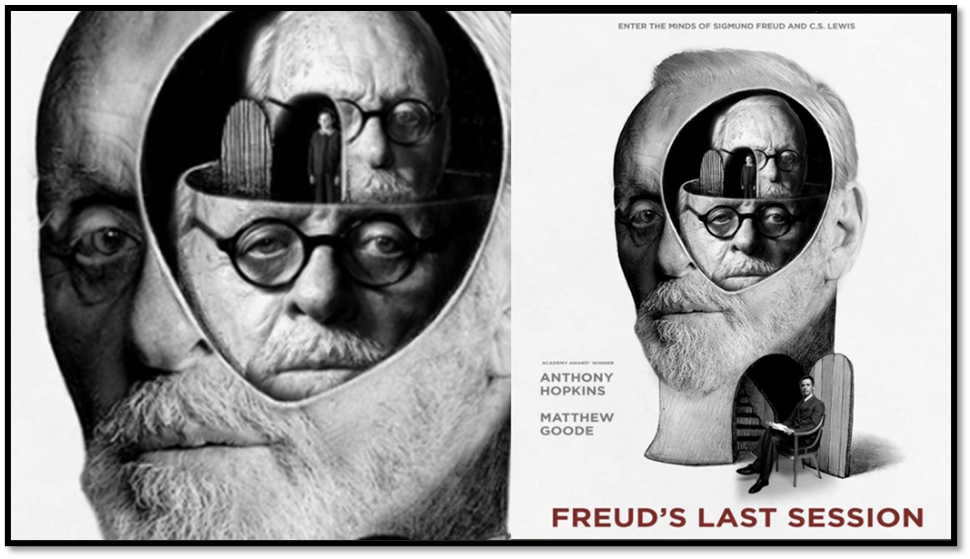

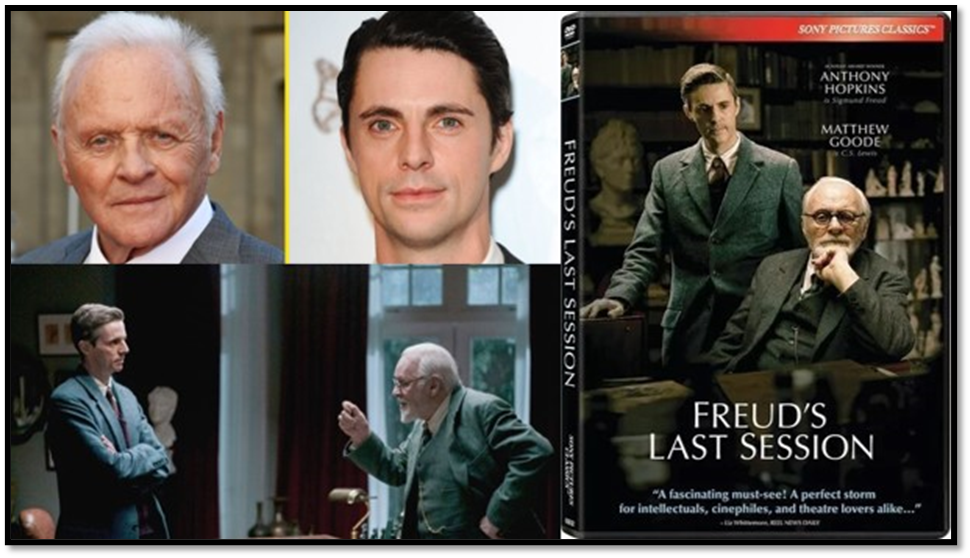

This blog is a queer take on Matthew Brown’s film Freud’s Last Session. In one of the fast shifting moments of the fragmented discussions between the two men (supposedly about the source of love and meaning in the face of human mortality), Anthony Hopkins as Freud asks C.S. Lewis, played by Matthew Goode: ‘Does homosexuality offend you?’ Rightly or wrongly, I sense that the film is haunted by queerness that subsists within any form of interactive ‘session’ between two people who interact in talk, therapy, or even conversation. Hence I think the film underwhelms critics, whether they say they like it or not.

