In a profound new novel of queer romantic and sexual love between older men, a Serbian landscape-gardener, Ivan, talks, in a plush flat rented for the night, with a young sex-worker called Troy, also rented for the night, about the latter’s father. Ivan imagines Troy’s father must be older than him but only just, but is otherwise, he also thinks, similar: ‘A child of migrants, in the In-between, like me. He doesn’t speak these thoughts. He doesn’t think Troy will understand and he isn’t sure he can explain them’.[1] This blog attempts to articulate what it is to be and feel ‘in-between’ in The In-Between (2024, 2023 in Australia) by Christos Tsiolkas.[2]

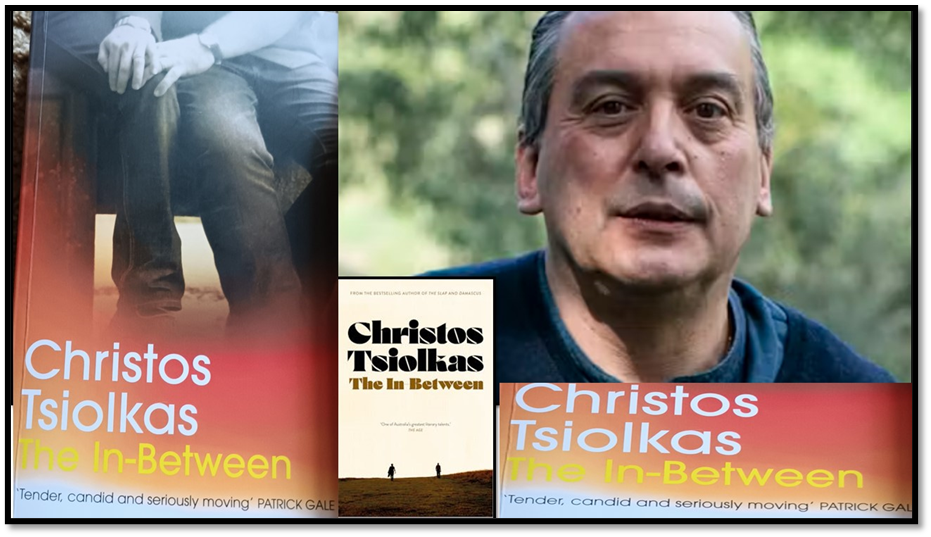

I last blogged on Christos Tsiolkas about a very different novel, Damascus, set in the period of the earliest Christian communities. You can read the blog at this link. However, it is a very different novel – though equally committed to find queer histories that have rested in-between other major and minor clashes of culture. I mention minor ones for The Slap is predicated, as you might guess, on one such minor socio-cultural clashes involving cultures, slapping. But, although it will not help you with this novel, I find almost every novel including Damascus of this wonderful novelist (with a major confession that I have not read, or possess yet, a copy of his last before The In-Between, named 71/2). In The In-Between, both the main protagonists, Perry and Ivan are middle-aged men with histories, sexual and psycho-cultural.

The translator of text, Perry’s, past long relationship with a heterosexually-married man with young children, called Gerard, involved him in the latter’s passion for languages and for the classical culture of Ancient Greece, Hellenistic and early-Christian Greece (a culture more properly his already because he is Greek; his full name: Περικλῆς, Périclès). His lover in the novel’s evolving snatches an evolving present is Ivan, a second-generation Serbian migrant small-project landscape gardener, had been heterosexually married himself, fathered a daughter, Kat, but had also been in a long relationship that had split this marriage, with a former employee of his, Joe, who having admired his boss’s cock in the toilets of a public house, became his business and life-partner in co-ownership of a shared house. Joe, in turn, cheated on Ivan and left him together with a settlement of half their home after Ivan beat him up in the only real instance of domestic violence seen in the novel, other than the ‘DV’ acronym talked about at a middle-class dinner party of earnest middle-class people working in the domain.

You will find those histories complicated enough, were it not that the contrasting second-generation migrant cultures of both men divide and unite them in culture, for Ivan’s Serbia still shared an ancient background in militant Roman and Byzantine Imperial conquest and versions of the same Greek-speaking Orthodox Church, powerful even on non-Christians of the culture. Of course, it is the same Church as that of Perry, and Anna Zangalis, merely a gardening client of Ivan’s, with a fondness for serving workmen and her sons with Greek delicacies and sweets, that Ivan understands enough to feel like both, enough to intuit his welcome at Anna’s funeral.

