‘This is not quite what I remembered’, says Susannah Clapp, the theatre critic of The Observer of mnemonic at the National Theatre who had also seen the original production.[1] Clearly she could not have said this had she read with understanding Simon Burney’s fragment discussing the genesis of this ‘revival’ in Complicité: Mnemonic [A Site], a book curated by Tim Bell and Simon McBurney (available at this link) and beautifully designed Russell Warren-Fisher. Neither could she have listened in the theatre for these words are in there too. In the text IThe site of memory is not a place. It is an event. Each time you remember you have to make that memory. … But the memory is different each time’.[2]The site of memory is not a place. It is an event. Each time you remember you have to make that memory. … But the memory is different each time’.[2] This blog is about eventually seeing the play for myself in the Olivier Theatre at 7.30 p.m. 10th July 2024.

Above is the moment as Geoff, my husband and myself awaited o enter the Stalls entrance to the Olivier Theatre. How unreal feels the transition from outside a known building to the interior in which an i imagined reality will be performed. I think that feeling may be relevant. This blog is a response to preparing for and seeing mnemonic written on and the day after seeing the revival. It follows and refers to an earlier preparatory blog posted on May 7, 2024 (available at this link).

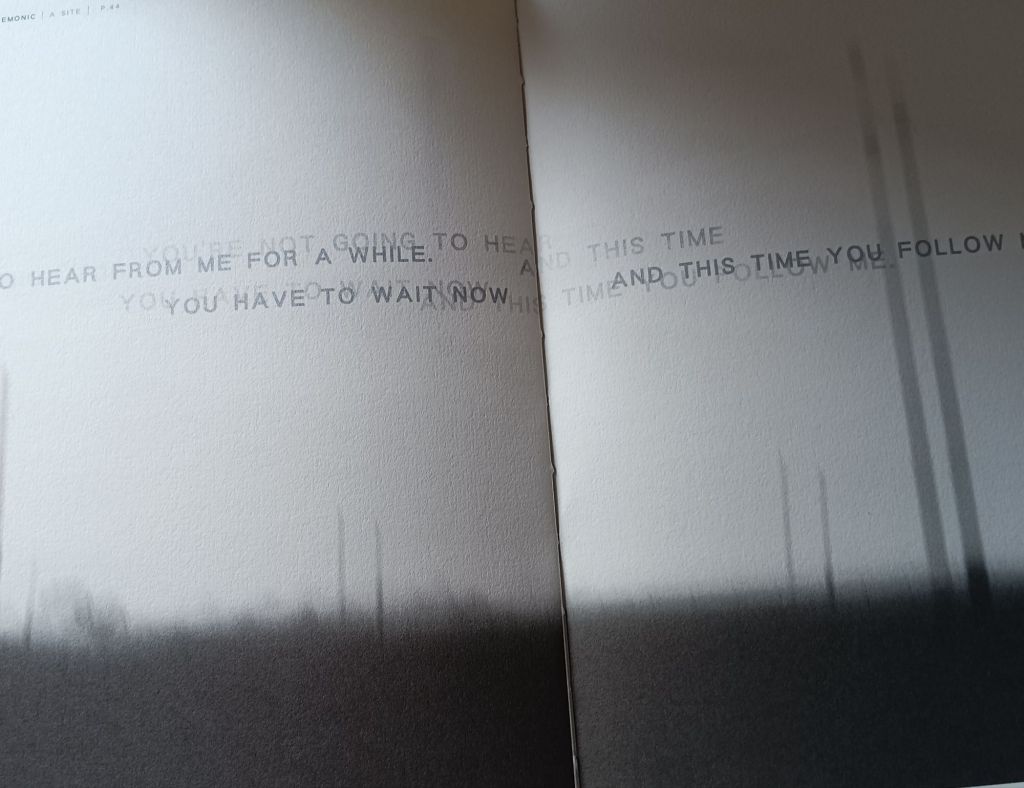

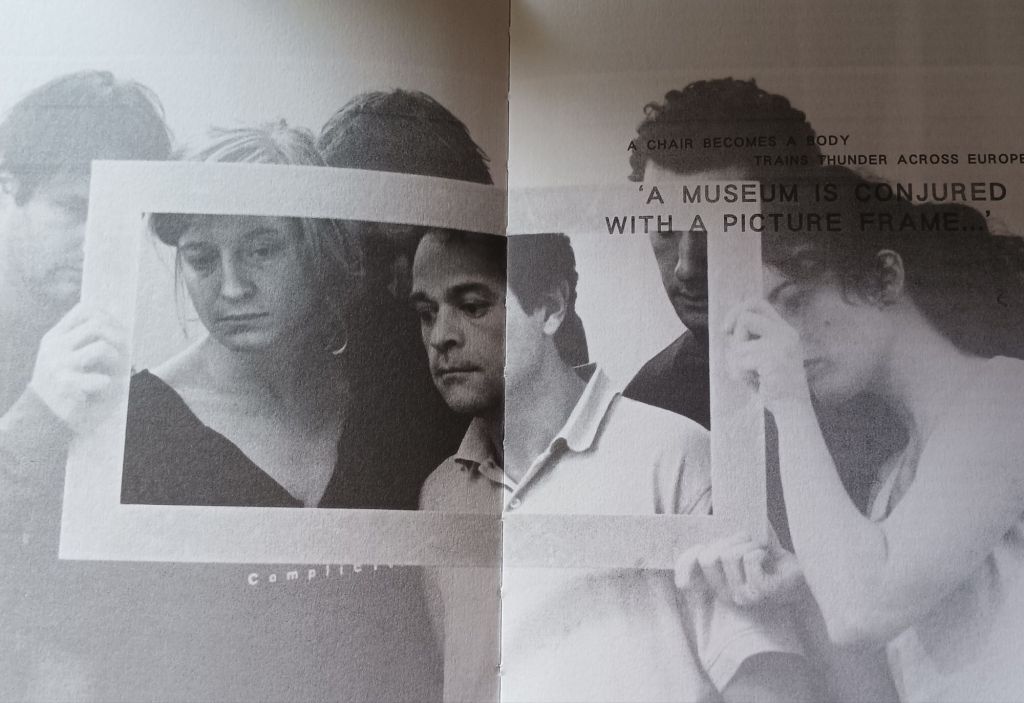

