There is no way that you can read through a memoir like Slum Boy: A Portrait by following one unbending line of narrative that you expect to unfold in one direction only, for lives full of deep ruptures in personal experience, and maybe all lives, don’t work that way. How do we reconcile that with the memoir of a lucky queer boy. Reading Juano Diaz (2024) Slum Boy: A Portrait London, Brazen / Octopus Publishing Group

No memoir could be more clearly written than is Slum Boy: A Portrait. Anyone who reads fictional OR factual autobiography at all will read it with joy and understanding. But this does not mean it does not have its complications as a narrative, some of which are structured deeply into its pattern of self-reference and feeling about family: those complications form part of its beauty. Half of my collage above however is from the prior printing (in Attitude, the queer magazine) of the astounding chapter from Slum Boy, which is about a boy (who knows himself as John at this point of his story) engaging in his first queer non-pretending or subliminal one-sided relationship. Nevertheless, the book as a whole is not a story of queer coming of age or is only partially so. Growing up queer, that is, is only one of the intersections of the life that unfolds so richly in the book, with the contradictions in the boy, if not the man Juano, often unresolved and still fragmented. I still find the apparent forgiveness that Diaz offers the adoptive Dad, the truest Dad of the many in the story hard to stomach. After all, this Dad effectively evicts Juano from the family home merely because he called the boy McCaw his boyfriend.

The boys kissing in the collage above is an artwork by Diaz recreating a scenario in the novel when John, well before he is Juano, kisses his friend, Mario, the trainee firefighter. The painting is called Mario’s Surprise. Kissing a man, though, is an idea richly embedded in the memoir. The kiss with Mario happens as both John and Mario learn that parents are not always open to the idea of having a queer son. Mario’s father forbids John the house because, as John recounts it from Mario’s original account to him, ‘everyone in my village knows I’m gay except my parents’. They seek sanctuary in an abandoned steel factory closed during the Thatcher era and amid ‘rusting machinery’ find signs of the ‘resilience of the natural world’. Their paradise is a fragile, uncomfortable one externally: ‘The freezing wet air is punctuated by the sound of distant cattle mooing; we kiss deeply to their chorus’. Their kissing is an exploration of the warmth of contact that lives for them as an escape from how it is to grow up in ‘a tight-knit family full of macho barriers and strong family pride’.[1]

It is a world where desire peeps out from hiding in ways of which we never quite know the young boy to be conscious. For instance, Father Andrew, a Veronese man sent to a much colder Scotland in his youth but now an old man, ‘grips my face in his bony hands and plants a gentle but lingering kiss on my cheek’ . There is a question as to the source of that closer than expected description of the kiss. Both his new brother, the first adopted son of his adoptive new parents, Jack, and he squirm ‘from the kiss’, but the rejection of what is given as a fatherly kiss is full of other potential that remains unexplored flitting between a queer boy’s moments of developing consciousness of fathers, men and sex. For instance, a page later he tells of his new mother’s disgust at him as she observes that he has ‘dry-humped a friend as a joke’.[2] There is little more to this than experimental play even when later, the now Juano, escapes a gay party to ‘hide from everyone’, at his new acquaintance McCaw’s request under a bed and: ‘Through the dark cramped space, I feel his arm move over me, and we kiss’.[3]

Other self-discoveries occur in ‘cramped spaces’. When Juano experiences male violence aimed at him and his mother in the Drumchapel slums and later in male-on-male relational spaces, it is each time like a birth again from a womb. The desperate drunken purchase of boys by the old man Freddie in his house near the Byres Road where Juano is taken in when homeless, and the turning of the same house by the criminal drug-dealer, Craig into an exploitative male brothel are both witnessed by Juano in a ‘small, confined space’, the cupboard in which he is forced to sleep, which to him is ‘like a womb’.[4]

If places can take on the role of a mother’s body (a womb) as above, the roles of the family too can be distributed widely, from suspected biological origin to origin by choice, convention or misfortune. The role of priests as spiritual fathers is part of these role distributions such as Father Andrew, whom we have already met, whose interest in John is hard to fully read. The minister of St Mary’s Cathedral on the Great Western Road is no conduit to a fatherly God who will feed him either as his adoptive mother (called simply ‘Mum’ here) promised him would be the case. A man living on the street outside it confirms to him, once refused by the minister, that ‘you’ll no find God in there’ and tells him: “Go hame, lad, if you huv a hame ti go to’.

