Speaking the Unspeakable: Alphonse Daudet ‘In the Land of Pain’

In the Land of Pain’ was Barnes’ own chosen title for this book and is his translation of a phrase Daudet invents in the book to describe a sanatorium for the dying. Let’s face it: Julian Barnes’s edition of his own translation of La Doulou (La Douleur) – the title translates as simply Pain, either from the Provencal or standard French in the original – by Alphonse Daudet is a book that you cannot imagine ever being published, yet it is (by Jonathan Cape), or having an audience keenly waiting to read it. ‘ Daudet invents a dialogue between two sufferers of ataxia at the end of the book that imagines the context of a book better never written (let alone translated with scholarly notes) than written, as it really was – though never publish by the writer in his lifetime. The ‘First ataxic’ (clearly Daudet himself says to the second who takes him to task for perhaps suggesting that ‘when someone’s in pain they don’t have the right to mention it!’:

But I’m in pain too, at this very moment. it’s just that I’ve trained myself to keep my suffering to myself. When the pain gets so bad that I have to give vent to it, you should see the fuss it causes! “What’s the matter? Where does it hurt?” I have to admit that “what’s the matter” is always the same, and that they’d be perfectly justified in replying, “Oh, if that’s all it is.” Our pain is always new to us, but becomes quite familiar to those around us,. It soon wears out its welcome, even for those who love us most. …. No, the only real way to be ill is to be by yourself.

All this is very ironic, of course, and Daudet treats the First Ataxic thus, as he goes to ‘cite’, to the Second Ataxic, ‘all the anguish he has to keep to himself’.[1] The only way to keep something to oneself, it seems, is to find someone to share the thing you are ‘keeping to yourself’ with. Even that can raise a laugh double bind of speaking of the unspeakable can be made strangely, and perhaps even humorously, ironic in writing. Barnes goes to great trouble to show how complex it was for Daudet to find a form in which to share what everyone thought it was wrong to share about himself. Indeed the book, made up only of ‘notes’ never edited by the author into a public form is itself continually repeating itself, never advancing really in understanding or even greater comprehensibility. For instance the First Ataxic’s speech is often a repetition of Daudet’s earlier note, such as this: ‘Pain is always new to the sufferer, but loses its originality for those around him. Everyone will get used to it but me’.[2]

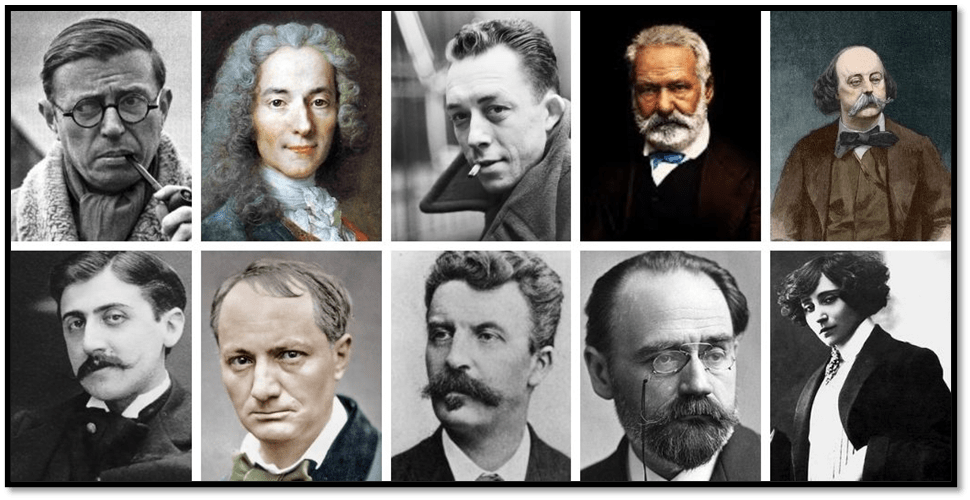

But silence on the part of sufferers is not only because one might bore others with no incentive to hear again what to the sufferer is new each time in suffering. It is also because one fears revealing the cause of the suffering – the ‘true ‘matter’ as it were. Daudet both wanted and did not want to share his interest in the way his syphilis, then incurable, progressed through its manifestations of individuated decline in its tertiary stages in particular. Sometimes this was in protection of his reputation as a jovial novelist, favoured by Charles Dickens, as Barnes tells us, as his ‘little brother in France’ (writers always loved him but could never refrain from pointing out his small stature 9he was a ‘great little novelist’ to Henry James and ‘mon petit Daudet’ to Edmond de Goncourt (also a sufferer of syphilis), his closest literary friend). Even as a literary ‘syphilitic’, Barnes reminds us, he was overshadowed by the ‘Big Three’: Baudelaire, Flaubert and Maupassant.[3]