I started writing this before we went out to the play tonight and having read the brilliant book, Complicité: Mnemonic [A Site]. It is a collaborative book operating metaphorically as a palimpsest (a document written upon and over the impression of another legible or less than legible document). Much of the book’s graphic and typographic work employs doubling effects with text and images or both, in which typing of words appears over another typing, sometimes of the same words (and hence the doubling (or tripling) effects). As well as other over-writing, like the use of ‘manuscript’ notes or highlights there are double-exposed photographs, sometimes of the same image, as well as comparisons of photographs between different productions of the ‘same’ play (which can never be the same event or a particular re-call of each of those events but necessarily ‘different’) by Complicité (1999, 2001, 2002, 2003 & 2024).

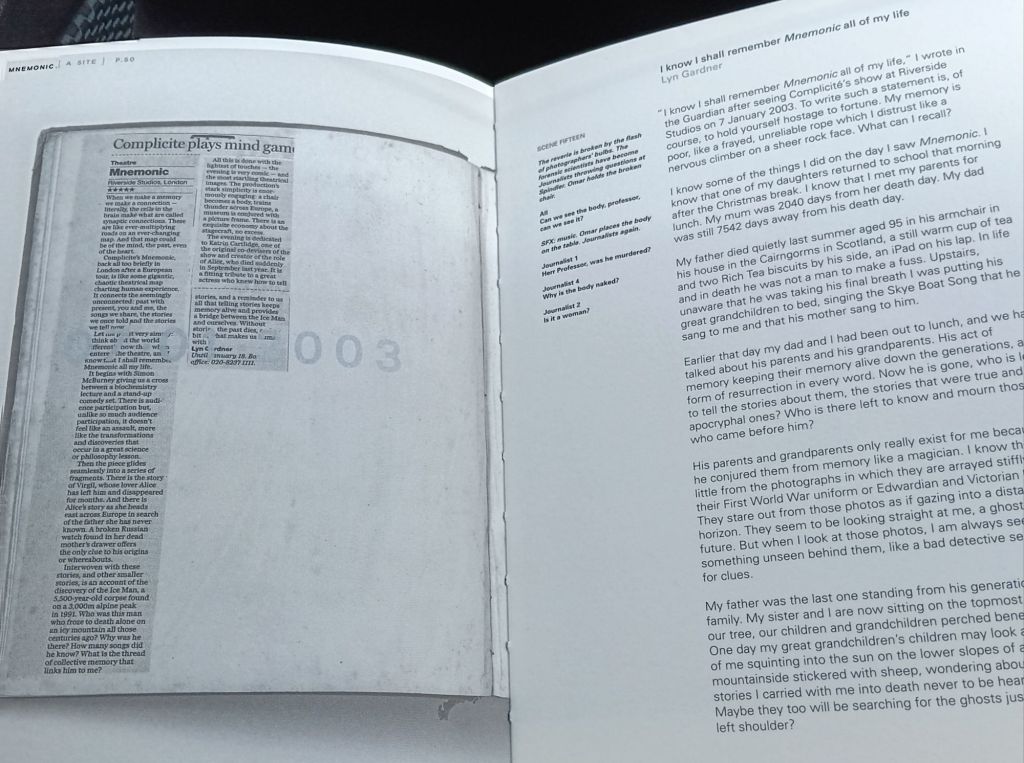

The book contains short pieces of writing by past, present or both theatre members in the play’s production, direction and sound design as well as its past critics. One such critic, whose article on the 2002 production I cited in my last blog and which is reprinted as a graphic together with her reflections on it in the companion book referenced above. There are also other writers, and theatre artists, and the cast of actors past and present, including one who died tragically at 40. There too are advisory and collaborative staff (a mathematician, a neuroscientist, an archaeologist and the radical poet and writer, now deceased, John Berger). There are also pieces by earlier version audience members, some of which having become famed in their own right since then like Toby Jones and Frances McDormand. Some have become political activists for reasons implied in issues in the play, particularly the nature of migrations based on imbalances of power between human groups, constructed as competitively different. Not a single contribution in the book is not worth reading, and reading again.

