Degas in 1859, as a young artist scoping and sketching the European art on a Continental grand tour, said that: ‘Nobody ever rendered the charm and finesse of woman, the elegance and chivalry of man, nor the distinction between the two, like Van Dyck’.[1] He also, in 1891, according to Daniel Halévy, said in response to a remark of Gérôme that ‘An artist is always objective’: “Objective! … Where is your objectivity in art?”. [2] Did Degas believe that a painter like Van Dyck merely reflected the true nature of sex/gender differences, such as he knew them or that he constructed them in their art? This blog is an attempt to prepare myself for the Discovering Degas exhibition at the Burrell Collection in Glasgow, which I am seeing on its opening day on May 24th, 2024.

The information on the gallery web page.

Tomorrow we are going to Glasgow, the main point of which is to see the exhibition named Discovering Degas: Collecting in the Time of William Burrell, on its opening day on Friday May 24th, the opening day of the exhibition. As yet I have not seen the catalogue and I have not been informed yet that it is available from Glasgow City Life, the organisation which sells the tickets. I like to prepare myself for exhibitions by thinking about the issues it aims to cover. However, since this time, I cannot do that because I have no idea of which paintings will appear there – amongst the 70 boasted on the website from both The Burrell Collections own holdings (23 in total) and those borrowed from other galleries.

As well, I have to say, I really have no sense of how or why the notion of art collection differed in the age of William Burrell than any other historical period, which the title of exhibition claims to be its topic. Hence, these issues must be left to an update after seeing the exhibition, providing they do not reflect merely an interest in historical bourgeois connoiseurship for in this I will find it difficult to find an interest. However, I still wanted to prepare myself. Why? I think there are two reasons, neither of which might be easy to pose as specific questions.

First, I have always had a respect for Degas, stemming from seeing the Impressionist collection in The Courtauld Gallery whilst a student in London in the 1980s. I have to say though that I still, I suppose, consider that ‘respect’ to be a grudging and ill-educated one. I will briefly note those issues before starting on a chosen theme of preparation, since the choice is based on those issues. Second, I first began to query whether I had been incapable of seeing what Degas offered after reading Anthea Cullen’s brilliant book of 2018: Looking at Men: Art. Anatomy and the Modern Male Body.

First, I had, as a working-class student who still found most cultural products alien to him, little or no interest in ballet, and perhaps less in female nudes. So, although I could love Manet’s intriguing clothed female subjects at the Courtauld, the Degas ballet-dancers seemed far from being the ‘everyday’ topics of art people at the time claimed to be the case for a middle-class city gentleman, whilst his female nudes left me cold for other complexly intricate reasons – no doubt in part related to my own sexuality. Moreover, the little people told me about Degas – about his belief in a kind of toxic masculinity of hunting and racing horses, military snd business men and their ideals of self-regulation, jocularly at one with high capitalism in the USA and France. This right-wing character took on most of the stereotyped views associated with the right-wing Dreyfusard, at odds, for instance, with heroes of mine like Zola, including an intense and probably deep rooted antisemitism. What, I thought to myself, was there to like about such a noxious character.

Moreover, these attitudes seemed to be apparent too in Degas’ sexual politics, just as mine were radicalising via reading Kate Millett and being involved with the politics of both feminism, with female friends, and queer liberation (though we wouldn’t have used the term ‘queer’ then). At first, and ignorant, glance these nudes (nudes often captured voyeyristicslly at their ‘toilette’) were, it seemed, destined for the walls of the richest men of Europe and the Americas, their subject apparently dictated by a taste for such in a patriarchally controlled market-place for art. This was even more odious when the subjects were working-class women, which seemed to link the gaze of desire at these paintings to rich male patriarchal exploiters of vulnerable women. It was this misunderstanding – brilliantly addressed by the way by Richard Kendall in a chapter called ‘The Art of Renunciation’ in his 1996 book / catalogue Degas: Beyond Impressionism, which book I have only just read – that got unsettled from its place in my head. Tje first to unsettle it was Anthea Cullen’s book, an expert in Degas.

Culleb still refers to Degas as a paintr of female nudes in her book on male nudes, without focusing on that artist’s few male nudes from the earlier part of his career as an artist and in his academic training. By looking JUST at the feminine focus in Degas’s subject-matter, she argues that ‘looking at men’ by artists in the early twentieth-century in ways that question gendered boundaries was a gift from Degas by virtue of his technical and material experiments in the medium of art, an idea she references from her own 1995 book on Degas:

I have written elsewhere about Degas’ pastels, noting that in his time their colour and matière were associated with French Ancien regime decadence and the feminine, whereas line and tone were considered masculine. I argued that Degas’ vigorou, experimental use of pastel, often in conjunction with other media, transformed this reading, effectively appropriating the feminine sensuality of this pur ‘coloured’ matter to robust masculine ends. He thereby disrupted gendered boundaries as well as notions of what constituted a ‘modern’ medium.[3]