The slippage in-between cultures that are also distinct is common to Tsiolkas’ works, whether these be of migrant national communities or communities of identity, where identity is also slippery, liminal and fused in its in-betweens, whether these be lesbian, gay, bi- or heterosexual, or class communities with different understandings of what makes for a dinner engagement. In an over-educated middle-class dinner party Ivan feels like a cultural ‘outsider’.[3] He is so in many ways: he has never travelled for work or holiday in another country and works manually. The dinner-party simmers with some of the real life tensions and gut-clenching fear of rupture in some encounters between lesbians and gay men.

Beejay Silcox reviewing the Australian publication of book for The Guardian thinks the dinner party scene ‘is so monstrously awkward and gloriously well-observed it could be a one-act play – a study in the quiet tyranny of consensus’.[4] To outsiders enforced consensus is a weapon used against them in countless micro-aggressions. Even more nervously charged is the discussion in a taxi between three men about whether sometimes some women are partially responsible for rape.[5] Neil Bartlett, himself a fine queer novelist and playwright like Tsiolkas, puts all this rather well, and simply, in his review of the UK publication, also for The Guardian, demonstrating the slippage from what is in-between all of the the novel’s contrasting social identity groups, in the supposed gaps between social barriers (of first or preferred language sometimes) to their necessitated interconnections:

Against this ever-shifting background, the title of the book acquires subtly interconnected meanings. As the gay sons of immigrants, Perry and Ivan live in between cultures; as gay men who have been entangled with heterosexuals, they live in between sexualities; as present-day, middle-aged gay Australians, they have to navigate a growing desire to fully commit to each other as a couple in a country that still lies halfway between its homophobic past and a future of potential freedom.[6]

This is good because it plays with the idea that the past, present and future of the characters, though they claim to be distinct entities for each of them, with spaces in-between, turn out to be full of interconnections, and sometimes occupying intrusions or other cultural interlay that unites both, as the English language often does as a lingua franca between people happy in many languages – notably in the last section. Gerard’s daughter, Léna, who is a polyglot archaeologist, competent in Greek, French, English and some Arabic (people who often translate between languages are go-in-betweens anyway). I think the issues in Damascus arise again in this thematic strand of both novels.

Perry in transit across his Australian city listens to podcasts. Once, before he met Ivan (for by this time the chapters have skipped much time ‘in-between’ in the establishment of their relationship) Perry had listened to ‘political broadcasts’, ‘analysis of current affairs’, or ‘features on books and film’ (as well as the odd ‘queer podcast’). Ivan had persuaded him on their first holiday together to become interested, an interest he later takes autonomously into the level of being ‘engrossed’, in ‘the complicated history of the Roman Republic’ told lazily in a ‘Midwestern drawl’ from the USA on ‘history’ podcasts. As he listens, the story of the Roman Republic, even its transformation through conquered Hellenistic Greece, to the Byzantine Christian , their Imperial successor, becomes interconnected as in-betweens must with the way his relationship to Ivan mutates.

After the division of the Empires

Ivan’s ‘wariness’ of current political discourse and its evasions forces him to take ‘respite in history’, a wariness of some use in the dinner-party to come.

There was respite in history. The belligerence and intolerance of the contemporary age was of no consequence to the past. And there was no shouting. The history of Rime had led him to the history of Byzantium. He was grateful to Ivan: he was now far less agitated on the commute to and from work.[7]

This is a considerably more nuanced reflection that it sounds for ‘history’ is only removed from the drama of aggression (micro and macro) because it is not ‘current’, its combatants dead and its outcomes accepted as given rather than to be fought or shouted for. There was as all the people in the novel know much fighting and much shouting in the ‘in-between’ through which the Roman Republic became the Byzantine Empire, centred on Constantinople but Roman in principle and law, Greek in spirit and eventually on the cusp of the whole Eastern world in rule, a rule in which other Empires, Slavic (like that of Ivan), Greek, like that of Perry and Anna Zangalis, get birthed and spread by diasporic migrations. The ‘shouting’ and minor violence in many parts of the novel recall these migrations and their contemporary analogues, the forces of power through hegemony and enforcement of linguistic and cultural imperiums, even that of the cool left-wing and green principles of former university colleges over working-class Serbs, quietly stoic in their formulations. If history is respite, it is only so when the story seems established and its transitions robbed of the currency of affairs.