Before starting, I think we need to slay a considerable dragon – the venerable theatre critic of The Observer, Susannah Clapp. In my , cite the rather disturbing opening of her recent review. It is disturbing given the themes and messages of the play. She says: ‘This is not quite what I remembered’. But then would, or even could, it ever have been quite what she ‘remembered’? The whole point of the play is that no memory apparently of the same episode of time and space is ever recreated in the same way, but must be different for it is created new each time. This is in the prologue to the play and beautifully written in the book in the companion book to the play by Simon McBurney, as it is in the programme. The best formulation of the point therefrom is: ‘The site of memory is not a place. It is an event. Each time you remember, you have to make that memory. … But the memory is different each time’. [2]

In Complicité: Mnemonic [A Site], many prior auditors of the original production write testimonials both to the shadows and semblances into which the play had receded in their memorial recall and of how the changes in them and the histories impacting on them including their own biography, had changed the thing it seemed seeing the play was for them in a different time and space to what it was in memory for them now, situated in this new moment in time and space.. such experiences are not intellectual as such, or only intellectual and it us therefore even the more surprising that Clapp says what she says, as if in rebuke of the new production.

A much stronger critic (and artist), Lynn Gatdner, is cited in the companion book already cited to show how her original glowing review (Clapp’s original was as waspish as her new one though you would not guess that from her current words) embarrassed her, for in it she had said how the production was so powerful it would stay with her always. Yet, when asked to contribute to the book, she found her memory of the original full of holes in the detail and with differing resonances of meaning emanating from each aspect her recall. Toby Jones and Frances McDormand, then unknown actors in the audience say similar things about the metamorphosis of the play in its progress through successive memories indifferent time-spaces too on their contributions to that beautiful book.

On top of this different theoreticians of the discernment of patterns in data in mathematics, neuroscience, theatre, and history show why pattern never seems fixed. John Berger’s gift to Simon McBurney, a mat once owned by poet, Mahmoud Darwish, whose beautiful, once more obviously readable, cultural patterns had been changed by the new patterns caused by random exposures to the sum and the bottoms of sitters on it causing wear.

All that richness of perception involved in the creative preparations before the show and between its avatars and in its audiences, those audience members at least concerned with refining their response to creative art as a feature of their own lives rather than writing up their reputations as fearsome theatre critics, is in the text, even the rewritten text for this production and in the companion book (I will call that book [Site] hereafter). Compare this richness with the plodding insistence in Clapp that the textual changes in this version of the play are either unjustified or artistically incompetent (her view is hinted rather than spoken). She reminds us that ‘much dialogue and speech has been reinvented for a new cast’ yet praises only that is as good as it the more obviously derives from the original 1999 production, later adding that ‘this reincarnation is more deliberate, more didactic, more confusing the original’. [1]

I can only say that this is not the view of other audience members during this run to packed audiences at the National, for I, unfortunately, saw the play for the first time here. The script of the new production is not (I am told ‘yet’) available, but it is clear that the reinvention are not explicable only because of the change of cast.

Clapp gives no credence in her review to the socio-cultural content of the play, even though it constantly interacts and sometimes vies with the psychosocial content. She seems to forget that any theatrical production, and not just radically innovative ones like this, interact with history, not only creating new meanings to old words but rendering some redundant.In my old blog, I cited the speech below from the prologue, in the early versions read by McBurney as he is about to enact, in the rest of the play, the role of Virgil, a white middle-class character. The name Virgil references the classical Roman poet, appropriately conveying the mainly Western attitudes and traditions of the central character of mnemonic.

So now we will go further back. To autumn 1991. September. Where are you? Can you remember? It’s just after the Gulf War and before Yugoslavia starts to split again. Perhaps it’s completely empty in your imagination. … Or perhaps there are one or two fragments . . .[8]

In that blog, I said of this speech, predicting my possible response to an unchanged speech: ‘For most in 2024, it is not just because these events are a much longer time ago but that they will have lost significance to a world whose conflicts present differently’. As I recall this speech in the new production, it now references another event, more pertinent to a 2024 audience but still ‘historic’. It references the announcement of the Brexit vote, a shock to many but fighting shy I suppose of the present situation in the Middle East, and especially of the sensitivity in London today with the coexistence of diaspora communities both divided between each other and within themselves, of the representation of the current Gazan genocide, however minor the effect of the reference tot the tenor of the play as a whole.

McBurney directing this production with Khalid beside him, reinventing the latter’s original role (detail from programme)

Yet, as I said in the first blog too, these sensitivities about forced destabilization and enforced migrancy of populations will be even more pressing in a play that deals with, amongst so much else, in my earlier words, ‘Jewish diaspora and the cause of human migration in other contexts’, such as the case of the Iceman 5,500 years ago, another fugitive from social and racial or tribal violence.Of course, there is also a brief reference to Gaza in the play, that accompanied the monologue by the Egyptian diaspora actor, Khalid Abdalla, who also references his earlier roots in Palestine. When this speech was spoken by McBurney, who has never even lived in Scotland despite the names, let alone the Middle East, says Khalid with the playful sense of being one-up on the earlier actor, and now director of this version, in the displacement and migration stakes.