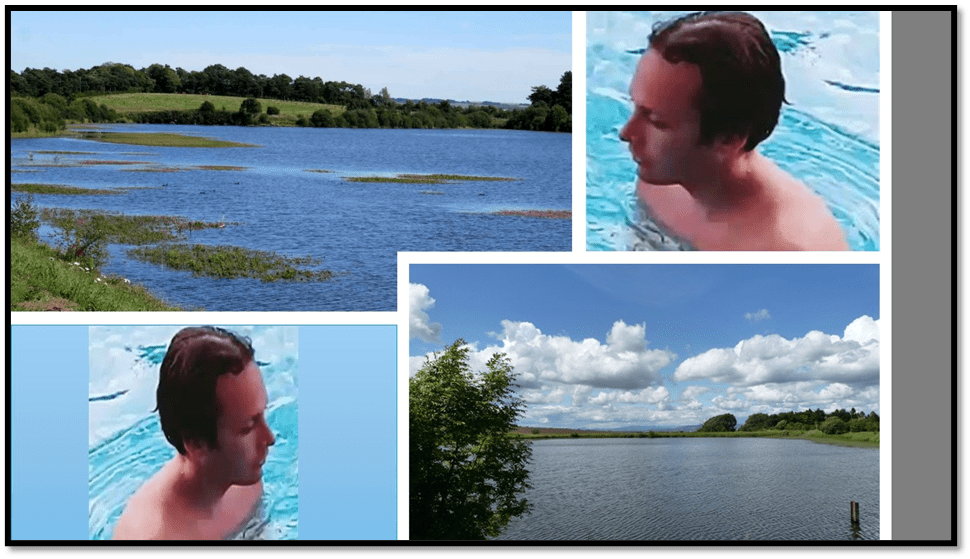

The knowledge of who is ‘hame’, whether one has one or not, and whomever are its members becomes wildly problematic. When the book opens John McKelvie (Ronnie being the drunk man, if a nice one, his mother lives with at the time is the giver of that fictitious surname) is waiting for ‘Daddy Ronnie, scanning the light that shivers on the surface, the grey sky reflected back’, as Ronnie swims in Barrhead Dam. .[5]

This is the first scene in the book as John scans the scene for a Daddy, of a kind, to emerge, but it is like much else in the book where such waiting occurs in contexts where what we appear to see is mediated by screens and barriers that hide things, even the truth of whom is a family member. Ronnie appears back at the lake’s shore but then pushes off again, only a little later [within a page of writing]. John’s vision is filled in a flash not by the reappearance of a returned potential Daddy but a new disappearance of the same candidate: ‘Ripples pulse towards me on the grass from his movement until I lose every trace of him’. (My italics). There is something ominous about the wording of this loss that will be repeated through every other appearance, disappearance and reappearance of parental figures in the novel. The language used here however is not only about the emotions of loss and recovery but about the nature of the bond in families and how that feels to each family member but especially to a boy learning about the socio-sexual behaviours of his adult carers.

The very moment that John learns his love for Daddy Ronnie is also the moment that he senses the evidence that he is attracted to the bodies of men. This is not an attraction of Ronnie’s making, though we cannot say exactly the same for Father Andrew. The beauty of Ronnie speaks to at least some of the identities of the growing Juano, if not (and how are to know) the infant John. Certainly, there is something sexualised in the holding of his crisp packet ‘like a trophy’. For this bag is ‘full of murky water and tadpoles’, reminiscent of male sexual inseminated excitement contained in a moment of excitement he can’t yet know.

Whose consciousness of Ronnie’s body for instance, do we have here?

Look at this, he says, thrusting his strong body through the water on his back, still facing me, his eyes looking deep into mine, as he floats for a second, suspended in the murky expanse.

The thrusting, gazing and floating richly illuminate the ‘murky’ waters of familial desire we have to peek through here, coming up with no answers but with a sense nevertheless that no simple label can be given to the expressed love of child to man. That is so even in an earlier sentence where John/Juano records how Ronnie’s ‘blond hair glistens, and ribbons of water rush down his shoulders’. Whose gaze follows that water down the naked torso?[6] As I said in an earlier blog (use the link to read it), though I here build on the statement below with the new words in italics:

We owe it to more than the primacy effect of memory recall that not every trace of Daddy Ronnie is gone forever. Indeed as he dies young John learns how beautiful men can be in his own eyes, and the memory of Ronnie (often too drunk to substitute for the care of John’s mother, though he shares their family life) is redeemed, washed clean and blessed in what he contributes to the boy: a sense of the beauty in loving men, however transient those men might be.

