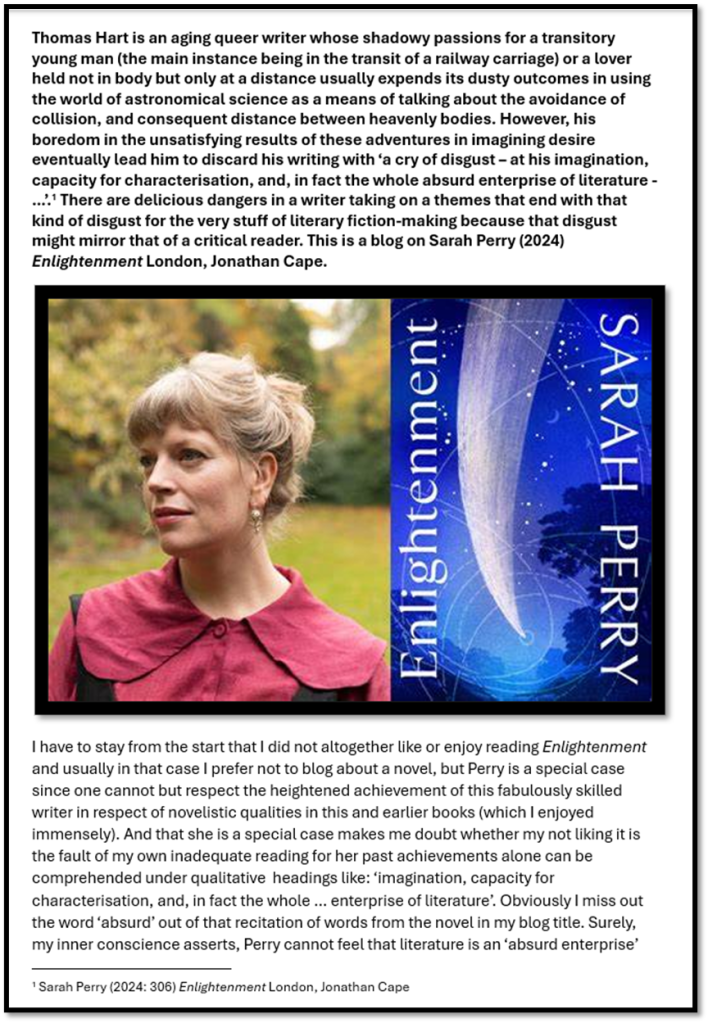

Thomas Hart is an aging queer writer whose shadowy passions for transitory young men (the main instance being in the transit of a railway carriage) or a lover held not in body but only at a distance usually expends its dusty outcomes in using the world of astronomical science as a means of talking about the avoidance of collision, and consequent distance between heavenly bodies. However, his boredom in the unsatisfying results of these adventures in imagining desire eventually lead him to discard his writing with ‘a cry of disgust – at his imagination, capacity for characterisation, and, in fact the whole absurd enterprise of literature – …’.[1] There are delicious dangers in a writer taking on a themes that end with that kind of disgust for the very stuff of literary fiction-making because that disgust might mirror that of a critical reader. This is a blog on Sarah Perry (2024) Enlightenment London, Jonathan Cape.

I have to stay from the start that I did not altogether like or enjoy reading Enlightenment and usually in that case I prefer not to blog about a novel, but Perry is a special case since one cannot but respect the heightened achievement of this fabulously skilled writer in respect of novelistic qualities in this and earlier books (which I enjoyed immensely). And that she is a special case makes me doubt whether my not liking it is the fault of my own inadequate reading for her past achievements alone can be comprehended under qualitative headings like: ‘imagination, capacity for characterisation, and, in fact the whole … enterprise of literature’. Obviously I miss out the word ‘absurd’ out of that recitation of words from the novel in my blog title. Surely, my inner conscience asserts, Perry cannot feel that literature is an ‘absurd enterprise’ but rather a highly meaningful one given the evidence of her intense writing here and elsewhere. I think however that this novel plays on the cusp of those extreme versions of what literature might be (fantastically absurd or imaginatively sublime) and on purpose.

