At a point early in the novel Sheila English points out to her youngest son, Doll (a nickname given to him from a childish pronunciation of Donal) that to keep comp[any with his beloved older brother Cillian is dangerous to Doll. Sheila has a tendency to elevated description and warns Doll of ‘spending time with that man and his milieu’, a description at which Doll scoffs. Sheila retorts: ‘I know the sorts that do be congregating over there. That house is a wild house’.[1] Thus the novel gets a name as based on domestic venues that hold ‘wild’ sorts. This is a blog on Colin Barrett (2024) Wild Houses London, Jonathan Cape.

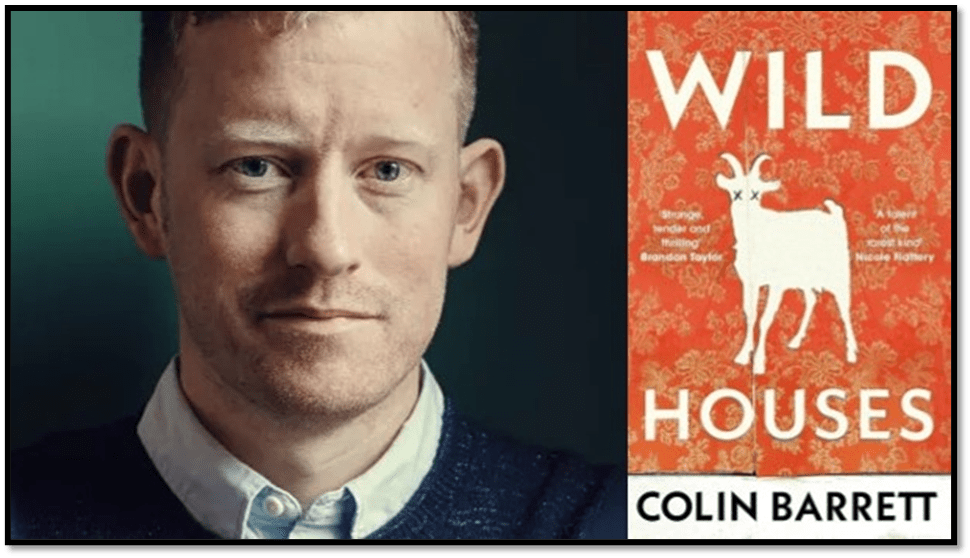

Author Colin Barrett (Photo: Rolex-Anoush Abrar) & cover of book

Max Liu, reviewing this novel for the i newspaper has a theory on the why Colin Barrett’s fascinating novel has the ‘mysterious’ title it has, saying:

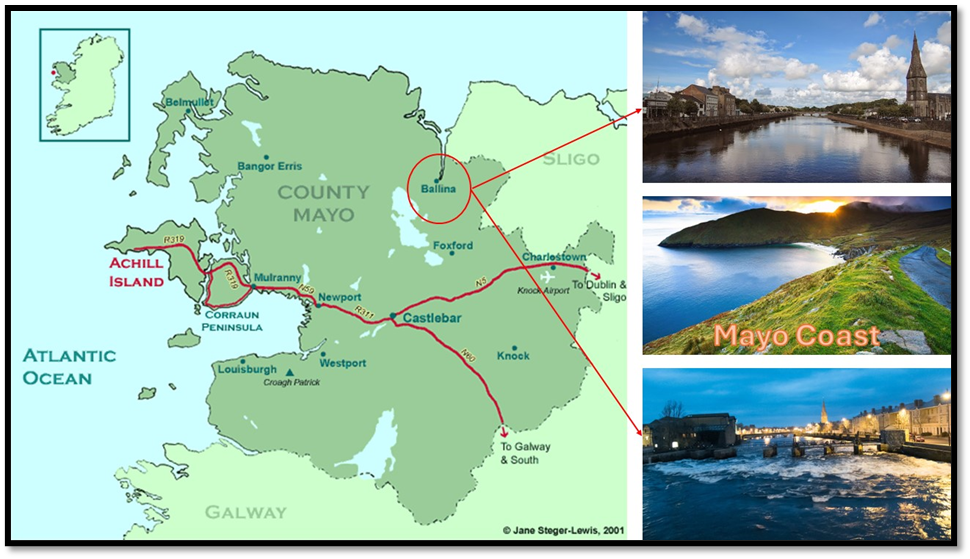

The title of the novel is mysterious but it speaks to the sense that there is an elemental wildness in Barrett’s Mayo that is stronger than bricks and mortar and can rip through the houses at any moment. That is what Dev, Doll and Cillian discover in this engrossing story. It is a place of violence, poverty and the kind of insularity that some find suffocating.[2]

It is an intriguing way in which to find an over-riding theme, but not one that describes the actual experience of the novel. Besides, Liu seems not to have noticed that the term is used is one coined by Sheila English, that coiner of fancy phrases to describe types of place and space, which I quote in my title for this blog and again here: ‘I know the sorts that do be congregating over there. That house is a wild house’. I think it is better by far to start with the implied folk definition of ‘wild house’ and to generalise that rather than to work with a critic’s sense of the meaning of the term, which imagines a force it calls ‘elemental wildness’ and lets it ‘rip through’ houses in an assumed ‘primitive’ (a word like elemental’) County Mayo. My own feeling is that there is too long a tradition of English speaking peoples finding the West of Ireland ‘elemental’, a tradition that is soundly destroyed by great Irish writers, such as in Brian Friel’s wonderful play Translations, wherein it is the English military who uproot a tradition of acquisition of Classical culture, the ‘hedge-schools’ throughout Ireland that started bottom up, rather than imposed by an élite to shore up that élite as in the English public schools.

The theme of the novel is not how wildness rips through houses in Ballina, County Mayo and its environs, but it is about a specific number of houses where the reader observes the ‘the sorts that do be congregating over there’ inside them. To call these sorts the making of a ‘wild house’ is a typical exaggeration of Sheila’s but these are houses nevertheless where the intrusion into them of working-class criminals and gangsters sets the tone of unrepentant ill-doing and the violence sometimes felt to be needed to support their activity. But elemental wildness’, it is not, it is wildness that has a certain amount of control playing over it, even if that slips, as in the most wild scene in the book, the attempted water-torture and perhaps drowning of the hostage teenager, Doll.

The almost banal genesis of violence as a tool of power, and often of the otherwise powerless, as in the case of Devereaux (known as Dev) Hendrick’s father, Vince, who also kidnaps an hostage taking kidnap and is incarcerated on those grounds. The banal violence of school bullying takes up a lot of space in the novel, explaining the path that takes Dev to his own complex mental health presentation and ‘impassiveness that enraged others’, often leading to more bullying rather than its conclusion as intended by Dev. We see just before the others get enraged and go back at him Dev just waiting for any cruelty experienced on him to end, since ‘all processes must end’, as his counselling therapist advises him:[3]

What Dev did was take what they dished out; when they got right up in his face he would go silent and impassive, submitting to each ordeal so that each ordeal could reach its conclusion as soon as possible.

I think even Max Liu cannot truly believe the novel is about literal and feral wildness, any more Dev’s deceased Mum’s dog, Georgie, behaviours are ‘wild’ because they include a lot of barking. Liu even says that though the novel has criminal and gangster characters it is hardly a crime novel, going as far as to say that, ‘fans of that genre may find the plot of Wild Houses lacking in surprises’. Instead a criminal like Cillian English seems just to have been shot into crime by a lack of opportunity or education to move beyond its youthful form of avoiding boredom. A ‘wild house’ such as Cillian creates is a weirdly playful ‘milieu’ to use Shela’s word. Here he is when he lived with Doll and the latter’s girlfriend, Nicky:

The atmosphere was that of a continuously improvised part that periodically doldrummed and never ended, contending playlists emanating from different rooms, a standing bank of smoke shimmering in seeming permanence in the sitting room, pin-eyed young ones rattling on the front door at all hours.[4]

A wild teen house-party broken up by police (in Vancouver on this occasion).