Ronnie is not the only disappearing Dad in this memoir. Juano’s biological father, we learn by the end from his elder biologically related sister, Hannah, was Jagsy, who attacked John’s mother ‘with a hammer’ and sexually abused his sisters, stopping short at doing the same to John because the latter was his biological son, ‘his golden boy’. His mother ‘took knife wounds trying to protect’ her children Hannah also tells him.[7] John alone in his flat whilst his mother his mother seeks alcohol, is asked to play the Daddy in role-play by the ‘little girl’ next door knows that this enactment is meant to be of a ‘scene of domestic bliss’, such as that ideologically supported on TV.

He says he is ‘not sure how to play’: I don’t want to be the daddy! I want to be the baby, I want to be nursed and rocked, cuddled and loved’. The ‘little girl’ next door in the tenements with her stable working class life however ‘has the entire game mapped out for us’.[8] It is the perfect image of heteronormativity. The many substitute versions of Daddy his Mum returns with, when she does return, only excel in ‘hurting my mummy, stabbing her front bum fast with his willy’. The whole notion of ‘pretend families ‘ in Section 28 is in the above turned on its head.

In contrast, his adoptive Dad ‘is a patient man, and his love for us is tangible’. That Dad, however, rather insists that he must be the only Dad that matters: “I am your dad and I love you. You have to put the past in the past, son’. [9] And this Dad is keen on reproducing in John the macho pride of his Romany family. Letting this Dad down brings the gibe that runs through the work – that he is considered the worst a boy can be: a girl: ‘“I’m getting you a fucking doll and a pram for Christmas” he’ {DAD} ‘shouts’.[10]. This new ‘forever family’ is moreover often violent too, if less viscerally so than in previous experience. His new Dad, however loving, even actively supports that code of gendered behaviour. Indeed this very Dad, in effect, gives an ultimatum to Juano that he must leave the family if he will not renounce an acknowledged queer identity. He does not bend to respond even to Juano’s later contacts, until, at least, he and the general homophobia in society have both mellowed. Moreover, it seems that Juano allows his Dad to rather soften the account of his role as a hard Dad, when they are at last reconciled. I think this is because Juano needs to believe in the necessity of family. It is why the author reproduces in real life, I would guess, a chosen family of his own.

Social work and child education, as described in the memoir, also uphold contradictory views of the family and its function too but, in doing so, perhaps also contribute to the useful idea that families roles need not be played by members biologically related to each other but can be also reimagined through self-selection as chosen families, although importantly it is the not the child who does the choosing, however paramount the wishes of the child in law. Social work even has a language to support its variance over these issues, which John learns – like ‘birth family’ and ‘forever family’. Forever roles are contradictory however. ‘Forever Dad’ Macdonald, whilst he is comfortable in wiping away his adopted childrens’ past, does not make unconditional guarantees (keeping, for instance, the condition that a boy must be and act like a heteronormative boy) of being there for those children, whatever may occur short of his own death.

Father and mother substitutes proliferate even in ‘forever’ families. John’s adoptive mother’s own father has to become Papa Bill to John too. Papa often shares the care of John because he comes every day to the home of John’s ‘forever family’. It is not unlike how John informally adopts Sister Pauline, the nun, as a mother in his childrens home (see how the family terminology gets confused in the last sentence alone between sister and mother). This confusion of roles in families in the book is often emphasised through fast shifts of narrative focus. Whilst in group care John continually waits for his mummy to arrive, although his ‘memory of Mummy is ‘defragmenting’. This is a troubling moment – for while memories of mummy by necessity ‘fragment’ (to the point, in Sister Pauline’s words, that, ‘The wee lad doesn’t know whether he is coming or going’) John’s strength seems to lie in the pulling of fragments together in the cognitive-emotional construction of a Mummy or Daddy image. What else might defragment’ mean? It fires the beginnings of his art:

Over and over I draw pictures of Mummy, a small thin stick lady, with long red hair and long eyelashes. I also draw Sister Pauline, who has now become familiar. My spiritual mother. The more time I spend in her company the more I need her.[11]

Defragmentation is an aspect here even of narrative, as the proximity of a ‘thin’ image of Mummy passes into that of a richer fuller ‘spiritual Mummy’ and a bond established in and further deepening need for mothering. The word ‘familiar’ strains back to its origins in ‘family’, with a hint of the supernatural or magical associations it also has. Sister Pauline’s home, a ‘charity villa owned by the Daughters of Charity’ indeed is soon to be transformed by a magical prose possibly miming the boy’s consciousness and apprehension of size, such that it is ‘like a fairy-tale castle, Its huge strong pillars stand strong to welcome me into its doorway’.[12]