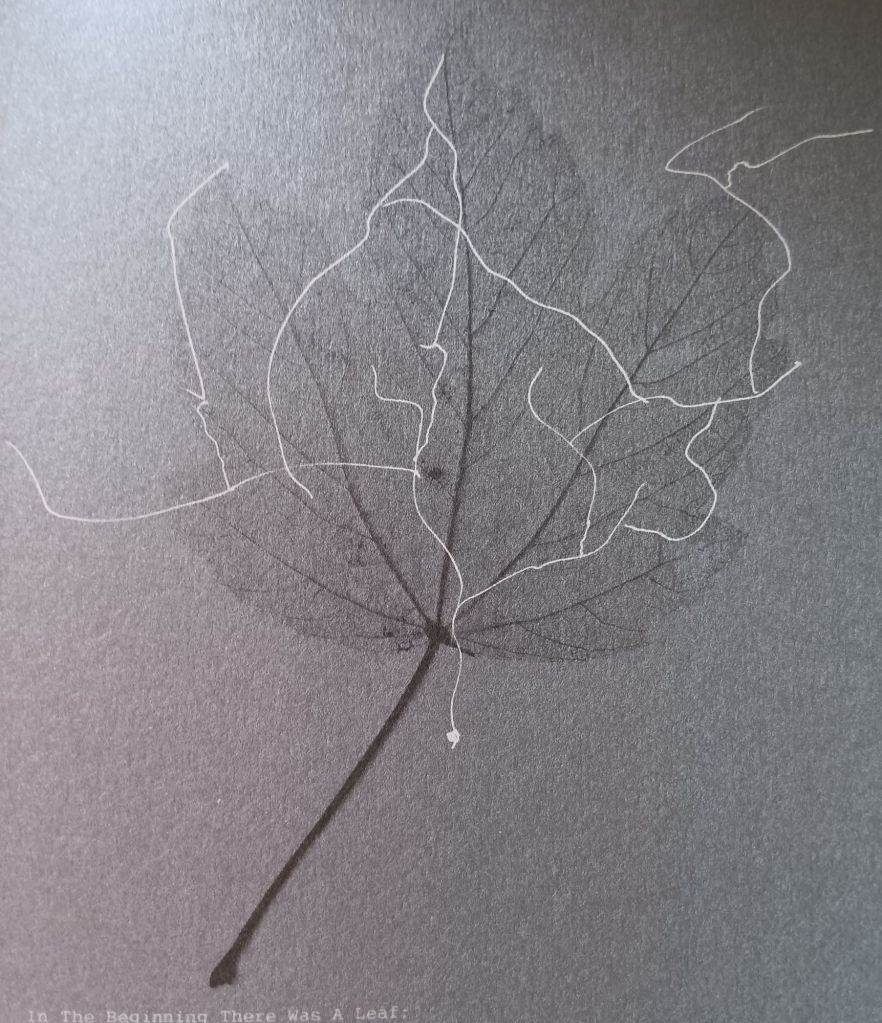

Those changes are then not solely about casting, but are partly about casting, for they animate in body and skin colouration the fact that we are all related somewhere in history by the routes from that original node of some distant beginning at the stalk of an imagined leaf have diverged widely. I refer here of course to a commanding image in the play, where the audience is addressed in the prologue and asked to take a leaf out of a linen bag on their theatre seat )placed there before the show) and to trace its patterns of growing divergence in commonality. The fractal pattern made is beautiful, mathematically precise but looks and feels random. Again Clapp praises Khalid’s interpretative grasp of this piece in the prologue but claims the play does not, we presume unlike the original in her eyes, go on to deliver the ‘investigation of memory’ that follows. But that is surely a failure of imagination in the critic, not in the play.Leaves and complex hard to negotiate fractal patterns matter.

And more than that, the patterns in a leaf, or in the pathway drawing above also resemble the tree structures in neuronal connections, a fact not lost in the play’s early publicity images:

Of course, the script in the bulk of the play reads much the same, and a leaf is still provided to characterise the fractal patterns and numerical growth of points of origin of each person. Khalid, as performed by the same or different Khalid (as Simon was played by the same or different Simon in the original) as he investigates the leaf, with reference to Middle-Eastern heritage many generations back, does not in the play enact the role of Virgil, but the namesake, Omar, presumably a memorial reference to Eastern poetic tradition and to Omar Khayyam.Hence, there is, of necessity, fresh impetus to cultural reading that the white Irish-Lithuanian character, Alice, the girlfriend of a son of an Arab world a long way back, who discovers her probable, but uncertainly established, roots in a lost father she seeks, in the story of a man fleeing Polish pogroms against Jewish settlements, who may or may not be that father. Is it her father? Is she Jewish. Is her homelessness another version of the history of Jewish diaspora. Finally she refuses to seek to know? The stories that lead her to her destination after all, are tainted by self-interest. Thus, the play insists on the question about whether accuracy in knowing our origins would even help place Alice, or anyone else. All of that means that she could be, by birth, in all probability Jewish but that she will never know for sure. And, of course, had the play dared, its reference to Gaza might have been complicated if followed through, and have had to confront the Nakba too as well as the Holocaust. But is not history often matter of unconnected fragments because we refuse the connections as human beings in an over-complex world, and like our empathy relatively shallow.

Eileen Walsh in a detail from a rehearsal photograph by Johan Persson. In the programme.

However, the role of Alice is made even more poignantly liminal in that, in the new production it is played by the brilliant Eileen Walsh, who felt that she was resurrecting (a spooky term like reincarnation indicating a ghost of flesh) the role played originally by Katrin Cartlidge, who died before this revival in her forties. Walsh pays tribute to how Cartlidge had to be researched by her to know how to play Alice correctly, which turned out to mean she must play the role differently. Analogously, Simon McBurney remembers in[Site] that Katrin was always liberating meaning from other people’s obsession with cold facts about the play’s original stories, just as he remembers the phone calls which announced that she was ‘perilously sick’ in the Royal Free Hospital and then that she had died. These meanings too change history and interact with the plays ‘reincarnation’. I think the think I dislike most about Clapp then given the respectful networking in this performance is her ad feminem attack on Walsh who, she claims, ‘operates on default Celtic mournfulness’. This is nonsense but I have heard prejudice that is very similar directed to Irish accents in the English theatre.