To illustrate that I want to use the literary judgements of Beejay Silcox, with whom I often agree, in The Guardian, because her review captures the problems I felt as I read. It does so however though it does so with a hint of the same admiration I feel, for Silcox that is admiration of Perry’s ‘gorgeous prose’, that Silcox claims allows Perry to be forgiven for ‘all manner of narrative sins’, given the ‘astonishment’ conveyed by that prose, of which she quotes superb examples. In particular, Silcox marvels at how the conduct of possible love matches is aligned to a theme of cosmological physics and astronomy sublimely described, despite the fact that there is something clichéd about the romantic love matches themselves. I knew exactly what Silcox meant in saying: ‘I was charmed by the book’s cosmic strangeness, but bothered bit its queer clichés . It’s so wearying to confront yet another tale of exquisite, chaste gay loneliness’.[2]

To some extent I would question Silcox’s choice of the word ‘chaste’, for Thomas Hart clearly does have a life he prefers to be unexamined. The ambiguously heterosexual man he falls in admittedly ’chaste’, love with (James Bower, whom I like to think of as a tempting Spenserian ‘Bowre of Blisse’), even sees Thomas, with an interest that ‘was more or less anthropological, as if the other man were the citizen of a province of which nobody else had heard’.[3] This is lovely stuff – a lot of work is done in that ‘more or less’ in exposing the ‘cocktease’ role that James bower plays, but the point is the pretence of the ‘otherness of queer men’ and the silence arising from convenient ignorance of that ‘otherness’. In fact Hart’s non-normative love-life pokes out of the novel a little earlier when we see him with a ‘in carriage D of the 10.42 from Liverpool street’ submitting ‘dumbly to the affection of a red-haired young man with whom he’d spent the past three days’. No-one, I believe, is meant to believe those last three days were chaste, just ‘unexamined’ and undescribed. Despite the young man’s attempt to appropriate his elder ‘lover’, Thomas reflects that he is of mere passing interest, appalled by this young man’s open sexuality and ‘thoughtless touches’.

He survived, as he put it to himself, by dividing his nature from his soul; so he left his nature in London on the station platform, and picked up his soul in Aldleigh, as if it were left luggage. [4]

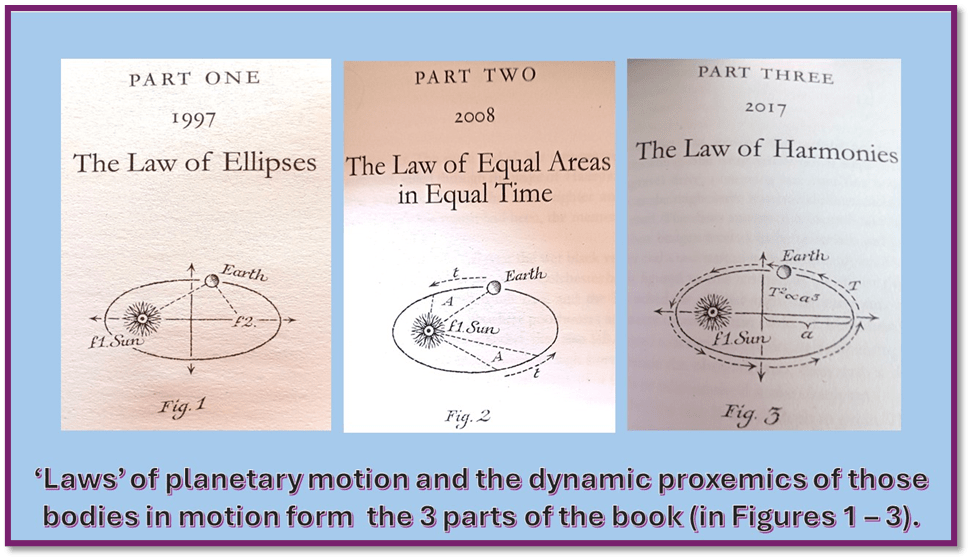

It is rather inconvenient that he also has a home in Essex at Aldleigh near Thomas and hence Thomas brushes him off with an “I’ll leave you here’ on Aldleigh station platform.The chaste relationship with James Bower at the centre of this novel certainly does not have much bodily touching in it but, when touches happen, they are not ‘thoughtless’. Yet a lot of the novel has to be passed through till these touches are chastely offered with a hint of submission on Thomas’ part. The lack of any mutual proximity between their bodies is in parts of the novel somewhat like an example that people in the novel often invoke; the inevitable distances between celestial bodies in motion that Thomas describes as inherent in recurrent patterns of cyclical return in the cosmos between planets and meteors that move. The patters are needed in order to avoid astronomical collisions or close calls to possible collisions. Thomas Hart admits that his feelings for James Bower, unreturned by the latter, have caused him pain. Their conversation is touching without the agents in it ever actually physically ‘touching’ or feeling conscious of doing so:

“…it seems to me almost a humiliation: after all this time I want to touch you, because I never did.”