Yet this playful scene of enactment and performance, where the only things that fight are ‘contending playlists’ all battling to be heard over each other is more like mood adolescence than wild elemental behaviour, sort of reduced to the childlike in eyes of the ‘pin-eyed young ones’ who rattle doors all the time. Even when Sheila talks about and defines a wild house as I cited earlier, Doll eventually interjects that there’s ‘little in the way of congregating going on in that house these days’, and that ‘Cillian’s been keeping it low-key’.[5] Of course in the main ‘wild house’ of the text, the underlying violence against a hopelessly naïve teenage boy, Doll, is instinct with danger in the shape of the criminal brothers Sketch and Gale Ferdia, but even they and their boss, Mulrooney, withdraw when they find real crime involved, the robbing of the Pearl Country House and Pub by Cillian in order to pay Doll’s ransom, the debts of 18,000 euros created by a foolish system of storage of drugs by a site prone sometimes to becoming a lake, a ‘turlough’.

The turlough at Carran, County Clare, Ireland. The water level is high following a spell of wet weather. (Late May, 2005)

It is all pretty ‘low-key’, the crime, but with violence nevertheless implied, for no-one really is adult enough to be in control of much, least of all the Ferdia brothers, although the typical descriptions of it have a Laurel and Hardy domestic feel to them: ‘Doll tried to dart away again and Sketch slipped him into a headlock. The two staggered in a circle around the hall, knocking the coat stand over, bumping from wall to wall’.[6] As with the motion ‘wall-to-wall’ in a confined space, it is all very contained, again except for the rough play in the bathroom later. And in the end we need to remember that these three wild men are merely playing with a ‘Doll’, a boy who ‘looked fifteen, sixteen’. With a face that ‘was pale, blue-tinged as raw milk in a bucket’, like ‘any young fella you’d see shaping around the town on a Friday night, his hair full of ‘product’ and the ‘scouring bang of aftershave crawling off him like a fog’.[7] The last metaphor in that description works both as comedy and as a way of defining precisely the fauxness of youthful attempts to smell impressively ‘cool’ and masculine that are rather over the top given the real effect. Nicky’s friend Marina says the name Doll ‘suits him somehow’ and even laughs at Doll’s ‘porcelain complexion’ when she learns he got the name because he pronounced Donal as Doll ‘when I was a little fella’.[8]

A porcelain boy Doll

Keiran Goddard, reviewing for The Guardian, has a better stab at a theme for the novel, in the understanding implied by the title of his review: ‘A caper in County Mayo’, which captures the childlike fantastic in it. He says it is ‘rootedness, in every sense of the word’, but the word play says more about Goddard as a novelist than Barrett, even though the general drift is an accurate and well-written critique:

But the playfulness is only telling us that the characters are victims of small-rural-town mentality: the whole thing can describe many a novel from John McGahern and John Broderick and through Colm Tóibín to himself. In the end, like Max Liu, what the criticism I read adds to our knowledge of Barrett is merely that he is a fine writer of sentences (in the tradition of John Banville rather than James Joyce I’d say) and of, according to Goddard, ‘witty and inventive dialogue that one struggles to think of recent novels that could stand up to comparison’. Liu adds that the characters are convincing, though Liu also sees the concentration on the structure of prose sentences rather than clever suspenseful plot as almost a fault, for he says that Barrett ‘is less interested in concocting elaborate twists than in crafting fluent prose, pitch-perfect dialogue and capturing the comedy and poignancy of life in and around small towns’.

