Visiting the Discovering Degas exhibition at the Burrell Collection in Pollok County Park, Glasgow on its opening day on 24th May 2024 at 12 noon.

This blog supplements one done preparatory to my visit and before I had access to the catalogue and hence a list of te exhibited works. You can read that blog at this link if you wish. In that piece expressed a reservation probably hardly noticeable about the exhibitions subtitle: the full title of the show being Discovering Degas: Collecting in the Time of William Burrell. There is no doubt no shame in honouring the origin of a collection, although, as in the Bowes Museum in Barnard Castle, we should be wary of equating a love of art and having the wealth to display it with the meanings we offer to others who may wish to test if art is for them Hence, although the catalogue for this collection was both beautiful and full of well-researched matters about the history of art and the social history of its collection, this seems to me a matter strictly for the academic historian.

The essays are scholarly versions that address the reception of Degas, and particularly in Britain, where William Burrell (the source of the original Burrell collection) was a major factor in the appreciation, storage and gateway of access to the art. But time moves on in the history artistic reception as well as other aspects of social history. The Burrell collection is no longer only those items from Burrell but a major national collection for Scotland, and currently the UK. All of the catalogue essays are on collection. The entrance to the exhibition emphasises the timeline of Degas’s art but always in relation to its collection, a first and less important, in my unscholarly view, stage before art can be received by an audience before the extremely wealthy Yet the museums oft tie themselves to the memorial honour of founders. It will, for many be a detrimental barrier to accessing the art where the reputation of often ruthless businessmen whose interest in art were only aesthetic at a point over the bounds of being economic assets and signs of social significance and worth which can be accrued.

Hence I entered the exhibition with trepidation. Its portal being dedicated both to timelines important to Burrell as well as Degas. The walls there contained lots of business concerning the history of art collection and the connoiseurial role that I frankly find quite boring, to say the least! I don’t want to spread my gloom however, for it passed as I progressed through the exhibition and the available commentary and aids for understanding turned to the development and changes in the themes and methods of Degas as an artist, offering useful commentary and answering questions about how best to approach these topics.

Hence forgive the grumpy collage above. The only concentration on the role of connoisseur collectors, apart from the essays of the catalogue (which is again a most useful one with good reproductions of the works shown) is on a wall exhibition running along the walkway descending from the intermediate floor at which you enter the exhibition and the lower main floor where most of the best known paintings f Degas are. You can see the walkway on the left in the collage below, but I look with relief from these potted biographies of mainly rich men to the walls where Degas’s works hang, striking one first by their smaller size than one expected from your past awareness of them, ubiquitous as they are in contemporary culture.

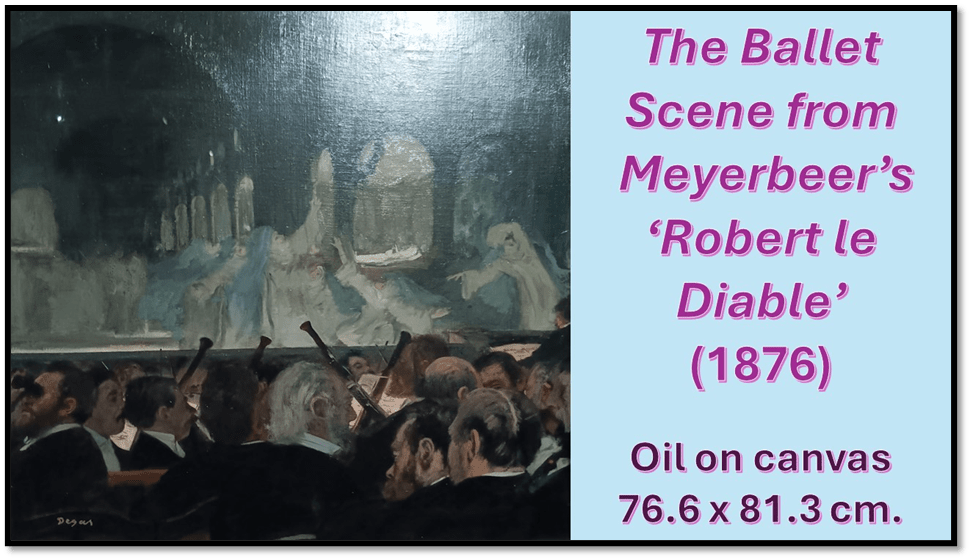

I meant to ask the question in the collage about whether curatorial matters ‘matter’, for when the curatorial focus is like this, we need to find a way of seeing the collection in alternative ways . And this exhibition obliges because nowhere, other than in the reserved areas I refer to earlier, does it actually spend most time in the retail of information on matters exclusively about the collector’s role in the production of great art. It can be safely ignored, as I ignored it, and the exhibition remain well above expectations of it. Instead we can follow the Degas timeline with interest. But if you think like me, you will have to bite your lips as you learn more about pictures that seem a kind of miraculous achievement, such as the early painting near the entrance, borrowed from the Victoria and Albert museum, The Ballet Scene from Meyerbeer’s ‘Robert le Diable’ (1876).

Why did I have to bite my tongue? It is because the genesis of this painting, of which this version is we are told ‘one of Degas’ finest masterpieces’, as described by the catalogue editors ( Pippa Stephenson-Sit, with Dr. Yupin Chung) is clearly situated as a MEANS of pleasing well-known collectors with the money to buy the paintings as well as the social savvy dealers who had feelers in that rich pool of rich collectors. The man looking through opera glasses on the left, for instance, is thought to be Albert Hecht (1842 – 89), ‘an avid collector’.[1] Well, this kind of connoiseurial knowledge base may inform but does not help me in diving into what this picture actually does to me. In my preparatory blog, I concentrated on sex/gender as a theme in the life-work in Degas, and, as I continue to try and interpret my sensations consequent on seeing the painting, I think this idea fruitful. In this picture bifurcates the picture surface between the high realism, like that of predecessors Bataille and Caillebotte, who created pictures of bourgeois male life of a high fascination, in its lower cramped register full of bourgeois gentlemen, including Hecht, if it is him, whilst in its upper register divided from the lower by the line constituting the edge of the proscenium stage, though some huge instruments held by the gentlemen of the orchestra intrude, is a scene of high feminine fantasy and make-believe. The scene from Robert le Diable depicted (‘the provocative “Ballet of the Nuns” in the third act’) was notorious in Paris, from its first presentation in 1831, and is, Wikipedia commentators believe, a major reason for the confident reception of the whole opera in France. Wikipedia also cites the reviewer for the Revue des Deux-Mondes:

A crowd of mute shades glides through the arches. All these women cast off their nuns’ costume, they shake off the cold powder of the grave; suddenly they throw themselves into the delights of their past life; they dance like bacchantes, they play like lords, they drink like sappers. What a pleasure to see these light women..[2]

The scene is the culmination of a Faust-like contract between Robert, the Duke of Normandy and Sicily, whose soul is sold for what, in the end, turns out to be the pleasure of the bodies of many women. In Act 3, his perfidy already clear, nuns rise from their grave and come the ‘light women’ referred to above – praising the pleasures of the flesh and devoted to a wild masculinity that, like the Devil, will take them. It is this wild scene of sexualised women offered to the gaze of men that Degas represents where the Gothic scene is as fantasised and blended into wild representation of the liminal sexual, where female excitation finds its own fulfilment, with other women, it will not have gone unnoticed.

The picture has a life outside those nameable male dignitaries in the lower register, who seem disengaged from the wildness they barely feel. For instance Hecht’s opera glasses are not trained on the stage (for he is in the front row of the stalls of the auditorium but above and to the left at some item of the Beaux-Mondes that has entered its box high above the stage. The orchestra may be well equipped by phallic instrumentation but it pokes up in an ungainly if highly realistically into the scene on the proscenium stage in which set, balletic dance and lighting creating an imaginative mêlé representing an art of numinous awe and terror in which clothed female bodies become unclothed and the female body is appropriated for male fantasy. Now, I think the effect here might be comic rather than serious here but it is without doubt about the mixed world of an over-refined masculine, tightly dressed-up, and the looseness of sexual imaginations in which artistic men make the idea of women live, if inside well-defined frameworks like that of the proscenium arch and the depth of a grand stage.

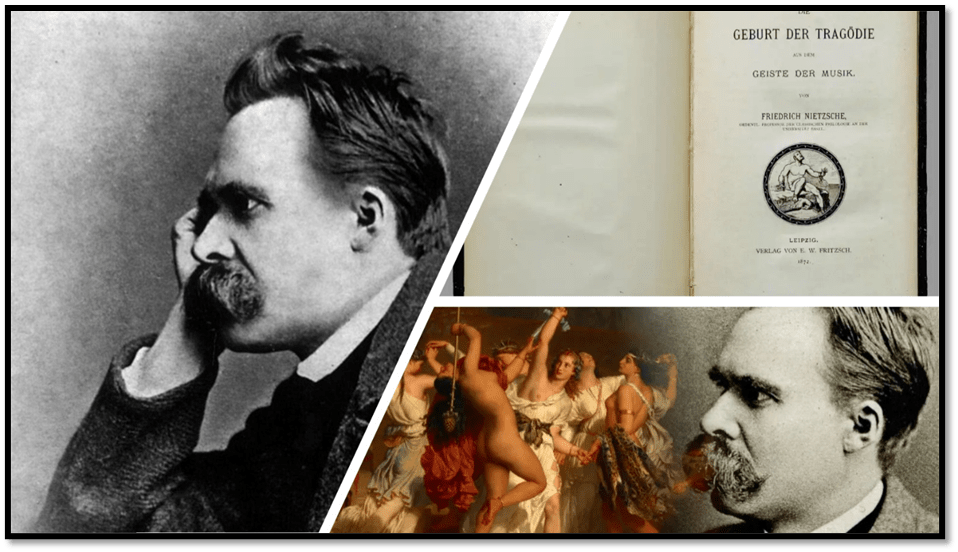

Such an idea can be frame-worked by right wing political-sexual ideologies, such as Degas believed in his public life. Daniel Halévy recorded that, in criticising Oscar Wilde and Montesquiou (famed aesthetic queers both knew), for instance, he mentions the fact that the idea of men holding a lily in their hand whilst talking to a woman was degrading because with a woman you needed two hands free.[3] The inference is that of locker-room masculinity and is misogynistic and sexist to say the least. However, it also masks the nuance in Degas’s fear that modern bourgeois men were cut off from many action (business, the army which he constantly lauded) that might make ‘real men’ of them (or him). As a painter, the one who in later life said: ‘Is an artist a man?’,[4] Degas’s identification, even at this early stage (though not fixedly) is in this world of imagined female and Dionysian creative. After all, Degas must have known that contrast of the Dionysian and Apollonian in art used by Nietzsche to characterise the duality in art of both Greek tragedy and Wagner and first published in 1872. After all, his close friend, Daniel Halévy who later wrote Degas parle…. (My Friend Degas in English) wrote in 1909 his La vie de Frédéric Nietzsche (1909). Nietzsche must have been in the air.

This idea is not to dispute Richard Kendall’s view, mentioned in my earlier blog, that Degas’s art metamorphosed constantly and particularly in his later life, even if there was some consistency in some of his chosen topics. But some themes in the earlier paintings do provide prognostics for some of these changes. A painting I did not know, and a companion study drawing which, though it is beautiful, I do not reproduce, helps us here. It is called Woman Looking Through Field Glasses (c. 1869, 32 x 18,5 cm).

As the catalogue notes tell us this ‘unnerving image’, was reproduced 8 times through his career, and is of a woman watching horsemen at the racecourse. The men appear to give the game away in early versions. The notes go on to disappoint to boast Burrel’s percipience in acquiring this work, but we go on gazing at the gazer, I think.[5] For the figure in this version is composed as if she and her background were continually playing games of hiding within each other by processes of emergence and disappearance in the eye. Degas chose his media carefully, lines in pencil drawing are breached using a wash-like medium varying from orange to ochre, but applied so that the paper background sometimes shows through, made from oil paint thinned by turpentine. It is a painting we have to gaze at carefully to determines the forms within it, including those forming an aura around the woman in the background. And in looking, we come back to the fact that our gaze is being gazed back upon, even to our detailed make-up. The observing woman observing, and carefully and closely clearly fascinated Degas and can be understood to be in line with the later independent women so absorbed in their own fascination and which becomes the absorbed self-reflection of Degas as an artist of the unconventional and queer female form, despite his public persona.

