James and John, due to be executed for ‘sodomy’, were visited by Charles Dickens and the editor of the Monthly Magazine for which he wrote under the pen-name, Boz. He wrote in his coverage of that visit of the look of men who ‘had nothing to expect from the mercy of the crown’ and who ‘well knew that for them there was no hope in the world’ that one stooped over the fire, another sunk his head as he rested his arm on a mantelpiece. He emphasises the melodrama, of the man standing he says: “The light fell upon him, and communicated to his pale, haggard face, and disordered hair, an appearance which, at that distance, was ghastly’.[1] This is a blog on Chris Bryant (2024) James and John: A True Story of Prejudice and Murder London, Bloomsbury Publishing

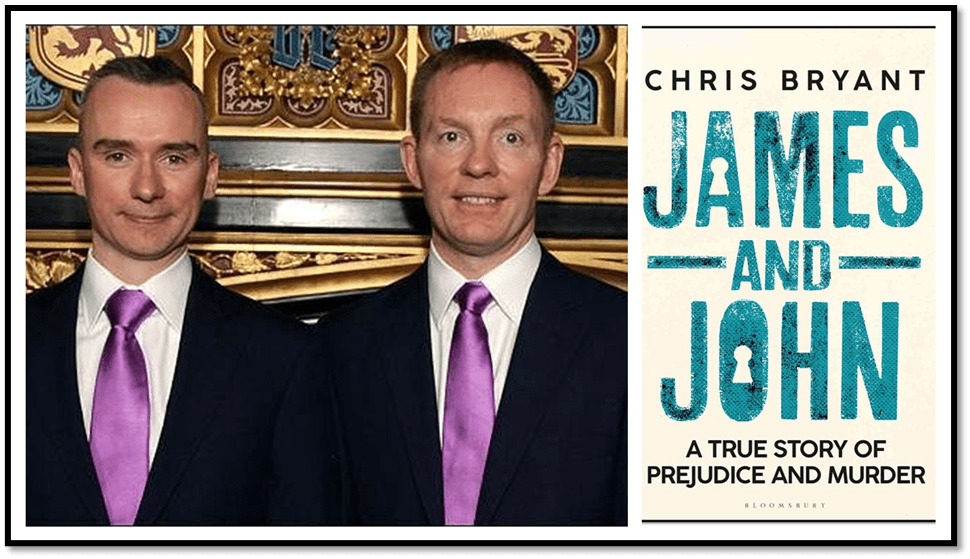

Chris Bryant’s popular and well-written books on queer history are mentioned too in the following linked blogs: On the Glamour Boys & On The London Bath-House.

Chris Bryant tells stories from queer history very well indeed and this book was for a page-turner of a history – mainly because of the comprehensive way the writer captures a cast of characters from different social classes and status, who had a role in the story of judicial murder he recounts. The few critics of the book I read are, however, divided on the effect of this. Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian assumes Bryant does this merely because there is a ‘thinness of the material’ from which to work to flesh out the two central characters, James Pratt and John Smith. Hence, she continues, Bryant conjures ‘a word picture of pre-Victorian London’. It gives ‘a certain social density’ she concedes but it more importantly dislodges ‘the story of James and John from its proper place, at the heart of the story’.[2] I disagree, as does the Tory peer and journalist, Lord Black, who argues that the book is not driven by one heart at all but is instead two books in one.

The first is the heart-wrenching tale of two ordinary working men – James Pratt and John Smith – who committed, as one foreign observer put it, a “sin regarded in England as more abominable than any other”. …

/

The second book is an exquisite social, legal, ecclesiastical and political history of Britain during a period that was both an “era of bloodthirsty prejudice” and of profound change. … And we get intimately to know London in the 1830s – from Fagin’s Clerkenwell to the slums of Deptford where James lived, via the “cruising areas” of Hyde Park, the scene of regular entrapment of gay men. It is a fascinating read, meticulously researched.[3]

Hughes indeed seems to miss the significance of all that ‘social density’ that submerges James and John. There is a lovely moment when Bryant shows us that these men were playing their part in front of a backdrop of another drama, wherein the elected sheriff of Aldgate ward the city, David Salomans, was nervous because he had been objected to by the antisemitic rival he had defeated at the election having raised a banning order against the Jewish, and progressive liberal, victor. This would not have mattered had there not been a change of ceremonial protocol by which he, and his colleague, Alderman Lainson, both had to ceremonially escort each of the condemned to the gallows in their ceremonial robes. Salomans must have felt in the charged atmosphere of antisemitism that the crowd hissed at him as well as the condemned. Bryant says:

James and John probably knew little of these events and cared even less, but this was the first time Salomans and Lainson had been required to escort the condemned men to the execution.[4]

There is a lot of licence in the interpretation of the feelings of all here, but how much more ‘socially dense’ the event becomes as a result, despite Hughes’ strictures. The fact that James and John were themselves shut out from full knowledge or ability to appreciate the events around them actually rounds their representation more despite the absence of valid documents to prove their feelings. And we can see that not appreciating this fact makes Hughes mistaken about the book she reads.

For instance, she summarises the history of the treatment of sodomy law charges at the time of the book thus:

In recent years there had been a softening in public opinion towards penetrative sex between men which, while “wicked”, “diabolical” and “against the order of nature”, no longer seemed to require the ultimate sanction, especially when their crime had involved neither violence nor theft. It had been more than a dozen years since the privy council had ordered a similar execution for the crime at Newgate Prison.

Quite what made the case of Pratt and Smith different is hard to say. Neither had ever been in trouble with the law, and were not the kind of men that the public tend to particularly dislike. ….

This almost tells the story Bryant tells but misses the nuance so well understood by Bryant, who has reason to understand the oppression of queer men past and present, that the case was prosecuted in part with a view to make the sodomy laws a more precise tool. She misses that in this case the Crown had, or believed it had, evidence of defining features of sodomy under the law, so often missing from the prosecution of sodomy, that was legally required to be proven. The evidence required was of the fact that penetration of a body orifice actually occurred and that there was emission of semen (or seed as the court would call it), To the fact of these the renting landlords of the flat James and John had hired, the Berkshires, both testified to seeing those events occur whilst each followed the other to view it through the keyhole. We need social density to see why that mattered, to secure a safe ‘delivery of justice’ in an area muddied in the legal past at certain pints of certain judicial persons carers, especially that of Charles Ewan Law, a character you believe you think you know by the end of the book.

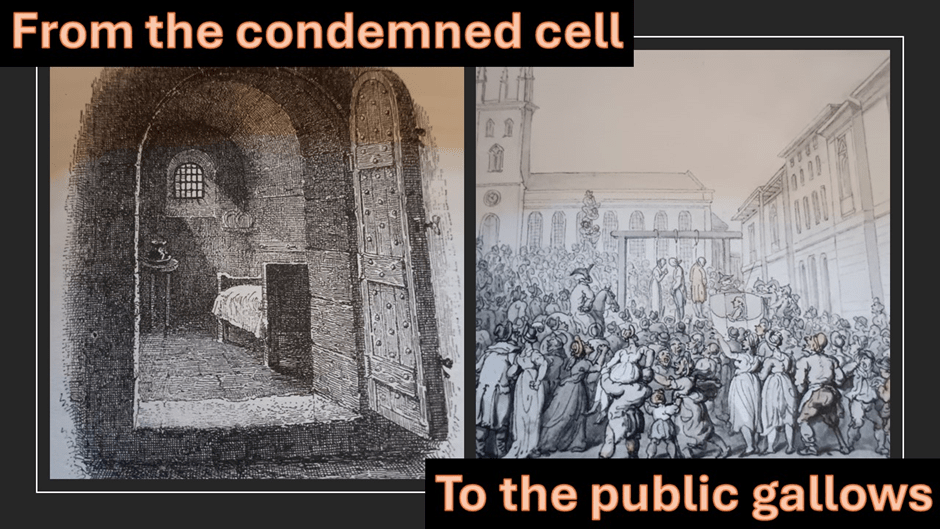

Hughes oversimplifies by looking at soft and hard individual attitudes in the socio-legal system, though these matter too, and not noting that to people at the time their belief in the righteous of their conduct mattered, however misguided. Knowing all this, makes it no less the ‘judicial murder’ Bryant calls it but we do see it as an event whose mechanisms were driven by complex psychosocial factors. And the two condemned men come across richly – their lies and their truths all bound in densely human and socio-political real events, of which the men ‘knew little of these events and cared even less’. For of such are queer histories made. Lord Black is also more correct in implicitly suggesting that the two books together, as he sees them, of this one book make it what it is: ‘a harrowing story, beautifully told. It makes painful reading: the faint-hearted should beware’. You must beware if you are faint-hearted because part of the social density comes from some fairly graphic description of the ‘art’ of the hangman, as illustrated in stories of hangings for either sodomy or theft, or many of the things the state could hang poor people for. The means of death under constant errors in the process are graphically described. James and John’s hangman, Calcraft, had a bad reputation, for both error and for cashing in on his role, and communities like Newgate would have conveyed the stories that proved that to James and John. We intuit their fear from that and feel it ourselves from the meticulous detail given to us in the book.

