‘ “The point is if you’re going to do things other people don’t like, you’ve either got to put up with them not liking it, or you’ve got to hide it” … “…maybe you just don’t know … about all the things I’ve hidden, because I’ve hidden them” ‘, says Hal, the main character of this novel to his sister, Phillipa. Phillipa replies ‘ “What can you possibly still have hidden? Now that you’ve let the whole world know you’re a practising homosexual’.[1] Should the modern queer novel be still concerned about what we hide or conceal from others? This blog is a reflection on secrecy in queer novels, based on having read Alan Bratton (2024) Henry Henry London, Jonathan Cape.

Alan Bratton with his mentor, Brandon Taylor (right and left in the photograph respectively) with the USA cover of the story with (extreme right) ta detail from the novel’s UK cover.

In this blog, I do not want to really focus on my own assessment of this novel but on the perplexity it caused in me about the role of the concealed in the queer novel. Of course queer novels are always written in the context of whether queer lives are considered to contain stories others may want to share. But the forces set against such sharing are mighty. Some think they can truly only be shares amongst queer audiences, who recognise and value the experiences described. But for a long time sharing was impossible anyway. And the barriers to these stories came from censorship laws and the power of supposed ‘public opinion’ and taste (although both were often the creation of a limiting set of public media representing the voice in fact of very few). Sometimes they have been shareable but only if certain aspects of queer relationships are either omitted or so coded into the text in some way that their full potential will only be recognised in the interpretations made by a few and which can be denied as unintended or misrepresented.

Perhaps part of that story can be told in relation to the reception of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray . It anyway lays enough background to the issue, especially if linked to the fact that though E.M. Forster wrote Maurice in 1914, it was never published during his life. I take the story on the Wilde novel from Wikipedia.

In the 30 June 1890 issue of the Daily Chronicle, the book critic said that Wilde’s novel contains “one element … which will taint every young mind that comes in contact with it.” In the 5 July 1890 issue of the Scots Observer, a reviewer asked, “Why must Oscar Wilde ‘go grubbing in muck-heaps?'” The book critic of The Irish Times said, The Picture of Dorian Gray was “first published to some scandal.”[44] Such book reviews achieved for the novel a “certain notoriety for being ‘mawkish and nauseous’, ‘unclean’, ‘effeminate’ and ‘contaminating’.”[45] Such moralistic scandal arose from the novel’s homoeroticism, which offended the sensibilities (social, literary, and aesthetic) of Victorian book critics. Most of the criticism was, however, personal, attacking Wilde for being a hedonist with values that deviated from the conventionally accepted morality of Victorian Britain.

In response to such criticism, Wilde aggressively defended his novel and the sanctity of art in his correspondence with the British press. Wilde also obscured the homoeroticism of the story and expanded the personal background of the characters in the 1891 book edition.[46]

Due to controversy, retailing chain W H Smith, then Britain’s largest bookseller,[47] withdrew every copy of the July 1890 issue of Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine from its bookstalls in railway stations.[5]

At Wilde’s 1895 trials, the book was called a “perverted novel” and passages (from the magazine version) were read during cross-examination.[48] The book’s association with Wilde’s trials further hurt the book’s reputation. In the decade after Wilde’s death in 1900, the authorized edition of the novel was published by Charles Carrington, who specialized in literary erotica.

The point has always been to hide the evidence of the existence especially of queer sex or romance even when they are not shown being practised, as in Dorian Gray, and can indeed only be inferred.

Although it is not the best writing in the book, the piece I cite below from Henry Henry plays all kinds of games with this issue, even with the fact of whether though a person may declare they are queer, or homosexual they aren’t practising (in the label used at the time) the act that makes them thus labelled. The same piece of writing is used in my blog title but below quote the text more fully because it almost contingently and accidentally it deals with why this novel uses concealment in ways that illuminate why this novel makes an important contribution to the modern queer novel. Asked to make comment on the book, Bratton’s mentor in writing, Brandon Taylor says (quoted on the back cover of the novel) that Hal in the novel is ‘one of the few true characters to emerge from this generation of queer literature’. I sense that Brandon feels that because Hal’s queerness is a given – his complications and concealed life are quite other than that.