“You never did”, said James. He was looking with fear at the lamenting moon. “you never did. But do you want to, even now? You can” – he seemed to be leaning out of himself – “I’m just here.” He breathed as if the air were thin. His lips were red. The buttons on his coat had come undone and he looked at Thomas …

This exchange is almost breathless up to this point in its capacity to create in its rhythms and caesurae the feel of the book offering up to Thomas the long-wished-for outcome of his hot desire, the prose even undresses James slowly, starting with those buttons. It is sensual this prose. It shows how Thomas’ body feels its way to a possible touch. At least it would do so if the final sentence I break into above were not such a deliberate come down, falling dead at its full stop, denying the mutual desire that a reader intuits that they are both feeling. The rhythms of excitement that seem to have arisen in James even pop his buttons, one thinks as one reads, until, that is, the sentence completes its own sexual suicide: ‘The buttons on his coat had come undone and he looked at Thomas with an elated will that had no desire in it’.[5]

I have to say that Beejay Silcox may overegg how much this constitutes ‘queer clichés’ at work or just ‘exquisite, chaste, gay loneliness’, for those kinds of story rarely animate the loved object, even the ‘straight’ object of a gay male crush as does the scenario above. It is masterful in its controlled writing and ability to convey sensation. I think this is possibly because Silcox overstates the idea that the book is more decorous than Perry’s earlier earthy novels, or A. S. Byatt’s Possession or John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman, because it ‘a study in unrequitedness (star hunters look to the heavens, not down into the lusty muck)’. This cannot be accurate for the whole point is that the ‘stargazers’ in the novel, Thomas Hart, the journalist pushed into an amateur astronomical science by his editor, and the long-dead astronomer, (and unrequited adulteress-lover also), Maria Vădua both relate to the muck (Vădua’s marble statue is dug out of the mud at the bottom of the lake and has to be washed back to pristine virgin marble) as well as the stars eventually, and this is a strength of the novel. Yet it is true that the attempt to link both’ unrequited’ lovers to the motion of the stars is a weakness of a novel for ever straining to do that: to invoke what Silcox calls the ‘capriciousness of the stars’.

There is no doubt that the stars are brilliantly interwoven into the study of bodies in motion, that nevertheless do not touch, and for whom it might be disaster that this should happen, for stars are ordered by pattern rather than being capricious in an anthropomorphic manner. But it is untrue when the two male potential lovers say that one never touched the other for Hart does it when explaining the orbit of celestial bodies: ‘With a gesture inconceivable in any other room, and from any other man, he lifted James’ finger and described a pale curve in the centre of the circle. “This is what they call Barnard’s Loop”, he said’.[6] The implication is clear – the grasping of another man like that is ‘inconceivable’ except in those particular circumstances because it is an intimate touch that both, for different reasons, would have assumed prohibited.

