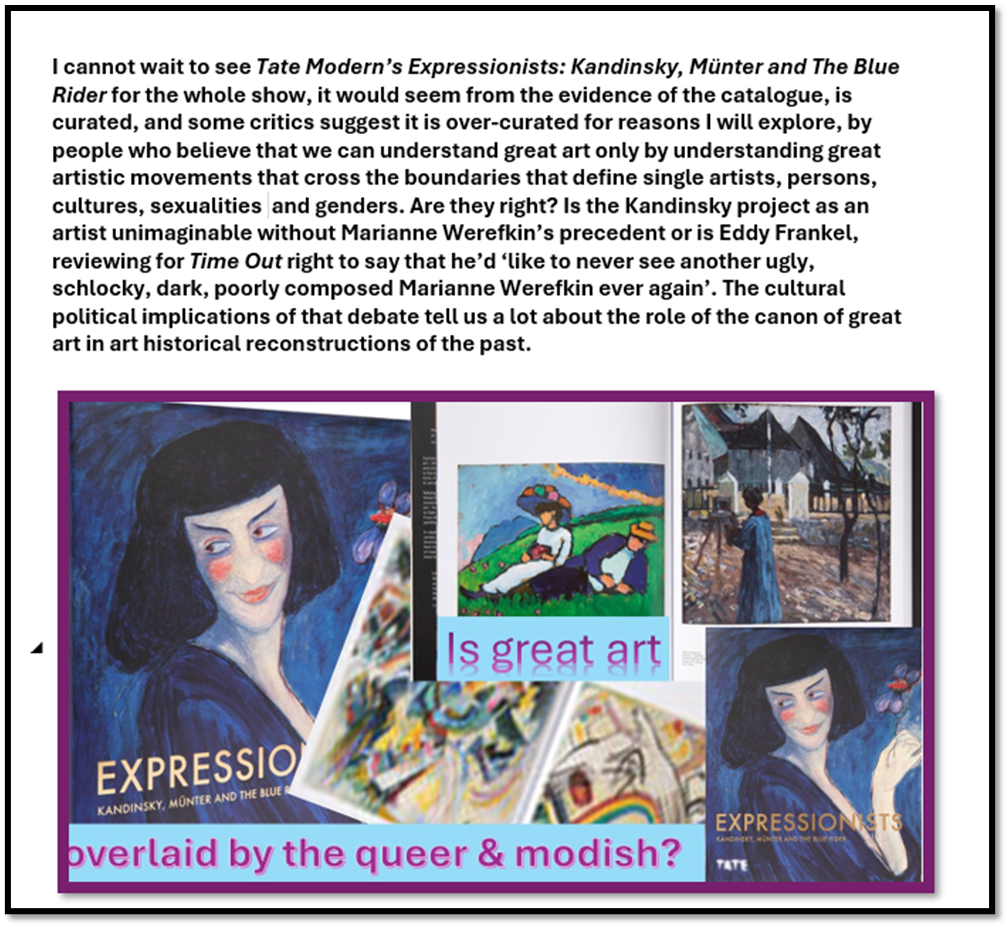

I cannot wait to see Tate Modern’s Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider for the whole show, it would seem from the evidence of the catalogue, is curated, and some critics suggest it is over-curated for reasons I will explore, by people who believe that we can understand great art only by understanding great artistic movements that cross the boundaries that define single artists, persons, cultures, sexualities and genders. Are they right?

The curators of the Tate Modern’s Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider show suggest that the trajectory of the Kandinsky project, even confined to his own artistic output, may be unimaginable without Marianne Werefkin’s, to name the main outlier for most critics, precedent or those of others, especially Gabriele Münter. Yet Eddy Frankel, reviewing the exhibition for Time Out, says that he’d ‘like to never see another ugly, schlocky, dark, poorly composed Marianne Werefkin ever again’.[1] Some other critics go as far as to extend this prohibition to Münter. Is he right to see the distinction he draws between lesser negligible figures and the great artists that entered the canon by leaving them behind. The cultural political implications of that debate tell us a lot about the role of the canon of great art in art historical reconstructions of the past.

