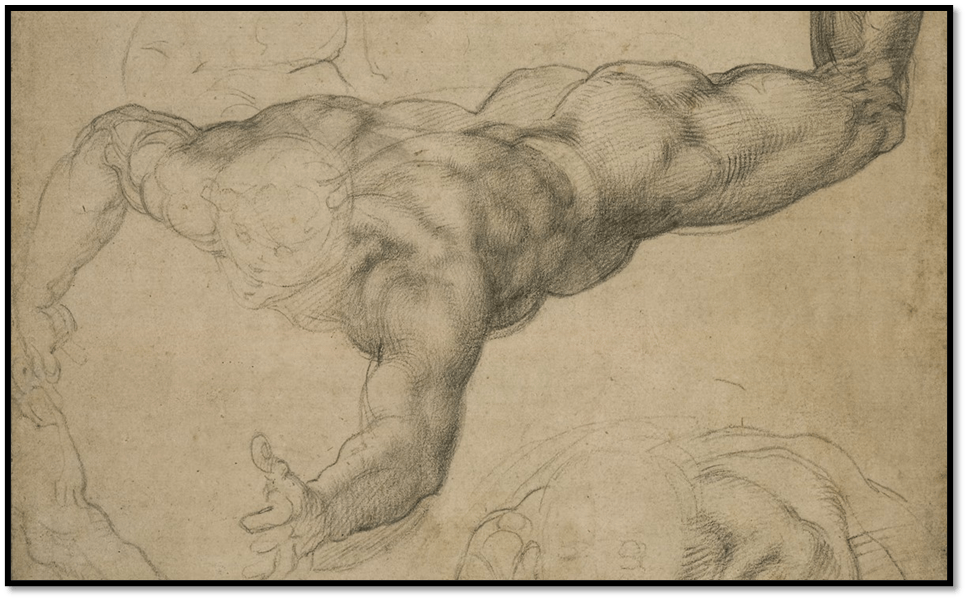

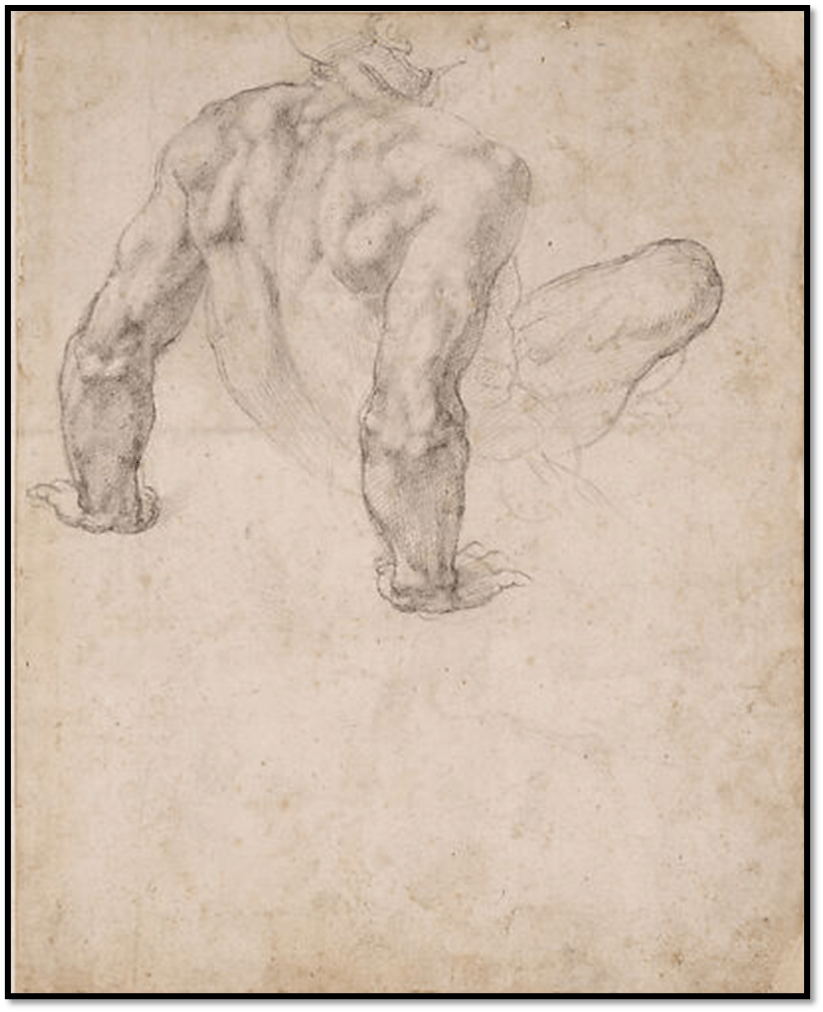

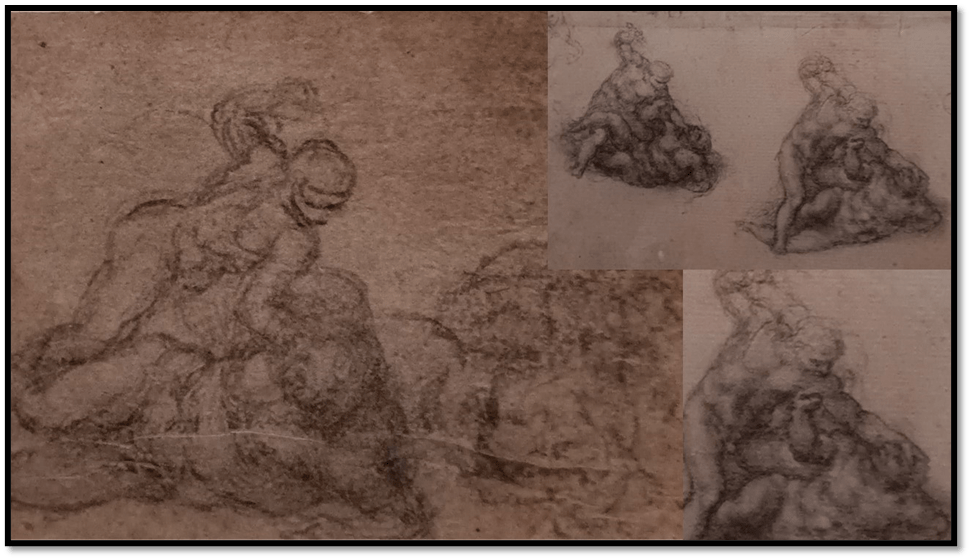

The original works that surround this piece are studies (sketches and drawings) of elements of that work whilst it was in preparation and design. They emphasise the care that Michelangelo took in imaging the male body as a solid thing that yet could be abstracted by the elements of abstraction required by the subject, where however muscular, voluminous and even dense the body-stuff captured (together with the sense of its normative weight under gravity.

Such bodies could seem to be enabled in their representation to never stop seeming absolutely solid and weighted in density and volume but still seem capable of rising and falling in a manner that is like flight or a fall under conditions slowed down by a different mode of ‘gravity’: that it embodies as a supernatural meaning impelled upon and within the body of the divine judgements that decided who of them should rise again ()from the ground, or into the air) and who should fall (to another damnation) that are being made by God and His Son.

In particular, the picture of the man beginning to slowly rise from real or spiritual death into the moment where the dead are resurrected forces us to feel the weight of body he pressed down through his hands to make him rise, and the strain in the torso of the man that knows somatically that it can take this strain and will later rise to paradise. A lovely friend of mine said of this picture when I sent it by WhatsApp: “it’s like your eyes are caressing his gorgeous skin”. The effects are those of varied tone and varied thickness of line or its compounding of many marks rather than one in some cases. The contouring demands that the eye touch the concave and obvious troughs, valleys and ridges to feel their illusionary solidity. When lines or marks fail ort fade the imagination takes over an fleshes out was absent.