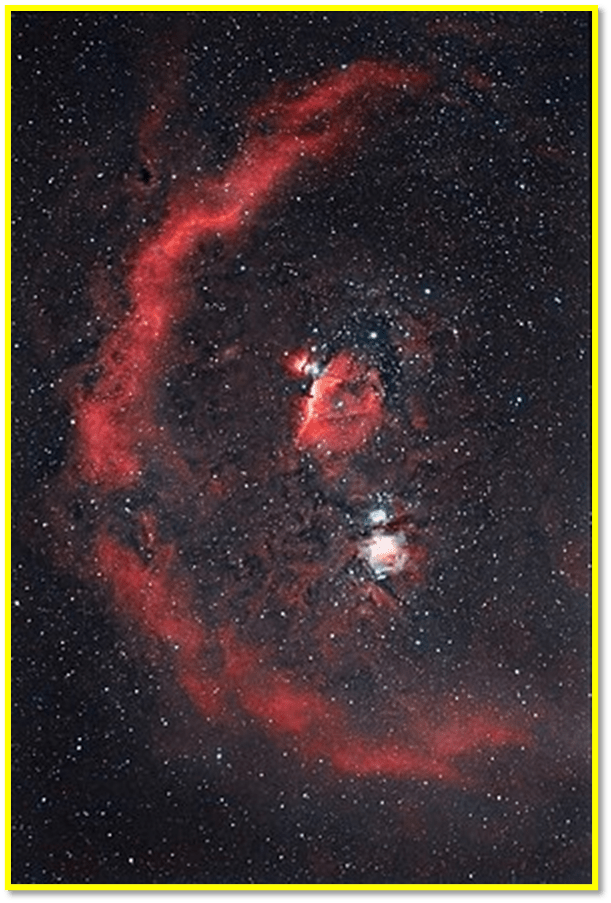

The astronomical Barnard’s Loop in the constellation Orion serves a purpose for Thomas Hart.

Loops, cycles, ellipses are all patterns of celestial bodies in motion, and the novel makes it clear that intentionally or otherwise, Thomas Hart regularly creates analogies, and from the time of his early dispatches in The Essex Chronicle, between the motion and mutual orbit of his own and other people’s bodies in grouped dynamic patterns, motivated by unknown forces. To him it seems part of his nature – something inexplicable in what ‘moves’ him, where to be moved means both to be in motion and in emotion.

From: On the Motion of Bodies In Orbit, Thomas Hart Essex Chronicle, 28 March 1997

Sometimes I think of my own body in motion. What moves me on? What moves you? I suppose I could tell you what kind of sun draws me down my orbit, but there must be other forces at work that I can’t make out.[7]

In Beejay Silcox’s otherwise admiring glance at Perry, the whole cosmic game in the book is just a device to motivate sexual and romantic love stories: ‘a narrative she loves, and a spectacle she wants, and thwacked them together out of astronomical necessity’. Well maybe! That would certainly explain why I feel the book over-long and over-enthusiastic about its astronomical way of telling a human story about attraction and repulsion in motion ruled by known and unknow forces.

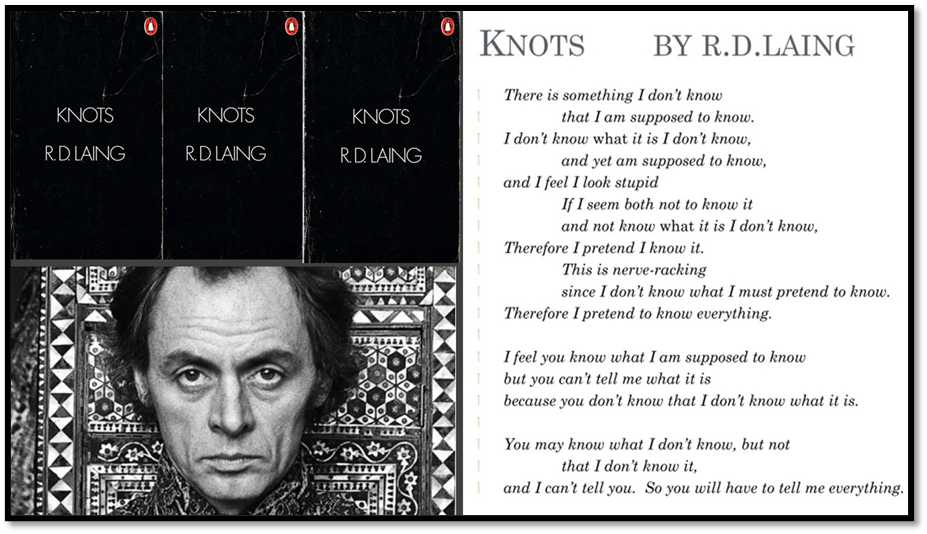

Yet I wonder too whether Perry needed this machinery, which clanks to my ear sometimes, because whilst establish a group of people who believe in laws that govern our proximities from each as bodies, she also wanted to undermine them. I think that because of an intriguing section of the book on another metaphor for relationship, that used by the guru psychiatrist and poet R.D Laing: KNOTS.