It is difficult not to notice that, alongside a rather prurient dislike of the boundary-crossing projects named Der Blaue Reiter and Der Sturm movements as opening the doors by commitment to art that questioned iconic belief systems supporting the hegemony of a patriarchal view of Great Masters of art – stolid, grounded in sacrosanct myths of the nation and supporting the great truths of a stable system of sex/gender and sexuality, led, of course by male Masters, great Masters. Even in the tentative longing for cohesion in Eddy Frankel’s review opens him up to demonstrating preferences that might prefer to exclude things that allowed themselves ‘not to be very good’, that are difficult to distinguish from the happenstance misogyny of fuddy-duddies of art history locked into the reproduction of a traditional canon, with the odd update. He mourns the decision to put in lesser paintings of Klee and though he understands its rationale despairs somewhat subliminally at its lack of coherence of a movement that in theory, if less in practice, shattered conventional boundaries and hierarchical binary thought systems:

The Blue Rider was a Munich-based art collective revolving around Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter, the original modern art power couple. Artists from countless backgrounds and disciplines congregated around them from all over Europe, drawn to their borderlessness, openness, genderlessness. The Blue Rider embraced everything new. As a result, there’s not a whole lot of aesthetic cohesion going on here. … The Blue Rider was a mishmash, a hodgepodge, and sure, a bit of a mess. / And that was by design. Because what was happening in 1911 Munich was the forging of new possible paths towards the future. They were figuring things out.[2]

In the descriptions of the incoherent in the exhibition by his lights, Frankel covers the downplaying of that most destructive of hierarchical binaries good or bad art:

… everything was possible. Including the possibility of not being very good. I’d like to never see another ugly, schlocky, dark, poorly composed Marianne Werefkin ever again, Franz Marc’s emo-spiritualism feels like futurism robbed of its power, Alexey Jawlensky’s work is pretty heinous, Münter’s own photography isn’t half as interesting as they tell you it is and they’ve managed to pick some of the ugliest Paul Klee paintings he ever did. None of which is helped by the exhibition having so many half-arsed areas of focus. Again, a bit of a mess.

It plays a game this critique – of understanding why the queering of standards was important and necessary, and supporting it by rather gauche expressions of the necessity of standards to set against the intrusion of ‘so many half-arsed areas of focus’, Whilst you can imagine art historians being in agreement, you can’t imagine them expressing the intrusion of the experimental under the heading of the ‘half-arsed’. It takes an intelligent review from the i newspaper, not so much as to balance the Time Out choice of attempting to say things with well-signposted populist vulgarity, as to assert the necessity of revising our view of things we call art that we label as ‘not being very good’ but by truly looking at it to see what is there before we make such judgements with the nuance required. Here is Hettie Judah on Werefkin’s 1910 self-portrait (see below) from the exhibition and a good example to test Judah’s perception against Frankel’s.

Marianne von Werefkin, Self-portrait I, c.1910 (Lenbachhaus Munich) (Image: Tate Modern)

Judah describes this portrait rather than generalises about the composition of her paintings as a whole, although one can imagine Frankel saying that the portrait is ‘a bit of a mess’ when asked. Judah says of it that the figure represented:

… is positively diabolical. Set against a vibrating blue and green background, her head is framed by a deep crimson hat which is matched to her lipstick. Werefkin glowers beneath dramatically arched brows with monstrous, reptile eyes – deep red irises ringed with turquoise, colours juxtaposed to give the unsettling impression of intense movement. The effect is deliberately challenging.