The past especially haunts the latter novel stressing the length of ‘in-betweens’ that stand between major events that must be noticed. When Ivan chooses a rent-boy, he gets Troy, a third-generation Indian migrant thoroughly Australianised. Troy even tells him a plausible story of how he got the name from his father’s snobbish dislike for the Australians: ‘Uncultured thugs’. This father is a man to whom the name of Alexander the Great and his violent incursions into India mattered, as did the Indianisation noted in the late Alexander, though all that has to be presumed. The talk about this starts when Troy corrects Ivan when he says that the name of his partner, Perry, as already noted above) is Pericles (the novel even further refines this for some (Léna for instance) by accenting it as transliterated Greek ought to be, Périclès. Ivan telling the story to Troy believes it is the name of a Greek god. Troy corrects him to insist, rightly, that Pericles was ‘a leader of ancient Athens’.

Ivan chuckles. “you know your history.”

“I like history. Always have. When I was a kid, my dad used to read to me from a book about ancient Greece. He said Greece was one of the few places in the world that could compare to India when it came to history and culture’.

Troy’s mother had intended his name had to be Ganesh, he tells Ivan, but this was stopped by his father’s snobbishness, to Troy’s reported present relief, in not being known as ‘Elephant Boy’ or worse ‘Gav’. When Troy attributes being given this name by his Hellenophile father, Ivan ‘asks casually, “So Troy’s your real name?”. The implication is clear that sex workers use fictive names with their clients and this is certainly how Troy reacts, as if insulted micro-aggressively, ‘rolling away from Ivan to the other edge of the bed’ and asserting his name again, ‘something in the tone conveying distance even more acutely than the physical separation’. [8]

This example could be the most perfect example of how stereotypes for cultural preference are used to dramatise other cultural dissonances like those between paying customers and sex-workers. Yet, strangely enough, the evening at an end we learn that Troy is not the sex worker’s name. As he contemplates which of three paying customers he will visit next, his taxi-driver wonders where he wants to stop next and asks. ‘We making a stop?’ The next paragraph is wonderful for we learn that the sex worker is, at this moment, not Troy, as he starts off the section of the novel, but Aaron: ‘Aaron nods and sinks back into his seat. He is thinking of the sex he is going to have, …, of the beauty of the night, and how full of adventure it feels’.[9]

No authorial intervention marks this name change, including the move from a name derived from Greek to one associated with the Jewish Bible or clarifies how his parents really named him and why. My own feeling is that almost unnoticeable moment is registering the lack of distinct boundaries with which anyone is capable of living, and the shifts we can make possible in this liminal space in-between categories we like to think distinct. Beejay Silcox uses the word ‘liminal’ too of the novel but with some embarrassment because one of their editors often delete it from reviews as a ‘gauzy wank-word’ (whatever that is) to describe the book as a whole as ‘a tale of halfway places and emotional purgatories: of middle age, middle politics and the middle classes’. They could have added middle or mixed nationalities or cultures and ‘middle’ or mixed languages of cultural reference.

There is no doubt that, in some ways, finds Ivan’s working-class naturalised Australian self is hard for the over-educated man refined by the French tastes and Greek myth-making of his earlier lover, Gerard finds Ivan’s ‘elemental solidity’ hard to take ([10]) socially as well as rather extremely sexy in his eyes and nose, for his ‘strong perfume, carnal and animal, the blatant odorous pungency of a man’ excites him without taking away his assessment of all Ivan’s ‘blemishes, all asymmetries, his too large earlobes and uneven, discoloured teeth, the sagging jowls’, that will out in company of his own class, even with the sophisticated multicultural Léna, Gerard’s daughter, when they all meet in Athens. Jessica Gildersleeve writing for the online magazine The Conversation calls such moments where cultural assumptions about national or continental types produce moments of ‘cultural cringe’, where, for instance we might type all Australians as many characters’ do, including the fictive Troy’s possibly fictive father as ignorant, racist and conservative. She has a lot to add about this and I think it is worth quoting her at more length as she talks about the tendency in these middling classes to write off Australian character, especially in men, and Australia as:

“a racist shithole”. These are characters “in-between” class, “middle-class Australians” with a “tendency […] to endlessly deride their own country”, demonstrating a “habit” shared by “the bourgeoisie the world over”, as Perry observes. “Cosmopolitan Europeans are just as annoying in their shallow, condescending generalisations,” he continues.

Such generalisations pepper the narrative, and are even shared by Perry himself, who thinks, for instance, “Touts les australiens sont comme des enfants”. (All Australians are like children.) Meanwhile, a Greek taxi driver criticises Australians’ insularity and their reluctance to learn even a few words of his language. A guest in a restaurant (misidentifying the men’s nationality) mocks Ivan for making a loud expression of approval: “It’s morning and the Englishman is already drunk.”

These kinds of derision represent criticism without an ethic of care, or tolerance for the other. Instead, Tsiolkas celebrates – as he does in all of his work – those who create, tend, or share. Especially when this is constituted by manual labour: the work of the hands.

Stu, Ivan’s workmate, a gardener and landscaper, possesses an “odour” that “is harsh, defiant, that compound of sweat and tobacco and earth, the masculine scents simultaneously sour and stirring”. [11]

When Perry joins his class compatriots in an negative attitudes to Australians, he does so in the ‘refined’ French of Gerard, and later of Léna. I think Gildersleeve is also correct to see the liking, as sexual as well as that between people of integrity in recognition of their mutual value, of manual labourers and their honest smells, although it would be wrong to see that, as she seems to do, as simply celebration without nuanced awareness of the tensions such choices make for the ‘cultured’. The novel stays more in the ‘in-between’ finally than does Gildersleeve’s assessment of it. Adam Rivett, an Australian male, writing for The Sydney Morning Herald finds, like me, that same in-betweenness characteristic of the novel, although he calls it ‘indeterminacy’, and indeterminacy is often uncomfortable. Rivett presents that ‘in-between’ indeterminacy as a lesson everyone must learn, including the to and fro of sexual desire between disgust at over-insistent carnal smells and being turned-on by them, by inbuilt social embarrassment that belies ones principled spiration to demonstrating the importance of human equality:

The book’s title is purest philosophy – everything is somewhere between left and right, dogmatism and permissiveness, care and abandonment.

This desire to build an entire work out of indeterminacy permeates the book’s structure. Instead of the short, choppy scenes of much modern fiction, novels written either with future adaptation in mind, or perhaps with Netflix lazily streaming in the background, most of The In-Between consists of long, deliberate, and patient scenes in which power and knowledge carefully move and shift between people.

In these theatrical blocks of prose – a date, a hookup, a day at work – Tsiolkas affords himself the time to register uncertainty resolving into joy, or, alternately, certainty itself abandoning the once comfortable and secure.[12]

And being in-between is where the reader must stand too. Both Rivett and Gildersleeve rightly pick out that the novel is essentially about how and why ‘care’ is necessary in a relationship and how it both happens when it does and when it does not. Every critic picks out the final scene as exemplary of Tsiolkas’ best writing. It is described superbly by Neil Bartlett who compare it to the ending of Sebald’s The Emigrants, without spelling out the similar theme based in migrant experience. That may or may not be useful. However what is certainly useful is his noticing of the classical reference in the scene to Ovid. The point is that the scene works whether you get that reference or not – it is still a game played between high and low culture to those who make such distinctions, for whom the knowledge of classical literature is a stamp of their elitism. For the heterosexual Greek couple described, for whom history is continuous from Attic Greek settler trading Empire to the fall of ‘the city’ as Greeks term, Constantinople, the comparison may seem apt, as indeed it would be for the autodidact, of Slavic Byzantine origine, Ivan. But here is Bartlett:

In the sixth and final move of his authorial viewpoint away from his leading characters, he tracks an elderly married couple down a backstreet in a small town outside Athens, where the novel has moved for its radiant final sequence. They bicker and fuss, then disappear.