In a book where people want to see relationships as patterns ruled and governed by laws, Laing showed us a world of relationships where we all tie ourselves into knots by trying to knot each to the other in social constructed groups, like families and marriage, creating monstrous contradictory double-binds that may create attachment with the felt advantages of that but also inexorable stresses that ensure some of us die, quite literally, in order to escape them. In the novel the idea of KNOTS is elaborated very late towards its end, when the attachments between the characters are loosening. Hart attends a folk ritual that he writes, since he must write it up for the Essex Chronicle, is ‘said to be an ancient Essex rite marking the autumn equinox, I have my doubts, …’– . Astronomy is undermined by false folk ritual here despite him quoting a Saxon precedent as he looks at ‘the length of garden twine tied round the wrist of the man seated at the left’, who assures him it was ‘all made-up’.[8]

In this milieu, Thomas Hart finds his gaze locked into that of another man, whom he thinks he does not know who tries to keep him by his side on the pretext of meeting Grace Macaulay, though the mutual actions of both men are described as if they were coded attraction. The man has ‘a curious secretive look, as if admitting a sin without guilt’. Thomas noticing what is boy-like in the man notes ‘the appeal of that blue gaze now turned on him’.[9] Only because the word appeal is ambiguous, do we allow ourselves to miss the coded talk. The man is Nathan whom Grace Macaulay when both were younger but he more so than she, of whom more later, had wanted to bind to herself but who had escaped that bond and was now married to another. Grace arriving on the scene, more ambiguous talk is made of being knotted until she is implicated in the knotting. Thomas’s view is obscured by a knot od dancers who move in ‘stately circles’ and in ‘practised concourse; like stars in orbit, but whose movement is determined by knotted threads:

Dazed by beer and music, Thomas saw all the threads that bound them in varieties of human bondage – knots made of habit, blood, resentment, desire offered and withdrawn, love met and not met, all tying and untying as he watched.

Noticing that he is alone in all this, Nathan, abandoned by Grace now, is also alone: ’With pity amplified by the remembrance of desire, he came nearer the younger man, and put his hand in his pocket, hoping to find a bit of string to join their ruined bodies’.[10] Sentences like these create ambiguities – in whose pocket does Thomas seek string? The ambiguity can’t be escaped, and what knot will tie him now to a man for whom desire, from him at least, has not been felt before. The KNOTS theme introduces random selectivity into the otherwise lawful and stately apparent move of bodies around each other and undermines the theory of attraction and repulsion by natural or cosmic law. And that is the theme Silcox sees but is wrong to attribute to astronomical themes alone, without this random element. The simplest version of the theme is very near the end, where Thomas summarises his learning as if from one man (we assume it to be the now dead Bower, but which might be one of many, Nathan knotted in pity, the strange spiritual father and wanderer Dines, and, even, the red-haired man we met in Carriage D early in the novel, thus:

“I don’t understand it all, said Thomas, “I’ve wondered all my life what I owe to love. There was a time I felt that because I loved a man, he was in my debt – that he’d made me love him, and so he owed me his love in return. And now he is dead, and I can never receive even a part of what I gave! … [11]

There is a nuance then in the apparently predictable cycling and hence return of heavenly bodies – the truth being that prediction is full of uncertainty and that some returns, such as the comet first noticed by Maria Vădua cannot always be predicted for there is randomness still in the wilful and wishful motion of bodies and if we love and are loved in return, if it just a bit of luck, not the regular return of the morning star, whose identity causes such trouble in this book.