Michelangelo’s Study of a Man Rising (1534-6): ‘a metaphor for creation itself’. Photograph: © Trustees of the British Museum

Of course, it is likely some will see none of this or accuse both me and my lovely friend of queering the subject in ways entirely subjective, rooted in our own queer desires rather than that of Michelangelo, for Tomasso, or any other man. But I think this objection rather obtuse, for the category gay man, different in essence from other men, was not available to Michelangelo. Instead, what was available was a sense that beauty was a thing appreciable in both sacred and profane ways, and that this binary rather than that of male and female, or queer or straight had that binary been available, was what was at stake when evaluating the desire that was intrinsically triggered by beauty, erotic in its profane form, spiritually yearning for the body of Christ in the sacred forms. A language of the erotic applicable to both which is how the age could reconcile itself to The Song of Solomon and its erotic longings as allegories of the passionate longing for salvation.

That we all desire the beautiful is a trope of the refined classically educated intelligentsia, and in Michelangelo’s belief system male beauty was the ideal of beauty. The queer art historian, Christopher Reed, says in Art and Homosexuality: A History of Ideas that Michelangelo ‘followed Greek philosophers in arguing that male bodies exemplified perfect mathematical proportions, and thus were more beautiful than the bodies of women’.[2] However, that did not mean his sexual preference was directed at men predominantly even if it was. The desire for perfection was true of all men in the period (it was, as they say, a trope of the refined soul that sought to emulate that beauty in the body and love and desire it as is proper.

Again as Reed says some men notoriously made a virtue of sexual freedom and gained a reputation for a love of ‘boys and beardless youths”, as in the sobriquet-bearing Gianantonio Bazzi (1474 – 1549) (self-promoted as “Il Sodoma” – the Sodomite) and Benevenuto Cellini (1500 – 71).[3] But this potential was already implicit in the idealisation of male beauty – to the point that it was recognised as a matter requiring regulation by church and state – but only under the known temptation to sodomy that was recognised publicly. This is for Reed the case evident in Michelangelo’s exchange of letters with Tomasso when he sent him the letter excerpted on the wall of our exhibition. The pictures including an eagle partaking of the body of a Ganymede (not in the exhibition) as well as the drawing that is. Reed says that codes related to a relationship between an older and younger man in passionate love were apparent but that letters between the pair:

… record the artist’s ambivalence about titling the drawings explicitly and the recipient’s reluctance to display the first of these two drawings. Suggesting that the sexual implications of these motifs were on their minds.[4]

I hope the point is clear. The pictures were fine as long as they did not code the obvious existence of physical desire, whilst at the same time we see that both men saw that in them and regarded it dangerous for others to know that these were not just allegorical expressions of desire alone. It was a matter of fact to them that their desire for each other was legitimate and like that of God, but that it was shameful to profane it, tough profane it most believers inevitably did, for that too was human.

This is the equivalent of queering the norm as we see it today though not of turning the whole matter into a question of identity. As Reed says, we can still miss the point if we try to see people and relationships of the Italian renaissance in the same ideological frame as that of contemporary people and relationships. Given that I think Frankel still is correct to expect more celebration of Michelangelo’s physical-aesthetic love and desire of men, though Jones is wrong to expect the British Museum to underline all the time the presence of desire, if viewers cannot see it for themselves in the drawings.