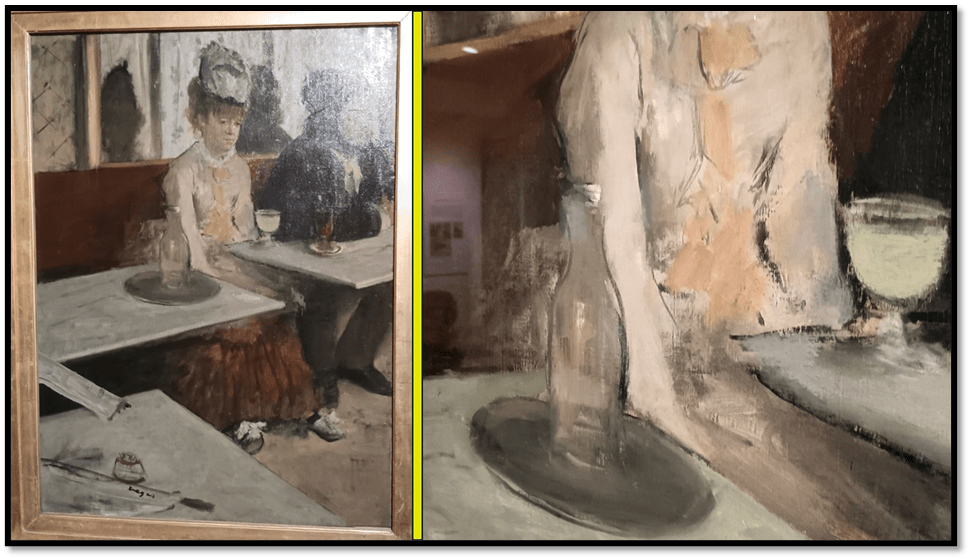

On the same intermezzine floor in the gallery we see the early great paintings that precede that latter stage with paintings of women absorbed in their independent minds and bodies. This is the great transitional object, for it transitions into an absorbed subjectivity in the painter, for the late Degas. In the early works, Degas is fascinated in marginal women – wome who do not seek attention, though these women, unlike the latter ones are bound by the codes of patriarchal capitalism. They include women deemed by society to be an underclass, whether as prostitutes, outcasts or workers in very low-paid jobs, often laundresses. In Zola, these women form a means of understanding the unseen female underbelly of Paris in L’Assommoir, published as a serial in 1876, and in book form in 1877. I think Degas is working in similar vein in the early works. In, for instance, L’Absinthe (known in English as In a Café, thus missing the central murky glass of the aniseed high-alcohol drink at the picture near-centre).

The identic of the artist occurs in the painterly manner of the use of paint, and in the capture of differing degrees of the opaque or transparent, in the shadows, for instance cast by the figures on the wall, which are opaquer than is realistic.. The painting of this abject woman challenges Degas to paint exteriors that indicate hidden interiors, perhaps the object of great painting. The flow of spirit in this picture is the flow and patchwork relationship of the overlayed oils. It is most beautiful. The catalogue attributes the scene to the influence of Baudelaire and interprets it as about, given the shifting nature of the gaze of the figures tracked by the gaze of the artist and viewer, as about ‘the uncertainty of real-life observations’. It became, the catalogue also informs us, the centre of a debate ‘between critics, artists and the general public in the press surrounding the nature and purpose of art as defined by Degas and “the new painters”, as well as the role of art critics’.[6]

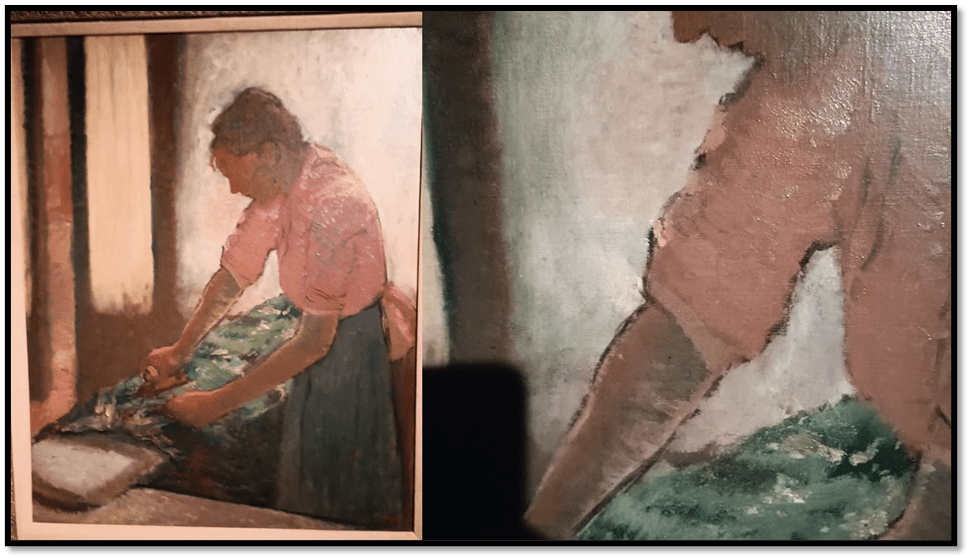

The issues resolve I would say to the uncertainties of bourgeois patriarchy about sex/gender binaries. And so in the fine pictures of laundresses, as in Woman Ironing (1892-5), which do come from a later period and use oils as if they were pastels (or perhaps gouache), at least to my view:

Nothing could be more beautiful than this painting. In this late period the laundresses do not recall those in Zola. As the editors of the catalogue say, this ‘woman is dressed modestly. She works alone and is fully absorbed in her task’. Edmond de Goncourt, they say furthermore, witnessed that in painting these late works containing laundresses, as he painted Degas was ‘talking the whole time in their technical language, and explaining smoothing irons, circular ironing’. Degas paints that is in the manner of ironing. However I reject the view that Degas did this to copy the Japanese Ukiyo-e exploring female subjects both erotic and mundane. Rather Degas wants only the viewer to be absorbed in the self-absorbed body of the figure here rejecting its possible availability as a sex-object. He has to become the woman at her task. I could look at it for a long time.