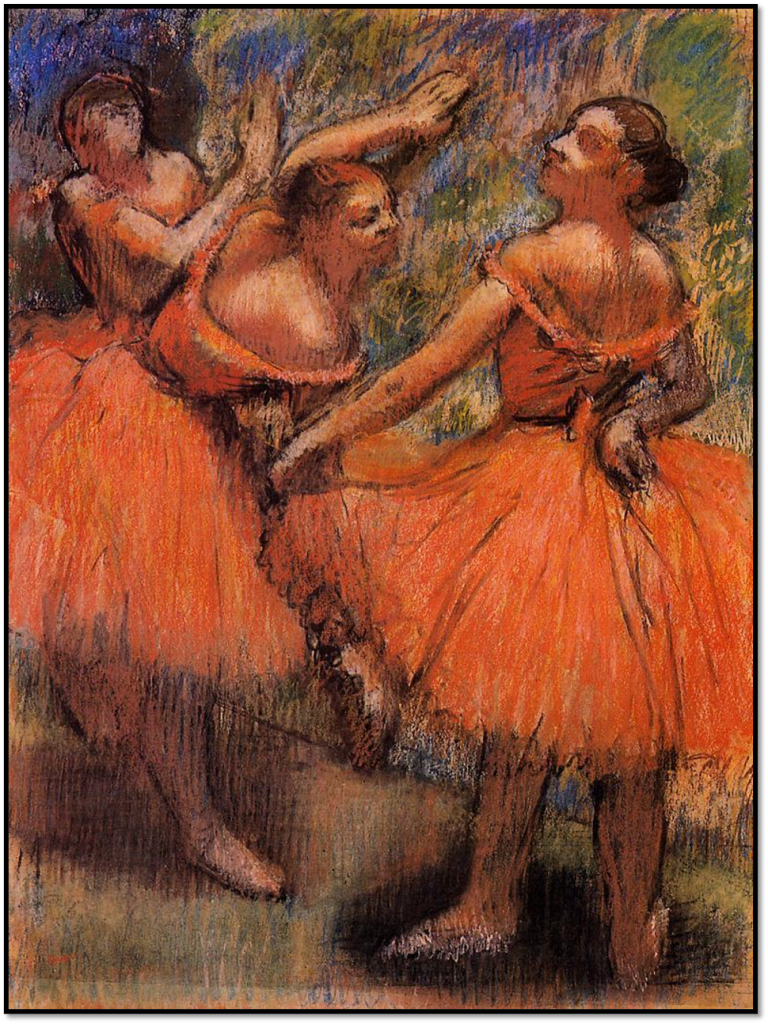

Although Kendall does not reference Cullen, his 1996 book takes similar insights to these further, and in a different way; he, for instance, sees tone but not line as collaborative with the feminised in painting. Kendall cites Degas as often championing, in words at least, a tough line, like that in Ingres, as the basis of graphic figure drawing, as opposed to the soft use of multi-colour in a feminised Delacroix. In practice however, Degas often drew and painted using tonal methods only with multiple coloured pastels integrated with other binding matter, as if he was advancing on Delacroix rather than Ingres and dedicated, not to stability and precision of delineated vision but to what the queer Joris-Karl Huysmans called ‘the marriage and adultery of colours’. At least thos is clearly so in his latter phase – the subject of Kendall’s book. This is evident in one picture I know will be in the exhibition for its is a star of that collection, Red Ballet Skirts (1897-1901).[4]

Edgar Degas, ‘Red Ballet Skirts’ (1897 – 1901). Available at: https://www.jacksonsart.com/blog/2017/09/06/ten-exhibitions-not-miss-september/

I have to return to this picture in relation to my theme in this blog, whose selection as theme I now go on to justify. The aim for me is ,as always for me as a blogger, is its usefulness to my own learning in building initial hypotheses to test, whilst looking at the exhibition next week – mainly in order to encourage my own eye to work for its living.

I have chosen to look at sex/gender in Degas both as an appreciation of his undoubted concentration on a female subject -matter (as recognised by most contemporaries and critics thereafter and summarised by Kendall in 1996 as ‘Degas’s massive and almost exclusive dedication to the female figure’.)[5] Two debates figure here.

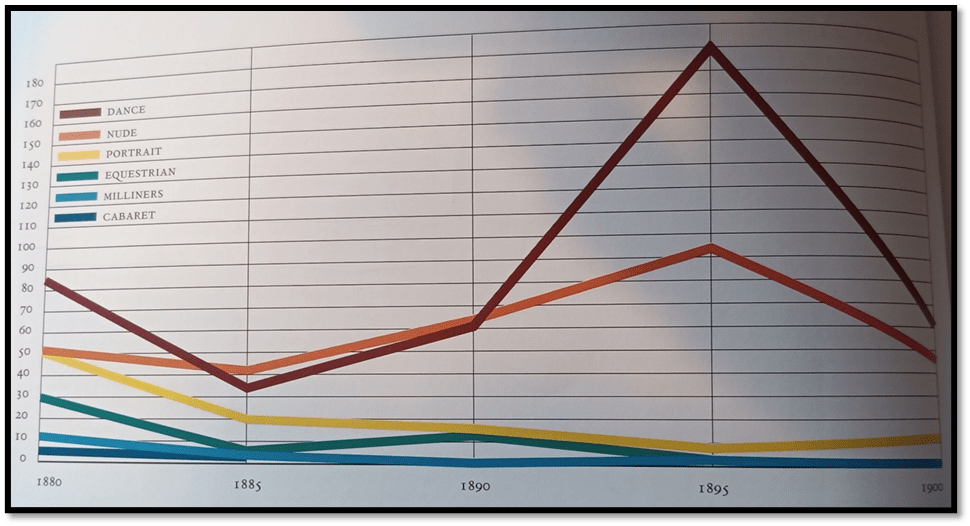

First the insistence on the nude as the proper subject of art that descended through the aesthetic traditions supported by the influence of the Academy, despite Impressionistic resistance to it (mainly in the purely resistant form of Monet). It was also because, as Kendall says, Degas ignored deliberately a new debate raised by the Italian Futurists declaring the nude in painting to be ‘as nauseous and tedious as adultery in literature’. Degas’s continuing use of nudes is charted by Kendall in a graph.

The changing patterns of Degas’s principal subjects from Kendall, op.cit: 126

The evidence might,in this light, make Degas (and so it seemed to me) seem ‘retrogressive, aligning him with the tradition of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts’. Such a view ignores I now see the work of Cézanne and Gauguin in this area (and that was obviously unwise and ignorant of me). People who subscribe to this view often also see Degas as moving from subjects in everyday life to the stock topics of the artist – the female nude and ballet – in his later work.