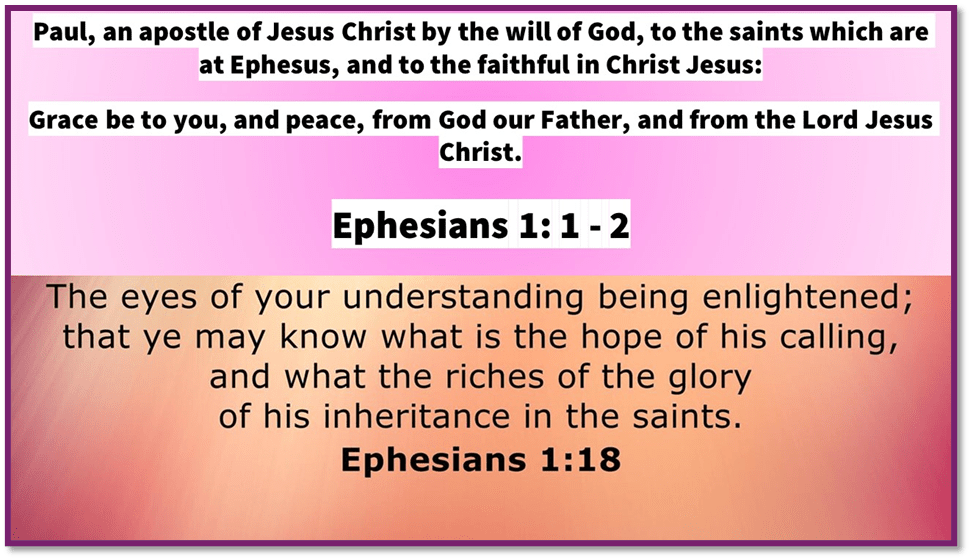

Hence I think I cannot be as severe as Silcox in seeing only a stereotype of a lonely unrequited queer lover in this novel, for Hart displays potentials well beyond the one man, whom he eventually agrees, owes him nothing and who never looked on him with desire but mere fascination that he raised another man’s ardent passion, and found it objectively pleasing with no need to act upon it. That isn’t the stereotyped queer story Silcox thinks it is. Meanwhile what the novel does show is that the persistence of homophobia can be addressed. That theme resides with Grace. For Grace rejects the oncoming ‘grace’ of understanding by staying with the precepts of a darkened religion. Hart thought like that once that, having realised that ‘he only ever wanted men’ and ‘wanted them all my life’ and spoken in his thought to the useful ghost of Maria Vădua. God, after all, and the planetary laws of who touches whom that ‘men like me lived beyond God’s grace’.[12] Herin starts the story that will implicate the character Grace, who becomes the embodiment of the good that Thomas lacks. She suddenly understands so much that ‘she blinked at the brilliance’ of enlighten ment. That Thomas, ‘is in love with James Bower’ is the enlightenment in Grace (never far from being a religious icon, that is the subject of Enlightenment.

But enlightenment fades in the dark shadows of certain forms of fundamentalist religion. Hence, we see it fade for Grace as she tries to understand her wish to: ‘

console poor Thomas Hart chilled im the shadow of Bethesda’s pulpit. It is a man he loves, she thought: Thomas is a homosexual … he was a queer, a sodomite: the Bible (she’d been told) numbered men like him among the thieves and liars that would never see the kingdom of God.[13]

As I write about this, I realise how grateful I am for the novel as Perry shares what Silcox feels is a personal story of her drift from her own parents’ stern religion. However, I still have to admit what I started with that the extremely knotted complexities of plot and character interactions and movements between letters, diaries and journalistic science was something that palled and, I have to admit , lost me, or worse, bored me as I struggled in a mental fog. It is book that I would think differently about on a second read, but Sarah Perry actually embraces the risk I have spoken about and it shows in the piece I quoted in my title and opening, wherein Thomas expresses ‘a cry of disgust – at his imagination, capacity for characterisation, and, in fact the whole absurd enterprise of literature – …’.[14]. I said that a reader must leap on this, and though it is about Hart’s written work, not Perry’s wonder about their feelings of loss in literary convolutions and obscurities, paradoxically also in the novel, Enlightenment. My own feeling is that Perry is such an expert and brilliant meta-novelist (a writer of novels partly about writing and reading novels) that she builds these escape valves for a reader into the book. I thought that on an earlier page.

Here Thomas Hart is reviewing his notes: in particular one that echoes this very novels: ‘ON THE MOTION OF BODIES IN ORBIT. ENLIGHTENMENT. THE BAPTISTS????’. Dispirited by the time his complex work has taken him he despairs of it imagining the response of patronising and unsympathetic readers at its ‘sentences unfinished and unrefined, his thoughts muddled and self-pitying’. Readers despising him is ‘more dreadful’ as imagining his body ‘discovered dirty and disarrayed’, linking the work to his ‘dirty’ secreted undiscovered life and to the lifting of the figure statue nude of Maria from a dirty lake. His cry of pain, I felt as I read, and then I felt embarrassed, but it was a meta-moment in my reading: “My God,” he said, not irreverent, “my God – will I have to go on a little longer for the sake of a fucking book?’[15]

Now, level with me, this is like – too like – the feeling a literary reader gets with a difficult book that they eel they must read. As readers commonly found, it is said, with Robert Browning’s very long poem of 1840, Sordello. As Wikipedia tells us, William Sharp in his biography of Browning, said:

Lord Tennyson manfully tackled it, but he is reported to have admitted in bitterness of spirit: “There were only two lines in it that I understood, and they were both lies; they were the opening and closing lines, ‘Who will may hear Sordello’s story told,’ and ‘Who would has heard Sordello’s story told!'”.