Daudet, at one moment, imagines himself as the very same small, almost insignificant, animal, shy and with nothing to say – the perfect emblem of the private and reclusive gentleman even in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind In The Willows, a mole: ‘I’d live to be earthed in like a mole, and live alone, all alone’.[4]

Cut from illustrator Brian Lies available at: https://cricketmedia.com/blog/5-free-stories-and-poems-for-the-winter-holidays/

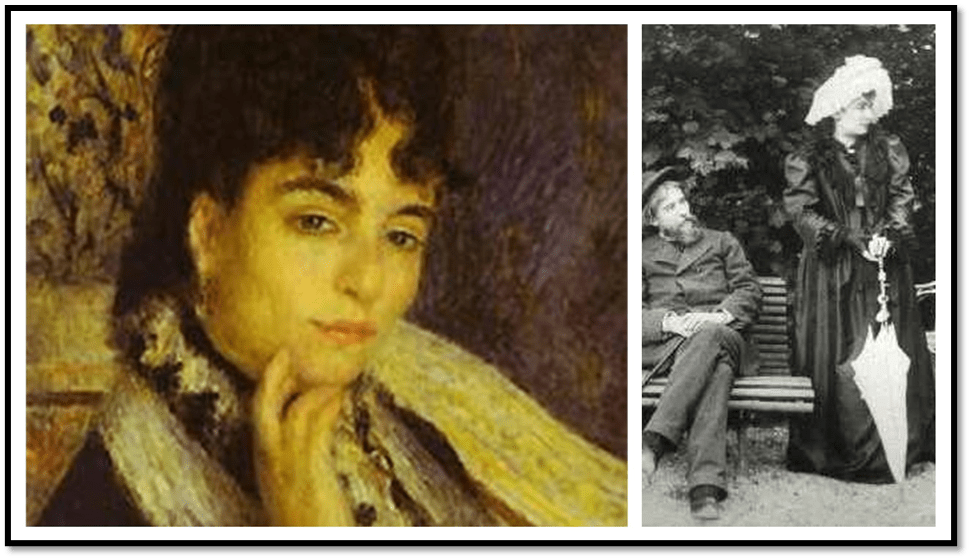

Barnes makes much of Daudet’s sensitivity to Julia Daudet, his wife, aware of being ‘a terrible weight on a household, …, someone whose illness drags on for years and years’. As the First Ataxist however, he represents wives and children as to be cared both for and about, certainly, but as something he would be luckier to be without so that he can be ‘allowed to suffer without embarrassment or constraint’.

Detail of Julia from Renoir painting and Daudet with Julia.

However, think again about the word ‘constraint’ in the vignette above. I what but Daudet himself rather finds amusements at times in the strategies of wives at higher class sanatoria to ‘silence’ their husbands, as in this economic vignette of the Lamalou-les-Bains sanatorium:

Only at Lamalou have I seen wives keeping such a close watch on their husbands, preventing people from talking to them, so they can’t discover anything about their illness.[5]

Daudet looks for the funny throughout, and I think he finds this funny, though Julia Daudet may not have done. But a husband under surveillance matches other images of constraint for Daudet. At most times silence about syphilis, rather than its symptoms, such as ataxia, is at the behest or in deference to the imagined sensitivity to others, particularly the wives of sufferers, for instance as we saw above. It is a sensitivity though felt as pain as so extreme its display is that of the prisoner in a Gothic prison, perhaps underground like the Count of Monte Cristo, that has advantages, nevertheless, to the enforced silent, for you are protected from your own need to share your pain:

Part one: locked in.

Wanted a prison so that I could shout: that’s where I am.[6]

These short emblems are so full of ambiguity. After all, you don’t think when you discover yourself imprisoned to have been put there yourself, however desirable the image of being free to shout for the first time is. It’ is a perfect emblem of the double-bind. I want to speak to you about my pain. I cannot speak to you about my pain lest you hear me and suffer yourself. But being ‘locked in’: do I deserve that?

And the whole book has this kind of ambiguity, if not, more truly, multiplicity. The big question for Daudet is to ask whether pain has any consolations. Sometimes he thinks it has and asserts it in a note:

Pain, you must be everything to me. Let me find in you all those foreign lands you will not let me visit. Be my philosophy, be my science.