Second, Degas’s late return to an insistence on the female body as subject, nude or partially clothed, ran against a debate raised by concern about how male artists represented women – for the interested gaze and purpose of men alone. This is a debate in which Degas’ friend, the artist Mary Cassatt, had a role, together with the feminist collector Louisine Havemeyer in the USA. Kendall tells us, moreover, that it was the wives of rich male collectors, who often bought Degas in preference to other European art. Both Cassatt and Havemeyer supported Degas in, as they seemed to think, doing something new and democratic with the female subject in work or domestic poses.

This is a line of argument still in Gill Saunders’ impressive book The Nude: A New Perspective in 1989 which argues the case against Degas’’ ‘alleged misogyny’, in that the pictures show women undressed in ways that do not necessarily presuppose an audience, though she admits there is a case that the women’s innocence of being seen naked or in a place they thought private and testing their own bodies might ‘retain its voyeuristic frisson of forbidden pleasure’.[6]

This is the background of my interest in this blog in the representation of sex / gender both in terms of:

- Degas’ implicit view of the topic appropriate to art and how that topic can be handled in ways that might differ from the past, in the material media employed for instance, especially the use of pastels or innovations in drawing and colour overlay in oils; and,

- The break from views of women entirely dictated by binaries of sex/gender rather than the viewed woman’s autonomy as a human subject, and hopefully participant in the experience of defining sex/gender.

There are lots of ways we can use Degas’ words and his supposed words (‘supposed’ since the latter come from third-person accounts that might not be valid). One of the latter is from the shadowy text Degas and his Model, supposedly written by Alice Michel, which supposedly tells the story of Degas’s relationship to ‘Pauline’, the model for his late pastel nudes of a woman at her toilette. Now nearly blind, Degas sensed Pauline’s body mainly by touch. But he remembered seeing her as a ‘pretty’ if an incompetent model in her early days. She took instruction on pose badly, he thought, and told her that. He mentions in this account that he was ‘the first to see you naked’ (looking ‘chaste and charming’) in conversation with Pauline. And then this exchange:

“Just think! Taking all your clothes off in front of a man!”

“Is an artist a man?” replied Degas, shrugging his shoulders.[7] my emphasis

However we interpret this exchange, Degas here necessarily plays with notions of sex/gender in relation to the artist’s function in representation in ways that one would find unimaginable in Picasso, for instance. In that latter artist, ‘being a man’ is an assertion (often a ‘beastly one) as well as an arena for exploration in which the male gaze is always implicit. This then is where my argument must start. At least it must do so, after recognising that in Degas’ whole career, as so pertinently established by Richard Kendall, we cannot insist that persistence of topic implies consistency and continuity of artistic intention, treatment or interpretation of the topic, as Kendall thinks contemporary witnesses like the poet Paul Valéry did. This is significantly true, he says of his late post-Impressionist period, Kendall’s focus. But he notes changes in the 1860s (towards the ‘nascent’ realist school of Manet, Whistler and Tissot) and then to more autonomy of subject choice in 1870 and thereafter, which itself seemingly gets reversed in the 1890s with a return to classical exempla, but in a manner that has now metamorphosed subjects from their treatments in his earlier career.[8] Of the latter, Kendall writes:

Not only were his professional circumstances and his repertoire of images redefined, .., but Degas’s approach to the practice of his craft was transformed almost beyond recognition. Many, perhaps the majority, of the techniques used in earlier decades were summarily abandoned, …; other processes were substantially modified, both in application and in implicit meaning; and new priorities appeared, overturning long-held values and preparing the ground for the material anarchy of the next generation.[9]

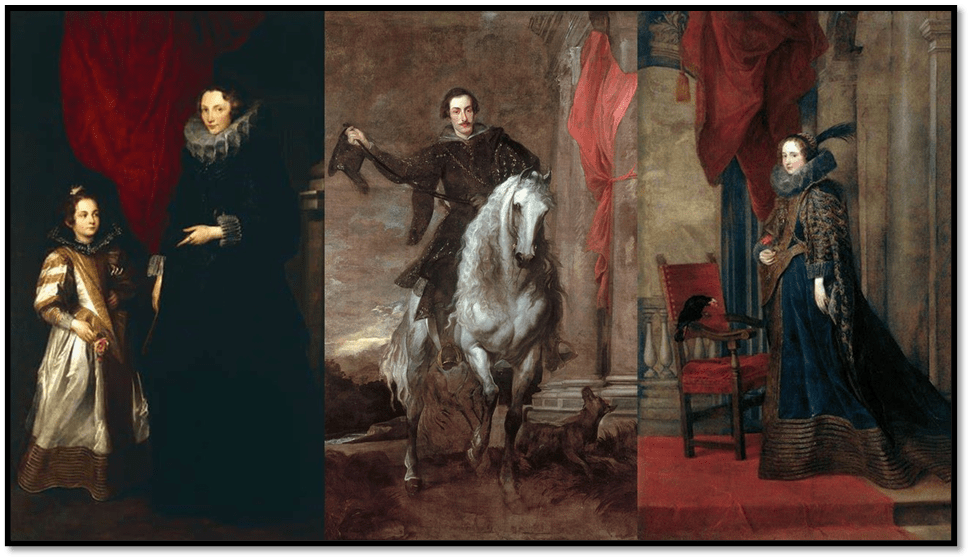

In my title I use contrasting statements from the early and later Degas in characterising how the artist conceived of the aesthetics and definitions of sex / gender in art. My first citation comes from Degas in 1859, as a young artist scoping and sketching the European art on a Continental grand tour, and obsessed by the work of the Italian Renaissance and the seventeenth century, lauding Giotto and feeling the pull of a monastic life. He arrived in Genoa where he said of paintings, ‘in light tones’ in the Brignole Palace that: ‘Nobody ever rendered the charm and finesse of woman, the elegance and chivalry of man, nor the distinction between the two, like Van Dyck’.[10] In the collage below the two pictures to the right and the left of the Count of Brignole may be those of his Countess referred to, though ‘light tones barely describes them’ if colour is the object described as light.