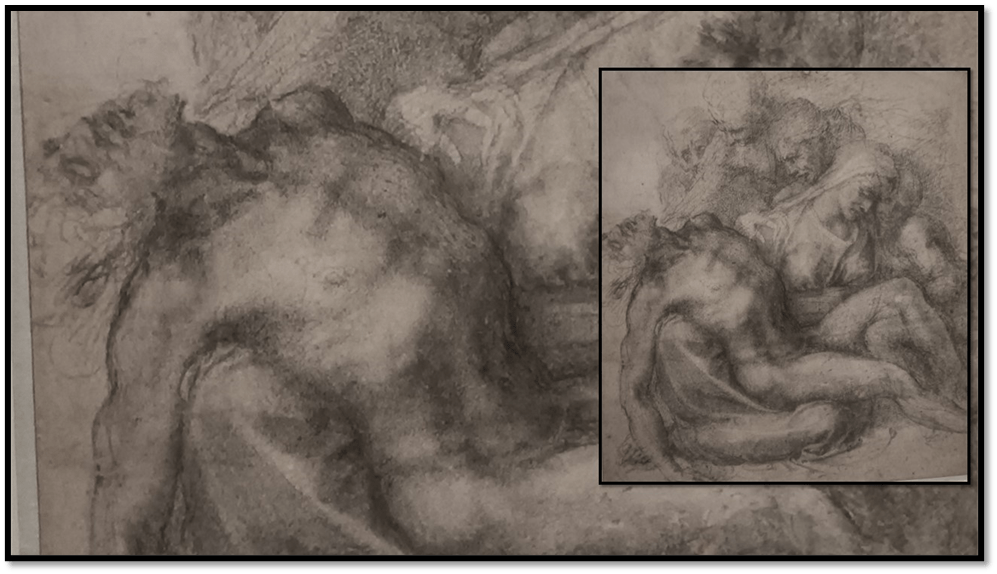

Take these preparatory sketches (below). I have always thought that they some of the drawings of prone men – men for a moment on the ground and fighting to rise again inappropriately labelled as beautiful or sexual. There are too much insistence on the volume and weight of flesh to allow for us to focus mainly on beauty or sex. Even the insistence on the small perfectly-formed penis in asexual relaxation seems part of this. Michelangelo concentrates most on how this organ lies on the flesh just as he does on the spread of flesh in the act of being lain on the ground, but with a body torsion trying to lift its weight, or, as here, being aided to hold to its weight. The right leg of the figure has its muscle and flesh in relaxed state in a way that is shown, as it would be in the reality, as ungainly and sagging in volume compared to the tension in the opposed leg trying to resist the pull of gravity to the ground and aiding muscularly the twist into rising from its prone position. It is all torsion, all dynamism; all about the opposed forces of falling and rising.

Likewise his sketched male heads seem intent on capturing the direction of attention and feeling and resisting awareness of how they look. The faces have the frank expression of Roman rather than Greek classical busts, intent on individual meaning and how this is captured in how the head turns its focus on objects of its interest, rather than in displaying facial beauty, which in these cases is not that of an ideal but of something felt and cognitively and emotionally intended in its expression as its body, presumably acts.

When faces cannot be seen, it is often because Michelangelo is creating drawings that capture the intention and emotion of an interaction as in these preparatory ones of male violence enacted on other men, actually studies of David slaying Goliath).

What I sense is the way in which, when Michelangelo draws, he uses multiple and insistent marks to show motion and dynamism as the meaning of a momentarily stilled gesture. Though the figures cannot move nor be truly three-dimensional, the illusion of both of these is captured in a multiplied number of lines, occasionally thickening into one bolder line, but otherwise suggesting muscular fluidity rather than fixed tension. In one of these,(bottom left) that attentional focus seems concentrated on the meeting of the gaze between the men; the prone one pleading, the one on top suddenly (I feel at least) forced to retreat -even if momentarily – from the onslaught of the violence in its fist. As detail enters the picture the blurred lines of a moving torso do not detract from the artist’s insistence that we know how the penis rests in such a stance. It is all about the body felt as volume, density, weight and the lightening of those things in action and interaction. This man sees beauty in male bodies that is not asexual but is about how desire has been transformed into something other but is still a wonderful moment of bodily expressive capacity.