In the passage, an apparently irrelevant reference to the subject of child abuse (concerning child ‘molestation’ at school) appears innocently in a conversation. It does not link easily with other reference about which I will say more later. In the passage Phillipa, Hal’s sister, rejects with child-like candour, and some ignorance of the reality of child abuse, the realities it brings into life of trauma and confusion. In referencing it, I will start with the end of Phillipa’s speech where she is bemoaning her father’s decision to send her to a true Catholic School (the Lancasters are a Recusant family) ran by the Catholic clerisy rather than its laity:

She said, “ … I wish I’d be sent to Mount Grace. I don’t see why I wasn’t. They were letting girls in by the time I started senior school.”

“I don’t know, I suppose because Dad was less willing to take the chance that you and Blanche might get molested,”

“I would never let myself get molested. I would kill myself first.”

“Well, quite. The point is if you’re going to do things other people don’t like, you’ve either got to put up with them not liking it, or you’ve got to hide it”

“You never hide any of the bad things you do.”

“Or maybe you just don’t know,” said Hall, “about all the things I’ve hidden, because I’ve hidden them” ‘

“What can you possibly still have hidden? Now that you’ve let the whole world know you’re a practising homosexual”.

“Strictly speaking you don’t know if I’m practising …”

Phillipa’s voice sprang out of the darkness: “Are you?”[2]

It’s a difficult moment in the novel, for the reader already knows here, as Phillipa does not because it is ‘hidden’ from her and the world generally, that Hal has been, since his childhood, sexually abused by his father, Henry. The understandings between Henry and his son impinge more on the issues she raises than she will perhaps ever know for Hal will communicate the problems of male-on-male rape only in a kind of code. The reader, however, must feel with Hal, that when Phillipa says: “I would never let myself get molested. I would kill myself first.”, bound up within a great deal of incommunicable feeling in Hal, unarticulated here of course, about Hal’s own feelings of guilt about the abuse suffered from his father (and possible by his father from his own father) and his semi-reluctant participation in its continuance as a sexual relationship. That relationship is hated by Hal but it is not quite as one-sided a relationship on the father’s side as a lesser novel might dare to show it. Hal’s complicated feelings are complexly bound up in paternal affiliation and attachment but also desire, even as both participants age, change and take on other co-relationships. This is part of the ‘hidden’ content of the novel, though not long hidden from the reader.

Of course, as this passage demands we know, much in this novel concerns the details of the British Catholic aristocracy, and particularly its sexual morality. In many ways that estranges the novel from the mainstream of the modern queer novel where, apart from in Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (a queer novel at some level), aristocratic Catholic family morality is not a feature, as in this novel it very definitely is. In Henry Henry, this intersection with both the entitlement and duty bound in an aristocratic name, reputation and the moral precepts of institutional religion play a large part.

That feature of it is not even from the novel’s supposed source, 1 Henry IV , where Prince Hal is not in any significant way characterised as influenced by Catholicism (because Catholicism is a unqueried given). In the novel though the recusant nature of post-Reformation Catholicism is a necessary context in creating the moral framework of the novel. That is not so however for Harry Percy, the character based on Shakespeare’s chivalric character of the same name, though still heir to the Duchy of Northumberland like Shakespeare’s character, because his relapsed condition is fairly evident. Shakespeare call him Hotspur and Harry Percy certainly is a Hot Spur, if not in the cavalier sense, as the Elizabethan Renaissance knew it.

I think this novel is a difficult one to fully like, however, because it seems to demand a knowledge of the Shakespeare play only to mark that it has an entirely different character as its focus of drama and narrative. Its queering of the Henry IV barely matters (although in an earlier blog (use this link) I have looked at how the play can be queered even without Bratton’s innovations). What matters more is the queering of the queer story itself so that every norm gets overturned from heteronormative to homonormative to chosen family norms. There is very little in Hal’s attempt to choose a life outside social structures and norms that does not drag him back to them. This is probably the case for the Hotspur character too, although his resilience will I think allow the slide back to norms work much more smoothly than Hal’s, as Harry Percy eases his transition by leaving on a holiday his family is well equipped to pay for and he meets many lovely young men before settling as he will for an eligible debutante to bear on the family name.

Hugh Ryan writing about the book in The New York Times is probably right however in saying that, despite brilliant uses of drama and narration, the structure of the plot sometimes becomes over-demanding in its long detail and close anachronistic references between histories without obvious benefit to meaning. The use of Shakespeare can sometimes be more for the fun in it, in that we recognise with pleasure some of the names, such as Poins, the chief narcissist of Hal’s crowd. But I think that, in the large and except for the Daddy role-play with Falstaff I examine below, it is always effectively used, though it is in that scene where the comedic, thematic and technical brilliance, as I will show below, delves further into child abuse.