Degas does not mention the male portrait at all but I think it useful to show it, given what Degas says about Van Dyck’s excellence in the comparative ‘rendering’ of men and women: ‘the charm and finesse of woman, the elegance and chivalry of man, nor the distinction between the two’. Hence, the appearance of Count Brignole too in my collage. I think we might at first glance at this sentence see that Degas is commenting on sex/gender differences as if a thing based in nature,

However, the sentence still remains ambiguous enough to perhaps refer to the difference in the rendering of sex/gender that is specific to Van Dyck rather than to the world of the objective truth. Chivalry, for instance, retains its relationship to horsemanship and this is present in the choice of setting for the Count, whilst his wife presents demurely, with ‘charm’ and finish – not at all in motion or on the cusp of it as the Count is. The more I think about this, the more I think Degas is conscious of a difference between man and woman as less inscribed in the nature of sex/gender represented than in the artifices of show and the art of the painter.

Moreover, if this is so, then Degas distances himself from binary characterisation of men and women per se, and attributes the binary attributes to painterly and cultural construction alone, better in Van Dyck (he thinks) than others. I can not prove this, nor do I think I need to, though the preference of drawing men as horse riders early in his career may be analogous.

Whatever Degas thought in the 1850s, however, need not be the same as what he thought in the 1880s and 1890s. His notion of the ‘artist’ as a function without its own sex/gender specification, at least as a man (‘is an an artist a man’), suggests that Degas had begun to see the gaze of the painter as ungendered and not guided by heterosexual desire. The citation I use from that period is recorded in 1891 by Daniel Halévy, a friend too of Marcel Proust. He was apparently contesting a remark by the painter Gérôme that ‘An artist is always objective’.

“Objective! “, Degas replied. What about the Italian Primitives who represented the softness of lips by hard strokes and who made eyes come to life by cutting the lids as if with scissors; and what about their long hands, the thin wrists of Botticelli? … Where is your objectivity in art?”. [11]

These examples are surely remembered, if reinterpreted from the early visits – Giotto being the example of an ‘Italian primitive’ he referred to. The stress is on the facture of the image – the inward and visible signs in it of its making and of the synthesis of subjective distortions that appeal to some idea of a painter, such as Botticelli. This is not the thinking of a man or artist who in practice was not aware that the making of appearances and distinctions of sex/gender were not ‘manufactured’ by the artist and related to his construction of sex/gender and the cusps that separate them.

There is no doubt that Degas was as reactionary in his sexual politics as in other things but a notion of two versions of Degas has now become commonplace, in art history via the work of both Kendall and Anthea Cullen. In part this is because Degas splits, on the one hand, the world of the innovative facture of art from increasingly diverse materials, from, on the other, the public persona of Degas the anti-Dreyfus and antisemitic French gentleman with half his heart in the myths of the Ancien Régime and Bonapartist Neo-classicism on the other.

There is a cusp between all binaries in Degas’s art work,caused by the interaction of overlayed paint on the boundaries of patches of colour, the replication of one drawing upon other drawings of the subject in line line drawing such that overlaps provide a thickening and softening of the line that would have been unitary and crisp when used by Ingres, and the natural run-in of pastel pigments used alongside each other in various ways, including the use of over-washes.[12] Such approaches often allowed colour to be a starting point rather than an embellishment as Ingres would have had it – the soft, obscurely boundaried, and mixed together, taking precedence over the hardened form.

Kendall puts it rather beautifully thus in describing Degas’ conviction that ‘unity depends on the underlying ébauche, linking together the diverse elements of a composition through a single tone and establishing its dominant lights and shadows from the beginning. When he spoke about painting, Degas often stressed this ‘ensemble’,…’. [13] But note that the ensemble is not that of overall composition as such as the interaction between elements of composition and facture within the painting’s detail. This Kendall examples through Nude Woman Drying Herself and Red Ballet Skirts.

This was so of sculpture also, an art Degas saw as integral to painted form. The point is not the artist working on the sculpted nude, for instance, to make of it an idea in a viewer’s mind, generated first in the mind of the artist, of the object of its desire. In the memos of Thiebault-Sisson, he is recorded as saying:

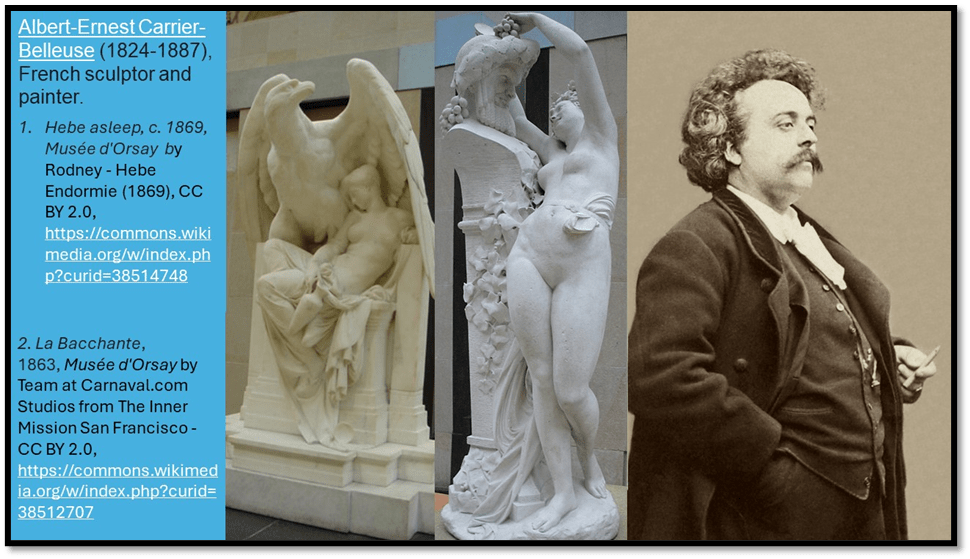

… can you see me bending my studies of nudes into attitudes of false elegance, like Carrier-Belleuse? You will never catch me … revelling in the palpitating flesh that you critics are always caressing when you speak of the academic sculptors of the Institut. What matters to me is to express nature in all its aspects, movement in its exact truth, to accentuate bone and muscle and the compact firmness of flesh. My work is no more than irreproachable in its construction. As for the frisson of flesh – what a trifle![15]

It is helpful to see some work by Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse in order to understand this comment. The female body is bent by the artist to catch the male viewer’s eye and to ask that same eye to caress rather than perceive the complex interactions of flesh, fat and muscle in the body in its own right.