There is a power in films where things are unsaid or alternatively hinted in an excess of signification in a statement whose importance seems to be missed bu most journalistic critics in Matthew Brown’s Freud’s Last Session. Any word may hint at such signification and take us deep into the interaction, as I hope to show later in the word ‘relationship’. Mark Kermode, noting that he had undergone his own analysis at the time of filming his, claims, in his Take on Freud’s Last Session with Simon Mayo, that for a film supposedly on analysis, says, ‘it does not go very deep’ nor leave mysteries open. He goes on to say that, because everything in it is said or enacted quite openly and overtly, and that there is no room for that which is hidden between people to emerge, discovered in the manner of psychoanalysis. There are, it seems, no factors left for analysis and it is instead an empty play with words, and because it was once literally a stage play with only two characters, it is ‘stagey’. Even the eventual probable overdose of morphine taken by Freud to end his life, a few days after the imagined scene, is treated in an underwhelmed fashion: ‘the only overdose’ in it’, Kermode says, ‘is an overdose of acting pills’. As he giggles like a man possessed by finding Anthony Hopkins’ acting more and more inauthentic as the film goes on. In illustration, he says further that though Hopkins performs his Freud with a bland middle-European accent, his accent ‘becomes Welsh when Freud becomes agitated’ and must be acted out.[1]

In truth, I think Hopkins acts Freud better than any actor ever has, since Freud himself. I have never heard an actor breathe in such a laboured way as Hopkins does to mime the effect of air obstruction by both Freud’s mouth and throat cancer and his metal prosthesis fitted to substitute for surgically removed mouth and throat parts. Moreover, the tonal qualities of his voice constantly act out conscious and unconscious inner dramas, in which anger, anxiety, sadness and solicitous loving care for human pain come and go in its rhythms. What Kermode also seems to miss, as do most critics of the film, is that its most consistent theme is a queer content that is hiding in plain sight. Indeed he thinks most of the characters added to the filmscript from the original stage script, who dramatise that, entirely superfluous to it. If he is right, as Freud says to Lewis, played of course by Matthew Goode, about the intuition of the existence of God, ‘one of us is a fool’.

However, I wonder, how attuned Kermode is to the varieties of contemporary psychoanalysis or how empathetic to that true perception of Freud’s about himself, used in the film: “Well, I’m human and I’m deeply damaged and no doubt I’m damaging to others”. This comes when Lewis accuses him of ‘being a walking contradiction’ as he claims that everything is sexual but shows that is so only unless it is inconvenient to not think so, as when you psychoanalyse your own daughter. Nevertheless Freud admits to the oral sexual pleasure of a cigar – the hidden point of his famous motif: ‘Sometimes a cigar is ONLY a cigar’.

It seems to me that this film is constantly shifting into the queer. In a Behind The Scenes documentary provided with the USA DVD I watched, Matthew Brown asserts that the film constantly asserts its proximity to dream and fantasy, with the contradictions dream and fantasy contain. There is, for instance, a constant shift in what used to be called the unities of time and place. Too much happens and in too many places to be possible in the one afternoon, the day World War II is called by Chamberlain in a piece of audio history. Preparations for raid in London seem overly anachronistic. There are changes in weather that are extreme, and hard to adjust to, that seem sometimes to be there to obscure Freud from us as he gazes through a window becoming increasingly opaque with the flow of rain on it.