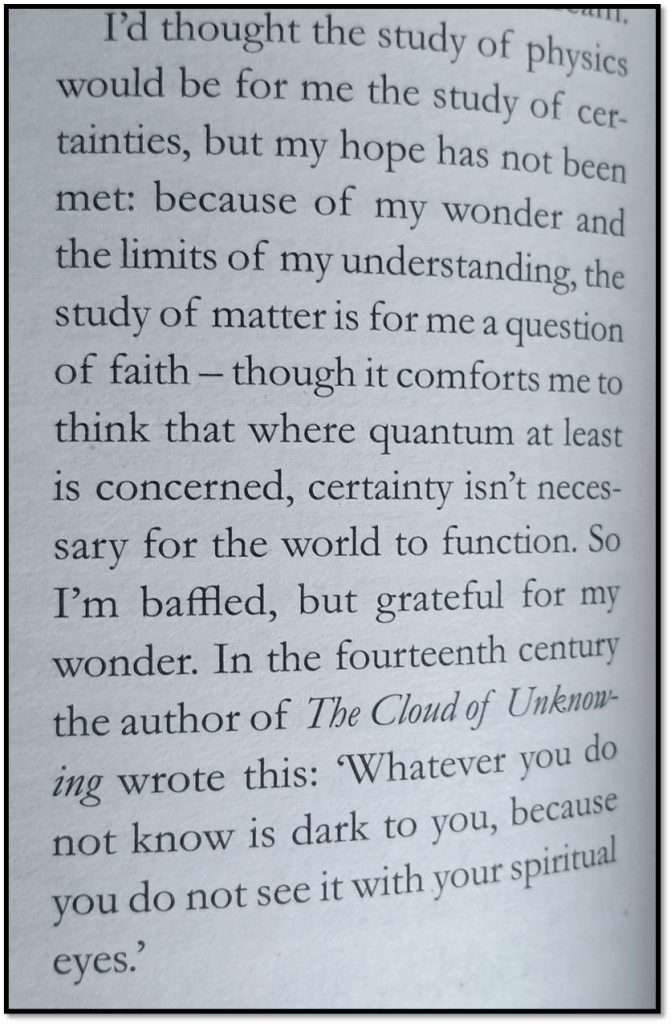

That is NOT the experience you will have of this book. If you have that response, all of the great subtleties will be missed in this book, but do not think if the reading palls that you have a faulty means of assessing good writing. Some writing bears witness to is intended obscuring of clarity and the rocky path it sets us on the way to Enlightenment. This book echoes Bunyan’s Pilgrim Progress for that reason, and characters refer to it. It echoes in subtle, and unsubtle ways, T.S. Eliot’s The Four Quartets, especially my favourite lines on ‘ash on an old man’s sleeve / Are all the ash burnt roses leave’, as well as knottier bits about time and redemption thereof. It also plays games with The Essex Serpent, Perry’s own very popular early work. After all, you truly cannot write a twentieth century entitled Enlightenment, without considering that as Hart writes in a reproduced newspaper article: ‘where quantum at least is concerned, certainty isn’t necessary for the world to function’. Here’s the whole paragraph:

There is beauty here in the obscure reference here to the medieval text The Cloud of Unknowing, an insistence that we approach God, truth and love best through obscure and clouded pathways. The idea of spiritual ‘darkness’ is what is embraced, I would argue, in Enlightenment; Endarkenment not yet being understood as beautiful. But the ide of a ‘darke conceite’ has characterised literature well before Spenser, who coined that term.

Sarah Perry op.cit: page 222, column 2

Try this novel do. Me? I need a second reading.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Sarah Perry (2024: 306) Enlightenment London, Jonathan Cape

[2] Beejay Silcox (2024: 49) ‘Divine intervention’ in The Guardian Supplement (04/05/2024), 49.

[3] Perry op.cit: 88

[4] Ibid: 72f.

[5] Ibid: 253f.

[6] Ibid: 87

[7] Ibid: 50

[8] Ibid: 327

[9] Ibid: 329

[10] Ibid: 335

[11] Ibid: 362

[12] Ibid: 48

[13] Ibid: 147

[14] ibid: 306

[15] Ibid: 246

2 thoughts on “Thomas Hart, an aging queer writer, is led to discard his writing with ‘a cry of disgust – at his imagination, capacity for characterisation, and, in fact the whole absurd enterprise of literature – …’. This is a blog on Sarah Perry (2024) ‘Enlightenment’”