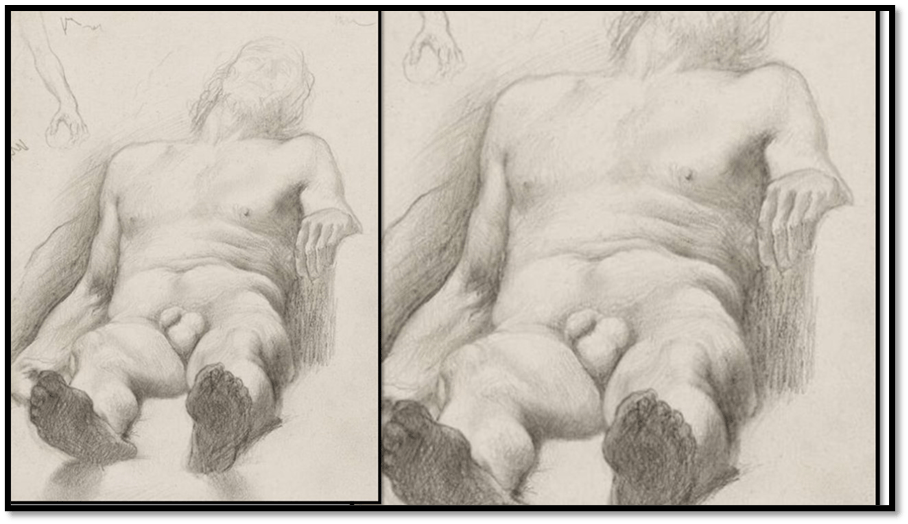

Yet, I have to say that, I still feel uneasy that Degas abandoned the male model – nude or otherwise after the 1880s. One would expect an artist who is ‘not a man’ by Degas’s uncertainly attributed statement to Pauline to sometimes want to see men as materially as he saw women. Male nudes occur but in his early career. They are stunning drawings but their their excellence is that of the Academy as in the two collaged below:

Nevertheless, the later example here (on the left) has considerably less relation to the classical nude, an idealised form created from the mind alone perfecting what it sees, than the one on the right from 1856, I think. The man is physically more fleshed out, his penis appears and is not of the type of the Classical nude, being thicker and more prominent but nevertheless collapsed. The knees have distinct knobbles and the resistance of the raised fist seems to contest the effect of the body being sequestered into a corner, as if by violence. Yet there is very little in either that is not an academic study. I would say that what differentiates the second most from the classical ideal of the male nude is the hint of vulnerability, and of weakness, despite a motion of resistance.

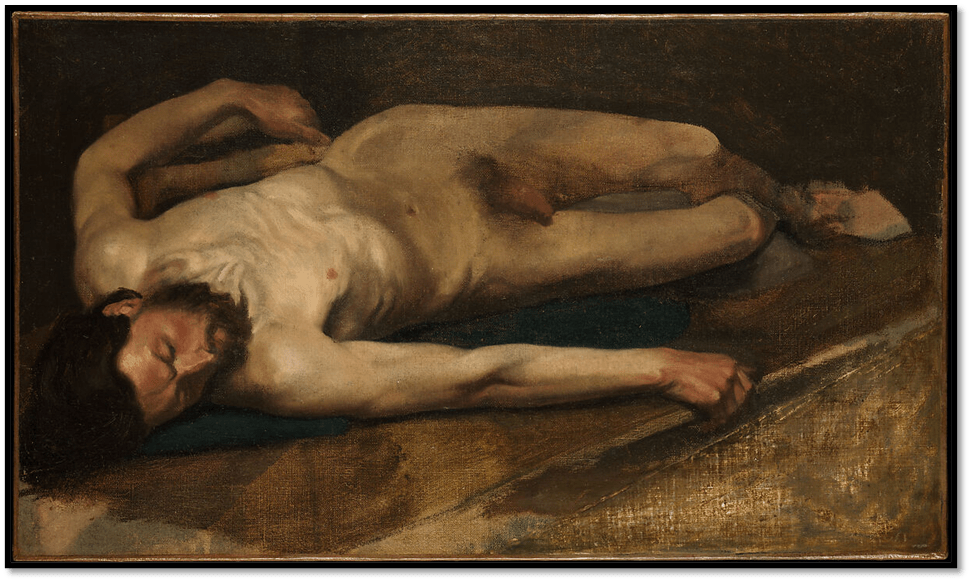

The study of a Reclining Nude (1956-8) below could also be an academic study of the male body in perspective, yet the posture seems that of death rather than sleep. The body is as composed of solid fat as muscle and again a flaccid penis is prominent, if overshadowed by the direct gaze on the testicles, which are made to appear huge in perspectival comparison as with the feet.