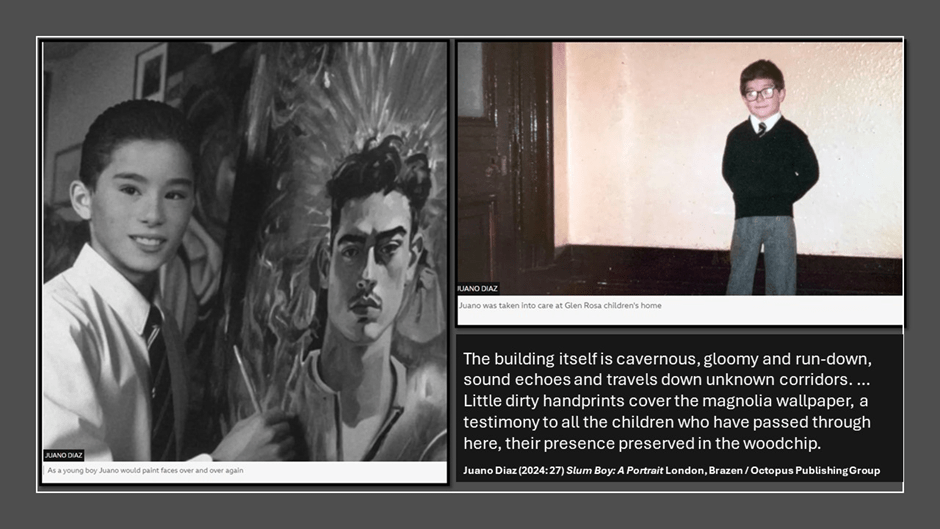

So much of this effect of the huge, strong and protective nature of the estranged familial must recapture the real memories of Juano thinking himself back into the size and vulnerability of John, for we see it in the collaged pictures below which respectively show the teenage John drawing now quite sophisticated ‘faces’, perhaps an idealised and beautiful Daddy figure, that ‘defragment’ his memories and support his growing control over sensed vulnerability. The aim of this imagery is to keep him ‘safe’. The younger bespectacled boy is reduced by his circumstances and stunted growth together. These circumstances, when he revisits them as adults, as he speaks about in the later BBC interview on the book already referenced, seem much smaller and less overwhelming than they were to the ‘wee lad’.

John’s imagination of the familial, as either gloomily unknown (see the quotation in the collage above) or huge and protectively safe, contrast with other cramped spaces of protection sought by the boy and already discussed above. This imaginary construction of walls of defence is a psychological mechanism that transforms the ‘forever family’ home of the MacDonald’s quite soon into safe space as he adopts a new Mum, Dad, and brother, Jack. To show how quickly John adopts and adapts his circumstances we see him inventing a network of temporal and spatial relationships that is ‘hame’ from the vantage point of a communal swing built by his ‘Dad’ in his new garden.

As he swings he seems like the record of rhythmic and measured time and space of music itself, like ‘the hand of Sister Pauline’s metronome’ (that metronome is a strong symbol of the novel ‘stability and reassurance’).[13] From on high, he is able to command the worlds across which his new family make ‘transit’, Dad in a ‘transit van’, a name of some import, and Papa Bill guarding the rear:

To my left is our big house, it is as long as four double-decker buses back-to-back; in front are Dad’s transit vans and our family caravan, then mum’s Mercedes car parked on the drive in the front of our garage. Behind is Papa’s greenhouse; he’s in there reading the papers. Up here as I swing, I can absorb the world around me, think, remember and dream.[14]

What is described is precisely that relation of defragmenting; taking in the world and, through mental processes at different levels of consciousness, pulling it together and rebuilding it as artistic projection. It is a beautiful moment of truth about how vulnerability is metamorphosed – sometimes. It leads him into the meaning he sought in ‘family’ and ‘familiar’ things such that he can ‘feel part of something strong and safe’.[15] It is a safety he revisits when he contrasts it to his attempt in adult vision to sum up a Birth Mother, to whom he has returned in teenage, who ‘just fucks off out and leaves (a child) to fend for themselves for days at a time’. Was it ‘her mental illness or is she just a selfish bitch’.[16]