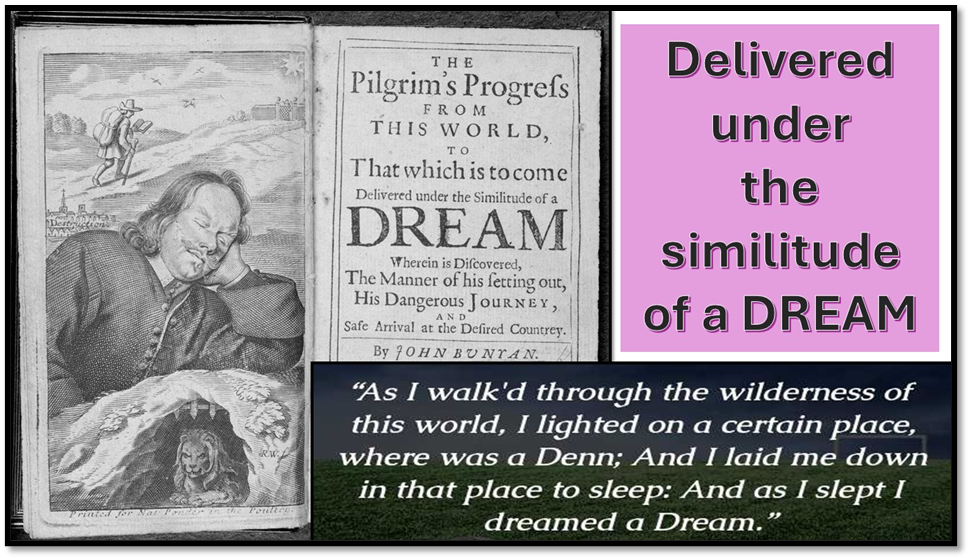

Stories from the past are often suggested by symbolism. Some of this is reflected in the epigram of the film from John Bunya where the wandering of Christian in The Pilgrim’s Progress is likened to a dream. The ‘den’ becomes the motif of that treasure trove of representations of Ancient Gods in his studio, still seeable at The Freud Museum.

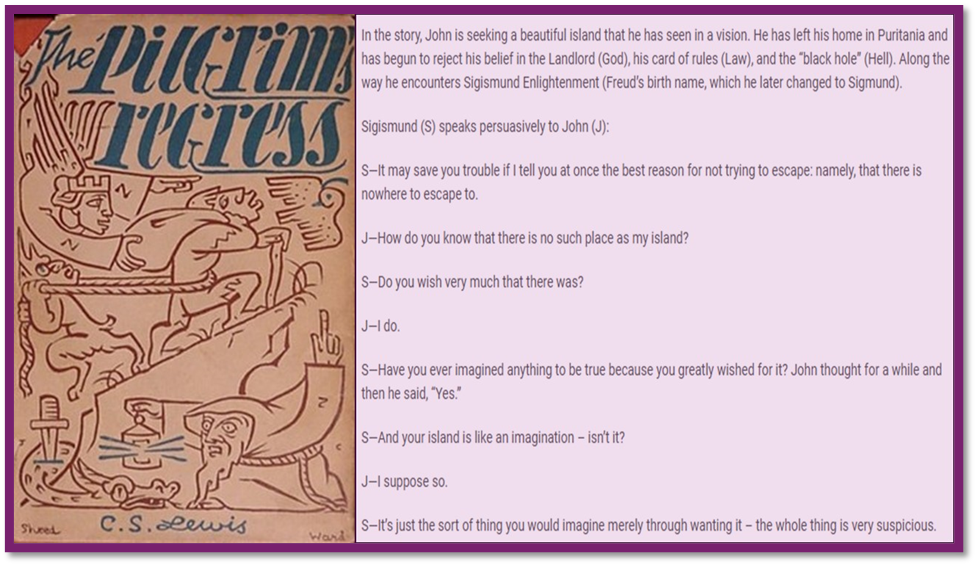

However, Lewis also wrote a parodic version of The Pilgrim’s Progress, entitled The Pilgrim’s Regress (with a bow to Freud’s therapeutic use of regression to childhood fantasy). It is a book both quoted in the film and shown in hard copy at the film’s denouement. In this book the temptations the beset the pilgrim in Bunyan, are for the character ‘John’ in Lewis those of modern materialist ideas. John meets Sigismund (Freud’s actual birth name) Enlightenment. This satirical portrait involves a parody of Freud’s belief that religion is a form of wish-fulfilment, the substance of a dream. Lewis wanted to show that this does not negate the reality of religion. We do not know if Lewis was the ‘Oxford don’ who met Freud near the end of his life by suicide but in the film, Freud’s gift to Lewis is to return that very book with his own dedication to the necessity of error:

The film’s woods and wildernesses that appear in dream and fantasy sequences of the film then have some relation to this allegoric story that sustains an apology for Christian religion against material demons posing as enlightenment. In Freud the basic wish fulfilment is often a compromise between the desire of the dreamer for something unconscious to it that poses as its most acceptable conscious substitute. Telling the story of his war trauma, for instance, Lewis falls into a bunker into the arms of a dead man, who isn’t Paddy who has just died and who may be a German soldier. Being buried in the arms of an anonymous man, represented as foe but embraced as a lover, is clearly rampant with possible hidden suggestion and the fearfulness of the dream bespeaks the regression of the Lewis character to childhood sexual fantasy.