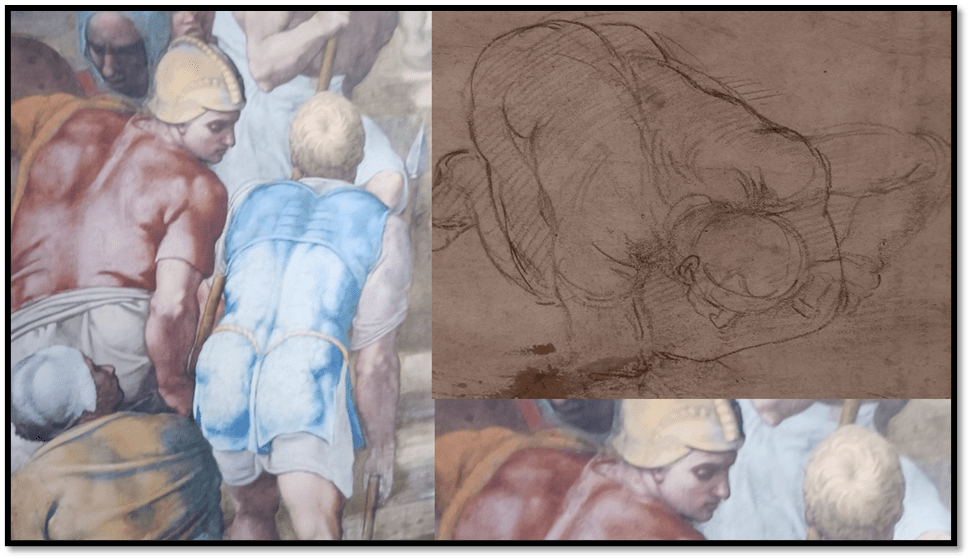

That this expressive capacity can include moments in appreciation of each other’s bodies that tends to the profane is admitted by Michelangelo in a wonderful detail from the painting, shown in facsimile in the exhibition of the Crucifixion (upside down) of St. Peter, where one beautifully muscled and tense back of a worker digging the hole and raising the cross (we see the strain in his torso) turns his attention to the beautiful posterior of a younger male worker alongside him. The gaze of the former draws the viewer’s attention to that moulded posterior> is it appreciative or sexual? Does it matter to determine that truth for soon both must be equally transformed to their task, lowering the weight of Peter on the Cross into the hole dug for it and filling it. As my collage emphasises, it reminds us that for Michelangelo drawing often seems justified by the fact that anyone using his designs must position thee posterior in order to be seen, as in the drawing of the man bending in prostration in the same collage of mine below.

The fact that Michelangelo when older often provided designs for paintings executed by lesser artists like Ascanio Condivi and Marcello Venusti is an issue in this exhibition and Jones is obviously correct to draw attention to the fact that the paintings disappoint. However, seeing them together helps us to define better the specialty involved in drawing for Michelangelo which is not just about the disegno involved in showing interactions between bodies. It is commonplace to point out that such designs used naked figures that need to be so in order to pose them in anatomical correctness for the painter who will draw them clothed, as they would be expected to be in the scene drawn.

But Michelangelo’s nude designs seem as I looked at them to glory in nakedness, and yet again it matters to Michelangelo how the penis of the Christ figure would lie in relation to the tensions of his angry, and uncharacteristically violent body, in the episode of the Cleansing of the Temple (see my collage below). Venusti accurately copies the way in which Christ’s torsion of verticality is even more centres by the falling away around him of the merchants in the Temple, trying to sell trinkets extortionately to Jewish worshippers, though Venusti’s figures seem unbalanced where Michelangelo’s do not, for they twist away in the glory made possible by the musculature structure of bodies without losing balance in the drawings. In Venusti, they seem about to topple. Everything in the drawings emphasises the quality of bone, muscle and flesh structure that is intrinsic to the contest between spiritual principle and their absence in commodity exchanges. It must be expressed in the solidity of male bodies, and even in the preferencing of the absolute size of Christ’s resting phallus compared to that of the other prominent body on the left, a figure added to the group between phases of drawing studies by Michelangelo. There is considerable loss of meaning in Venusti, but you can only know by careful looking not by dismissive comparison as Jones does.