But even good parents like to exercise power in unfair ways, sometimes with gross injustice when they fail to control their jealousy, anger and feelings of themselves being unappreciated. Mum Macdonald can become an immediate and frightening apparition of motherhood as well as an ideal Mum: ‘LOOK AT WHAT WE HAVE DONE FOR YOU! rings in my head…. I am trapped in my mind’.[17]

The dream parts of the familial defragmentation process don’t last moreover even if they are necessary. John, of course. enjoys taking on the role of ‘son’ by being named it.[18] Men are no longer just the man who, whether his mum is dead or asleep, ‘doesn’t stop fucking’ her. They are the stuff and, in the end, sole necessary qualification of biological fathers.[19] Safe in the MacDonald home, he finds a book on heterosexual reproduction that recalls a memory of ‘seeing men do that to Birth mummy and it didn’t feel right’. As he thinks that, he also imagines a faceless woman with red hair, as his Birth Mummy had red hair, who haunts his waking dreams. Again it causes him to sketch to ‘understand the woman who haunts me’ as a means by which he ‘can control the world’, and perhaps begin to see it in relation to his real, but yet still invented, family. In a shift in the narrative focus, a real voice is heard by John: ‘That’s beautiful , son, Mum says’.[20] Mothers of either many faces or faceless flit into the conscious world and a red-haired woman called Norma, an at teacher, is later mistaken for her.[21]

The processes of fragmentation and defragmentation haunt the everyday anyway – all social workers who know anything at all (and that’s not all of them) know that. The MacDonald family is one but is yet divided on itself for both better and worse. It compromises an extended paternal Romany family, in which, though he ‘don’t remember ever having a granda!’’ he gets one, actually two if you discount Papa Bill’s paternal name. As well he gets a loquacious magical fortune-telling Grandma to replace Granny Gormley, with a past into which his adopted brother Jack too tries to project himself.[22] But the family also contains a ‘gorja’ (non-Romany) sub-family (his Romany family gifts him with their language of Cant) which is Catholic, speaks the ‘Queen’s English’ and lashes out at ‘dirty talk’ and makes you wish to conform to its regulations.[23] In the background of his imagination is also a French family, if only because the MacDonalds, surprisingly for the Romany connection perhaps, don’t know Spanish names and a Spanish family, later known to be in part South African also.

These phantasy (let’s use the Kleinian spelling for it seems appropriate) familial relations play games with real instances and experiences of familial alienation, of being shut in, or worse shut out, being left at home or away from ‘hame’, or being forced to leave ‘hame’. All this includes too experience of being within a group either shut in without escape or shut out without true access, and of the felt ambivalence of Mums and Dads and their various means and ways of appearing, disappearing and reappearing. Institutions and people both sometimes refuse to confront reality, such that ‘the words’ that John shouts at on a beach, whilst with the MacDonalds, phrases like ‘Children’s home’ that are made ‘sound like dirty gossip’. Teachers can deny the experience of marginalised children and their home language usage, even the thought of mums who who ‘drink beer’.[24] Phantasy is important especially in the psychical returns of Birth Mummy to John either as the faceless woman, bitch or the vulnerable protector unacknowledged.[25]

Juano with Grace Jones, now a close friend

The ‘invented’ family (and which family is not in one way or another) of course is a theme closely tied, as I have suggested to the issue of the emergence of identity, its loss or disappearance, reappearance or reconfiguration. All of these processes haunt John, even if in the many names he has: John Mckelvie, John Gormley, ‘FUUUCK’ (his ‘name’ shouted to a policeman), a temporary namelessness, ‘Curly Tops’, Juan (mistaken for French Jean), Juan Gonzalez Diaz Abara (sounding like Joanne to him) the Spanish Juan, and ‘Pearl’ as he called by a Romany uncle who thinks him too feminine.[26] ‘WE always called you John’ his sister by another biological father, Hannah, says to him at last.[27] However there is also a meta-analysis of these names by the man Hamish, of whom Juano becomes the paid carer [an educated man], who compares John’s long Spanish name to that of Picasso in full. Of course he chooses to shorten the full name on his birth certificate, missing out the ‘Abara’ and becoming Juano Diaz. Self-invention becomes a means of standing up against inadequacies in invented familial names:

I’ve shortened this to Juano Diaz. Considering I’ve always been searching for my identity and never truly fitted in with either side of family life, I feel its legitimate.[28]