Dreams too in the film often take place in corridors like those of Freud’s homes in both Vienna (19, Bergasse) or Maresfield Road in London and involve interactions with statues who are themselves interacting sexually. Freud speaks of, as a boy, having ‘a strong desire to walk in the woods’. There is a recurrent dream of walking in a wood or wilderness, like that behind the wardrobe in the Narnia stories (or the opening of Dante’s Inferno) haunted by a fawn, and reminiscent of the wilderness in Bunyan’s dream.

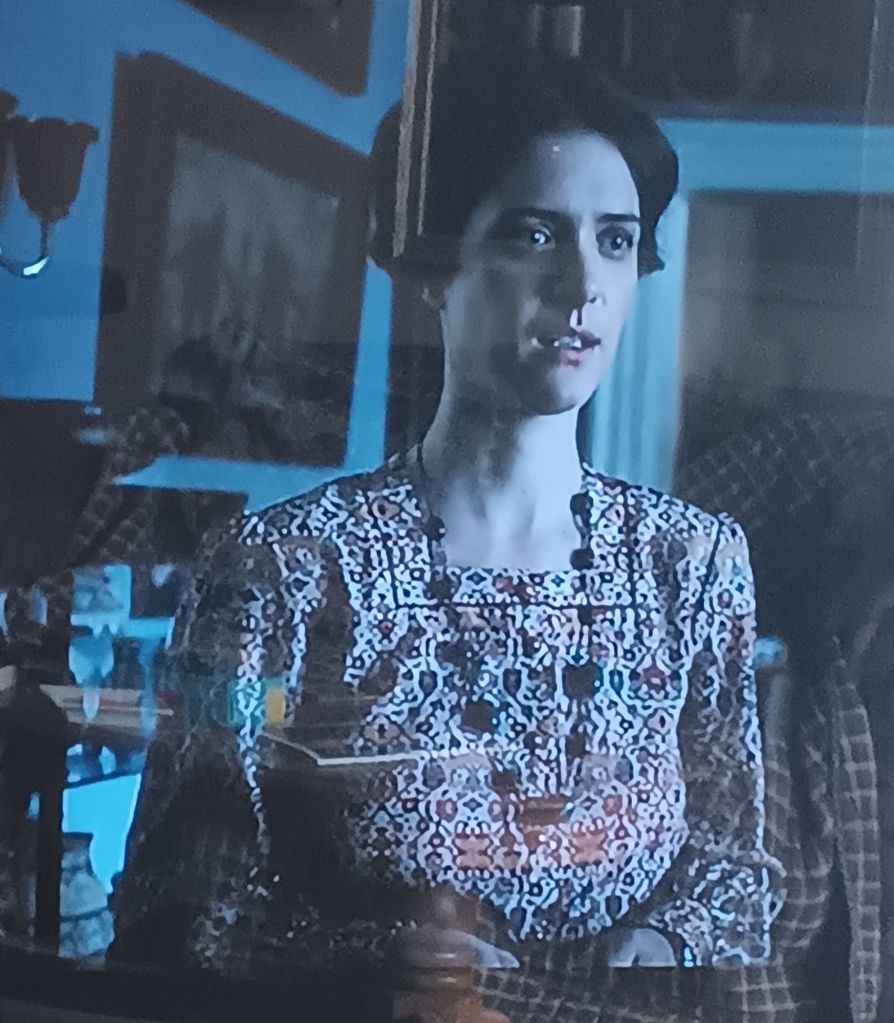

As I watched the film, and as I reflect on what I saw now, I become more and more conscious of queer content, neither necessarily homosexual or heterosexual just guided by unconventional public desire (for the period) and sometimes taking the form of art, into which Freud felt sexuality could be sublimated and hence defended against. In one heightened section for instance, after Lewis has probed who was the analyst delivering Anna Freud’s analysis, the admission that it was Freud himself launches a dream-like sequence reviving that analysis. The scene is distorted and unreal, which may be a dream of any of the main characters including Anna Freud (played by the amazing Liv Lisa Fries) to whom we cut sometimes during the Lewis-Freud conversation. Freud in it withdraws from Anna’s analysis saying: ‘You are not a boy or a girl, you are my daughter’. That sex/gender is conflated in order to be rescued by a family role is typical of dream action and the negation of interpretation, as Anna explores it in terms of her sexuality and role as a learning analyst. The scene is at its most painful, when Anna leans into her father and says ‘I need you …’ repeatedly.