This she-devil is not how she was seen by others. In the same period Münther painted her posed in an almost identical position wearing a dramatic flower-laden hat, and Erma Bossi portrayed her as an elegant society hostess swathed in an embroidered shawl about a sweeping sugar-pink robe. Werefkin’s desire to startle, then, was calculated – a salvo against expectations.[3]

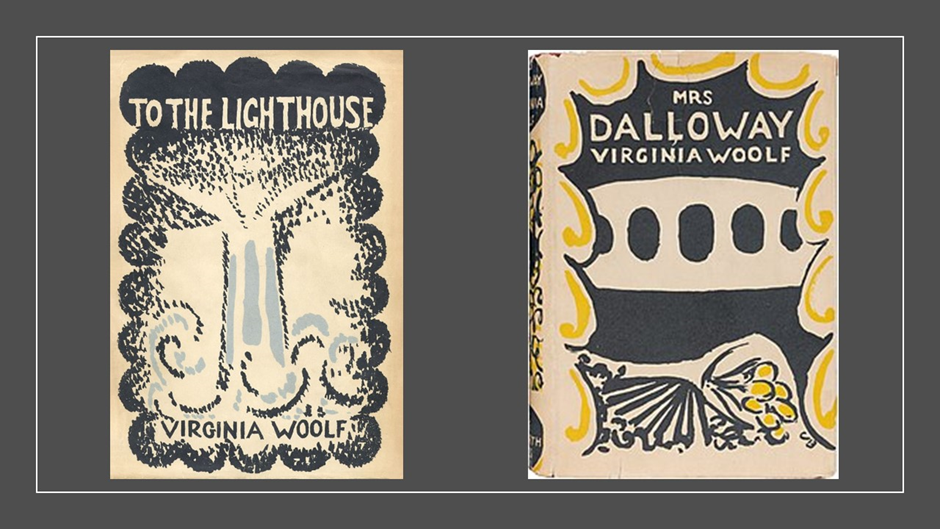

Laura Cumming in The Observer too, sees the painting as directed at a viewer, a distinctly male viewer (with the authority of Werefkin’s writing behind that reading), with an almost violent challenge to their expectations of womanhood: ‘With this painting, she declared, the artist had caught “the male gazes that call for a slap”. Cumming continues with a warm welcome to a mode of expression in Werefkin stronger than the ‘wall text’s prissy assertion that Werefkin is confronting gender stereotypes”’.[4] But these characterisations of female art in terms only of the ‘male gaze’, or indeed ‘gazes’, seem not to take the paintings as seriously as one takes male art, on its own terms. For instance to make her into an ‘elegant society hostess’ is surely here as heinous a simplification, whether it be that of Bossi or Judah, as would be doing the same with the art Virgina Woolf created in making the person and contexts of Clarissa in Mrs Dalloway or Mrs Ramsey, especially as seen by artist Lily Briscoe, in To The Lighthouse.

For that reason I think we need to avoid seeing the art of Werefkin as only about feminist retort to men for the point that she is ’ confronting gender stereotypes’ gets nearer if not entirely to the point of the radicalism of her expression of the world impressed her. The words I use here are hers, for the catalogue quotes her clarion expression of the principles of expressionism well before Kandinsky: ‘All true art is constituted of the impressions received and the expression that derives therefrom’.[5] It is easy to oversimplify this point, for impressions are multiple and cannot be conveyed directly, as the Impressionists, it could be thought, assumed since they felt impressions caused by external causes – how light and shade fall matched invisible impressions received in the sensations and feelings of the viewer who turns them into art. In Werefkin, there is a kind of insistence that feeling and sensation displace concentration on what is visible to what is felt to motivate and drive the artist whilst at the work of expressing the interaction of themselves with the world, a kind of frottage producing a ‘spark’ as she called it,[6] and making the process and materials of art primary over concepts like prescribed design, the approach to art of Raphael according to Vasari, and called ‘disegno’. Vasari offered the alternative ‘colore’, associated with Titian by him, but colore is about more than expressive colour.

In the self-portrait of Werefkin we notice especially the unsettling refusal to distinguish between person, natural fauna and flora, the supernatural and the flow of colours that helps establish and disrupt these categories. Hence the names critics try to describe the figure: for instance, Judah’s ‘she-devil’ and Cumming’s use of forms of words like ‘wild’, fierce’, and her description of the painting’s look of ‘yellow light flaring down one side of her face, eyes the lurid scarlet of some sci-fi monster’. After all , art that tries to ‘figure out’, to use Frankel’s casual language, what things are beyond the social categories and hierarchies of discrimination that social norms impose on them (such man and woman binaries, the cusp between natural and unnatural, or even supernatural). Categorical thinking is inevitably, at least partially, submerged and struggling under waves that help to create, alongside and beyond the necessary destruction of the barriers to the potential to become rather than just to be what we are to ourselves or each other. Things and persons in expressionism emerge out of the chaotic contexts that helped form us rather than mimic a prescribed and delineated being within lines drawn and traits written by others.