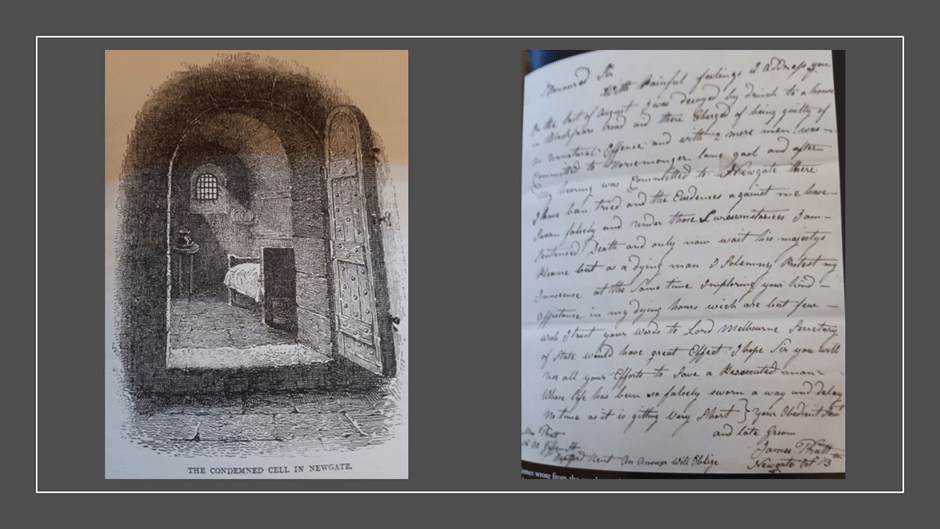

And to see the letter that James Pratt sent to someone he hoped would secure lenience or acquittal of his death sentence in the book conveys not only the depth of lying that Pratt had to use to convince not only his wife but himself of his innocence of non-heteronormative acts can only be appreciated if we know the actuality of the means by which the control and regulation are not only articulated but practiced by real people, institutions and communities of prejudice and interest, including shadowy communities of the marginalised non-heteronormative. See the letter:

The beauty of the book is that it unearths the reality of secreted sexual meeting places for queer men and the commonness of knowledge about them. The state and church may have bruited the evil and repulsive nature of queer sex but the popular imagination often received these unearthing of sexual action as a matter of social fun. The hangings indeed may be hissing places but hissing at outcasts is perceived as fun in some ways and hangings were festive things, with food and toy stalls and lots of room for unexpected drama from a poor practitioner like Calcraft.