I wonder how much of a film then some critics see. Stephen Farber for The Hollywood Reporter says, including some of what I have said above:

At one point Freud tells Lewis that he psychoanalyzed Anna himself, something that would today be considered an outrageous breach of professional ethics. The issue is raised and then dropped. We also learn of Anna’s lesbian relationship with a fellow analyst, Dorothy Burlingham (Jodi Balfour), which her father has trouble accepting. In one scene Freud reveals surprising tolerance toward male homosexuality but expresses his disapproval of lesbianism. This probably reflects sexist prejudices rampant at the time, but the subject is left unresolved.[2]

But why should such material be ‘resolved’? The entire point is that sexuality, of any kind, including incest, is deliberately covered up. After Freud asks Lewis if ‘homosexuality offends’ him, because he reacts badly to being asked if he lives with anyone (man or woman, Freud spells out), Lewis retorts by asking if Anna is seeing anyone, man or woman? Freud knows the answer but denies he knows it. Likewise, the real psychoanalyst and Freud’s first English biographer, Ernest Jones in the film (Jeremy Northam – once a heart-throb), points out to Freud that Anna can be rescued, by him, for ’normal’ sexual relations – quite characteristic of this less than Freudian English Freudian. As we see Anna Freud and the real Dorothy Burlingham flirt and make plans for the time after her father’s death we also learn in flashback that Freud was Burlingham’s analyst too and that Anna had been discussed in this therapy (the flashback conversation takes place on a staircase after a session between Freud and Dorothy):

ANNA: So then, he knows?

DOROTHY; He knows!

Of course Freud knew that you could know something and not know it at the same time, sometimes strategically. Wrong-footed by Matthew about whether Anna would see a ‘man’ or ‘woman’ as a partner, Freud falls into himself, eventually saying: ‘Lesbianism is different’. Yet there is clarity in sexual relationship only its lack of it and the obscure connections between people possible. This should bring us to Lewis himself.

Quizzed by Freud about his living arrangements as we’ve seen, Lewis, apparently confused, says that he once lived with his brother, Warren: ‘it’s complicated’, he says without further explanation but ending with: ‘My private life is precisely that’. In one of the flashbacks in the film Lewis however, recalls his friendship with Paddy Moore, played by George Andrew-Clarke (a nice enough lad and clearly a dish )who asks him to promise to care for his mother should he die.

After Paddy’s death in No-Man’s Land (at this an analyst’s ears prick up) Lewis tells Paddy’s mother, Janie, played by Orla Brady, that he himself was dangerously wounded himself in the incident that killed Paddy: “The shrapnel that killed him. A piece of it is I buried in my chest. Too near my heart to be removed”. The complex pattern of ‘family romance’ hinted in the excess of signification in that sentence, seems deliberately ignored by critics, whether they like the film or not. If Paddy is ‘too near my heart to be removed’ his role after death is taken by his mother, seen several times as Lewis’s companion and lover. Freud picking up on the transference of affections in the matter of a family romance asks Jack about the ‘relationship’.

Lewis in classic Freudian repressive denial says that his friendship with Janey Moore, and presumably that with her dead son Paddy Moore before that, is ‘not a relationship’, for in English a ‘relationship’ signifies especial connection that may be sexual and / or romantic. Freud’s statement in response in the film is that ‘any bond between two people is a relationship’. None of this is in the original play, or the book about a debate about God that prompted the film. The point is that all relationships are potentially queer bonds directly or indirectly. Men who lose male attachments, Hopkin’s Freud says, often then choose older women in substitute. It is all well explored but, of course, not ever on the surface as Farber wants it. This directly contradicts Kermode, who says that it IS ALL ON THE SURFACE, as I said before.