In passing perhaps we should dispose of the usual use of the Japonisme tendency in Degas, which the exhibition justifies by using an example, though this is not done in the catalogue notes though the Ukiyo-e pictures are placed near to each other, his aquatint of Mary Cassatt at the Louvre. Yet that seems a wanton search for influence. The prints of Floating World geishas, such as the one I collage below with the Cassatt portrait, is Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Wanting to Sober Up Quickly. Its comedy is deeply linked to the stereotype of the geisha community meant to raise a laugh at the use of free-flowing saki in their work. I can see little relevance to either the laundress picture above or the Cassat picture, which rather satirises Cassatt and her sister’s blue-stocking bemusement at the work of Etruscan art, a sarcophagus with the image of a ‘married man and woman forever locked in union’. This viewing is entirely a fiction invented by Degas for the original picture showed Cassatt and sister with the paintings at the Louvre rather than antiquities such as these. Again the issue questions sex/gender issues, and renders problematic the absorbed gaze of Impressionist artist fellow, Mary Cassatt.[7]

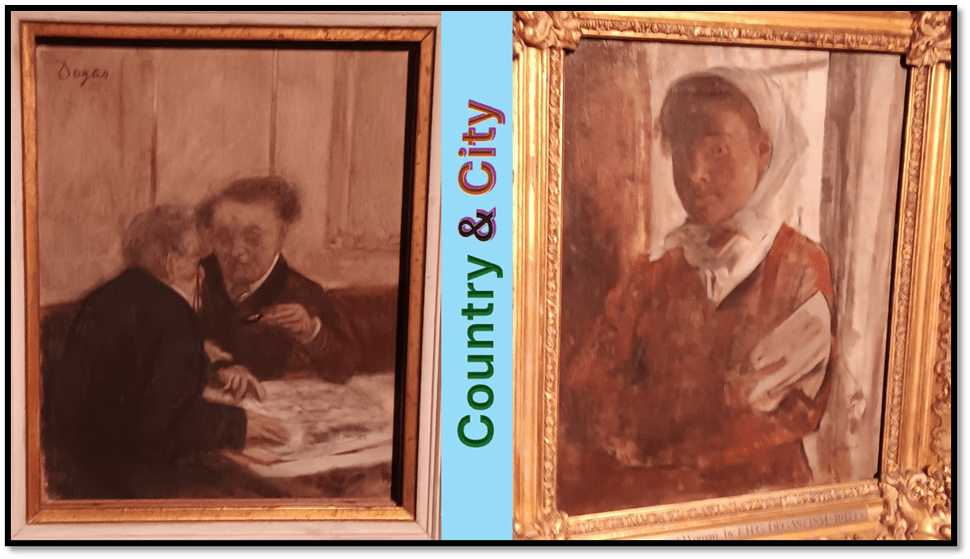

However, in the schedule of exhibition I have jumped to pictures at its end on the lower floor, bypassing all those lives of collectors, There is much beauty in the upper entry floor but I want to pick out only 2 other works that I did not previously know. They are in the collage below, respectively from left to right: At the Café de Châteaudun (1869-71), a work of urban observation, and A Peasant Woman (1871). I cannot know how I might interpret these pictures but the intrigue me. One comparison though seems clear. The catalogue imagines a narrative behind the young lower-class rural women, holding a piece of paper (they guess a letter from a lover away in the Franco-Prussian wars) and gazing in the far distance at the receipt of news that makes her sad.[8] We will never know. As far as we can go is to admire the capture of a female self-absorption that is not meant to excite erotically/.Patterns of light and shade make this a painting of mood not appearance – achieved by painterly methodologies that feel to me quite amazing. The feeling is part of cognitive-emotional depth created by paint.

In contrast the two gentlemen are sallow figures, locked into the papers they look at together, one grasping the other as in shock at something they read therein, and that one points out with a finger. The feeling of enclosed intrigue and secrecy is palpable to me, though not picked out by the catalogue editors. What they see in the ‘multiple lines and dark patches’ in the face to the right is a kind of tromp l’oeil figuration of ‘the blur of movement’.[9] To me they seem signals of a kind of duplicity, enforced on either the oppressed or chosen by the schemer. I can’t get it out of my head that these men are reading of the scandal of another man caught im scheming because he had to, a fellow queer gentleman operating in hiding. That’s fanciful of course, but no more so than the editors are – just ready to include the non-normative potentials of city life, as indeed most urban French writers did, whether Balzac or Zola,

As I now hover between floors in the exhibition, I will bring together, as I do in the collage below (titled on the collage), sculptures in vitrines on both (only the larger figure being on the top floor, and an undressed study of the famous trainee ballet-dancer of 14 years-of-age.

To see these in situ was much more enlightening for the same reason I must disappoint by representing in two dimensional photographs. One can see around these figure and you do partly because to me their wonder is in the testing of balance is complicated human postures where body and limbs are in unnatural extension or torsion (as we see in the nudes and working dancers in paint or pastel). If the classic fourteen year old has a more conventional and easily balanced contrapposto stance, the smaller figures ought to tottering on the twisted sole of one point as they dress, or examine a painful site on the sole of one foot or use their arms to hold an angle tending to a fall. It is this smaller late pieces that seem to me wonderful, for their self-absorption works at the level of the physical as well as the emotional and cognitive, and their rejection of sexual pose for the male gaze. The 14-year old is more problematic and I am unsure how to read it. If you have feedback I would be grateful.