All of these examples may fit with the tutelage to Ingres, via one of his pupils in whose atelier Degas worked, but I think it rings bells with me with the way Anthea Cullen speaks of the classical nude as it developed after the politically commanding and suggestively potent classical and virile examples drawn by Ingres. Cullen says that in this period: ‘The classical body is of vital importance as a dominant paradigm not just for its embodiment of an ideal of ‘whole’ manhood, but also because it contains its opposite: the fragility of masculinity’.[16]

His painted male nude of 1856, however, is very unusual, as if it were more certainly than the above, a painting of an anatomical copse before it is worked upon, an exceedingly broken virility:

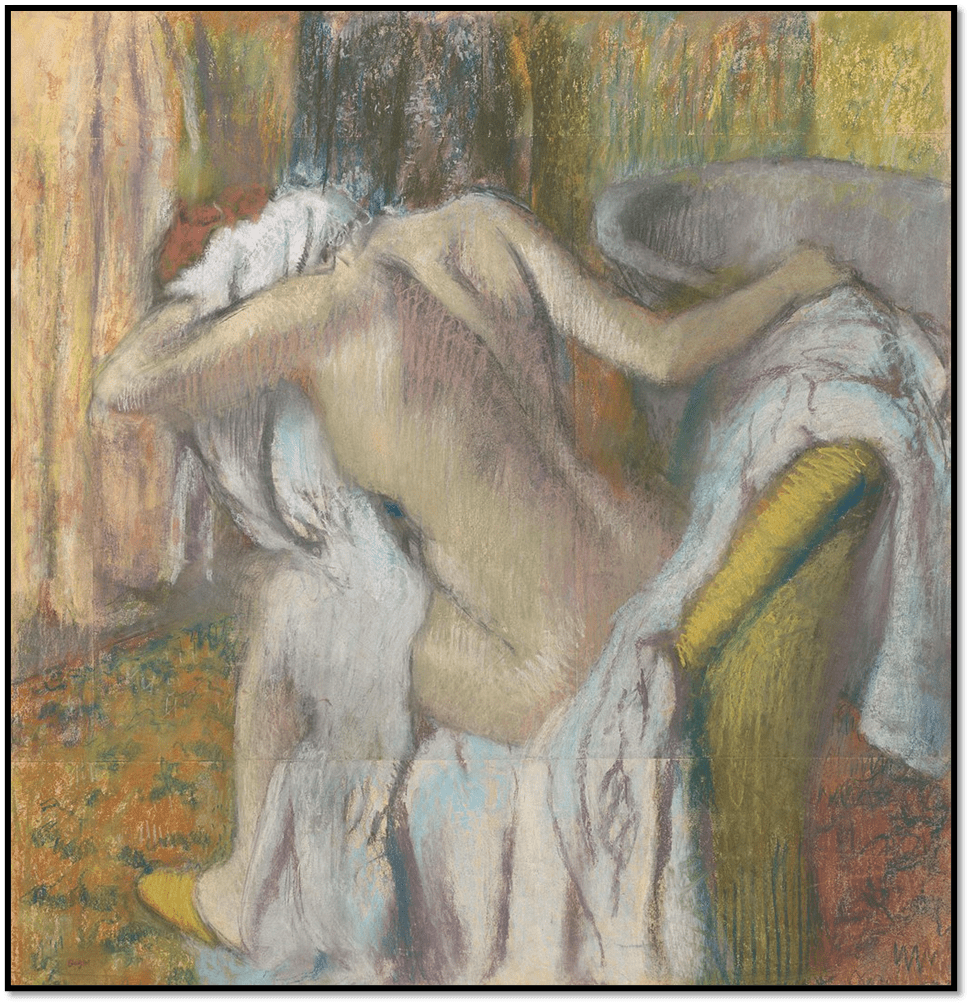

This time, though there is an undeniable prominence given to the penis, it seems merely a dead appendage. The stomach of the man seems to have collapsed into a concavity. The trend of the last two male nudes is to see the male nude as a negation of a male ideal. As I read more about Degas, I begin to feel that his pictures become a means of re-framing the female body as being something other than the caressable object offered up to male eyes by the Academicians like Bouguereau. The male-artist who might have fallen into being the mere holder of the gaze men are ideologically trained to directs at naked women in order to seek more power over them is confronted in Degas by women who do not offer themselves to this gaze but are absorbed in their own self-sufficiency and world.