Although this old couple have different names, their well-worn devotion clearly evokes the legendary figures of Philemon and Baucis, the humble pair whose love is so strong that in the eighth book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses they are granted a wish to be eternally united. In Ovid, the lovers become a pair of conjoined trees. Tsiolkas evokes the reality of lifelong devotion with a cinematic fade to black; as darkness falls on this couple, it becomes impossible to be sure “where one ends and the other begins”.[13]

Bartlett writes this beautifully but he makes too much distinction for my taste between this ‘best’ of Tsiolkas’ writing and those parts of the novel that offer ‘quite a lot of frank and medium-filthy sex’, for exploring in the in-between of those modes matters for the novel. Bartlett seems to enjoy that too, but sees the ‘pornographic’ as lesser. However, the whole point of the frank sex is to remind us that sex and romance are not opposites and that ‘in-between’ them is the ground on which we form caring relationships too, even with Troy, however false his ‘name’ and cultural pretension. Beejay Silcox goes overboard in relegating the sex writing to a dark cupboard where one keeps pornography:

But then there is the sex: ferocious and sensory and relentless. Underneath all the bodily noise – the fug, fetor and pong – these scenes often read like anatomical Ikea (insert part X into slot Y). It feels performative – almost weaponised – like a game of erotic chicken: blink and you’re a prude. I’m tired of that pernicious little trap; I’m not scandalised, I’m weary.[14]

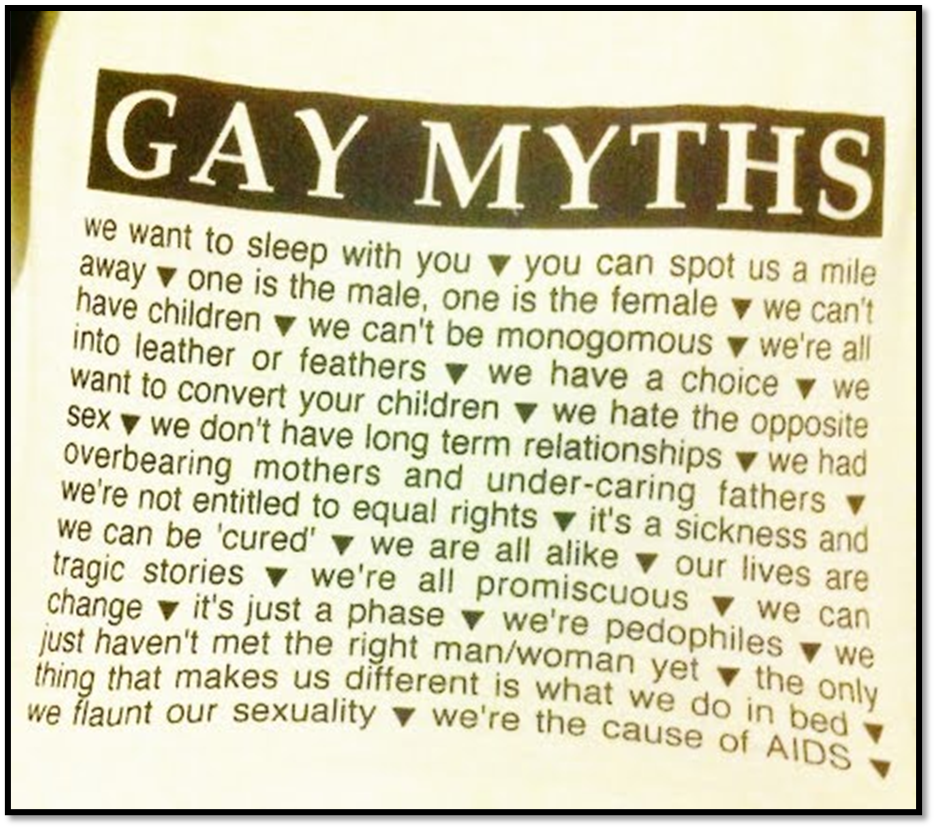

Silcox’s world weariness at having sex thrust under their nose by writers is not really forgivable. Queer writers in particular need to keep such writing both alive and specific, negotiating between the sense of taste and tastefulness, obscenity and beauty. The most effective tool in the suppression of queer sexualities, even a-sexualities, has been prurience about what gay, lesbian and bisexual people do and the claim to a right to find it ever so slightly disgusting, because of its nearness to the visceral and its reference sometimes to the excremental, as if heterosexual too did not bridge that gap too. The most beautiful moment relating to this this is where the old lady, Anna Zangalis rejoices that the young woman working for Ivan in her garden is happily lesbia.