How this production deals with migration and origins that lie behind prohibitive boundaries (even the Irish diaspora) is like the original play nevertheless, if the script is to be believed, and also bears its host like an uneasy ‘double’ of itself. These are effects beautifully captured in [Site]. There are doubles created in that book by simple over-typing, a kind of ghosting of words on each other:

Likewise, multiple exposure camera plates and by over-typing. Some mime the effect of looking at a thing through another thing, like the semi-transparent gauze curtain used to destabilize images of human interaction in the film or to mime a scene passing by in a train window, refracted by the window but also blurred by the perception of things that are in the motion of the train:

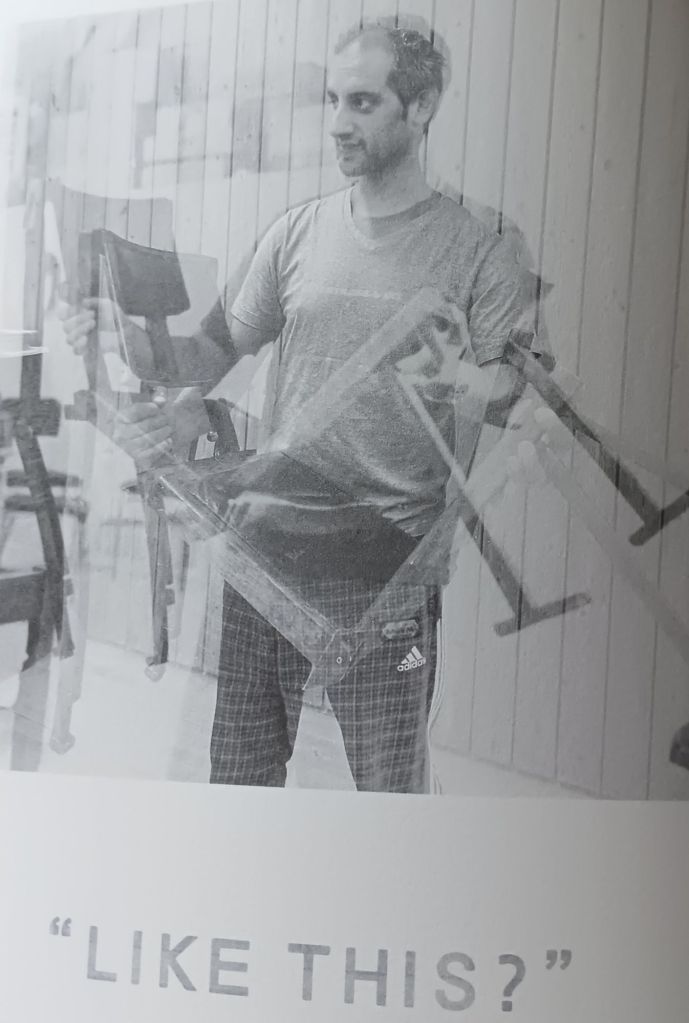

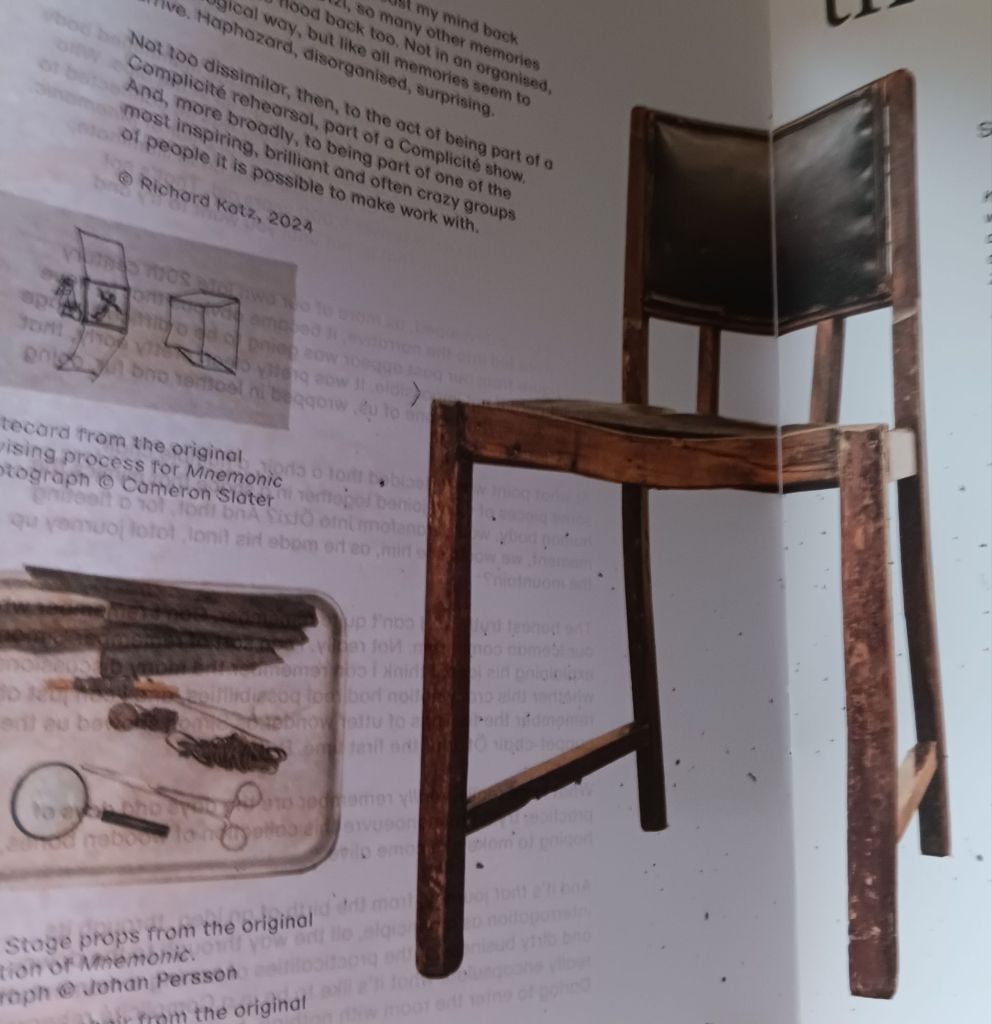

And much in these effects is about how time creates both doubles and the feeling, the classic theme of the doppelgänger, how a thing or person, perhaps even ones#’s self, is identical to its original yet uncannily different, a feeling analysed by Freud in his his essay on The Uncanny. A double-exposure is a trick with time that stamps identity on the non-identical or identical, creating double illusions in each case, as is the palimpsest or over-typing. One of the best examples from [Site] is a series of versions of a picture of Jonathan Katz holding the chair used in all Complicité productions, he tells us, to create an articulated figure that can re-enact Iceman, Ötzi, the name given to the Iceman before, as it were he became Iceman 5, 500 years ago. All this is about doubling, re-multiplied in the mainly exposures of Katz holding the chair in rehearsal. We are told various times that this is the same chair used in the original by Katz.