Of course, the film is also about that wishful relationship to an authoritative desirable father that is God. In an interview with Nell Minow in the online zine RogerEbert.com Matthew Brown discusses the film entirely in these terms, an intellectual discussion about whether and how two great intellectual minds could have ‘tolerance’ for each other. The nearest Brown gets to showing the film’s sexual underbelly is when answering why Anna appears so largely in it, resolved into its issues or not (and definitely not for Kermode) – though critically not for Kermode, Here is the question and answer:

The real Anna Freud when young

The film also devotes a lot of attention to Freud’s daughter, Anna. Why was that important?

That is something that evolved definitely from the play into the screenplay. You can’t really understand Freud unless you understand his relationship with his daughters. I think that losing Sophie Freud to him crushed him. She was very, very charismatic, the beautiful apple of his eye. Anna was probably a much more complex situation and relationship for Freud. She went on to do some pretty amazing work. But, she had a big shadow over her. That was a challenging relationship, so I felt like you had two therapy sessions going on.[3]

In the film Anna is quizzed by her teaching colleagues about the time off she has to care for her father to which she exclaims: ‘He is my FATHER!’. Her colleague says: “Yes! And what else?’. The film intends that question to have no easy answer for all relationships are made up of transference and counter-transference between past relationships and dreams. And in part the key sexual relationship in the film is that between Freud and Lewis (often played out like that with Jung in their letters), operating under screens of sublimation and other kinds of repression. Lewis is quick to realise that one strategy to keep Anna close is to insist that she, and only she (and especially not medical doctors) can handle his personal care and especially care of his throat and mouth prosthesis following the removal of part of his growing cancer.

No-one wanted, one has to say, much to get near him because of the smell of decay as well as the protestations of pain involved with proximity to his mouth. ‘Anna calls it my monster’, says Freud as innocently as he can of his prosthesis. Anna is subjected to handling parts of her father both of them fear and loathe. However, as Freud’s pain worsens and a promised morphine delivery fails to come, Freud feels that he can ask Lewis instead to remove his prosthesis manually by putting his fingers in his mouth and to looking within: ‘Look in there. Hell has already arrived’. The handling of this is as fine a representation of repressed proximity as I have ever seen.

Brown says to Minow that his mantra for the meaning of his last film was: ‘the cost that comes waiting out of fear to connect for two people’. Mantras, he says, keep a director focused and clear about what they want a film of theirs to say. He does not give us the ‘mantra’ for this film, but what, if it is the same and that connection is a need that is the equivalent of the search for God and a father figure who reconciles. That search cannot be told simply. Hence Farber as a critic is at his most inappropriate when he says:

But the heart of the story is constantly undermined by a surfeit of asides about Lewis’ experiences in the First World War, Freud’s highly charged relationship with his daughter Anna, and several other subplots.

The main culprit here may be the current fashion for time-fractured, nonlinear narratives. It is rare these days to see a movie that unfolds in strict chronological order.

There will always be searches for simple answers and even simple stories for complex realities and the weft and warp of real stories in real time. The least appropriate place to look for these would be a film about Freud, or even that complicated group of English fantasists, The Inklings (the major figures being Tolkien and Lewis).

Do see this film. It is worth it even if you don’t buy anything I say to see Matthew Goode talking the look-a-like of Freud’s chow dog, Jofi for a walk (there is license here – Jofi had died by then, his last dog was Lun). Leaving a park as the rain begins, the two see a poster advertising a local lecture by Freud. Jofi wees against the pole holding the poster, lifting his leg more than you could think possible.

With love

Steve xxxxxxxxx

[1] Mark Kermode, as in my notes, based on Mark Kermode & Simon Mayo (2024) ‘Review’ in Take on … Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WtkLeosFU1o

[2] STEPHEN FARBER (2023) “‘Freud’s Last Session’ Review: Ace Turns by Anthony Hopkins and Matthew Goode Are Undercut by Subplot Overload” in The Hollywood Reporter (online) OCTOBER 28, 2023 7:53PM. Available at: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-reviews/freuds-last-session-review-anthony-hopkins-matthew-goode-matthew-brown-1235630951/

[3] Nell Minow (2023) Interview: ‘It’s Down to Two People Having Respect for One Another: Matthew Brown on Freud’s Last Session’ in RogerEgbert.com (online review) December 19, 2023, available at: https://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/its-down-to-two-people-having-respect-for-one-another-matthew-brown-on-freuds-last-session