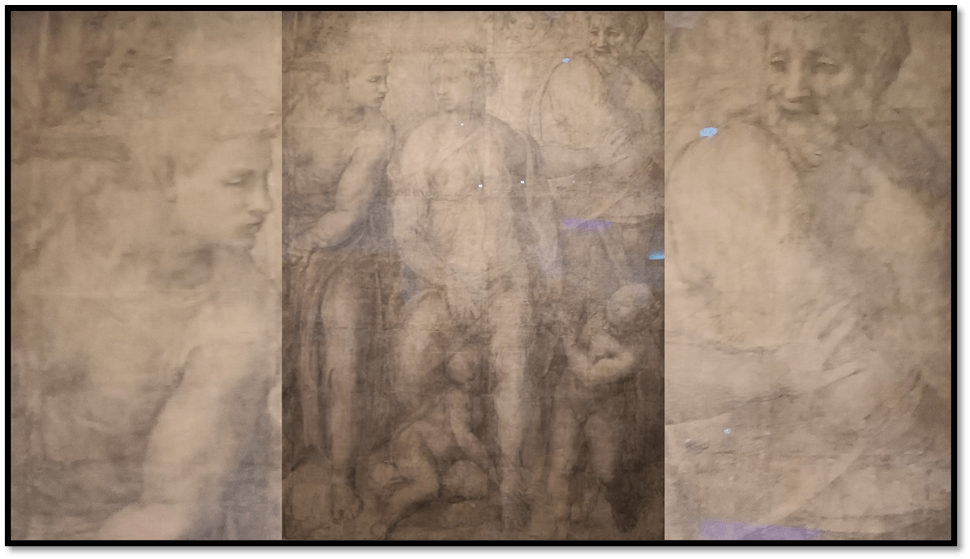

There was much I do not feel it fair to comment upon. Like Jones’ I was bored by the architectural and object design drawings, however wonderful they are in probability to someone who knows how to look. Worse, the crowding of people around the Epifania was such that I gave up. It requires too much attention to discern both its method in a collage of detailed designs and the meaning of the beauty it intended to show as epiphany. Let it rest that the focus of the drawing is in the tripartite gazing that seems to deflect from the reductive effect of the conventional and hackneyed iconic mnemonic at the base of the actual Crucifixion to come. Much meaning and beauty of this piece goes into the relative stance of figures and their living gaze at each other compared to the almost deadly reclining mode of the Christ child.