Legitimacy, even in relation to legal names, is however a defragmenting war with memory for in the best moments and in rest, Juano is comfortably all of his identities and at peace with all of them. He is constantly adding them to an ‘archive of memories’, that even includes the children’s home on revisiting it wherein there is ‘a sense of comfort in being back’.[29] It is a theme which shifts interactively with the many languages, in part or whole, which Juano learns including socially different variations of Scottish, Scottish Romany Cant, and the language of official social work.[30]

I started this blog by saying that it is not only a novel of coming out. Nevertheless, I think this must, and will for me, be part of its beauty, even though ’emergence’ rather than ‘coming out’ seems a better word for John/ Juano’s appreciation of queerness. The genderqueer themes are especially important for they segue into issues about the identity of different daddies and mummies. The story of Mario is itself interesting for his identity as queer is uncertain whilst his necessary identification with masculinity is apparently unshakeable. John knows Mario’s difficulties in loving him as ‘another’ man. They stem from ‘embracing manhood’ in a way that ‘comes with the realisation of the dangers a friendship like ours poses’.[31] Meanwhile Juano’s art, as he explores it with Norma, who has red hair like his mother, is a ‘portrait that may or may not be of his birth mother, or Norma, or a self-portrait: ‘a painting I have done, a portrait that I’ve been working on for weeks. A woman’s face. My face, feminised’.[32]

In the children’s home he exploits his smaller size to enter the girl’s room. The girls apply feminine dress-up and make-up on him. Later, at the MacDonalds’, he rejects Jack’s Action Man toy to run into new sister, Deborah’s room, finding it ‘a good space, a safe space, a visual room of colour and softness’.[33] Likewise he at first dislikes male sports, especially the ‘hard’ and ‘violent’ body orientated ones, though he likes the muscular effect of body training as his queerness bifurcates from binaries.[34] He wears make-up without his parents thinking it gay though they assert it as ‘stupid’. His Romany Uncle Tam however calls him ‘Pearl’ with clear understanding[35]. To his new parents, it is all merely an ‘outward display’, perhaps a rebellion, but it is unclear how John at this point differentiates outward display and inner identity:

My outward displays of femininity are a real concern for my parents, so at age fourteen, on any breaks from school, I’m sent to work in Dad’s scrap yard. It will make a man of me, I’m told.[36]

In the children’s home, he prefers little boys like himself to bigger ones : ones who show him empathy like Patrick and he avoids the very strange Scary Man, whose behaviours seem those of repressed paedophilia as he commands John to strip and unguard his genitals, then shutting him into another cramped space. [37] It’s a nuanced issue and certainly not a binary one as he grows. Male traits both frighten him and make him feel secure – the true definition of fatherhood in our culture.

Big strong hands are placed on my tiny shoulders by these new cousins, giving a light squeeze at my skeleton as they pass: solidarity and encouragement for keeping up the pace with the men while we ran. I feel part of something strong and safe.[38]

The binaries that get transgressed here are often transgressed in queer male development: they’re those between what is soft and what is hard, or tiny or big, which are only sometimes equated, although by the heteronormative culture, with feminine and masculine traits. Of course we have seen the softness of sister Deborah’s room preferred to brother Jack’s Action Man. But softness and hardness come together in the protection of the Macdonald home where he feels ‘buttered into these thick quiet walls’ and can ‘allow my body to become soft’ rather than rigid in fear.[39]

His Romany Aunt Jeanie with uncombed hair and a near moustache combines hard and soft in her being.[40] Although men effect to talk with each other so that the ‘conversation … shifts the subject and becomes hard’, they at other times soften into empathetic humour.[41] They treat dogs in ways they think of as hard whilst John learns to give the toughest guard-dog softness of treatment. When Mario goes for his ‘firefighting’ training he returns with ‘enormous frame’ and bulging muscles, presumably ‘hard’ and certainly with a ‘heaviness in his demeanour’. Yet his emotions still softly dance like smoke, until at least he fears public exposure as queer and, panics and leaves.[42]

There are even direct queer scenes as the novel progresses. As his life defragments, or appears to do so, in art classes he learns ‘a different kind of life’, visiting the Sadie Frost’s ‘gay bar’ under Queen Street Station (I looked when I was in Glasgow a few days ago but couldn’t find it). He finds a ‘dizzying array of other gay individuals living their lives without restraint’, lives nevertheless that constitute a group of ‘normal folk enjoying the simple pleasures of existence’.[43] Normality is not however always the aim for him, because it is a norm in which toxic violent masculinity, in the brutal pimp character Craig for instance, still plays a part – a large and heavy one that does not differ from his experience of males in his family who prove themselves by ‘beating poofs up outside clubs’.