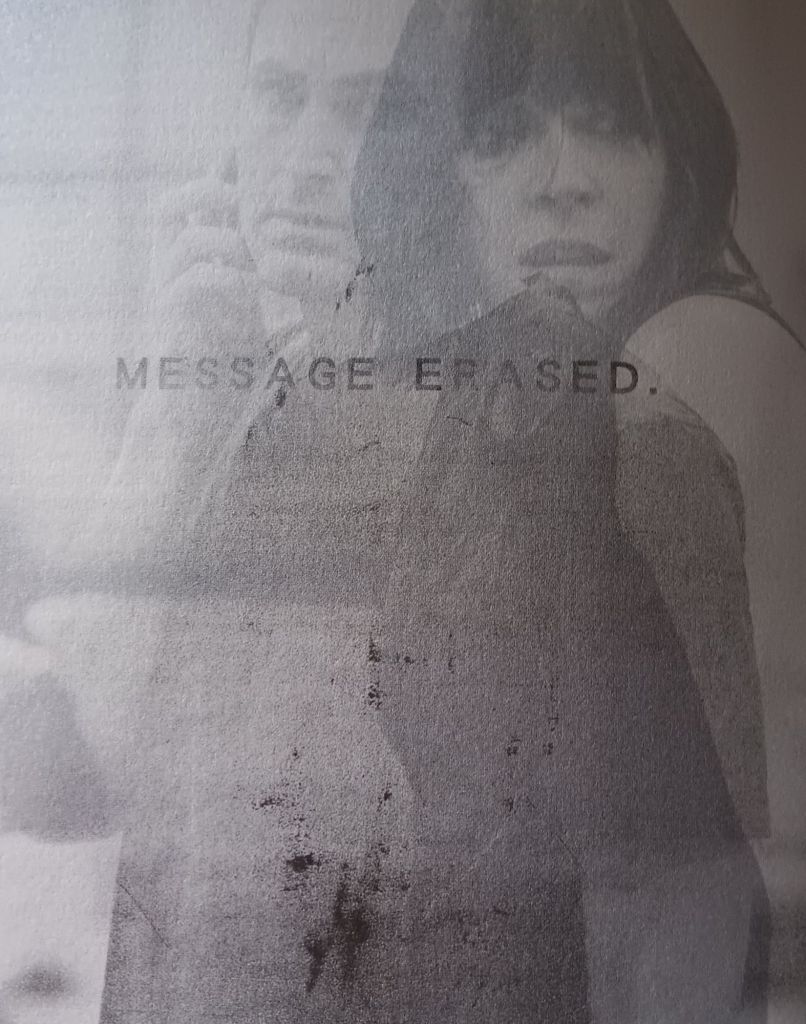

Even text over image is a kind of image, even before the text is doubled on itself. In a captured double exposure of the actors of Omar and Alice, the two persons are exposed each other but the message from the play, also present over, or between in a typeface reading ‘Message Erased’. This is very near the emotional tenor of the play’s meetings that are not meetings and the sens that loss of a person, or their image (or your own self-image) is a kind of semi-erasure.

Fictions, as Alice finds, are sometimes deceptive, including stories of origins. And we don’t have to believe that actors or acting companies use truth all the time, even in saying this chair is the same one as the original. We may even query whether that would matter. There is another chair in the programme which looks very like the chair we see on stage when we enter the theatre. Here it is in the programme. It certainly looks old enough to be the one used in 1999 but not necessarily the one that disassembles in order to be reassembled as a puppet representing Ötzi:

When we see ‘this chair’ (or is it?) on the stage we have noy yet been told by Khalid doubling perhaps as Omar that this is the same chair, according to Simon McBurney from the original production that Omar was not in, but Sion was playing the ‘identical’ part but known as ‘Virgil’. Uncanny doubles proliferate. Yet on the stage all we see – is the massive space diminished to the width of the light a spotlight casts on it in an ’empty space’, the primal definition of theatre by Peter Brook.