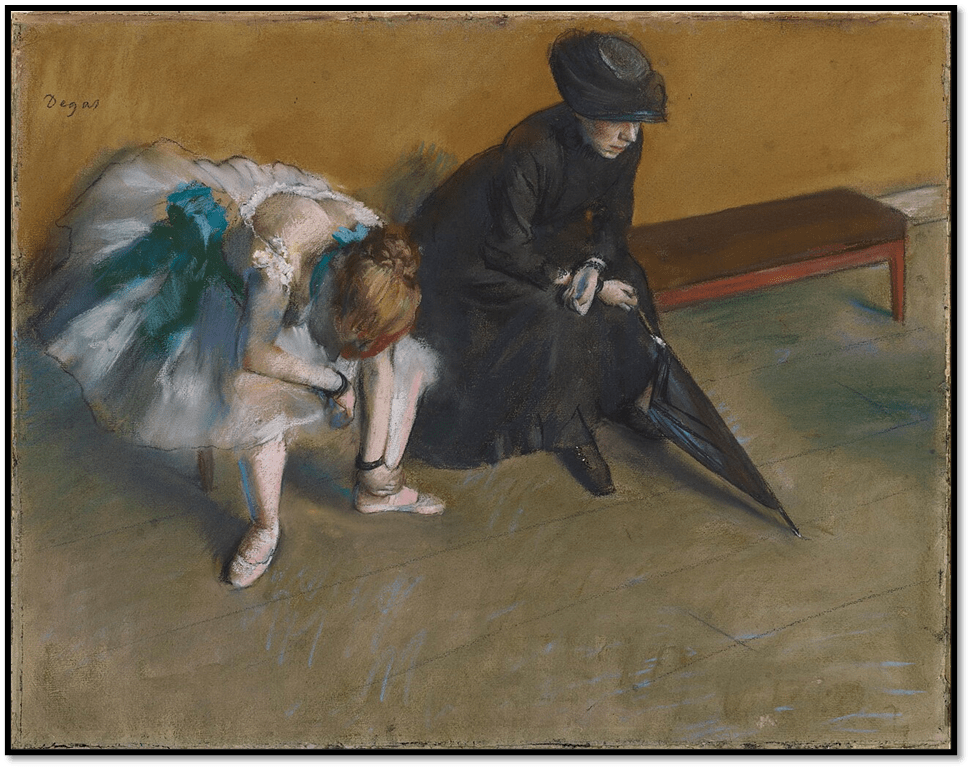

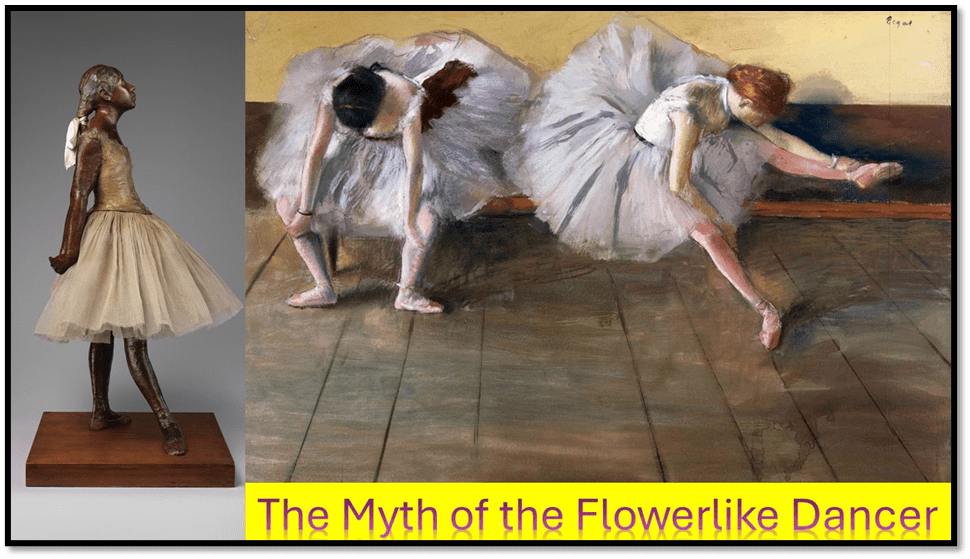

This then is the thesis I want to take to Glasgow to test. Though early in his career he could reproduce the brothel in painting, his later laundresses or milliners are of a piece of presenting women not as objects of male desire but as workers, and later observed in self-absorbed self-care for her own reasons. it matches the earlier social realist interest in the pictures of woman at work, often expressing the effects of overwork and lack of rest. And, truth to tell this is the interest involved in the late ballet-dancers, whom we see often in arduous rehearsal of a body strained beyond nature, attending to strain in their limbs and in inelegant postures, rarely facing the viewer or wanting to be aware of the viewer as in the 1882 painting Waiting or Two Dancers Resting (after 1879) and often taken as a subject in late pastels:

These are not women who men mistake as fragrant flowers. Though Degas’s preparatory sketches painted them in the nude, it was always in order to erase the nudity with ornament leaving fragments of the whole body, and often fragments under stress like an aching limb. The eye that saw those things itself became increasingly aware of his most feminine rather than masculine ways of recreating what it saw, and most commentators equate the use of pastels with a feminisation and softening of the gaze, even where it captured postures thought raw and ugly in classical traditions – postures like resting, squatting, autonomous torsion of the body regardless of apparent aesthetic effect. The late nudes at toilette are classic examples:

Edgar Degas ‘Woman Bathing in a Shallow Tub’ 1885 Available: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436127

I still have to say, though. before I attempt to move on, why Degas might have wanted to challenge male vision, especially in the subject and treatment of art. I think, at the moment, but I need to think about it more, that it may relate to Degas’ perception of aestheticism as a means of failing to respect the embodied real. He saw this problem in Ovid, according to Halévy recording a conversation in February 1897, whose ‘false flowers’ he uses to characterise the artificiality of modern aesthetics and social interaction: ‘everything that’s done today, everything that’s thought is as false as those flowers without leaves, without stems, without roots. It’s artificial’.[17]

At times this rhetoric became homophobic, as well as intolerant of the young. The old ‘celibate’ as he liked to think himself, often compared soft young men to his preferences for ‘work, business, the army!’, However this curmudgeonly self-presentation in public clashes with his constant endeavour in the artist working alone in a studio to feel what it really is like to be ‘inside’, as a sentient consciousness, a woman’s body through the drama of his interacting soft media. This is not the usual desire ascribed to males to be the one penetrating that body but to feel as already with the experience of being penetrated by true vision. He had a distaste for aesthetic queer men like Gide and Montesquiou ( the model for Proust’s Baron de Charlus). He equated ‘taste’ to pederasty, Halévy insisted. Degas actually included in a speech, where Montesquiou was present and showing off his new design of an ‘apple-green bed’, the phrase, ‘Watch out M. de Montesquiou, taste is a vice’. Is all this the over-protestation of a man who never resolved his sexuality, turned to sour over-regulation, I wonder? His expressions about queer aestheticism often turned on punishment. Going to visit Oscar Wilde with his friend, Bartholomé, he said: “So much taste will lead to prison”. Halévy actually quotes an exchange with Wilde that stressed this very thing: seeming to see Wilde’s fault in the courting of publicity to himself:

Wilde: “You know how well known you are in England- “

Degas: “Fortunately less so than you.”[18]

Let’s return to Red Ballet Skirts however:

We can try to read this painting as an objective vision of the interaction and motion between three bodies, but here as elsewhere we are often stymied at the point where we realise that the figures have eyes that seem as nearly blind as Degas’s were becoming at the time. The surface of the paper, pastel washes, often overlapping and clear striations of the colours all form interactions as marks on the paper. In doing so they convey motion in the flow of the ballet skirts jut as if it were analogous to the motion of the hand that brought those strokes and rubbings of colour to bear.