Moreover, there is health in alerting queer people even to suppressed responses in their sex lives – ones better in the open than allowing them to determine myths, such as the potent ones about the size of the male sexual organ, or the indeterminacy or not of the clitoris, both of which are explored in The In Between. I think it healthy to have a passage like that below, without rushing to the Literary Review’s Bad Sex Award lists (now suspended) that were intended ‘to draw attention to the crude, tasteless, often perfunctory use of redundant passages of sexual description in the modern novel, and to discourage it’. But why discourage such writing because it opens up and out what occurs in the in-between sexual interactions, and shows the absurdities of myths prevalent there, with humour and grace:

Perry shuddered at his touch and there was a momentary intrusion of that silly juvenile fear: Would Ivan think his penis too small? But there was no easing of Ivan’s fervour: in his kissing, in his thrilling stroking of Perry’s cock. Perry was relieved, furiously eager.[15]

As Silcox shudders too, but with ‘weariness’ be it noted (insistently not distaste nor prudery), do we not get a hint that one of the reasons Silcox would censor this was because they want an end to all and every element of sexual education, into attitudes and prejudices about the body for instance, that lies in-between knowledge of the body and its desires. The use of a metaphor of sexual interaction as ‘dance’ is yet another breaking down of categories between culturally valorised and culturally taboo knowledge.[16] It is beautifully done. If it were not it would not cause the tensions Silcox believes they could do without. It is the mutuality of the ‘dance’ after all that distinguishes consensual sex from rape (also discussed in the novel).

Indeed we are too often so prurient about bodies that to care about them, and for them as Anna Zangalis does, is impossible. My favourite passage about ‘care’ (bless my social care soul) is about the care of the dying body, which is an analogous subject, too often disrupted by prurience from truly being care, It is in that very short piece about Rudi, who appears in the novel for only these two pages, describing her care for an ‘elderly Lebanese woman’, describing the ‘few moments when Rudi and the dying woman were intimate’. You either respect that word ‘intimate’ or you do not. You need to strain though to ensure you know why it is used of wiping from the lady the results of her involuntary self-soiling. How often in care work have I seen expressed disgust render ‘care’ given that involves faeces and urine turned into an interaction for the dying or ill that is, to say it bluntly, appalling and unethical. Nevertheless, we must understand those in-between places before we subject them to training as I did as a social work teacher.

The novel takes its duty to reflect and widen the discussions in the queer community seriously: hence its concern with contested notions of masculinity, relationships between lesbian and bisexual communities (though trans issues rarely appear on their own here), but most notably discussion of polysexual and monogamous relationships and the role of secrecy in ‘couple’ relationships. The discussion is comprehensive, ongoing and unconcluded as I will mention later; in fact, it is endlessly open as it is in the real world.

The important thing to draw out of this however is that this novel refuses to censor words that cause disgust or pain and indeed reproduces them whether as directed between different nationalities or cultures, between people of different sexual preferences, between sex/gender or class categories and their nuanced multiple intersections. It is vital for this novel, for instance, to examine the language available to describe queer people in different languages and cultures. Gerard dies torn up his disgust at the words available to describe his love of men. The word ‘faggot’ may seem insulting but how much worse to him, his daughter learns from his extant letters to use the French term pédé, the nearest word his linguist daughter can find being ‘pederast’ (indicating a love of sex with boys without the capacity for informed consent).[17] Perry discovers that Ivan hates the word ‘pooftah’ (one of its spellings in the novel) which causes ‘loathing that flashed in Ivan’s eyes’.[18] Words used about queer romance too have this awful way of falling ‘in-between’ cultures of translation and tolerance of others. When Gerard end his relationship with Pericles, he calls it ‘incovenant’:

He hadn’t immediately grasped the meaning of the word, had to look it up in English. Unseemly. By which he meant dirty.’