McCaw, whom Dad finds Juano in bed with having sex, becomes as hard and as angry as his Dad is in this stressful moment. It is McCaw that projects Juano into homelessness after a trial of staying together. Some aspects of the queer scene he meets with his friend Jamie merely ape heteronormativity of a kind that disturbs, as in Jamie’s druggy wedding with the old and vulnerable Freddie who prefers picking boys up in the park at night.[44]. When Dad MacDonald softens, because ‘times have changed’ and admits Juano back into his company he has a way of blaming John for the bad experiences in his life after he was evicted by Dad from their home. I felt all kinds of ambivalence as Juano has his ‘apology’ (for what?) accepted by Dad and is told by Dad to not ‘give yourself a bad time’.[45] That Juano accepts this wordlessly tells much about the nuance of this novel – its acceptance that sometimes we must forgive where forgiveness is not earned if we want to maintain the fiction of family, for fiction is not necessarily a ‘lie’.

James Guthrie (bottom right). Dippy the dinosaur comes to Scotland. BBC News (22 January 2019). PIcture credit: . By dave souza – Own work – information from Retrieved on 3 February 2019., CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=76316756 And an external view of Museum. Picture credit: By Herbert Frank from Wien (Vienna), AT – Glasgow, Kelvingrove Gallery, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70253489

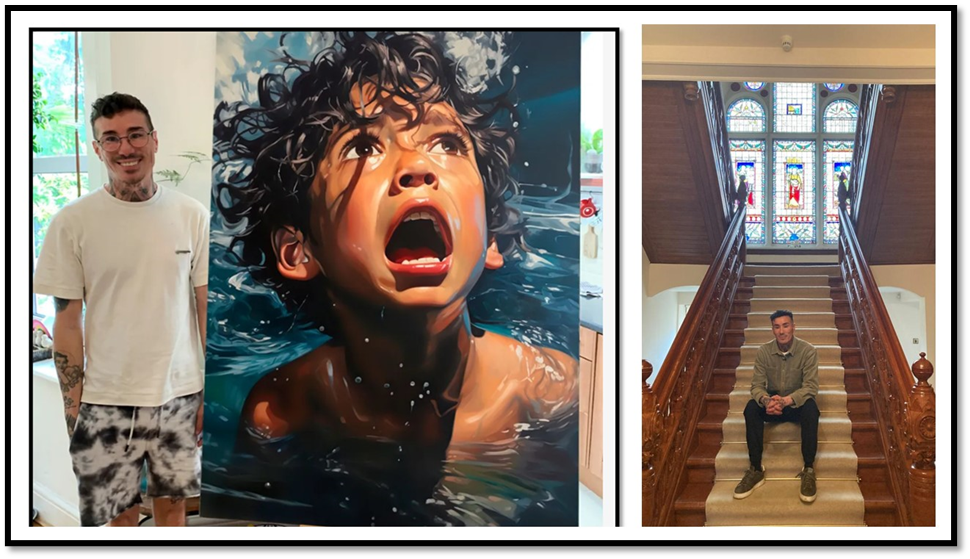

But another reason this is not just about the emergence of queer identities, is that its main lever of change in it is the practice of art, either formally or informally, and the development of an ‘artist’. Hence, its key venue is Kelvingrove Museum, where Juano finds sanctuary even when homeless. In areas around the Museum, a park of course and gay cruising place at night, he finds a ‘homeless man lying on a park bench’ as a model. In this man’s abject state, in the eyes of the people Juano observes observing him, he finds the fire of his own disordering creativity and ‘beauty in the movement’ of the man. Maybe, moreover, the beauty of the book is that everyone in it helps Juano to his beautifully destined being, or so we feel, as in this chance sight in the street where Juano is at his lowest. John notes of the homeless man now ranting at a cruel world such that “his hair flap flops in the wind like a tattered flag… His arms are like brushes, creating a frenzied masterpiece in the air.” The artist is now in the making, and the homeless man is himself an artist bearing paint brushes, or so it seems.[46]

Even when Juano fails to sell his art for a living, he uses it to develop a carapace to house his identities and explore them, combining sketching with identity search:

In this diverse and bustling city, I am constantly on the lookout for a long-lost relative, someone who shares my blood and my story. I watch people like a voyeur, soaking in the details to sketch when I am safe to do so. Maybe I have drawn my birth mum without even realising.[47]

