‘At fifty-two, he knew himself to be a traitor to the class of his youth and a freak to his own moral understanding’.[1]When a literary intelligentsia loses faith in its own social purpose and integrity, the fate of the ‘state-of-the-nation’ novel is to betray the backward-looking values of the perspectives that attempt both to assess the current state of the nation and to steer it towards a sustainable future. This blog reflects on Andrew O’Hagan (2024) Caledonian Road London, Faber & Faber.

Change in London is a constant work in progress. Although, I was educated at the English department of University College London I don’t recognise it from this novel. However, I do sense that the same liberality might rule the relationships of staff and students there, as least as O’Hagan imagines it, for the plot of this novel so centrally hangs around a queer sort of relationship between the protagonist Campbell Flynn and Milo Mangasha, a student of Computer Studies taking an optional literature class with Flynn, and who lives on Caledonian Road, and hence names the novel. We will return later to Caledonian Road for all that it might mean in this novel, other than a source of, at the time imagined, relatively cheap housing affordable by a student.

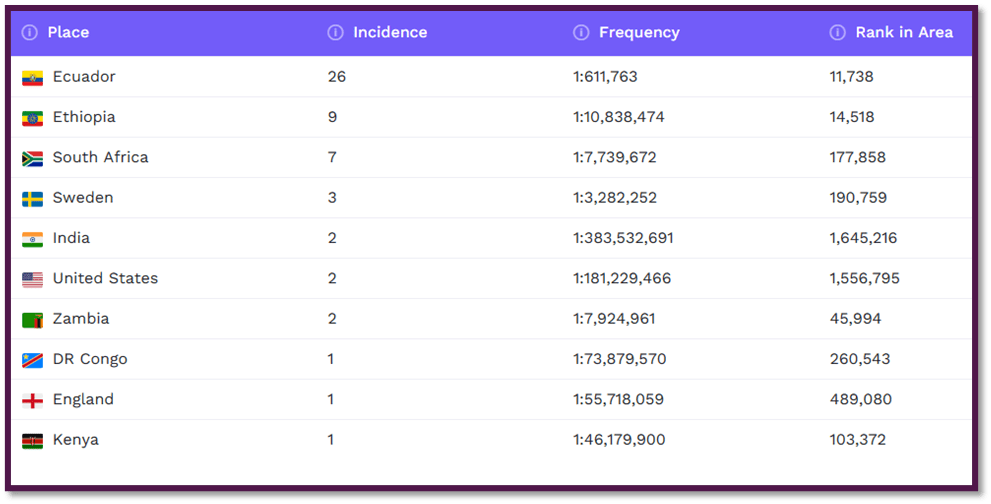

When I call the relationship ‘a queer sort of relationship’ of course, I don’t mean it is at all sexual, though queer-identified sexual relationships do form around the margins of this novel and in some of its characters, and Campbell Flynn chooses a queer actor, Jake Hart-Davies, as the person to ghost for him as the author of his latest book, Why Men Don’t Weep in Cars. Milo is queerly instantiated because he upsets all assumptions you might make about him or ways you might characterise him. Indeed, he is Flynn’s ‘favourite upsetter’: ‘As a student, he was more nervous than he appeared, but could manufacture confidence. He stared a lot, had Irish eyes and brown skin, and a way of resisting every assumption you might make about him’.[2] Well, I don’t exactly know if I could recognise ‘Irish eyes’ though the first name ‘Milo’ might suggest it to be. Otherwise there are few ways of labelling Milo ethnically. Did O’Hagan find the student’s last name where I did in a name finder website, like the one that tells me that: ’The last name Mangasha is the 2,580,327th most commonly held surname on earth It is held by approximately 1 in 130,134,748 people’. The name is distributed unevenly – mainly in Ecuadorean South America and secondarily in Ethiopia:[3]

That the second most common distribution of the name is in Ethiopia is interesting for this is the area chosen to home Milo’s family name – in fact his matrilineal name. Of course, this is because undocumented immigration was more likely from Ethiopia than Ecuador but it might also show the writer choosing a name with an indeterminacy in its origin that is probably crucial for Milo. Campbell’s wife is told a fuller story that:

“The first name’s Irish, from my dad. He was born in Tipperary, My mother was Ethiopian and came to London in the 1970s. Big feminists, so I got her surname”.[4]

So many highly situated evasions of the obvious have gone into this name, from the joint parental feminism onwards. And this makes Milo perhaps a person easy to ‘appropriate’ to serve the vacancy inside Campbell Flynn himself, just as Tudor-Hart is more problematically appropriated together with some inconvenient baggage by him. Milo is, to me, is one of the least satisfactory characters of the novel, together with the paper-thin Polish migrant Jakub and the Russian autocrat Aleksander Bykov. I would guess that this is because each of the latter serves as a type of some issue in the state of the nation (‘small boat’ immigration from European shores and the role of Russian capital in the isolation of the UK by Brexit from its near fair trading neighbours) or, in Milo’s case, an issue or issues in the state of Campbell himself as an observer and symbol of the nation and its contemporary deconstructionist culture, especially the theme of abandonment nearest to his heart and conscience – for the whole novel sees him abandoning old friends or being abandoned by them with quite knowing who was doing the abandoning in some cases).

It is difficult to find anything much in Milo, then, for readers (or, at least, I find it so) that Flynn will not have explicitly tried to find in him for the bulk of the novel. Flynn’s obsession with Milo puzzles everyone including Flynn’s psychotherapist-wife. When he finally realises he is lost to Milo, it is because the boy no longer holds out for him a meaningful presence that can becomes a manner of changing Flynn’s life. The final act is the disastrous speech at the British Museum, in which he likens it to ‘Fagin’s Lair’ (that is, to a home of stolen and appropriated property). He rejects Milo openly because he knows himself already to have been rejected (or ghosted – a contemporary word he probably appropriates from Milo) by Milo himself. It is a story of a kind of doomed asexual affair that ends in bitter, but rather hard to understand charges made against Milo in a letter that seems to project into the young man the behaviour the older man dislikes in himself – that he has abandoned any ‘core identity’, which ought to have meant, any regard for what Campbell’s life is really like: ‘I have spent my whole life, like most people, alone, but I guess you will not see that in your singularity’.[5]

A ’singularity’ is a striking word by which to characterise Milo. Let’s try a net definition – inadequate no doubt but it will move us on:

To understand what a singularity is, imagine the force of gravity compressing you down into an infinitely tiny point, so that you occupy literally no volume. That sounds impossible … and it is. These “singularities” are found in the centers of black holes and at the beginning of the Big Bang. These singularities don’t represent something physical. Rather, when they appear in mathematics, they are telling us that our theories of physics are breaking down, and we need to replace them with a better understanding.[6]

From the very first Milo has said that he wanted to ‘rip up the rules and walk about in other people’s shoes’. The only criterion for the success of either the value of ‘Art’ or the novelty of ‘thinking’, Milo says to Flynn, is ‘how good it is and how fresh’, how much to the older it seems young, to the old it seems new, and to the self-consciousness of the bad past, a current good.[7] And that purpose of moral refreshment is precisely what Flynn thinks Milo offers him. When Milo attends Flynn’s tutorial ‘office hour’ (times when tutors announce their availability to comers in their university office) at University College, Flynn finds he ‘taps an emotion’ in Milo by mentioning the unequal distribution of deaths from Covid relative to social inequalities (Milo’s Ethiopian-born mother will die of Covid related illness, for instance). Having tapped that emotion, he evaluates Milo in terms of Flynn’s own needs as a person, in some finely manipulated prose, where a definitive point of view on events starts off as it were an authorial statement (as Flynn’s prose, of course, WOULD).