When Perry, having reflected on this determines he must face himself in a mirror where he repeats negative appellations given to his sexuality in different language cultures (French, Greek and English): ‘Pédé, pousti, poofter’ (in another spelling of the English word of higher-class pronunciation than Ivan’s).[19]

The book takes these points about words and attitude formation very seriously. Sometimes the book, full of linguists, translators, multicultural scholars and persons from regions with multiple languages in use – not least Australia) replicates the misunderstandings that fall between uses of the ‘same’ word. Ivan uses Serbian endearments to his daughter and is ‘glad to see her smile at the familiar endearment’.[20] I, like Perry with the French word above, had to look lutka up, and in Russian origin it means ‘indecent’ and is used of a ‘slut or ‘whore’. Yet in this father’s use it plays games with familiarity of contrary personal or familial meanings. To do all this without explanation shows how far in-between assumptions in language and cultures Tsiolkas wants us to dive. When Arthur Zangalis, for whom Ivan and his team are gardening, shouts at his wonderful mother Anna, in part causing her death, the ‘argument is raging in Greek’ and ‘only the expletives are in English’.[21] A whole line of the word ‘Fuck!’ is given as example. Shortly afterwards Ivan’s ex-wife telephones him and again language is an issue:

The abuse is vile. At first it’s almost funny, the demented logic and the incoherent fury: the words cazzo and faggot, intermingled with the accusations of him being a sexist and a misogynist and a toxic male’.[22]

Cazzo is Italian slang for ‘dickhead’ or something like that – definitively sexualised abuse nevertheless. But there is an element of misogynistic sexism in Ivan’s response and the fact that communication between people of different se/gender categories remains in-between traditional models of those categories persists in the novel too. People use slippage in-between languages sometimes as tool that can be indicative of attitudes to each other. Ivan wins a point for himself at the dinner-party scene with Cora and Yasmine because he can converse, in basic table manners form, Lebanese Arabic.[23]

Léna is so polyglot she uses multiple’ languages’, even playing, in the next quotation, between accented transliterated Greek (for Perry’s name) and non-transliterated Greek mixed with French: À dix heures? À café Ολγα Ψνρή. À bientot, Périclès’.[24] Of course in giving the café name in Greek letters (Olgs Psni) she bows to Perry’s second language, the Greek of his parents. When distracted she speaks to her lover, Vera, in Greek but ‘uses the French word distrait’.[25] She has to drop the Greek for Ivan on Perry’s request because he tells her Ivan knows none.[26] However Ivan himself converses in Greek, if shyly, with an Athenia taxi driver, just before the drivers shouts ‘Faggots’ at some boys who get in his way on the road. Yet Perry grasps the bull by horns when asked by the taxi-driver his relationship to Ivan and here untransliterated Greek plays a big role:

The simplicity of the Greek phrase – Είμαστε ζενγάρι – sounds old-fashioned, yet it is also perfect, direct and concise, allowing for no misinterpretations. We’re a couple.[27]

The Greek (Imaste zengari) of course suggest the bonding rather than the shy term ‘couple’ and defines the closest of relationships. The issue here that Perry confronts a loose homophobia with something that suggests the understanding and empathy and co-operation of the taxi-driver can be won. And, of course, it is.

And to return to the quotation in my title at last, the issue that is raised by the conflux of national, linguistic regional, class and gendered cultures is precisely that of crossing boundaries. Yet again Tsiolkas’ novel is about the prequels and sequels of migration, and what goes on between migrational flows (in time, space and in forming national identities like that of Australia). Ivan imagines the father in the possibly fictious Troy’s possibly fictitious story as ‘A child of migrants, in the In-between, like me. He doesn’t speak these thoughts. He doesn’t think Troy will understand and he isn’t sure he can explain them’.[28]