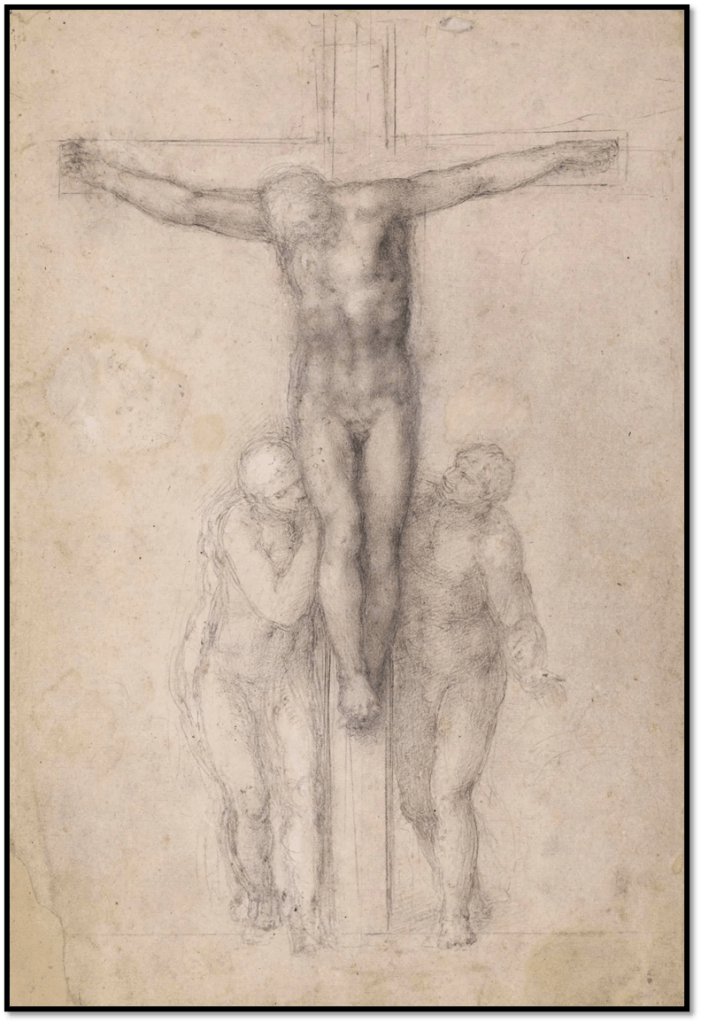

The final darkened room of reflective drawing that the curators argue were not intended for public gaze but for the artist’s devotions are important and I loved that room. If we compare it to the public statements of devotion related to his relationship to the saintly Vittoria Colonna, there is much to reflect upon, as Jones should have reflected on the body soul and the function of the gaze upon icons.

The Crucifixion in the collage above has public and iconic function, perhaps reflected in that conventionalising skull at the base of the cross, and although Michelangelo seems true to the drawing of flesh, the pose and fall of the flesh are not that of deep reflection on the body in pain except in the ideas conveyed through divines like Colonna. I feel much the same about his Annunciation even in drawing, where unusually his designs are clothed, as if anatomy no longer mattered.

In the private drawings, anatomy and pain in the body, even its involuntary reflexes, matter, as in the beautiful Warwick Pietà. Seeing the original did not change my mind about it from what it was in my preparatory blog, but made me look again at the techniques of drawing that attended to detail, There may be iconographic reasons that the detail of Mary’s nipple is made so prominent but iconography is an insufficient explanation in a drawing meant to be for private reflection. The texts on the wall and the catalogue keep excusing the blurring of Michelangelo’s lines as attributed to failing physical eyesight and surety of hand, but the effects are only different in relation to the icon I collaged earlier with Colonna. Here the multiple lines and hatching make you again feel the flesh as if by touch as you look and to sense the weight of limbs dispersed amongst the limbs of others as opposed to those that touch the ground. The unfinished ankles seem to supply the feet we cannot see and at the same time deny them, so that the figure is ungrounded mainly except or its weight on the resisting flesh of the Mother.

The later Crucifixions are harrowing and no longer simply iconic. They show the pressure of lips on flesh, even dying flesh. The flesh hangs with its weight rather than resisting it with taut living muscle, and the multiple lines suggest to me not the trembling of an old artist’s hands but the desire of the flesh to live and of the viewer to help make it do that. The same beauty of tension here is idealised but it is also a nakedness that seeks cover.

Recently in a blog I quoted John Berger on this (see the blog at this link). This is how I summarise Berger’s thoughts about nakedness there:

Berger asks McBurney to throw out of his head ideas of the simple ‘innocence’ in nakedness: nakedness is, and always must be associated with desire. But his understanding of that is nuanced. We desire the naked he says in order to ‘cover’ its recklessness and lack of disguise, its ‘bleakness’ with our response to it. It is essentially a mnemonic of the ‘human condition’.