Sometimes a young person can give the young person still alive in you a second chance. The boy was working class, like Campbell used to be; the young man wanted to act – and Campbell felt it keenly during the office hour, how a fresh association might replenish him and force him to embrace the change that frightened him.[8]

Campbell seems to wish to feed off Milo’s youth like an Undead vampire feeds off the freshness of the living, accessing young blood into very old veins. And the embracement of change is a kind of embracement that only the queer association will allow him to enter the future in a manner authentic to its rather than to past values. There is no doubt that Milo cannot fulfil this role for Flynn. In my view, this is why the novel has the title Caledonian Road chosen to sound its themes.[9]

Let’s pause awhile to contemplate the history of the Caledonian Road. Its name is itself fortuitous. Here is its origin according to a section in Wikipedia on the Road towards the Great North Road. Strangely it is not named as a reference to the means of leaving London to progress to Caledonia, the Roman name for Scotland. Of course, O’Hagan rather plays with the idea of Flynn looking back through his new ‘Candy Crush’, a humiliatingly ironic description of the Professor’s everyday amusements under the influence of Milo, the Ancestry website to find, whilst he takes a seat at the foot of the Caledonian Road at St. Pancras in the ‘champagne bar, ordering a large Islay malt’, another ‘little increment in the deep history of his family’: ‘All those Flynns, Dunns, Flannigans, Morans, Docherty and Rileys. “Pauper”. “Journeyman”, “signed with his mark”, “died in the Glasgow Poorhouse”. The luxurious reading of the poverty of history (in all of the senses of that term including E.P. Thompson’s) here almost hurts in its through handling of Flynn’s pretensions. Hence , it would be fortuitous nod to the novel’s themes had the Caledonian Road been named thus, the true story is even more fortuitous:

Originally known as Chalk Road, its name was changed after the Royal Caledonian Asylum for the children of poor exiled Scots, was built in the area in 1828. The building has since been demolished and its site is occupied by local authority housing, the Caledonian Estate built 1900–7.[10]

For if Milo and his rather thinly described mates live on or near the ‘Cally’, the theme of the exile of Scots in London, as migrant victims of an Act of Union that worked, some would say if not O’Hagan (a Unionist last time I heard) to impoverish that nation, runs so much deeper, which is the fate of Scottish children, as an emblem perhaps of some of the issues of inequality between nations, classes and the power of hegemonic nations. But even if this is so, the theme of a childhood lost, together with its dreams is as important as the Scottish connection.

When he and his sister, Moira, still a Labour MP in Ayrshire, remember their common childhood. Moira cites Wordsworth not Burns (despite her status in Ayrshire), even though there is a lovely anthology of Burns’ airs by O’Hagan. For Campbell might share with Moira ‘a wealth of Glasgow patter and deep memories – “too deep for tears”’, but he visits that past not with joy but ‘straightforwardly terrified of ever returning to poor conditions’.[11] It would seem that Campbell does not with Wordsworth’s Ode: Intimations of Immortality … (which contains the phrase Moira remembers for them both,, “too deep for tears”) see guarantees of something splendid ‘in the grass’ and glorious in the remembered flowers of his childhood and youth, but rather something to be avoided, the memory of unrelieved poverty.