This father-figure is like Ivan perhaps, somewhere ‘in-between’ nations, ages and value systems, or so Ivan thinks, but he is also in-between worlds too for these ideas cannot properly be articulated in any of the languages the migrant is ‘in-between’ in their transit or transition. I noticed the term ‘in-between’ in the novel again, but here it is about translation of the untranslatable. Vera, Léna’s lover, says of the taking of responsible of Perry’s grief for her dead father, Gerard, as taking on ‘an enormous responsibility’. From here Léna drifts ino a world where no terminology is fixed, in terms of her father’s status as a sexual and human being, and of a man between worlds: he was Vera explains ‘a man who lived and loved in conflict, between two worlds’. Léna seems released by this into a state of consciousness that is itself ‘in-between worlds’, a migrant of time-travel:

Today she feels that she is on the border of time and floating above the world. As if she is in the in-between. As if she needs an anchor.[29]

The metaphor of the anchor and the vagueness of the spatial-temporal mysticism don’t work clearly together as clear communication but they are of the essence of the situation where the liminal is never grasped. It even coheres around language. Hearing Vera speak of ‘responsibility’ as I have already quoted:

For a moment, Léna is disconcerted, unsure if she has understood the word. Then translating it – ah yes, she means responsabilité – she is struck by how, as often with Greek, the word implies an active purpose rather than a mere emotion or condition Εγνδύη. She is undertaking a charge, a mission. An obligation.

Try yourself to seek an equivalent of Εγνδύη and you will find it difficult, although all the meanings Léna thinks of are appropriate and more. And even responsabilité In French may vary in its associations in ways the term ‘responsibility’ does not or may not. For being in-between is to be in translation as well as transit and transition. Migrants cannot be sure any experience of past, present and future will be the same for linguistic usage itself changes.

And somewhere elsewhere (some place in between certainties about self, nation, culture, sexuality and sex/gender) is where this novel sits: unsure where it is going but going there anyway for it has no choice like most migrants and migrations in history. And that is true of sexualities too and the words which name it – even those once seen as a slur.

I think this a most important queer novel. Do read it.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

.

[2] Christos Tsiolkas (2024: 242) The In-Between London, Atlantic Books Ltd.

[3] Ibid: 61

[4] Beejay Silcox (2023) ‘The In-Between by Christos Tsiolkas review (Australian edition) – carnal but tender love story marks a new era for the author’ in The Guardian (Thu 23 Nov 2023 09.00 EST).

[5] Tsiolkas 2024 op.cit: 166-70, 39f. respectively

[6] Neil Bartlett (2024) ‘The In-Between by Christos Tsiolkas review – the power of love’ (review of British pb ed.) in The Guardian (Fri 7 Jun 2024 02.30 EDT).

[7] Tsiolkas 2024 op.cit: 132f.. See 131f for lead-up material.

[8] Ibid: 241f.

[9] Ibid: 262 (note that he is still self-referring for the prose is clearly conveying his point of view of on ibid 260f.)

[10] Ibid: 143

[11] Jessica Gildersleeve (2023) ‘Christos Tsiolkas’s new novel celebrates a quiet ethics of care in a culturally noisy world’ in The Conversation (online) [Published: November 12, 2023 7.15pm GMT] available at: https://theconversation.com/christos-tsiolkass-new-novel-celebrates-a-quiet-ethics-of-care-in-a-culturally-noisy-world-213904

[12] Adam Rivett (2023) ‘Christos Tsiolkas’ new novel is the sparest, most direct he has ever written’ in The Sydney Morning Herald (November 7, 2023 — 12.00pm) Available at: https://www.smh.com.au/culture/books/christos-tsiolkas-new-novel-is-the-sparest-most-direct-he-has-ever-written-20231106-p5ehxh.html

[13] Bartlett, op.cit.

[14] Silcox, op.cit.

[15] Tsiolkas 2024: 47

[16] Fror examples see ibid: 44, 52, 132.

[17] Ibid: 288

[18] Ibid: 157

[19] Ibid: 25 The transliterated Greek term ‘pousti’ (from πούστης) is a derogatory term equivalent to queer but also used of any male considered distasteful.

[20] Ibid: 60

[21] Ibid: 81

[22] Ibid: 87

[23] Ibid: 154

[24] Ibid: 270

[25] Ibid: 281

[26] Ibid: 299

[27] Ibid: 318

[29] Ibid: 283