Seeing a naked body of any age or either sex, we remember our own, and the contact of our own from birth onwards with other bodies. Such contacts were tactile: they involved touching and being touched. They were also metaphoric for they were a demonstration of the similitude of all human bodies. … It is where empathy begins. It is how one can put oneself in somebody else’s place in the gully, for example, five thousand years ago.[5]

There could not be a clearer reading of the Pietà than this, even though it was far from attempting to be a reading of that drawing. Even the manner of the child lying in his mother’s lap, the invitation to the nipple, the need to touch the flesh and cover it with our desire. It is a long way from the exploitation of mother-child relationships that Chrostopher Reed dismisses, together with its baggage from the early Freud of giving a definitive mother-based aetiology of ‘homosexuality’, rather it raises the issue that nakedness is the mnemonic of a proximity lost but available to us in both times of vulnerability and desire, and hinting that these things have more in common than we like to think.

And the final piece from the Reflections section of the show was perhaps my favourite exemplum of the worship of the body and soul of a man expressed in Michelangelo’s black chalk marks. It is known as Christ on the Cross and is simply that with no other figures mediating our response to the flesh in agony but also in supreme beauty. Again the British Museum plague sees it as the crude work of a man unable to hold a piece of chalk steadily and unable to see properly whether he has done so or noy. But contemplate this as the artist did when he made his marks and what do we see?. I can only say that which I see.

What I see is chalk whether dabbed or rubbed creating flesh that is felt in its ridges of soft flesh and sulci. The focus on Jesus’ groin becomes a series of mysterious marks indicating volume but not shape but lying triumphantly below the central ridge of the torso. The lines indicating the margins of three-dimensions of outer flesh quiver not with the inaccuracies of their making hand in my view but rather of its contemplative desire feeling its way between the spirit and body of the beloved divine made flesh. Even Jesus’ hanging head points us down to that divine torso, offered up and taken, even eaten, in the name of God. The catalogue gives a judgement I find quite beautiful and could be the curators’ riposte to Jonathan Jones, that they know very well and there is no spirit in Michelangelo’s work without showing his ardent desire of the body. It is desire which creates the liminality of the supernatural, whether that be being absorbed in God’s flesh or taken up in spirit – for these late drawings show the cusp between both possibilities, wide in its very trembling intensity. They say: ‘These evocative Christs appear to be the expressions of an effort to represent a body in transition from the temporal to the spiritual world, transcending the physical laws that rule the denser bodies of physical mortals’. [6]

My view differs from the curators only in not sharing with them (perhaps) and Michelangelo (certainly) a belief in the redemptive power of the embodied Christ. For me love is already the spiritual, or numinous at least, that enters the space between the cusp of flesh as grass and flesh as a divine concept, which I am ready to hear explained by those who sense a mystery still remains for explanation, such as John Berger.

By all means see this exhibition, but beware the tension caused by crowding around items too small to be examinable in crowds but anyway, feel tempted by the book by Sarah Vowles and Grant Lewis. Its reproductions are almost good enough but never fully. Fortunately, the crowds are lesser in the Reflections final section where it matters most for there are no blatant audio-visuals and there is a kind of contemplative quiet produced. So go – do. It is worth it.

With all my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Eddy Frankel (2024) ‘review’ in Time Out (Tuesday 30 April 2024) available at: https://www.timeout.com/london/art/michelangelo-the-last-decades

[2] Christopher Reed (2011: 47) Art and Homosexuality: A History of Ideas Oxford, Oxford University Press

[3] Ibid: 45

[4] Ibid: 51

[5] John Berger (2024: 167f.) ‘Notes for Mnemonic’ in Tim Bell and Simon McBurney (curators) & Russell Warren-Fisher (book design) [2024: 7] Complicité: Mnemonic [A Site], Colophon, 167f. All in my blog at: https://livesteven.com/2024/07/12/this-blog-is-about-eventually-seeing-mnemonic-for-myself-in-the-olivier-theatre-at-7-30-p-m-10th-july-2024/

[6] Sarah Vowles & Grant Lewis (2024: 218) Michelangelo: the last decades London, The British Museum Press

4 thoughts on “Seeing in person the British Museum’s reconstruction of the elder Michelangelo in ‘Michelangelo: The last decades’ on July 21st at 12.30 with our dear friend Catherine.”