The cusp of objects is confusing, as fabrics often is to perception. We ask whether what we see is one person or thing or article of covering, or setting or background interacting. The vibrant pattern seems to be made to flow by the motion of the dancer’s arms. The frequent use of a flat palm in a hand in Degas either indicates a hand resting on a wall or creating that illusion as in French mime (a feature of ballet). The use of diagonals creates abstract shapes of an open-ended nature on the surface of the picture that counter the representative mimesis of a knowable scenario. The third dancing figure seems lost to any clear perception, except in adding to a series of inverted triangular shapes crossing the top of the pastel.

The rhythmic waves of colour that fringe and / or bridge things represented on the canvas give a musical feel to those patterns; though it’s a music I find deliberately jarring and disturbing. For me, the blinded eye shapes of the figures echo with the deep concavities in perception on the whole – on the floor, perhaps the form of shadows, but if so, from a queered angle of falling light that disturbs. So does the triangular gap between the torso and the hang of her red skirt in the figure in the middle figure in our vision. That latter draws my attention to a similar black cusp between the edge of the dress on her torso and the striated flesh above it.

It is a picture in which what is real and apparent – for these figures are in the process of learning not just dance but an enactment of a role, which forces a viewer’s response to be as if they were in part the emotions that these figures share between them in the pain and joy of the work, in their isolation and group-feeling. It is a range of feelings as often on the cusps between things as the graphic design of the whole picture.

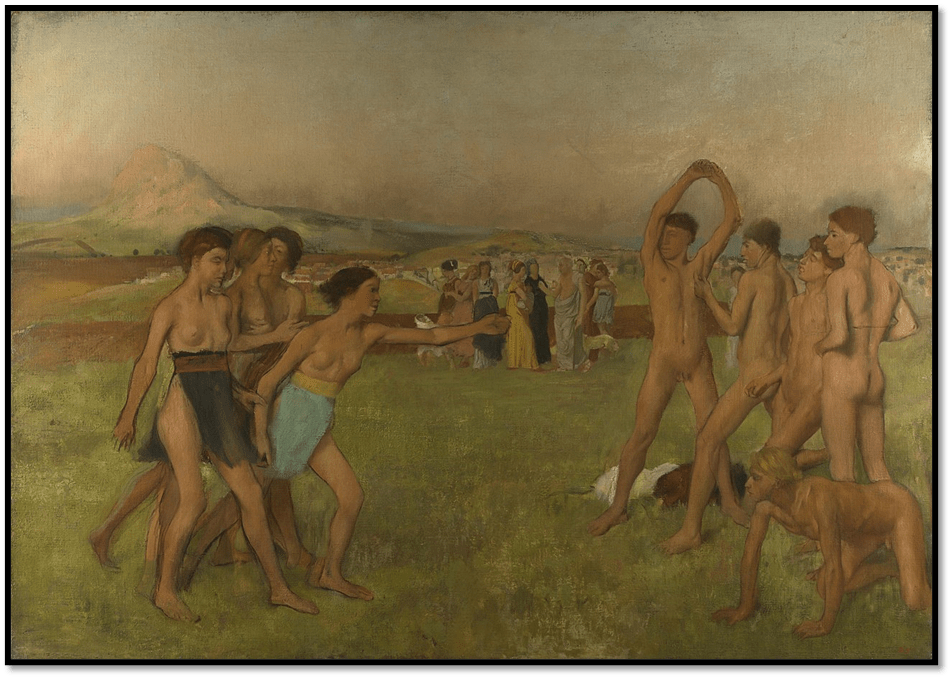

After I look I find myself saying: is the artist a man? Am I? Is that indeed the kind of question hanging between the Spartan youth in that famous earlier Degas painting. Moreover, if I were either or both a man and woman would it determine what I want, which Freud used to think only a question to answer in relation to women. It would not, of course, for Degas knows what Winnicott knows; that sex/gender is realised in dreams, and artists dream in loud colours. Perhaps he was right to be clear that he differed from Oscar Wilde, as I read it, only in the desire not to well-known: even to himself:

Geoff and I travel to Glasgow on Wednesday for a play on Thursday (its sold as A Play and A Pint) about a queer young lad who is deaf. It will be shown in a room covered with wall murals by the wonderful Alasdair Gray (in Oran Mor Church at the top of Byre Road). Then on Friday the Degas exhibition opens at the Burrell Collection at Pollock Park, we will be there and I will report back. I will let you know if my musings helped me or the reverse.

All my love

Steve xxxxxxx

[1] From a letter to Moreau (26 April 1859) in Richard Kendall (ed.) [2000: 26] Degas by Himself: Drawings, prints, paintings, writings London Little, Brown and Company (UK).

[2] From Halévy’s diary (17 Jan. 1891) in ibid: 216.

[3] Anthea Cullen (2018: 213) Looking at Men: Art. Anatomy and the Modern Male Body New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

[4] Richard Kendall (1996: 100f. & 104 respectively) Degas: Beyond Impressionism London, National Gallery Publications

[5] Ibid: 144

[6] Gill Saunders (1989: 25f.) The Nude: A New Perspective London, The Herbert Press.

[7] Richard Kendall Ed. (2000) op.cit: 316

[8] Richard Kendall (1996) op.cit: 62f.

[9] Ibid: 59

[10] From a letter to Moreau (26 April 1859) in ibid: 26

[11] From Halévy’s diary (17 Jan. 1891) in Kendall[ed] op.cit: 216.

[12] See Kendall 1996 op.cit: 121f, on the Venetian palette, 71-4 on replication method in line drawing and 104 – 113 on pastels.

[13] Ibid: 112

[14] Cited Kendall (2000) op.cit: 228

[15] Ibid: 246

[16] Anthea Cullen op.cit: 26

[17] See Kendall (Ed.) 2000 op.cit: 241

[18] Ibid: 238

One thought on “Reflection on sex/gender in painting before seeing ‘Discovering Degas’ at the Glasgow Burrell Collection.”