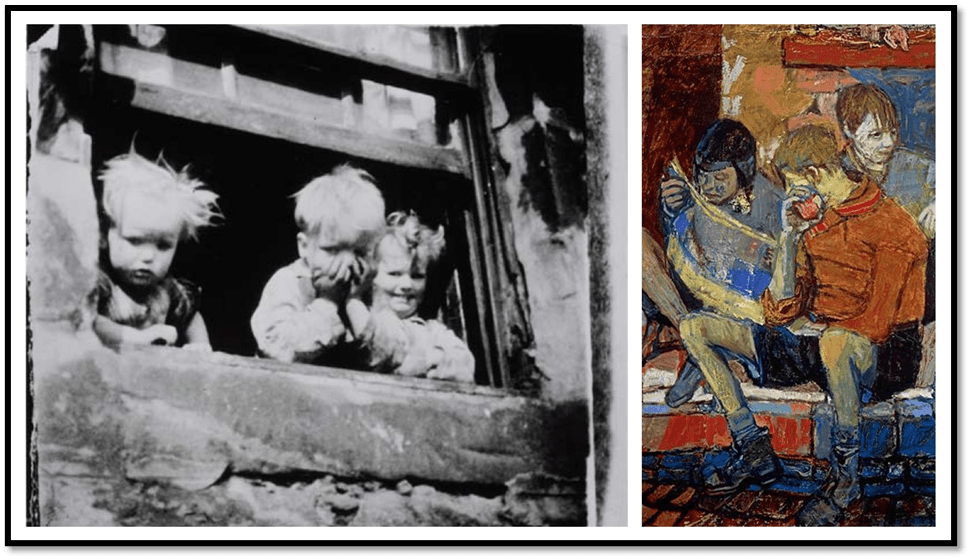

Yet Campbell, however terrified of the past, is also clearly haunted by it in a way that he will not let go, and transforms its associative imagery of the mind into a commodity, as he does all emotional material. He is the owner of Joan Eardley’s Boys Playing and hangs it over his fireplace in the sitting room of his resplendent Thornhill Square home (a place so off Caledonian Road, though near it, it is itself indexical of class difference (in the presence of a sitting tenant, Mrs Voyles, and in Milo’s visitations of it. I can find no painting though it is described in the novel as ‘what was now a notable painting’, called plainly Boys Playing, though ever so many like it in title and described content and offer the collage below as a taster for exploration.

A photograph taken by Joan Eardley of tenement children and her ‘Street Kids’, Joan Eardley, 1949 − © Estate of Joan Eardley. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2015. All from: https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/features/story-scottish-art-joan-eardley

The point is that painting triggers images of youth and anxious feelings of betrayal of his parents in the context of their working-class-based struggles, their hopes and their felt sense of betrayal. Moira too presumably saw ‘the damage in the children’s eyes’ that he sees in his memories and in Eardley’s capture of them: ‘The broken tenements, those faces’. But it has to left behind for him like his parents Alma and Jim: ‘a haunting sense that he had failed his mother and been worn down by her negative estimate, her belief that nothing in their lives had really worked out’. And just as he sees his parents in that light, it feels the same light reflected on him by his own children.[12] Youth really is a sullied thing, full of pitfalls.

All of this might stand behind the fortuitous placing of the novel on a Road named after a home for the poor children of exiled Scots. It is as if there is a haunting yearning based in a loss of home, origin and youth – the very thing Wordsworth got back when he looked at his childhood and youth, and why he wrote The Prelude. In the light of this, if we re-read a quotation I used earlier, we might see more viscerally how queerly deep in the psychology of the novel is Campell’s fascination for Milo Mangasha, not Scottish, but the essence of Caledonian Road and its links to being a magnet that colonial centres for the dispossessed to flee to its unwelcoming heart are. Such magnets are made by authorities to cow the nations and followers they have made subaltern to them:

Sometimes a young person can give the young person still alive in you a second chance. The boy was working class, like Campbell used to be; the young man wanted to act – and Campbell felt it keenly during the office hour, how a fresh association might replenish him and force him to embrace the change that frightened him.[13]

It is as if there is a haunting yearning based in a loss of home, origin and youth – the very thing Wordsworth got back when he looked at his childhood and youth, and why he wrote The Prelude. That Campbell re-enters his youth through layers of guilt at the circumstances in which it is left behind in his psyche and geographically through Milo, we can see in the lack of direction that thinking about Milo creates in him as ‘part of the thrill’ of falling in love, or something like it in its psychological content, with the imago of a younger man, recalling himself. Milo steals his passport to test the answer to his email question to Campbell: “Are you a good person?” It all occurs this replenishment and return to youth symbolically in the month of June, described as ‘a spring holiday from himself, this lively intensification of his friendship with Milo’.