We get the first hint of child abuse or its variation in sexual role-play in another scene that apes 1 Henry IV. In the Shakespeare Prince Hal finds he has been summoned by his father to account for his behaviour amongst the commoners with which he mixes, including his companionship with the renegade knight Sir John Falstaff. Falstaff and he role-play the upcoming interview each respectively playing role of father and son, starting with Falstaff as the father, with a cushion on his head for a crown.

In the novel the role-play happens too but is proposed by Hal in order to spice up the way Falstaff, referred to as Jack and an aged overweight actor, plays the sexual Daddy role in a piece of rather childlike sado-masochistic sex The sex starts with Hal asking to be spanked, while Jack says Hal is ‘naughty or whatever’. Hal’s sexual feelings, gauged by his erection, beginning to fade he says to Jack: ‘… try to act a little bit. Pretend you’re my father and you’re really letting me have it’. Whilst, Jack’s acting was such that Hal got somewhere near to coming’, his sex had collapsed before doing so. Only when they exchange roles and Hal plays the role of his father blaming Hal, in highly bathetic manner, for being a poor copy of Harry Percy (Northumberland’s son), being too close to the queer Richard (obviously the substitute for Shakespeare’s Richard II usurped by Henry IV) and, to cap that, for being too much responsible for the Anglican Reformation does Hal achieve sexual satisfaction, rather viscerally described.

The whole point of this scene may be to look at the role of imaginary play in gay male sex, at least for some – never part of my repertoire – and we must think that (for we have no context yet for other meanings) when we first read it (in Chapter 2). In fact, however, it is an elaborated coded communication (one bound to fail to be understood by Jack for he too has no relevant context) about the fact that paternal punishment and gay sexual consummation have been inalienably associated to the development of Hal’s sexual life and his ability to play a male role. This deliberately failing communication of a big secret, a hidden life, is exactly what is replicated with Phillipa, in the scene already looked at above. Whilst a readerly audience in the know as we squirm under Phillipa’s naïve mistaken statements, as it were, is a fuller truth, which stems from something quite other than ‘being a homosexual’. ‘practising’ or otherwise. It is the secret he wonders if Jack gets, though we know this narcissist wouldn’t, near to being as Hal fancies that Jack might, wherein he:

… perhaps imagined Hal lying in bed on the nights he slept alone, coursing with vile blood and thinking, I wish I’d been someone else, I wish I’d been someone else’s son.[3]

That is a rich and rather cruel sentence that disturbs me. If ‘vile blood’ is the Lancaster blood flowing between father and son and linked to pederastic relationships, as Hal will later think it is, it is also the blood of one of the line, Richard of whom we only lately have it confirmed (by his ex-lover Edward Langley) that he was HIV+ at the time when there was no medication to manage it and when the state was complacent because it was felt it only killed gay men (it didn’t only kill gay men but states often act on myths).

Some critics feel that these connections are ill-crafted. Hugh Ryan in The New York Times, whom I have mentioned before, says of the role of Richard, whom we never see alive except in the stories of other family members. These people, especially the bisexual ones, which is perhaps most of the male products of Catholic public schools for boys with its heightened pride in their own male line) are never quite handled well in the narrative craft of Braddon, thinks Ryan. Speaking of Hal’s development. He says:

When he finally does experience a moment of catharsis, it’s borrowed from his cousin’s death from AIDS, and told in an anomalous monologue from an otherwise offstage character, smooshed into a late chapter.[4]

The relationship of Henry the father and Henry the son with Richard is never fully explicated but these omissions too are related to their shared ‘vile blood’ (in the male line – the rationale of aristocracy) and the continuing semi-consensual incestuous sex between father and son. No-one must know but many know half-truths. A key moment, after Hal, having dropped Jack Falstaff as a sexual partner for a full-on sexual and romantic interlude with Harry Percy – and something that feels like ‘love’. Harry is the left-wing activist heir-apparent to the Duchy of Northumberland, named Harry Percy if full after the family at Alnwick and is another Henry to complicate things. In a family row at Henry’s wedding, Harry retails back to the elder Henry that Hal was sexually abused as a boy without knowing, for Hal never told him, who the perpetrator was. We, as readers in the know, are able to feel that this event forces both Henry and Hal to face their hidden sexual being in public, whilst everyone else witnesses the event with half-truths in their mind. Hal shouts to Harry: “Shut up, Percy, just shut up, you don’t know what you’re saying”.[5] The whole event ends in brawl between the two male lovers, their relationship dissolving in the heat, and every cause of the events still secreted. Hugh Ryan is a good critic but I think his summary of the narrative treatment of abuse misses some difficulties in the novel’s prose. He says:

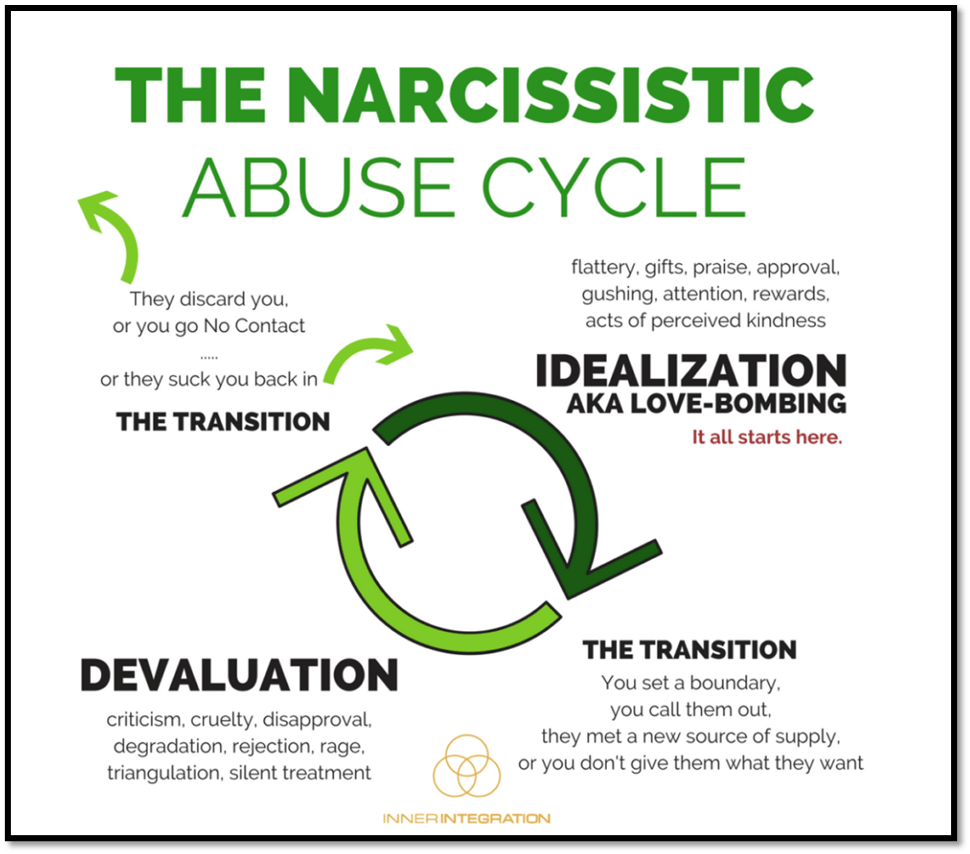

Hal reacts to others’ actions, feels guilty, lashes out and gets trashed — a cycle that repeats and repeats. The book tells us that “Hal liked to have fun, he liked not to suffer,” and that when he got punished for misbehaving, “on him, the consequences were charming,” but we are so deep in his mind that his guilt and unhappiness dim any such lighter moments.

This seeming paradox is explained a few chapters in, when it is graphically revealed that Hal is a survivor of ongoing sexual abuse that started in childhood. He bears the pain of both his betrayed child self, wondering why God let this happen to him, and his ashamed adult self, who wonders why he hasn’t spoken out about it.

In Hal, Bratton offers a psychologically acute portrait of the kind of trauma-born narcissists who yo-yo between judging everyone else as beneath them and hating themselves for those very judgments.

But I want to look deeper at what Ryan labels narcissism (oft a resource in the analysis of queer love) in Hal for it seems too convenient a label. The sex scenes between father and son made me uncomfortable but they are meant too, because they are true to the way bodily mechanisms interact with the sensuous, cognitive-associative and moral determinants of sex, though rarely in the novel of penetrative sex in the novel itself.