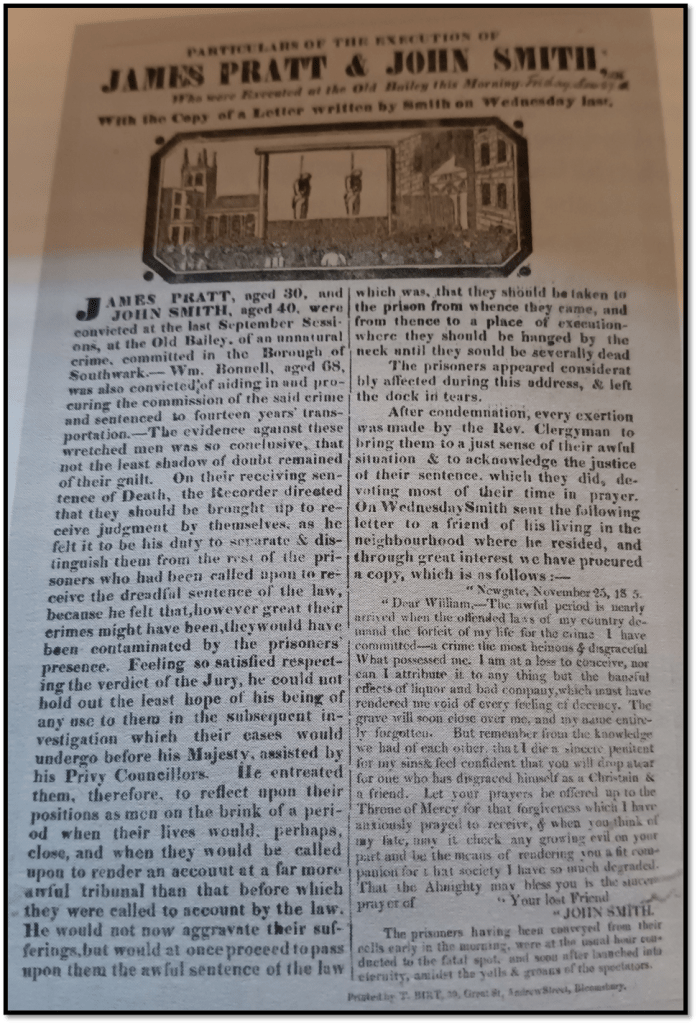

The popular press could make a saleable broadsheet publication as was indeed made in the case of James And John:

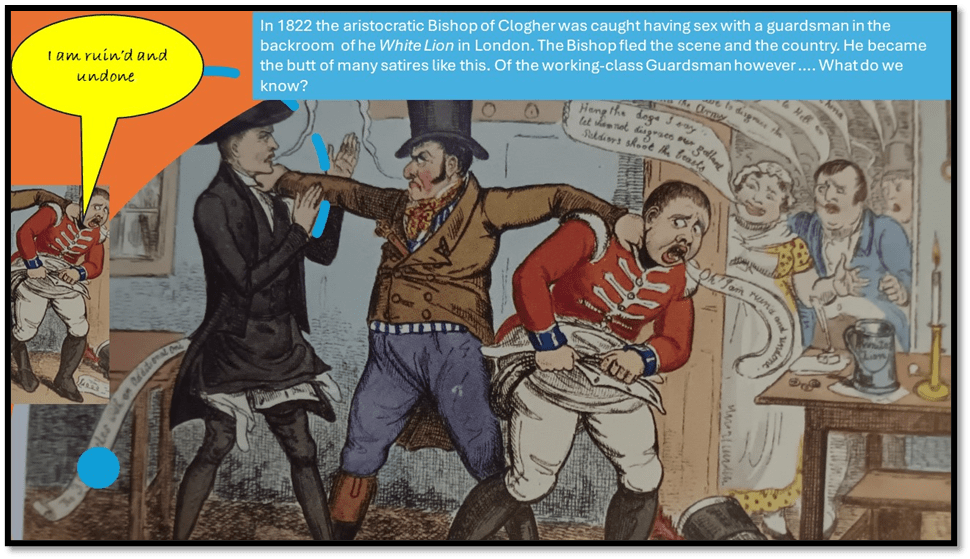

Such publications combined horror at the crime while stoking up fascination in it. Sometimes, and especially when the target was Establishment figures, fun seemed uppermost. Note this example provided by Bryant:

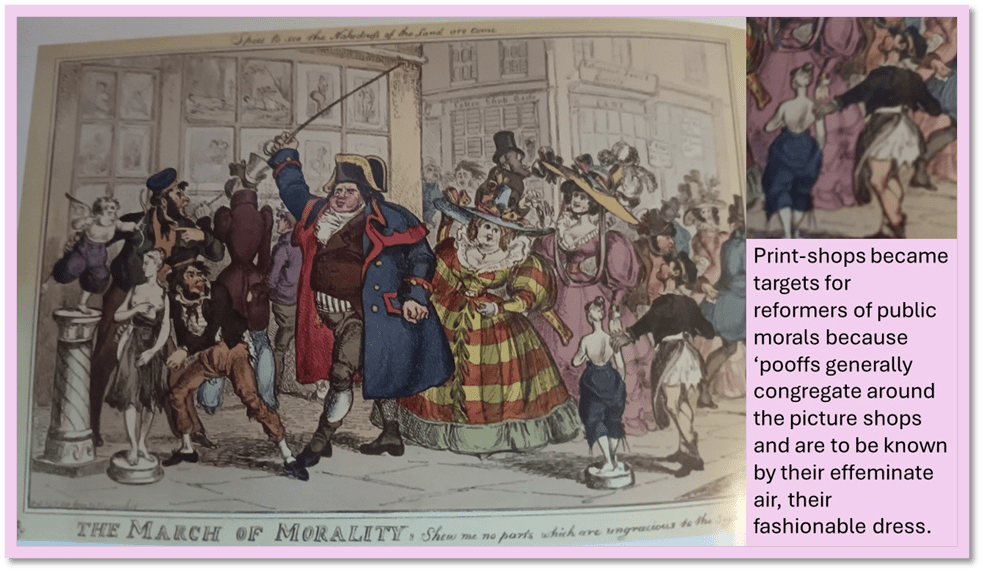

The Bishop caught with his pants askew, spewing from them ecclesiastical hypocrisy whilst offering the officer a bribe was to the popular taste. There is more of fellow fun with the working class guardsman caught out being naughty and earning himself some money on poor pay. Such scenarios were part of the popular imagination. Indeed certain moralists began to blame the print shops themselves for the moral scourge of queer sex. Bryant offers us this wonderful cartoon outside a print shop where gaudy posh ladies are helped visit by a Beadle of the parish to see the ‘pooffs’ and so on outside the print-shop.

Above we see the March of Morality outside a print-shop, with lower-body nakedness particularly targeted in the semi-dressed classical statuettes. The key character is surely the ‘pooff’ standing contrapposto like the classical nymph next to him, whose rapidly adorned front smock hides the fact that behind we see some very short frilly underwear and naked legs meant to be stood provocatively. I think the publicity here is all oppressive, even the fun perhaps especially the fun) but we would not see the complexity of queer sexuality in the period, or any other, otherwise.

That John and James were the last to die for sodomy is not enough to see good news in this book, which also shows you the reality of transportation to Van Diemen’s Land and the realities of the Hulk ships prisoners were kept in before transportation, including their reputation for sodomy full enacted. It gives a new feeling for the Hulks in Great expectations and the relationship of Magwitch and Compeyson.

But we should stay seriously with Dickens in this novel, for he visited Newgate many times as journalist and researching novelist. In my title I cite some of the words he spoke of these men as a journalist. Let’s look again at him observing, for his readers the two men. Both men are as ‘motionless as statues’ ;one stooping by the fire (a very Dickensian thing to do). The one leaning on the mantelpiece strikes him most and he theatricalises the vision for his readers :

“The light fell upon him, and communicated to his pale, haggard face, and disordered hair, an appearance which, at that distance, was ghastly. His cheek rested upon his hand;’ and, with his face a little raised, and his eyes wildly staring before him, he seemed to be unconsciously intent on counting the chinks in the opposite wall.[5]

There is melodrama here of course and it is not of the best of Dickens’ writing – it reads almost like an acting script for William Macready playing the hammiest of melodrama on the Victorian stage – but the aim is to externalise the things inside the man, even the unconscious processes. Even if there be only unconscious motor effects – the look of counting chinks to an impossible outer freedom for instance– they invite us to dive into an abyss. It does all the tricks in prose that Bryant does without. Dickens wanted us to see men who are being torn apart by reflection rather than use it for their potential future. No doubt for Dickens that would have to be a future without sex with other men but certainly he feels men should not only see walls in front of the, though he is ambiguous about that. Think of Fagin in the condemned cell. Dickens is just another witness locked in the sympathies of his time, though more radical ones that that of the system he felt to be strangling everyone.

Bryant conveys the tragedies of the stories he tells by objective context continually intersecting invitations that allow ourselves entry into consciousnesses, through stories about them, that were never used to being that public. It is a book I am missing now it is finished. It is the work of a good history writer – not because it brooks heart and mind but because it sees human experience as the interaction of subjective life with events too comprehensive for any one subject to understand, in layers of three-dimensional networks. It is truer queer history than some histories that label themselves as such, though some perspectives are absent.

Do read it. It is stunning.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Chris Bryant (2024: 188f.) James and John: A True Story of Prejudice and Murder London, Bloomsbury Publishing

[2] Kathryn Hughes (2024) ‘Review: James and John by Chris Bryant review – the cost of being gay in 19th century London’ in The Guardian online [Wed 14 Feb 2024 11.00 GMT] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/feb/14/james-and-john-by-chris-bryant-review-the-cost-of-being-gay-in-19th-century-london

[3] Lord Black (2024) ‘A harrowing and beautifully told story, Chris Bryant’s meticulously researched book about the last two men to be hanged in Britain for being gay makes for painful reading’ in The Home, website of PoliticsHome). Available at https://www.politicshome.com/thehouse/article/lord-black-reviews-chris-bryants-james-john

[4] Chris Bryant op.cit: 232

[5] ibid: 188f.