My own feeling is that the book is, at it tells us in its title, about how and why we might call a house’ that we live in ‘wild’. Houses are not safe places. Dev constantly tries to preserve a value system connected to having, after the incarceration if his father and death of his mother, his ‘own house’. This is the motivation which causes Dev to be aroused from the ‘learned helplessness’ of his character in the life story we are told in parts throughout the novel, to rescue Doll from possible drowning by the over-animated Gabe Ferdia:

The simple, clear thought came to Dev that if Gabe did not let Doll up, then Doll was going to drown. This thought amazed him in its starkness and surety. It amazed him that the kid was going to drown because Gabe would not let him up. Bit it was going to happen, and happen right here, in Dev’s house.[10]

Later when told by the Ferdia’s that Mulrooney’s interest in his house, as a storage unit for drugs and now kidnap victims, means that Mulrooney must know everything about his life, Dev starts thus: ‘“This is my house”, Dev said carefully but clearly. “Don’t be telling me what I have to do in my own house”’.[11] A house that is not a ‘wild house’ is one in which its owner learns self-regulation thereof, and the same could be said of the body, though Dev’s success in this regard hangs in the balance as this almost, but not quite, tragic-comedy ends. That the novel is about the assertion of autonomy against circumstances that plot against one seems to me certain because Dev’s story runs parallel to Nicky’s, who unlike Doll, is not going to be a doll for anyone and will leave behind forces, including Doll tied to his mother Sheila even when not to Cillian, that threaten her autonomy:

What mattered was that Doll was back with his family. And Nicky had helped get him back. All she had to do now was go inside and be with them, for just a little while more’.[12]

The intention of freeing herself in that last sentence is hopeful for her if not for Doll who will be ghosted as Dev was once ghosted for both his impassivity and the sin of having a scandalously mentally ill father: ‘Dev became a ghost, unanimously unseen’.[13] Yet, as Gabe insists, perhaps there is not even a ghost after death, even ‘clinical death’, when we neither own house or body.[14] And dead is what Martin Hendrick became instead if being a father to Dev, a man who ‘spent vast amounts of his time mired in the chair, … the chair dragged in close to the fireplace like a door closed over against the world’, staring into infernal flames with great fixity. Since that meant ‘nobody could approach him on any account, or even really be present in the room’, Dev went unloved in body and without a home of his own. Even incarcerated the chair remains, ‘consigned to the purgatory of plain sight like something left rotting in an exhibit’. Those similes are powerful. In purgatory you see the flames of Hell you are still trying to escape, locked in God’s controlling house.[15]

Another parallel between Dev and Nicky is that both have to escape a patriarchal figure, though she realises that only in a beautifully conveyed dream where, in a boat her father takes too much control, ‘taking the oars’ and ‘rowing with grave determination’. Grave determination is a power that fathers hold even when lost in Irish Catholic towns and this dream father insults her for not applying herself to help him in his task; ‘his voice clear and bitter and urgent’. When Nicky leaves Doll’s family she will be leaving behind her own too, as a chance of self, not ‘grave’ (or dead-controlled), determination. Dev is not I think necessarily as lucky unless he empowers himself and realises there is no good comes of staring at your foot when you want to walk: ‘You couldn’t do anything until you did another thing first’.[16] And thus we all learn self-efficacy, the knowledge that we can do it and move on.

Wild goats in Galway.

Truly this is a is a brilliant and beautiful book. Do read it. Of course I haven’t explained, or even tried to do, the role of wild goats the novel. Would love to hear your thoughts.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Colin Barrett (2024: 33) Wild Houses London, Jonathan Cape

[2] Max Liu (2024) ‘Wild Houses by Colin Barrett, review: One of the best writers working today’ in the i newspaper (January 18, 2024 12:03 pm(Updated 6:58 pm)) available: https://inews.co.uk/culture/books/wild-houses-colin-barrett-review-2848545

[3] Ibid: 245.

[4] Ibid: 48f.

[5] Ibid: 34

[6] Ibid: 17

[7] Ibid: 6

[8] Ibid: 63

[9] Keiran Goddard (2024: 49) ‘A caper in County Mayo’ in The Guardian Saturday Supplement (13.01.2024), 49.

[10] Ibid: 172

[11] Ibid: 202

[12] Ibid: 255

[13] Ibid: 121

[14] Ibid: 131

[15] Ibid: 104 – 6

[16] Ibid: 245

2 thoughts on “Sheila says: ‘I know the sorts that do be congregating over there. That house is a wild house’. This is a blog on Colin Barrett (2024) ‘Wild Houses’.”