My photograph before the production

Watching the play enables us to grasp that even its concern with human migrations and identities that collide in uneasy interactions enables us to see how much of what people try to sell to us as ‘reality’ is a kind of ‘performance’ rather than something substantially real, and not necessarily a pleasant performance, often one we are coerced to play, as Alice feels she is, not unlike the Iceman. The satirical humour I noted in my earlier blog in the part of the script about how ‘experts’ (archaeologists, climatologists, medics and cultural historians) describe socio-cultural human group phenomena like migration doubles in effect when performed for it draws the point that performance is necessitated in supposed truth-telling based on evidence. Genocide though is not funny even when we are invited to laugh at its representation as we are with the Iceman’s story seen from multiple points of view. He is the last remnant of a group reduced to one individual some think, precisely by genocide. The humour used against the dependence placed by an English theorist on an apolitical notion like transhumance to explain all migrations, with no evidence of sheep or goats on record, was brilliant in live production. He typified those, not always English but as blinkered as, who defy openly any reliance on explanations that the Iceman, also known as Ötzi, was seeking asylum from violence.

I have travelled a long way from my point and I will allow Susannah Clapp to drag me back, for none of the changes she identifies in the play can can easily be read as a play that has lost its point in transition, or, as she puts it, reduced it back to ‘the lineaments, not the flesh, of a groundbreaking show’. I, for one but the response of the auditorium proves I and Geoff were not alone, in finding it ‘groundbreaking’ in a way that does not suggest a simulacrum of an original fleshly whole of a play.If it has lost anything, it is in Clapp’s understanding of it. Of course, it is a play about things and identities that get lost in all kinds of transitional phases. Many things get lost in the transitions including and composite with time and shifting imagined space in the play – all brilliantly evoked by animated stage lighting devices representing expeditionary research, flight from oppression, even of a chair transitioning into Ötzi, the Iceman before he became the Iceman, or simple cross-border train journeys: Eurostar and beyond. Alice’s journey, for instance, loses its originating purpose when she disembarks from a train sure that the pursuit of her patriarchal tradition contains many deceptive elements.

Only the reprint of the old text is available as yet from the National Theatre bookshop. There were rumours the new one might later be available. Let’s see.

Moreover, this remains a play about time that interprets time past, present, future and the process of its passin away, along or into other states of consciousness of the world. This production did, as I predicted in the earlier blog ‘anchor its own ‘present’, as the original s did. For those presents are all things changing ‘continuously, as the play ages in theatrical and art history‘.

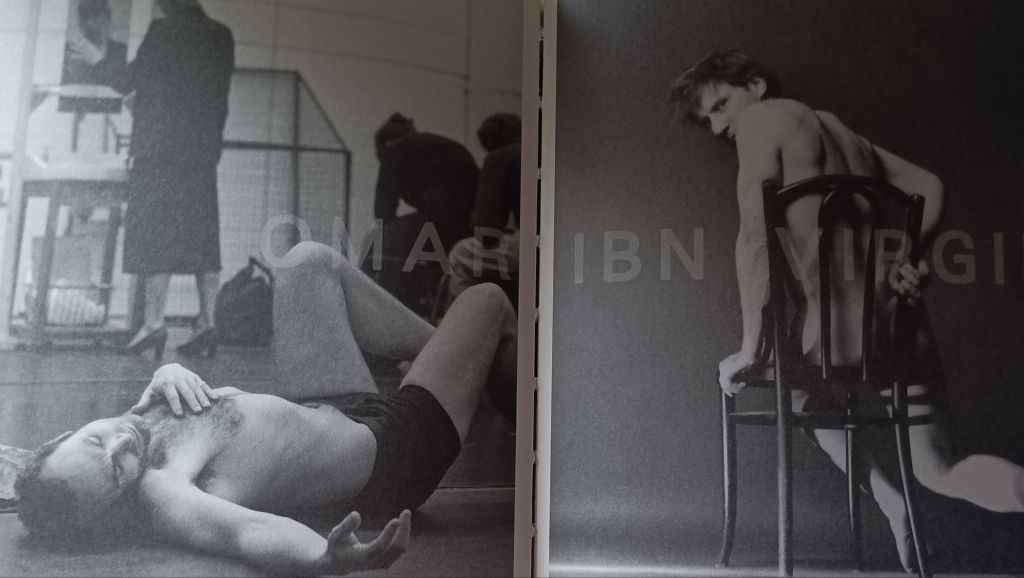

However, a question remains from the preparatory blog. Did this production use the metaphor of the man rendered naked openly and honestly, and make us aware of why and how nudity is justified in theatre? As expected it did, although Khalid plays a different role in some ways to McBurney. Omar still meets his own ‘unaccommodated man’ (naked and cold in a storm of rhetoric around him) playing the Iceman but I think I oversimplified how nudity works in the play in my original blog.

Khalid and Simon bared (almost)

I argued in the first blog that the play text offers nudity is a symbol or emblem of human vulnerability. I took this from an exchange in the play between a German boy, Carlo Capsani, and his piano teacher as he learns the piano. Carlo was a man who was to become a famous mountain climber whom, it was presumed died, his body never found, in the ice like the Iceman. The teacher says to the boy that to play well he must expose himself, as if naked, feelings his vulnerabilities. I can forgive myself for my extrapolation if I stop there. But in production what emerges is that the piano teacher dares the boy to imagine themselves as both naked and scaling a glacier, lost in joy. Suddenly an image of ‘vulnerability’ becomes one of desire, with elements of danger as well as purity embedded.