They register Hal’s horror effectively at moments where sex and violence morph into each other with a strange hint of pleasure mixed in. At one time Henry pushes Hal against a door, takes ‘a fistful of hair’ and knocks his son’s face into the door. But without Hal being able to see what his happening to him, we find that disturbing mix baldly stated. Henry ‘let go of his hair: his scalp was pleasantly sore’. Hal’s consciousness of the ‘pleasantly sore’ is what disturbs. If the pleasantly sore’ is concerning, so is the sound of his father ‘unbuttoning and unzipping, fabric wrinkling and shifting’, behind him. The prose captures the unseen non-penetrative rape but somehow renders it almost welcome: ‘as Henry’s breath mounted, exhalation by exhalation, into the unconscious expression of quiet, innocent noises’.[6] There is no attempt here to render the response of Hal as simply one of disgust, fear and horror, it is mixed with the sense of rhythm of the sentences into something disturbingly pleasant and innocent, whilst not being so.

Perhaps, this is the hidden in this novel. At many times when it happens Hal imagines himself as like his mother in accepting sex from his father without resisting but without active seeking iteither – though sometimes desire seems to come from Hal; itself to passively give in to the male line represented by his Father. There is force and subjection when Hal is ‘kept in place’ in the passage below but there is also a sense of mutual peace and the sensuous feel of mouth upon mouth. Is this disturbing? I hardly know what to think? It is difficult to know whether Hal invites or repels his father – the invitations seem involuntary as here:

Henry put his lips Against Hal’s and let them rest there, rather chastely, like a kiss of peace, The noise Hal made little more than a vocalised exhalation, tipped the scales weighing Henry’s desire and his fear and he put his hand in his hair to keep him in place. It was delicate at first, open-mouthed but slow, punctuated by moments of stillness.

Hal drifts into an asocial place behind a metaphorical door he passes by, where he chooses not to think of the ‘church, the law, the world, the ancestors, the family, the self, the soul’’ Is this the abused child’s trauma? Perhaps it is but it isn’t made to feel difficult or unpleasant eventually as he becomes: ‘… light and loose, unburdened, blank. He felt the pleasure of the vessel, which bears no responsibility for what has filled it’.[7]

Many passages are as difficult to gauge as this in their balance of fear and desire in Hal, as much as in Henry (indeed sometimes Hal thinks he becomes Henry). It is also balance between disgust and attraction and moral good and evil. There is a strong sense in which Bratton attempts to understand the meaning of male sexual desire by going precisely into the most fearsome place of all of our culture – the incest probation between father and son, and yet one which fascinates the culture. Why, I think sometimes, did Bratton choose 1 Henry IV though rather than Hamlet to explore the theme. In the latter the mother fascination can so easily be inverted into one about the father – two men both called Hamlet? I think it is because Bratton wanted the ubiquitous humour of the history play to dominate, for though comedy is there in Hamlet, it is mute. Another reason is because he needed the ghost of Richard II in the Henry plays, to mount another irrational force, the fear of AIDS in the early days of HIV.

The secret this novel explores then, in the end, is mainly that the body and the visceral mechanisms that guide it in the nervous system are too often ignored in the queer novel or made easy to understand in a dialectic of over-simple liberation and oppression. Shortly after the scene I have just looked at, Hal sleeps but then wakes with the sense of coming tears: ‘the same swelling impulse to cry as he sometimes did at mass’. In a play where physical reaction to stimulus (captured in the word ‘swelling’) occurs often in places the culture tells us to be inappropriate the next sentence is telling and central: ‘His body mastered itself before he had time to think whether he wanted it or not’.[8] For that occurs to men in the novel who either want or do want sex and in which mind and body sometimes pull in different directions, sometimes not. This novel faces us with situations where these two forces exist independently such that the tension between the is huge, but this is more rarely the case. I think this tells us quite a lot about the secret this weird queer novel needs to uncover in its process and progress; that the psychosocial structure of active will and passive acceptance of drives, mind and body is the last uncovered secret of the queer novel. There will, of course, be no easy answers.

With love

Steven xxxxxx ,

[1] Alan Bratton (2024: 161f.) Henry Henry London, Jonathan Cape

[2] ibid: 161f.

[3] Ibid: 13. The whole scene with Jack is from ibid: 10-13

[4] Hugh Ryan (2024) ‘A Modern Shakespeare Retelling Filled With Drugs, Sex and Trauma’ In The New York Times (May 15, 2024) Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/15/books/review/henry-henry-allen-bratton.html?auth=login-google1tap&login=google1tap

[5] Ibid: 256f.

[6] Ibid: 221. In the scene where the two men, father and son, face each other in bed, some pages earlier

[7] Ibid: 206

[8] Ibid: 207

5 thoughts on “Should the modern queer novel be still concerned about what we hide or conceal from others? This blog is a reflection on secrecy in queer novels based on having read Alan Bratton (2024) ‘Henry Henry’.”