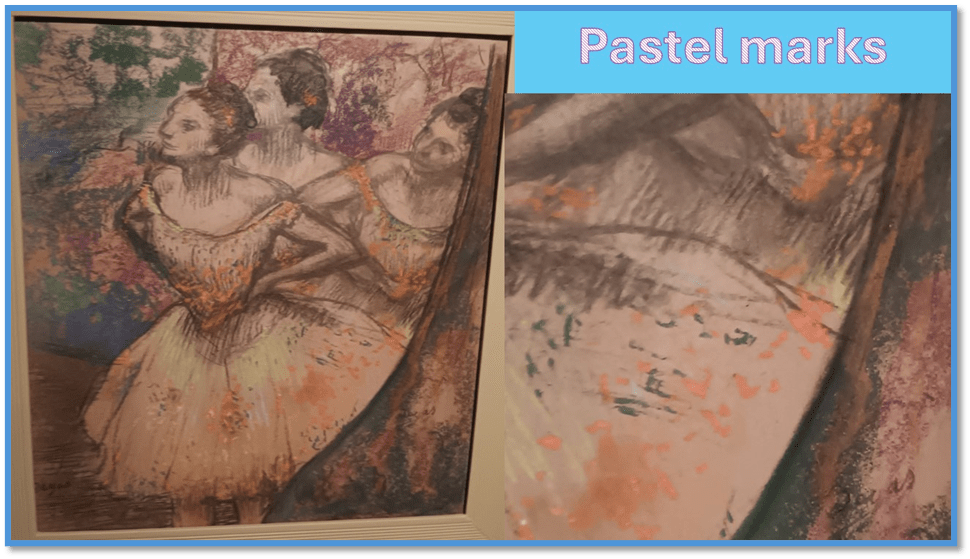

In pastel marks the absorption of the artist in the smallest of marks seems of a piece with the working ballerinas. The piece is Three Dancers (1900-5, Pastel on paper, 50.8 x 47cm). These dancers are not imagined on stage (Degas did not work directly from on-site observation though he took sketches). The catalogue tells us how Degas worked with pastel, sometimes dipped into water to create fluid effects, created by an applied ‘dab in spots and short lines’, or squiggles even as I see in the opaque and transparent effects of the orange wet pastel markings.[10] These subjects are not at work but observing the stage for their entrance. Again the effect is of absorption, readiness and flexed muscular balance caused by the torsion of watching the stage without being seen by the audience (yet!).

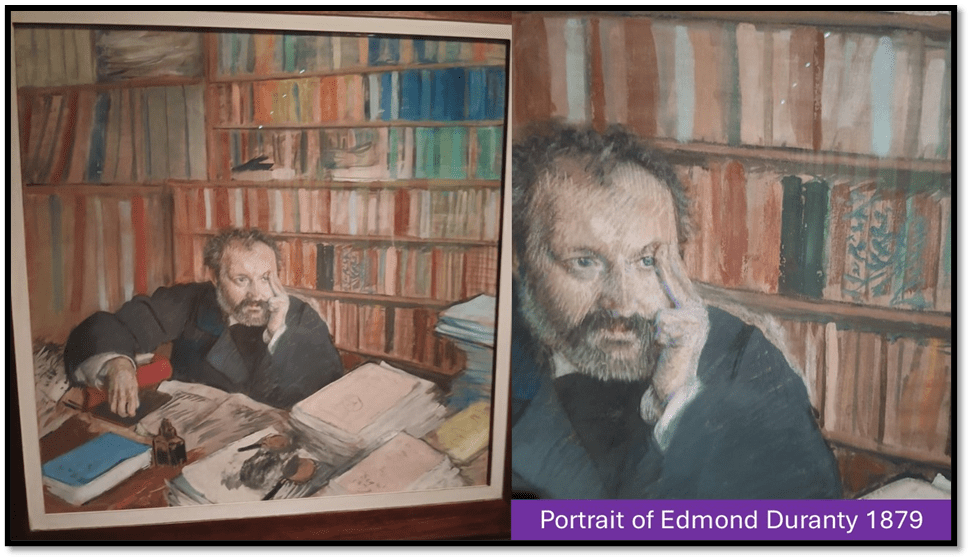

Degas’s study of men who are in some way in the arts have a similar interest in absorption. Below is the large Portrait of Edmond Duranty (1879, Gouache and pastel on linen, 100 x 100.4 cm).

A critic and novelist, Duranty referenced Degas without naming him in his book La Nouvelle Peinture of 1876. The catalogue rightly I think applies a passage from that book (in translation) to show how Degas captures the novelist in a manner that passage recommends. What they don’t say is that, in doing so, degas is also characterising himself in his fluid use of visual marks using overlaid media. What I think particular is the capture for both of what Duranty recommends for portraits of artists in modern art: ‘the study of … the particular influence of his profession on him, as reflected in the gestures he makes: the observation of all aspects of the environment in which he evolves and develops’. Of course, as the catalogue shows the interaction in Duranty of absorbed mental reflection, in a typical distant gaze perfected by Degas, with walls of books, papers and writing implements.[11] But those elements also are reflexively captive of Degas himself, who overlays books by paint and pastel dabs and stripes, fusing bookends with each other, and overmarking them in ways that cross the lines that ought to define each book. Degas’s signature (bottom left) is inscribed as if on the title page of an orange-paper-covered book Duranty is using and Duranty’s face is marked in a painterly way not unreminiscent of Van Gogh. It is a tremendous painting. I did not know that before, Likewise the painting placed next to it in the exhibition of Diego Martelli (1879, Oil on canvas).