At the moment this is happening, Campbell’s psychotherapist wife reflects thus about her husband:

He put her in mind of some of the children she had treated over the years, the patients troubled by a sense of unachievable selfhood. It occurred to her that he perhaps wanted to be several people at once, none of them much like him.[14]

Milo was always bound to fail him. People do unless you reinvent their story in your own mind and impose it on them as Bozydar’s, the criminal people-smuggler, mother does with one of her real son’s best-working Polish immigrant, Jakub, for whom she searches a wife, and helps him to get his brother from Poland, whilst knowing really deep down that he is gay and threat his brother is actually his desired long-term lover, just as she might with a son she could approve more than the villainous Bozydar. The relationships of mother and child, and father and boy child are the crux of this novel. This is why probably Andrew O’Hagan’s scoping article in The Guardian prior to the book’s publication was a study of how the concept of children leaving a parental home to make one of their own has changed, which contrasts how sons and daughters do the deed and how parents apparently, and really deal with that, even himself. The story of his mum clearing his room before he passed Carlisle (not that far from Ayrshire) reminded me of things. At the end of the novel, he tells of having spent 10 years writing Caledonian Road and that it is about ‘class, politics and money’. But he adds that also to him, it:

tells the story of a person who has left part of himself back in the Glasgow high-rise where he grew up. Perhaps that’s a story of society that we are always seeking to tell in new ways: how we stay progressive as the years pass, and how we might join the hopes of our past to the realities of the turbulent present.[15]

The hints that the psychological material goes deeper could not be clearer, although it is merely a fact that the theme of leaving or staying a home of origination and unfinished tasks is a common one. I have dealt with in blogs about novels by Jon Ranson, Andrew McMillan and Rupert Thomson in the past. And this is why I used the following quotation in my title (somewhat extended here:

… he knew he was a thinker in danger of becoming thoughtless. At fifty-two, he knew himself to a traitor to the class of his youth and a freak to his own moral understanding. You can’t live your life being celebrated for beautifully preaching what you will never practise, and this was the certainty that had begun Campbell’s trouble. He’d always written rather blithely about goodness, truth and harmony, but hadn’t he, in actual fact, travelled far from these things, and had he any choice now but to find a way back? [16]

That phrase at the end of my cited passage could be ‘find a road back’. It’s worth saying I think, because the road is Caledonian Road – a road where the themes of a Scotland of class deprivations and exile persists, especially those of children and especially – in this novel – boys. In novel’s by men lost paradises are paradises of men, and I think this is why so much of this novel concerns the perils of unexplored masculinity. Campbell has many avatars – corrupt women-baiting Tory Oxbridge friends as well as others but he feels ‘a stab of hurt’ when he sees Milo at a hairdresser’s ‘sitting in a shop window with a beautiful woman’ (it is Gosia his girlfriend and Bozydar’s brother). He calls Milo to break up her attentions on him for ‘it had never fully occurred to him that the young man might have worlds of his own’. After all the unanswered issue of the book is ‘Why Men Weep in Their Cars’, the name of a book on The Crisis of male identity in the Twenty-First century.

It is this issue that not only prompts his book, a book he will never own as his own, but makes sure his ‘past was available all of a sudden’, as he watches successful men enact roles they seem unable to ethically ore even practically sustain with high moral turpitude being involved: ‘All these men falling apart. Campbell didn’t quite feel himself to be one of them, not yet, but writing the little self-help book had unnerved him’.[17] It remains an unanswered question why he chooses Jake Hart-Davies to front his book, whose ‘central energy’ amongst peers doesn’t suggest the nuance Campbell puts into that role: ‘Jake Hart-Davies arrived with two male models. They spread among the group, lighting each other up, touring their phones’. Jake is empty: he confirms his presence with his absence, we are told – a clever phrase reminiscent of justifications of a supreme deity. [18] Later this difference between them is spelled out: ‘Jake Hart-Davies had a way of showing interest that Campbell found to be masterfully shallow: he offered a display of concentration, as opposed to concentration; … ‘. The beautiful fun of that characterisation is at the root of the same question asked throughout the novel however, and asked just at this point by Jake, talking about what he got from his father:

“… Vanity, like sexuality, like morality, like art, was a foreign concept that left him perplexed. Being a man was unforgivable, and he looked from the centre of his life like Rembrandt looks out from his final self-portrait, already sick and already condemned, observing in silence what he knows about the difficulties of being a man. …”. [19]