Portraits of, and including the artist, in their studio: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c4nxlv40lv5o

In his excursions further East, he admires the Glasgow School of Art in Sauciehall Street. He envies the role of the ‘Glasgow Boys’, naming James Guthrie in particular as a ‘self-taught’ example like himself in seeing his work at Kelvingrove.[48] I can go no further than this with this theme however. I do not know Juano Diaz’s art well enough yet, but I will. Meanwhile, I think this book enough in itself to honour the artist: a maker of an art of self-expression that plays games with the truths and fictions that only together form a cogent reality – whether fragmented or defragmented, or shifting between these states.

I loved this book. Please read it. And don’t be waylaid by comparisons, which I, at least find not useful, as they appear in Alex Preston’s otherwise warm and good review in The Guardian.

This is a book about the way that early trauma endures and repeats itself, finding new ways of shaping itself to each fresh iteration of life. “I just can’t seem to find my footing in the world,” John says as a young adult, and we remember him as a small child, his feet mangled by care home shoes. If Douglas Stuart is the obvious comparison, I’d add two more: Alexander Masters’s Stuart: A Life Backwards and Andrea Elliott’s Invisible Child. They are the only other works of nonfiction that have moved me as much.[49]

To term memoir into ‘trauma’ can be very damaging in terms of understanding a book as art, the issue that has dogged other writers writing about the looked-after system or disabilities (often socially constructed ones as with Juan’s Birth Mum) in the capacity of care by parents or their substitutes as their part-subject. Examples are work by Jenni Fagan and Lemn Sissay (both of which I have blogged about). Moreover, art is a fairer yardstick than the supposed transcription of ‘factual’ events (so maybe Stuart is a good comparison) because only art understands truly that the real in lives is fact and fiction at most of their intersections and instances of their use in identity-making, not in a bland serial pattern of events.

But read it, please.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Juano Diaz (2024: 139) Slum Boy: A Portrait London, Brazen / Octopus Publishing Group

[2] Ibid: 101f & 102 respectively.

[3] Ibid: 160

[4] Ibid: 175

[5] Juano Diaz (2024: 1) Slum Boy: A Portrait London, Brazen / Octopus Publishing Group

[6] Ibid 1f.

[7] Ibid: 207f.

[8] Ibid: 15, 16

[9] Ibid: 88, 90 respectively

[10] Ibid: 124

[11] Ibid: 45, 46

[12] Ibid: 55

[13] Ibid: 111

[14] Ibid: 72

[15] Ibid: 75

[16] Ibid: 200

[17] Ibid: 109

[18] Ibid: 81

[19] Ibid: 16

[20] Ibid: 118f.

[21] Ibid: 126

[22] Ibid: 68

[23] Ibid: 77, 156

[24] Ibid: 89, 48 respectively

[25] The death scene is important: ibid: 235

[26] For examples: see Ibid: 9,92, 18, 22, 35, 84, 92, 127, 132,

[27] Ibid: 187

[28] Ibid: 227

[29] Ibid: 70, 162 respectively

[30] Ibid:77f., 87, 19 respectively

[31] Ibid: 150

[32] Ibid: 126

[33] Ibid, 41, 66f. respectively

[34] Ibid: 124

[35] Ibid: 130f.

[36] Ibid 130 – 132. Citation is 131.

[37] Ibid: 24f., 38, 42 respectively

[38] Ibid: 75

[39] Ibid: 66f., 70 respectively

[40] Ibid: 80

[41] Ibid: 114

[42] Ibid: 145, 150 respectively

[43] Ibid: 140

[44] Ibid: 164, 167, 178 respectively.

[45] Ibid: 238

[46] Ibid: 167f.

[47] Ibid: 180

[48] Ibid: 227

[49] Alex Preston (2024) ‘Review: Slum Boy: A Portrait by Juano Diaz review – moving memoir that recalls Shuggie Bain’ in The Observer (Sun 18 Feb 2024 09.30 GMT) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/feb/18/slum-boy-a-portrait-by-juano-diaz-review-moving-memoir-that-recalls-shuggie-bain

2 thoughts on “There is no way that you can read through a memoir like ‘Slum Boy: A Portrait’ by following one unbending line of narrative that you expect to unfold in one direction only, for lives full of deep ruptures in personal experience, and maybe all lives, don’t work that way. Reading Juano Diaz (2024) ‘Slum Boy: A Portrait London’.”