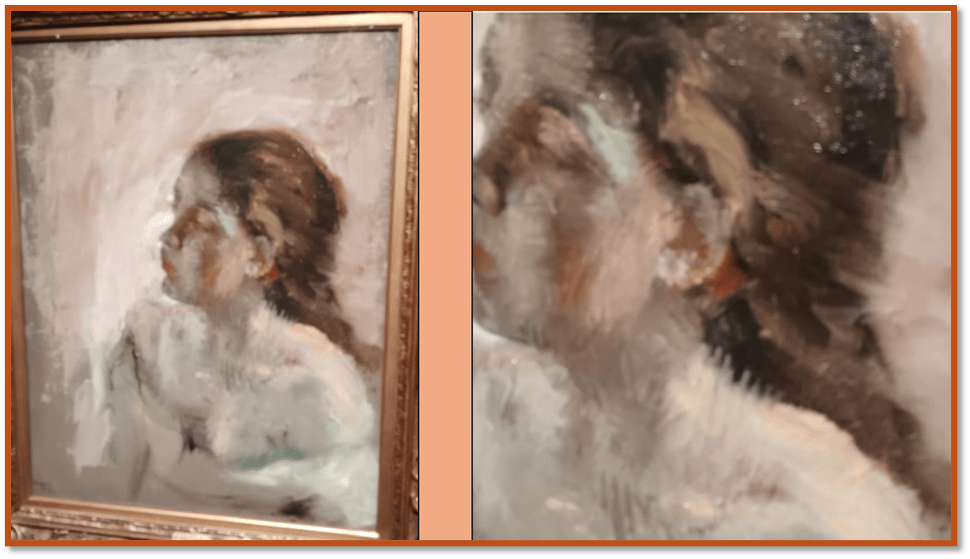

What intrigues me here I think is the imposition of the painterly upon another painter, emphasising the heightened red in the face of Martelli, by surrounding with dabs of red, that only loosely defines objects in the space around him; such as the red interior of the slippers to his left (th red refusing even to stay within the object that ought to define it but spilling over like blood, and the red fez and handkerchief (that is how the catalogue guesses what these indistinctly delineated marks represent as objects). There is need to see this again. It belongs to the Edinburgh National Collection so I may even do that. Degas’s chosen viewpoint towers over Martelli, diminishing and foreshortening him. Indeed, as the catalogue says, Martelli even noticed that, though he wanted the painting (and was not given it because of his objection to his foreshortened legs that somewhat de-masculinise him). However, before I return to paintings I at least knew of, I wanted to liner, as I did on the day on a tremendous painting of the late 1870s, Study of Girl’s Head (Oil on canvas, 57.1 x 45 cm).

No other painting I saw or knew makes the case so clearly that I made in my preparatory blog for the ways in which Degas used overlayed marks of oil to defuse the objectivity of the figure – feminise it, I claimed. And no other plays such tricks in doing so between model, foreground and background, where reflections of paint define a ragged space which, while behind the girl in our perception mainly, seem from the bottom left hand corner and along the frame edge at bottom seem to grow as a screen that is about to engulf her image below it. Likewise see how yellow brushstrokes efface the barrier between hair and dress, and perhaps the flesh of her torso. Imperceptible reds become clearer on further gazing on her cheeks, striated with other colours, lips and eyes.

Grey paint marks which may have been made by the fingers (in the catalogue they call them ‘similar to marks made by pastel’) it seems to me cross boundaries everywhere and consumes, as if with shadow but too ill-defined to be so the neck blow a blushing cheek. The catalogue also notices the use of a dry instrument (perhaps a dry paint brush they guess) to ‘incise lines into the paint surface’ of the forehead. This is excellent in helping us to see how Degas’s facture marking impels his own subjectivity into the self-absorbed object-subject of the model before him We benefit I think by not knowing who the model is. What we see, and I would say feel too, is the ‘energetic, almost frantic application of paint’ that impels us into the painting that only masks its daring under the term ‘Study’.[12]

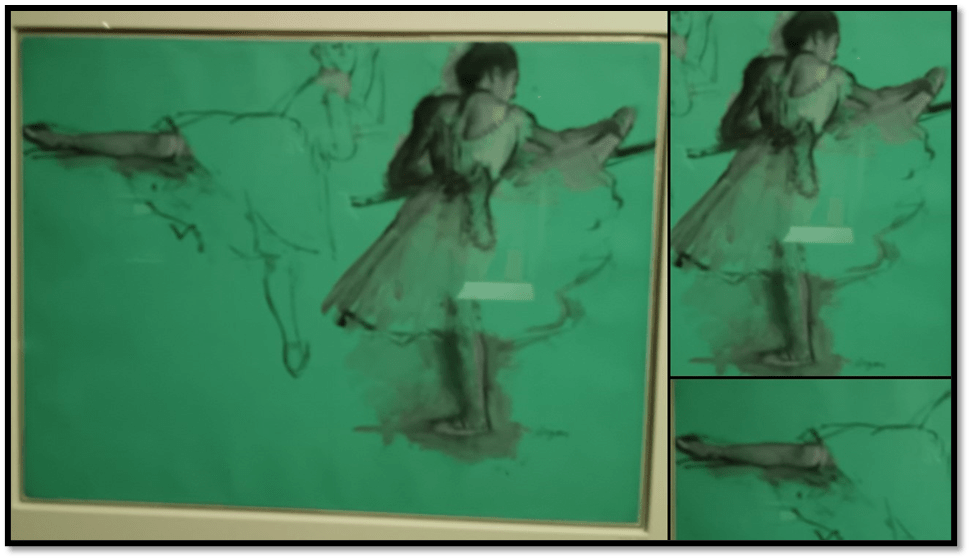

It is anyway difficult to be certain whether in Degas ‘studies’ are not complete works in themselves. I felt that looking at Dancers at the Barre (c.1876-8) which again uses oils thinned with turpentine but still boasts its completed incompleteness by using the medium to draw, as sketchy outline sometimes or with three dimensional looking tones at other points the figures of two dancers.

This picture haunted me, though I had seen it in reproduction many times before. According to the catalogue the piece is meant to boast Degas’ own innovations in drawing and painting when he worked with printmaker Michael Manzi.[13] It shows, they editors go on to say how Degas wished to show the way to manage the torsion in bodies that are in danger of imbalance from it. For this reason it minds me of the sculptures I mentioned earlier. My own interpretation here, for what that is worth and I am no expert, I think the effect achieved is of rendering the surface both opaque and transparent in relation to the dancers, allowing partial forms to emerge from wholes to stress their facture and their place not just ‘at the barre’ in ballet rehearsal, but in the mind of te artist, of whom they are projections. Because the two figures are separate studies he offers no common ground for them to stand upon – instead the float out of his head onto paper in ways that offer no embodied whole and minimise sex/gender markers, except where momentarily shows the flow of a ballet skirt at one edge, for one of these dancers.

He renders them not gazed at – for the role of the viewer is further to make them into wholes in their imagination. Whatever, the gaze is not sexualised. I think this is why we get no faces, or when we do, get a kind of stereotyped face that was often thought of as ugly, like the faces in Three Dancers above. His model Pauline used to complain that he did not represent her own good looking face. And he did this with his other stereotypical if earlier subject, male racehorse-riders. Here is his best example JockeysBefore the Race (1878-9 again using oil essence).