Yet, within another axiom he loses his assertion, already ambiguous as it is with its accusation that if pain is the answer, it is an answer to a problem it creates. Now:

Pain leads to moral and intellectual growth. But only up to a certain point.[7]

The whole book is built on this issue. It starts with a triple-rhyming motto in Greek (Mathimata – Pathimata) , which Barnes glosses as ‘Suffering is instructive’:

Μαθήματα – Παθήματα

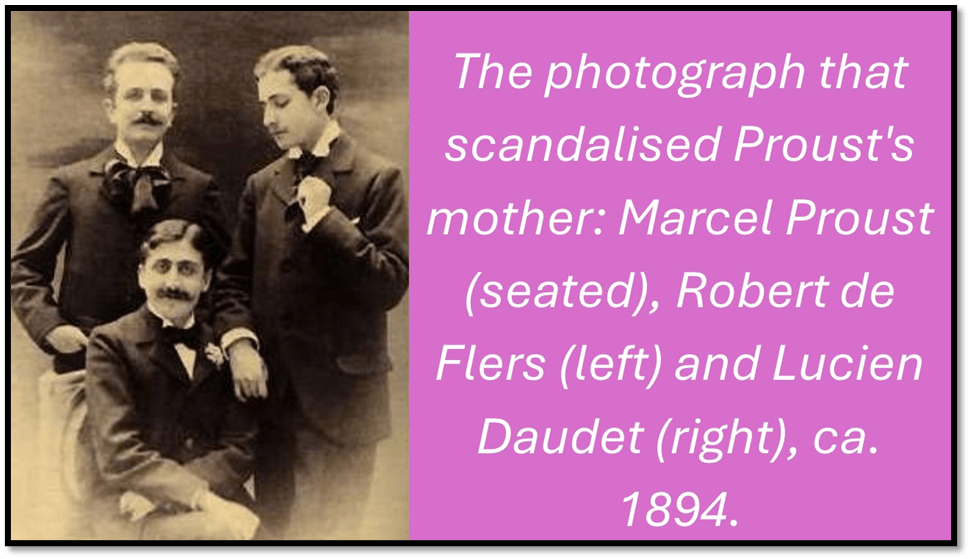

‘But only to a certain point’, must be the rejoinder to whether pain instructive or not, though Daudet only shows this lesson in reductive moderation of a statement at the beginning of La Doulou by the irony of illustrating that, when the writer is asked (hoping presumably for the name of some upcoming work by a great author), Daudet can only answer: ‘I’m in pain’.[8] This answer must rather underwhelm the listener, even though IT IS THE NAME OF THIS WORK, forced now, as the listener is, to seek to display some sympathy or empathy of neither of which they feel that deeply. Even Proust, Barnes tells us in a brilliant footnote, felt he could not look Daudet ‘in the eye’ for it made him think how debilitated was he compared to Daudet when his (Proust’s) pain was – in his translated words From Contre Sainte-Beuve – ‘so slight compared to his’. These words must amaze any reader of Proust.[9] Although it is worth remembering that Daudet’s younger son, Lucien, was one of Proust’s lover for a time.

Of course for both writers the experience of time is important factor too but there is no return’ of ‘lost time’ in Daudet, only the inexorable passage through the sub-stages of tertiary syphilis, individual as he keeps on reminding us, for everyone. Sometimes those of others have to remain unknown to him, such as the ‘mysteries of female illness; clitoral maladies’. He meets Major B— just before this at Lamalou, whose third-stage induced blindness varies, and sometimes ‘Everything’s black ….quite black …’. At other times memory gives a lightness which is a ‘break in the clouds’. Daudet is not blind – it is not one of his symptoms, but he too says:

… ‘Everything’s black ….quite black …’. This is the colour of my whole life nowadays.

Pain blots out the horizon, fills everything.

I’ve passed the stage where illness brings and advantage, or helps you to understand things: also the stage where it sours your life, puts a harshness in your voice, makes every cog-wheel shriek.

Now, there’s only a hard stagnant, painful torpor, and an indifference to everything. Nada! … Nada! …[10]

Had this passage of brief notes been the most glowing of Proustian periodic sentences could it have been better. Gaps and omissions speak Julian Barnes tells us:

Notes seem an appropriate way in which to deal with your dying. They imply the time, and the suffering, which elapses between each being made: here in a decade or so of torment reduced to fifty pages.[11]

Are notes then a strategy to speak of the unspeakable to the unlistening (perhaps) by leaving some of it to the gaps between sentences, paragraphs and sometime simple single words. That silent communication is often that that speaks to those who already know one’s pain. There is still a problem here because there is the stark title-like note says: ‘There is no general theory of pain’. He continues:

Each patient discovers his own, and the nature of pain varies, like a singer’s voice, according to the acoustics of the hall.