Moreover, if you look above at the Werefkin self-portrait again the issue is not merely the interplay of colours and their overlay of each other. Lines are not absent but they are not consistent either in delineating figure or elements in the figure’s aura. And it is as much aura as it is a background to the figure – it comes from an intuited interior of figure and viewer in interaction, that refuses to look like that of an unmediated impression but takes on the virtues of the medium both as materials and process. The surest example of this is the representation of waves or frequencies (not unlike Virginia Woolf’s interest in these). Waves have intervals that reproduce the dynamism of their creation. The best example is the multicolored hair under Werefkin’s hat that forms settle waves sometimes but at times projects out into the surroundings as if merging with the painterly activity recorded and relivable there. In the surrounding wave formations are also reproduced as vertical sequences of thick painted lines or intervals. The recall of rhythmic waves in music and verse lines is important here too. Wave patterns and frequencies surely resound in the blend of colours and dabs, with straight thickly painted lines often led up by a rising brushstroke. I think from here comes the play with the analogies between male and female. Hard lines and pronounced facial and bodily features (the very thick long neck for instance) interact with the softer performativity of the interior person as the colours of unreadable passion and perform a role of comment upon not just gender but ‘biological’ sex categorisations. Reds go from visceral animal ferocity to the softness of a blush on a thick neck.

Art is being redefined, as Werefkin suggests in a favourite quotation from her in the catalogue, which defines the quality of a new artistic project as ‘the absence of art, it is heart that empowers the brush’.[7] The stress on power uses the heart metaphor in a strong way. Hearts beat with the pulses of a dynamic flow, in a wave frequency of course as sound and motion, and we feel the heat pushing and pulling the brush in its strokes, dabs and washes of overlaid colour. It is the active and passive energy of the painting hand that both drives and inhibits the process of art, modified by the qualities of the media – the paint, the paper and so on. Bodies are, in the thinking of the time, androgynous across a range of traits. To wish not to see another Werefkin and describe her as he does, Eddy Frankel refuses to see her in ways that alone will describe how she influenced authorised artists in whose shade she lies. The director of the Kunsthalle Bremen (Bremen Art Museum), Gustav Pauli, who knew her, even employs the words I use above to describe her as ‘the center, the transmitter, as it were of waves of force that one could physically sense’. Her nicknames emphasised the non-binary nature of her force : ‘Amazon of the Blue Reiter’, ‘horsewoman’, ‘noble wild lad’ and ‘manwoman’. [8] These nicknames had substance from her intellectual studies, attending lectures by Vladimir Solovyov in Moscow in the 1890s. That philosopher wrote a book named The Meaning of Love (in 1893) that focused on aspiration to ‘the unification of the masculine and feminine to achieve the androgyne, a consummate being that would unite features of both genders’, based, in part, on the notion of the ‘third sex’ in Magnus Hirschfield’s sexological work. The artist described themselves thus: “ I am not man. I am not woman, I am myself’.[9]

The view of her by Münter presents us with an image that is more a rhythmic icon where a defined androgynous face, though more subtly so than in the self-portrait by Werefkin gazes directly at their viewer. The sitter appears to emerge facially from the process of being metamorphosed into a design motif, her body is turned into abstract shapes through each section of which heavily toned colours flow and coagulate irrespective of any attempt to achieve an illusion of volume unlike the face, with kits green and red wash tones that do most of the structuring of that volume. It is too beautiful to categorize.

Portrait of Marianne Werefkin, 1909 by Gabriele Münter

Werefkin’s most obvious expression of the androgynous ideal is her 1909 painting The Dancer Alexander Sacharoff, painted in tempera. Non-binary identity was a living reality for Sacharoff, for their art was their will to beauty, as they and Werefkin articulated via Schopenhauer’s notion of the will as the tool of self-consciousness that, in its performance as art, has ‘absolute mastery of the limbs of the body’. The portrait of Sacharoff shows the will to be a motif of unisexual non-binary (and indeed queer) love.