The face of the male jockey has the same over-round framework of face of many of the dancer studies and is relatively unspecific. The catalogue makes reference to the influence of Hiroshige on this subject and in depicting the sun through a misted barrier. There is something of a two register feel about the picture where a foregrounded pole seems to cut the picture into two. It operates even like a differentiation of two scenes though the horse’s muzzle on the right projects behind the pole into the wider left register and obscures half of the moving horse in the right register. The sky is differentiated in each register. On the right greens in the sky reflect the wave-like grass. The movement of the horses and light source on the left emphasise the rather grim only slightly compromised minor motion in the horses’ back left leg that is otherwise a picture of stasis on the right. I do not know how these horserace pictures contribute, if at all to the depiction of sex/gender except that they model the modern ‘cavalier’ which Degas sometimes sees as the model of masculinity. If anything, the painting strikes me as a picture of masculinity deeply compromised by a lack of integration and completeness.

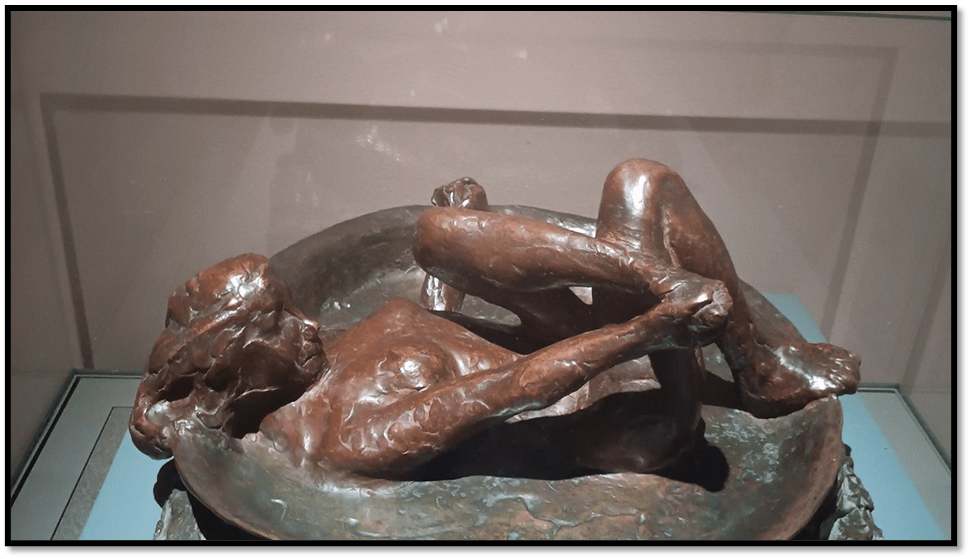

Of course the exhibition ends with many representations of the scenes of women’s toilette preparations. it was great to see the sculpture The Tub (1889, cast 1919-21), Bronze), which is the only one I have seen before in Edinburgh. The same interest in the absorbed torsion of the female body in everyday action or in work is seen here, and the same self-absorption and lack of awareness of the male (any other) gaze. Degas claimed such sculptures were merely preparatory .

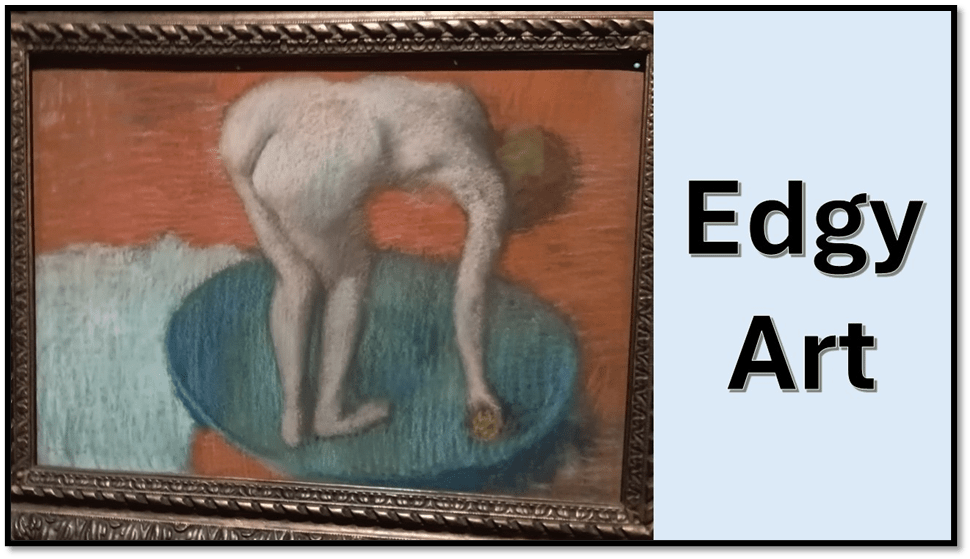

I doubt it because they are no less edgy and seemingly unfinished in conventional ways than his toilette pastels such as the edgy piece known as Woman in a Tub (1896-1901, pastel on paper, 60.8 x 84.6 cm).

I label this ‘edgy art’ in part to reference the debate I mentioned in my preparatory blog about the supposed voyeuristic quality of a nude woman caught unawares. My own feeling is that Degas is more interest in its edginess as a challenge to the representation of edges – those between objects and flesh and between masses of flesh, such as that which characterises the crack of the woman’s anus and she bends, balancing herself by squeezing her thighs together to create a more solid balance on the tub. Huysmans who was openly queer felt, as the catalogue tells us, that such details represented women and female flesh as undesirable and ugly, and was cruel to women. Degas disagreed wanting to show women ‘only concerned with their physical habits’.[14] Correct is correct, of course, for to see the body as it is and not as iconic of either self-sustaining objective beauty or of the desire of the viewer, male or female. Hence the geometric and linear structures and passages of complex nuanced colour, in flesh and objects. The colours in the body especially on the thigh facing us, reflect the blue of the tub itself. Degas is not sacrificing woman to male gaze but trying to persuade us that in what we call the ‘real world’ we rarely see women (or men come that) as they are but as some socio-cultural cognitive mode filter our perception top-down of what body form actually is. And it is a thin of asymmetrical cracks and volumes and masses of substantial flesh in our everyday actions in men as in women. However the standard Degas had to challenge at the time was the set standard of the beautiful as feminine.