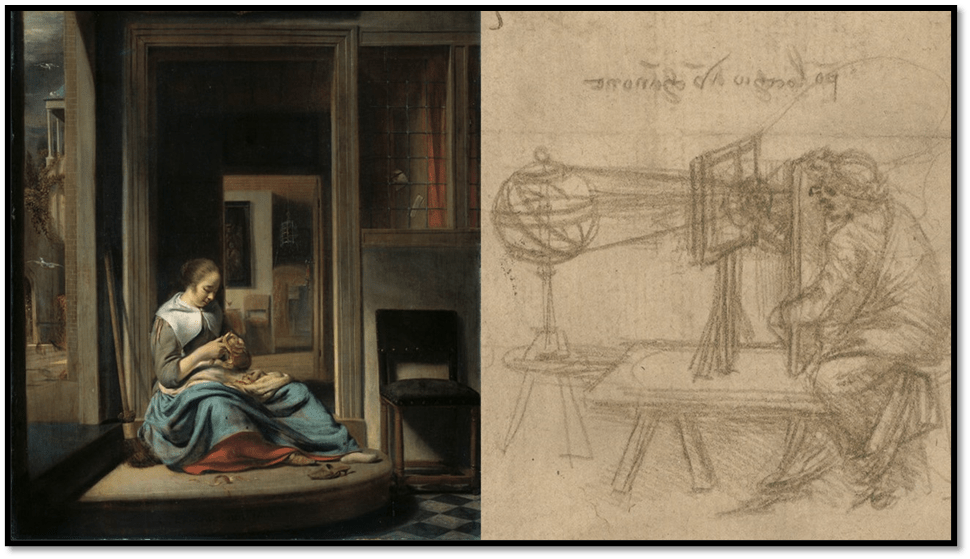

Twaddle! Indeed, but twaddle the book takes seriously like the ‘invisibility’ of a man like Vermeer in Campbell’s theoretical LIFE OF VERMEER.[20] O’Hagan surely quite reveres the dying Countess in the book, a power of the past, who says that ‘male pride’ is ‘the cause of everything that’s wrong with the world’. She may say ‘Poor dears’, but the Countess has our number.[21]

I suspect that O’Hagan believes that there is a problem with the ‘contrition’ of men for the problems they cause to women and each other, but perhaps especially their sons or son-substitutes. It is the same with all powerful groups who think they have the solution to disempowerment that the exercise of their own has caused in the marginalised other, as in his analysis of ‘white contrition’ in an essay he has written just as the novel opens. It is just that people keep reading him as if he was in favour of continued power for the already entitled, as Jake does in pretending to be its author without understanding its inner conflicted being. That conflicted being is contained I believe in what is supposed to be a direct quotation from Campbell Flynn’s Life of Vermeer:

We can’t know ourselves until we know people who aren’t us, the specifics of their existence. And that story will be the story of how we lived.

This is very like Flynn’s ‘crumpled’ goodbye note to Milo and plays the same games with the notion of self and alterity. If you like this is the game the novel tries to play. It tries to imagine the alterity of people labelled social problems. At its heart is Brexit, the pandemic, the inequalities that both involve, and most particularly in public stories of ‘small boats’ wherein no-one tries even to understand the lives that are contained in, and also lost from those boats. This is why I think the story of Jakub is dealt with such love and attention., even imagining his integration into the Leicester Railwaymen’s Club. This is the story Campbell should have inhabited and understood rather than the merely convenient Milo. Jakub is full of nuance about motive – so is Campbel and he should be honest about it – as in where, sometimes, Jakub ‘thought he was doing all this for his boyfriend, for what Robert wanted from life. He missed Robert’s warmth and the energy that came from him, and often during those weeks Jakub had the feeling of desperately wanting to go home’.[22]

There is a directness in Jakub that there isn’t in other characters who are not simply criminal in their motivation. For him, home and exile, warmth and cold loneliness are continually in contest to shape him – but though he takes energy from Robert he uses it to grow as a person, to accept the openness even of his relationship with Robert. What he learns he learns from people as marginalised as he, the oppressed Leicester women migrant workers. Yet: ‘They seemed to own themselves and their hardships appeared not to unsettle their unhappiness’. Jakub works as a good under-manager and is a good ‘union man’. Without Campbell’s (or Milo’s) whining, he is truly : ‘denationalised, trapped, but somehow determined to work on, to get to the better place in his mind’. His tragedy is one that helps us realise the terror of an event all of us read in newspapers. He is suffocated to death bringing Robert back to England with him in a freezer container that is overcrowded, the subject of a politics that has no care of him.