Marianne von Werefkin, The Dancer, Alexander Sacharoff, 1909.

In performance what is article and what is nature is an unnecessary binary distinction, as indeed here is the binary of male and female. The painting vibrates across its fuzzy boundaries that demarcate figure and background, the natural and painted, especially in the ambiguous possibilities of a made-up face becoming a blush of self-consciousness at being seen by a lover or by an audience. This is not a clothed figure but one that is in the process of either clothing or unclothing, the proc ess by which it happens in the rhythmic vibration of the tonal blues. The right side of the Dancer’s costume dissolves into its surrounding space despite its obvious presence as delineated in the neckline of the garment. As boundaries of things dissolve so does the sex/gender relationship formulations of groups across boundaries of time and space, as in the musical harmonies and discords of Arnold Schönberg’s music. Gabriele Münter tried to paint what listening looked like, using the harmonic and discordance in play in the design, in the contrastive intensity of colour patches , in the ambiguous flow of things into other things:

Gabriele Münter, Listening (Portrait of Jawlensky), 1909 (Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957) (Image: Tate Modern)

At this point I feel tantalized enough to see the exhibition myself in July. A key note in boundary-crossing for these artists was between the genres and modes of artistic expression that caused works of art to ape the modes in analogy with another art form, each in its appropriate and historically acquired repertoire of media, whether it be the dance of Sacharoff, the music of Schönberg, the meta-discourse of art, the spiritualisation of everyday life and the design of living spaces and expressions of folk nationality as variations in an equality of transnational humanity. The catalogue is fulsome about all this but I think it better to leave comment till I see the exhibition. For instance the use of prismatic viewing media is used in one room for some works and the music of Schönberg played in another. Hettie Judah describes these curatorial innovations with more than irony:

A little over midway through this show, three rooms invite us to experience individual paintings in different ways. Two works by Schönberg play in a dark chamber hung only with Kandinsky’s Impression III (Concert) (1911), which was made in response to a performance of the composer’s work. Transcendent yellow floods the painting, saturating the gaps between pianist, string players and audience, who become bound together in an energetic arrangement of abstracted forms.

…

Such a shame, because they are preceded by one of the exhibition’s strongest displays, a wall of paintings tense with latent energy by Marc.

The attitude is clear. Art curators should stick to their traditional role and stop messing about with how we see the canon of ‘great art’ despite the fact that some of it grew out movements that saw the relationship of art, nature and facture (or making) differently from the tradition. My bias is to go with the curators who are, it would seem to me from the catalogue, attempting to restore perspectives on the world on general that were new in their time and to some extent lost later, until refound in recent times, together with ways of seeing the art it produced. For a movement like The Blue Rider the aim is not to give birth to a Kandinsky or Klee (and Marc on the margins) but to explore each other’s contribution and to attempt an art that had elements of cooperation. Many critics are snooty about Münter’s photography, but the catalogue alone has convinced me that to re-see the relationship of photography and other art in a Blue Rider perspective is more than worthwhile.