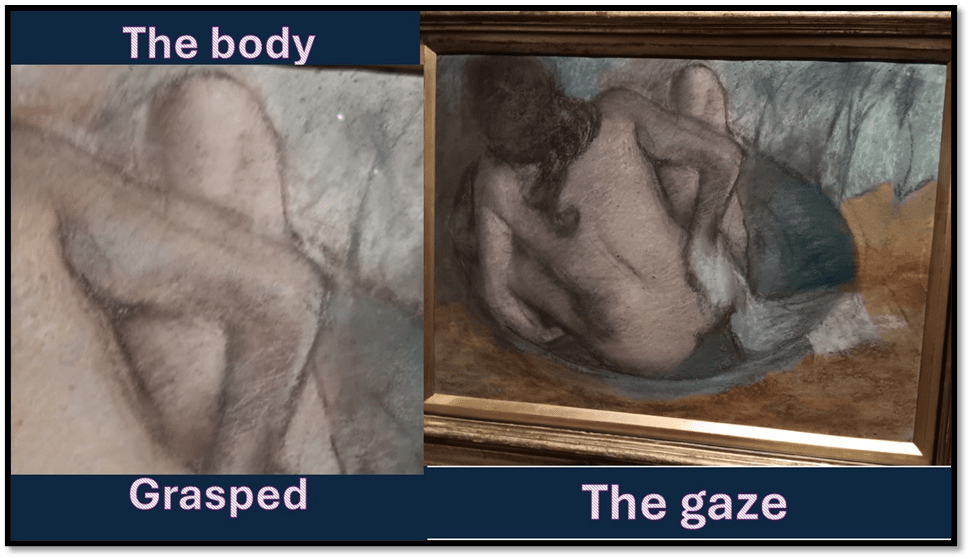

The above painting is beautiful but its beauty lies mainly in the organisation of marls, and illusions that integrated marks make, by the consummate artist with their consummate subjectivity. Cracks and conjunctions between masses of flesh are easily seen in a tub, as in the exquisite Woman in a Tub of c. 1884 below:

In order to grasp embodied form, we must grasp it in ways we might think of as ‘unposed’, by which we mean mentally unaware of its viewer, The catalogue helps us to see that but comparing this female nude to that classically painted in the Renaissance in The Birth of Venus, or Susannah and the elders’ (and could have added Diana and Actaeon) and imitated thereon. And that meant seeing flesh and its ambiguous edges as they are not as they are idealised in the mind. Some critics in 1886 said of the bodies that they were of women who ‘bear the bruises of marriage, childbirth and illnesses’. And so they should if we are to see sex/gender construction in its fuller social consequences. For Degas that was a gateway to real subjective private beauty rather than to social reforms that he as a conservative right-winger did not support. No-one ever said art was without contradiction.

Of course some of the nuanced response to some pictures can find within it some pictures that, despite the facelessness of the women, by posture or screen, does participate in voyeurism. I think the beautiful Woman Combing Her Hair (c.1887-90), which used downward falling folds and flows to guide the eye of desire. It is quite unlike later pastels., as is the 1887 pastel Woman at her Toilette, which I find intensely voyeuristic (although it fails to work on queen men like me). I don’t reproduce the latter however.

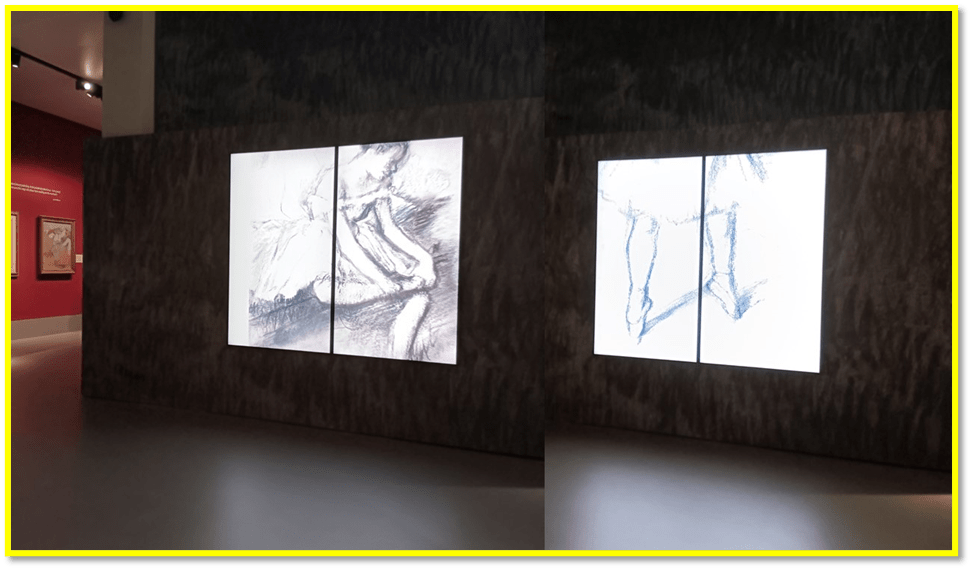

Let’s end by praising how this exhibition used animations to help us see how the layered application of pastels and the replication of forms (sometimes sequenced forms) created the characteristics of how Degas manufactured form and design effects. All in all this was a great experience.

And I have to say that the staff at the Burrell are superb – so friendly and so helpful, Do go. It is on a long time.

With love

Steven xxxx

[1] Pippa Stephenson-Sit, with Dr. Yupin Chung (2024: 40)’Catalogue of works in the exhibition’ in Culture and Sport Glasgow & Frances Fowle (ed.) Discovering Degas: Collecting in the Time of William Burrell, London & Dublin, Philip Wilson Publishers, Glasgow Life Museums & Bloomsbury Publishing. 37 – 153

[2] Cited: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_le_diable

[3] See Richard Kendall (ed.) [2000: 241] Degas by Himself: Drawings, prints, paintings, writings London Little, Brown and Company (UK).

[4] Ibid: 316

[5] Pippa Stephenson-Sit, with Dr. Yupin Chung, op.cit: 53

[6] Ibid: 50

[7] Ibid: 152

[8] Ibid: 62

[9] Ibid: 58

[10] Ibid: 94

[11] Cited ibid: 70

[12] Ibid: 84

[13] Ibid: 100

[14] Ibid: 134