Why? Because we feel naked. And what does nakedness remind us of? It reminds us that our fears are natural, that we are all vulnerable. So, let us agree that we are both frightened, stark naked and that we climb this mountain together.[10]

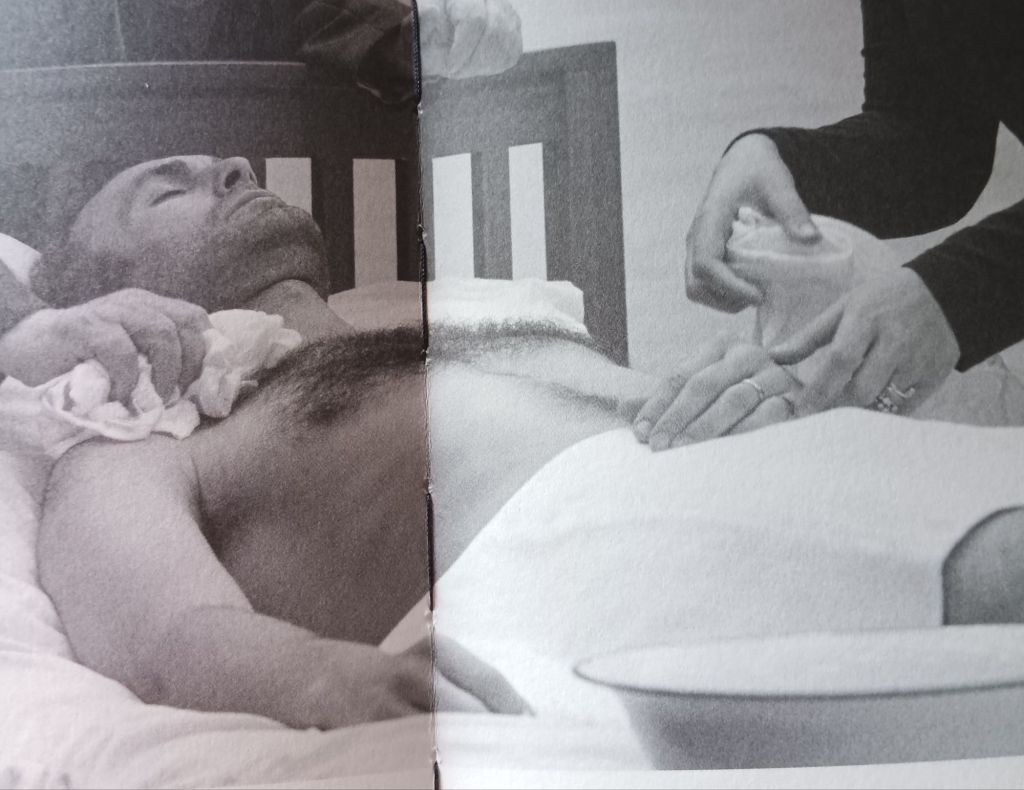

Likewise when Omar and Alice are joined in fuller conversation, she from Bolsano in Italy where the Iceman’s naked body rests in a museum, and he still in London, she asks him to be naked on the bed for that is alone how she can imagine him without the cover of things she cannot interpret. Does this mean too that the play requires a level of response in which the pornographic-erotic cusp is difficult to draw in seeing Khalid, who is a beautiful man, beautifully fit, naked.

In no way can we avoid and feelings ideas related of course, but John Berger addressed this issue more fully in some ‘Notes for Mnemonic’ written for Simon McBurney and reproduced in [Site]. Berger asks McBurney to throw out of his head ideas of the simple ‘innocence’ in nakedness: nakedness is, and always must be associated with desire. But his understanding of that is nuanced. We desire the naked he says in order to ‘cover’ its recklessness and lack of disguise, its ‘bleakness’ with our response to it. It is essentially a mnemonic of the ‘human condition’.

Seeing a naked body of any age or either sex, we remember our own, and the contact of our own from birth onwards with other bodies. Such contacts were tactile: they involved touching and being touched. They were also metaphoric for they were a demonstration of the similitude of all human bodies. … It is where empathy begins. It is how one can put oneself in somebody else’s place in the gully, for example, five thousand years ago. [3]

And perhaps that is it. The careful attendance on the joint body of Khalid / Omar / Ötzi the Iceman by others touching him both is an act of desire, care, love and curation, and these are never far apart truly understood if they are to be imagined appropriately. The opposite of such attendance is framing bodies by some form of regulated instrument: a freezer with a rectangular window for science to peer through or a frame of discourse that impersonalises, like all the contributors at the Bolsano Conference on the Iceman, even the feminist one, for it is the empathetic attitude to the body that matters leading as it does from that similitude to the differences that cultural imagination dresses similitude in, not just the dynamics of power, however important these too are.

Do seethisa if you can get a seat But avoid reading the Clapp-trap in The Observer about it.

Love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] Susannah Clapp (2024: 31) ‘Tricks of the mind’ in The Observer Culture Supplement, Sunday 7t July 2024, 31

[2] Simon McBurney (2024: 7) ‘Site’ in Tim Bell and Simon McBurney (curators) & Russell Warren-Fisher (book design) [2024: 7] Complicité: Mnemonic [A Site], Colophon, 7 – 15.

[3] John Berger (2024: 167f.) ‘Notes for Mnemonic’ in ibid: 167f.

One thought on “This blog is about eventually seeing ‘Mnemonic’ for myself in the Olivier Theatre at 7.30 p.m. 10th July 2024.”