No doubt I fail to get anywhere with all of this. I both liked this novel and felt it somewhat over-schematic. Some things in it ring false but some things ring very true. It was hard for me to read I think for at crucial times in my life Caledonian Road was part of my life, I might write about that to exorcise it – but in another blog. I certainly enjoyed reading this novel and it is one that lovers of a story will do too. But Campbell Flynn is probably what it is all about. Nevertheless am no sure about that. Pentonville Prison, as an experimental Panopticon as a place of significant closure matters in Caledonian Road the novel and to anyone who has experienced traveling by any means including walking the Caledonian Road. It adds to the novel’s treatment of visibility, enclosure and their opposites. For me it’s still magical and a bit fearful – the Cally – the real road of which we speak.

People talk about it as a ‘state-of-the-nation’ and a pandemic novel, they find it situates us in its own London as well as, according to Suzie Mesure in the i newspaper anyway, ‘Dickens did for its Victorian counterpart’.[23] But in that lies its weakness in part. People keep trying out the novel that in Mesure’s terms, connects ‘the bottom of the society to the top’. But it does so with many characters failing to be other than the types they represent, as with the Veneerings in Dickens or Jo the crossing sweeper in Bleak House. Dickens did this on purpose but I wonder if such a strategy is open to the novel in a post-modern arena. It doesn’t work really when J.B. Priestley or Angus Wilson do it. O’Hagan is a better writer than the first and at least as good as Wilson. Mesure says the novel is a ‘car crash in slow motion’ and certainly the period it covers felt like that, but, at its best, it is Campbell Flynn’s ‘car crash’. It is the novel of the moral demise of a man from being to nothingness, from someone who having realised he has betrayed the politics and political-home values of his past, can do little else but betray the present and the future; at the end as throughout he is an invisible man: ‘nobody could really see him, but he was inside his perspective box, a place of illusions as well as facts’.[24]

Of course the perspective box was an instrument of the visual artist best used by Vermeer, as is well known, and its use was predicated on the belief that we best create things that look real based on things that offer us the profundity of artifice and grand illusions.

Much love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Andrew O’Hagan (2024a: 16) Caledonian Road London, Faber & Faber

[2] Ibid: 23.

[3] https://forebears.io/surnames/mangasha

[4] O’Hagan (2024a) op.cit.: 159

[5] Ibid: 457

[6] https://www.livescience.com/what-is-singularity

[7] O’Hagan (2024a) op.cit: 26

[8] Ibid: 25

[9] I need to come clean that the Caledonian Road from King’s Cross to Northern London (in my case Holloway and Finsbury Park in one direction away from its upper end) and to the area around Sadler’s Wells theatre (in the other direction) haunts me at the moment. I do not think this determines the reading but I will write that personal reference out in a later blog to exorcise it. If and/or when I do so, I will create a link to it over these very words.

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caledonian_Road,_London

[11] O’Hagan (2024a) op.cit: 17

[12] Ibid: 36f.

[13] Ibid: 25

[14] Ibid: 155

[15] Andrew O’Hagan (2024b: 51) Dreams of Leaving in The Guardian (supplement) (30.03.24). 49 – 51.

[16] O’Hagan 2024a: op.cit 16

[17] Ibid: 75

[18] Ibid: 134

[19] Ibid: 238f.

[20] Ibid: 292

[21] Ibid: 268

[22] Ibid: 185

[23] Suzie Mesure (2024: 48) ‘Dickensian panorama of London today’ in the i newspaper (Friday 22 March 2024): 48.

[24] O’Hagan (2024a) op.cit: 641