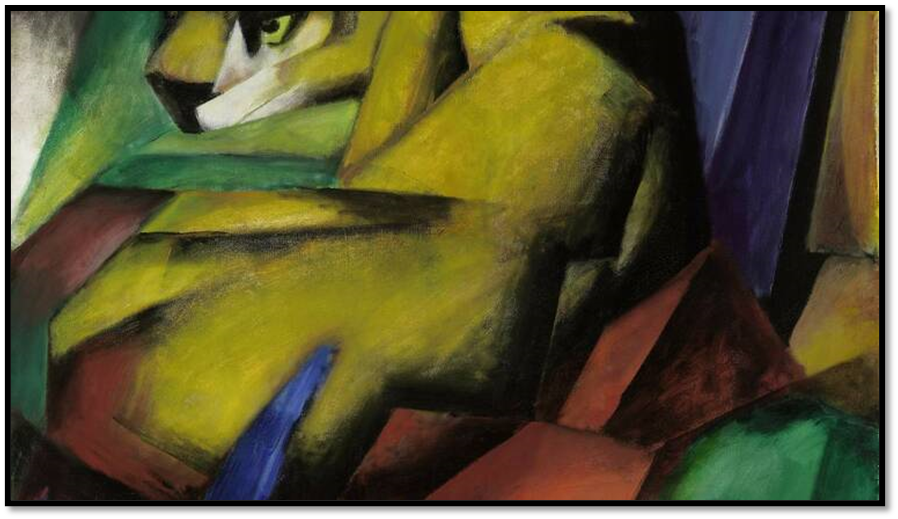

Franz Marc’s explorations of the cusp between nature and art, animal and human facture is clearly analogous to the things we have seen in Werefkin, as in this fabulous tiger where form is a concept blurred between mimetic and abstract aims:

Franz Marc, Tiger, 1912. Lenbachhaus Munich

The Tiger alerts and awakes us to form and figure while confusing them. Of course, I want to see great late Kandinskys – here is a favourite painter in my eyes – but how good to see him arising from the attempt to derive form from folk narrative as in The Couple Riding, where the Blue Rider iconology together with Germanic myth forms a link to the growing love between Kandinsky and Münter. And how exciting to see the dry rigour of French pointillism metamorphosed. All serves the role of queering art in the interests of equality and diversity, which are not in opposition (not at all) to quality, but rather refine its criteria.

Wassily Kandinsky, Riding Couple, 1906-1907 (Lenbachhaus Munich, Donation of Gabriele Münter, 1957) (Image: Tate Modern)

I never thought I might cite The Tatler, but Harriet Keane writing there, at least displays an openness that critics in the national newspapers seem not to dare to share, lest it be seen as naïve. There is such willingness to learn in this final paragraph. It humbled me. It ought to humble national press writers who oft seem to want to show that they need learn nothing at all.

What the exhibition captures well is the sheer breadth of The Blue Rider group. It is multifaceted: there is photography; art criticism; experimentation with light; and opera music. Then there are Kandinsky’s handwritten letters and a battered copy of The Blue Rider Almanac: a publication of art criticism by the group. These personal touches enable this exhibition to be a mesmerising window into The Blue Rider world. I left feeling as though I’d had a masterclass in colour, form and abstraction.[10]

I visit this exhibition with husband Geoff, and dear friend, Catherine at 3.30 p,m, at the Tate Modern. I am looking forward to it very much and will report back if I have more to share.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Eddy Frankel (2024) ‘Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider’ in Time Out (Tuesday 23 April 2024) Available in: https://www.timeout.com/london/art/expressionists-kandinsky-munter-and-the-blue-rider

[2] ibid

[3] Hettie Judah (2024) ‘Expressionists, Tate Modern review: I wanted to lick Kandinsky’s paintings’ in The i newspaper (April 24, 2024 6:00 am(Updated April 25, 2024 11:47 am)) Available at: https://inews.co.uk/culture/arts/expressionists-tate-modern-review-wanted-lick-kandinskys-paintings-3019947

[4] Laura Cumming (2024) ‘Expressionists … – bringers of joy’ in The Observer (Sunday 28 April 2024).

[5] Niccola Shearman (2024: 176) ‘Werefkin and her Salon’ in Nicola Bion (Senior Editor) Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider London, Tate Publishing. 176f.

[6] Ibid: 176

[7] Ibid: 176

[8] Cited Charlotte de Mille (2024: 92) ‘Marianne Werefkin – ‘Noble Wild Lad’ in ibid: 92f.

[9] Ibid: 92

[10] Harriet Kean (2024) The Tate Modern’s bold and bright exhibition is a mesmerising window into The Blue Rider group’ in The Tatler (online) (20 May 2024) Available at: https://www.tatler.com/article/expressionists-the-tates-bold-and-bright-exhibition-review

One thought on “I cannot wait to see Tate Modern’s ‘Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider’ for the whole show is curated by people who believe that The Blue Rider movement was about crossing the boundaries that define single artists, cultures, sexualities and genders. Are they right?”