It is an interesting metaphor that in the last quotation – individuality is merely a different ‘hall’ the same singer – pain – sings in. You couldn’t have a more depersonalised take on pain. And yet, as the syphilitic symptoms progress – involving for him involuntary movement or catatonic and physical freezing of the limbs in total lockdown, Daudet still looks out for the perfect interlocutor to HEAR him by feeling it in his body too (I say his because the examples are all men I think). He calls these his doppelgangers (the French term ‘sosie’ can be used in the supernatural and clinical uses too) or ‘doubles’. Even these lookalikes actually differ, like the first and second ataxic for both are versions of Daudet I suppose – the lonely man locked into being showy about his pain, the family one dependent on having his other self (the second ataxic) if he is not to die in very profound silence.

At Lamalou, it is hard to know who watches whom most and for what benefit:

The man who watches the others suffer.

The doppelgangers.[12]

Do these doppelgangers suffer FOR you, in brief ? Are they the objectified and projected form of one’s own pain? Are they continually being introjected as if they were these things? Sometimes you watch for analogies and similarities ‘between all illnesses: eyes either feverish or lifeless’. Sometimes their diversity is in fact the reason they are all alike in being different right down to the “Napoleon Who Never Made it”.. What a paradox!.[13] At one point he describes ‘him’, the so desired ‘doppelganger’ though it is obvious there is more than one of him however specified the singularity of the description:

My doppelganger. The fellow whose illness most closely resembles your own. How you love him, and how you make him tell you everything! I’ve got two such, an Italian painter and a member of the Court of Appeal. Between them, these two comprise my suffering.[14]

None of this adds up – this game of likeness and difference – for Daudet in the end. He is always at least two things not one, and most likely many more than two. As a writer elsewhere he seeks his ‘doppelgangers in pain’ amongst near-peers, like Baudelaire and Flaubert. Their obsessions and struggles he thinks ar the same as his, though that is a large claim for even a great ‘little novelist’. He looks too for literary forebears such as Leopardi, even pressganging into the herd ‘Pascal’s neurosis’. The latter is an act, according to Barnes’ footnote, ‘to attempt to enlist as a fellow-sufferer avant la lettre (as syphilitic he means before the term has been used). Similarly of other greats:

Heinrich Heine is much on my mind. I feel his illness was similar to mine.

I wonder if I shouldn’t add Jean-Jaques to my list of ancestral dopplegangers in pain. Wasn’t his bladder-disease. As it often may be, a warning sign and side-effect of ‘disease of the marrow’.

Of those here only Heine did have syphilis, Barnes tells us. The rest are imagined to have it by Daudet from symptoms from wide-ranging bodily complaints. To pressgang Rousseau however, the great Confessor, was probably a necessity for a writer alarmed at how much he may say and how much he must hide behind masking synonyms for what he sometimes calls ‘pox’. La Dolour will never be Les Confessions. In the French I wonder if this comes across more strongly – the degree to which Daudet’s ‘dis-ease’ is a lack of ease about what kind of writer he can aspire to be:

For instance, the following is in the French text:

Nervoisisme. Impossible d’ecrire une envelope que je sais vue, regardée de tous, et je peux guider ma plume à mon gré dans l’initmité d’un carnet de notes.

Modification de l’ecriture…

Cette nuit, la douleur en petit oisea-pück sautillant ici, là, poursuivipar la piqûre; …

In Barnes’ English, this is:

Neuropathy. I find it impossible to write an address on an envelope when I know that people will read and examine it: whereas in the intimacy of a notebook I can guide my pen as I choose.

The change in my handwriting …

Tonight, pain in the form of an impish little bird hopping hither and thither, pursued by the stab of my needle; ….

It is not just that ‘la piqûre’ can be the bite or sting the bird’s beak gives as well as an injecting needle – its primary meaning for the context of course – but that ‘Nervoisisme’ can be a non-medicalised nervousness as well as a more psychiatric term ‘neurosis’ (for just because Charcot appears in the text, the great psychiatric neurologist, we do not have to medicalise with him) and ‘l’ecriture’ can have a much wider reference to the desired ends of writing and not just refer to ‘handwriting’, though again the primary contextual meaning. ‘Modification‘ might involve a lot more changes – of content style and other editing than the English simple reference to the way Daudet’s handwriting is no longer clear. To form ‘L’ecriture’ of a significant kind is the aim of French great writers and that involves a lot of ‘Modification‘ .

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Alphonse Daudet (trans. & Ed. Julian Barnes) [2002: 76f.] In the Land of Pain London, Jonathan Cape.

[2] Ibid: 19

[3] Ibid: vi f.

[4] Ibid: 42

[5] Ibid: 66f.

[6] Ibid: 44

[7] Ibid: 42f.

[8] Ibid: 3

[9] Ibid: 15 (f.n. *)

[10] Ibid: 64f.

[11] Ibid: xiv

[12] Ibid: 67

[13] Ibid: 60f.

[14] Ibid: 61