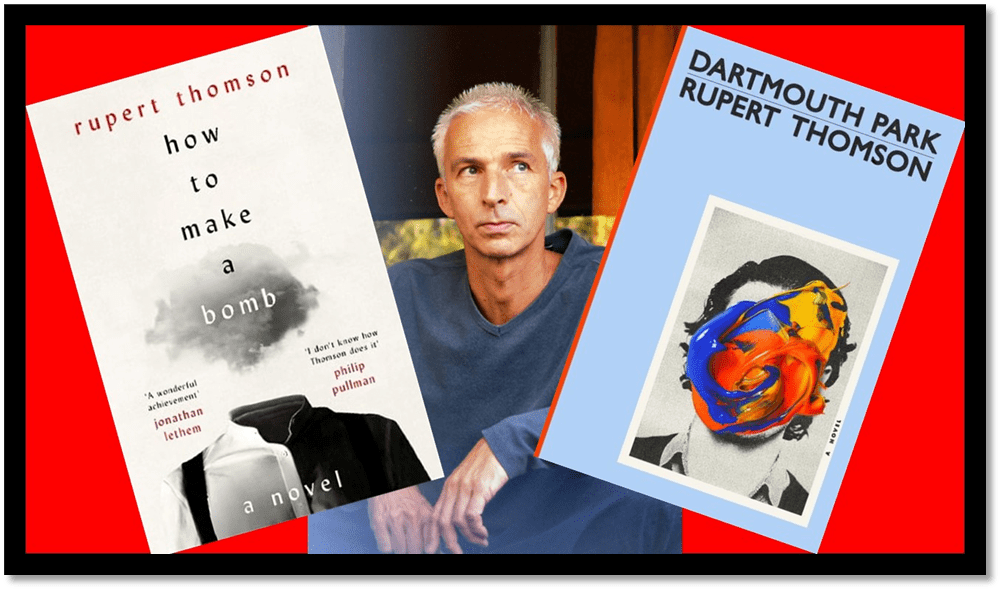

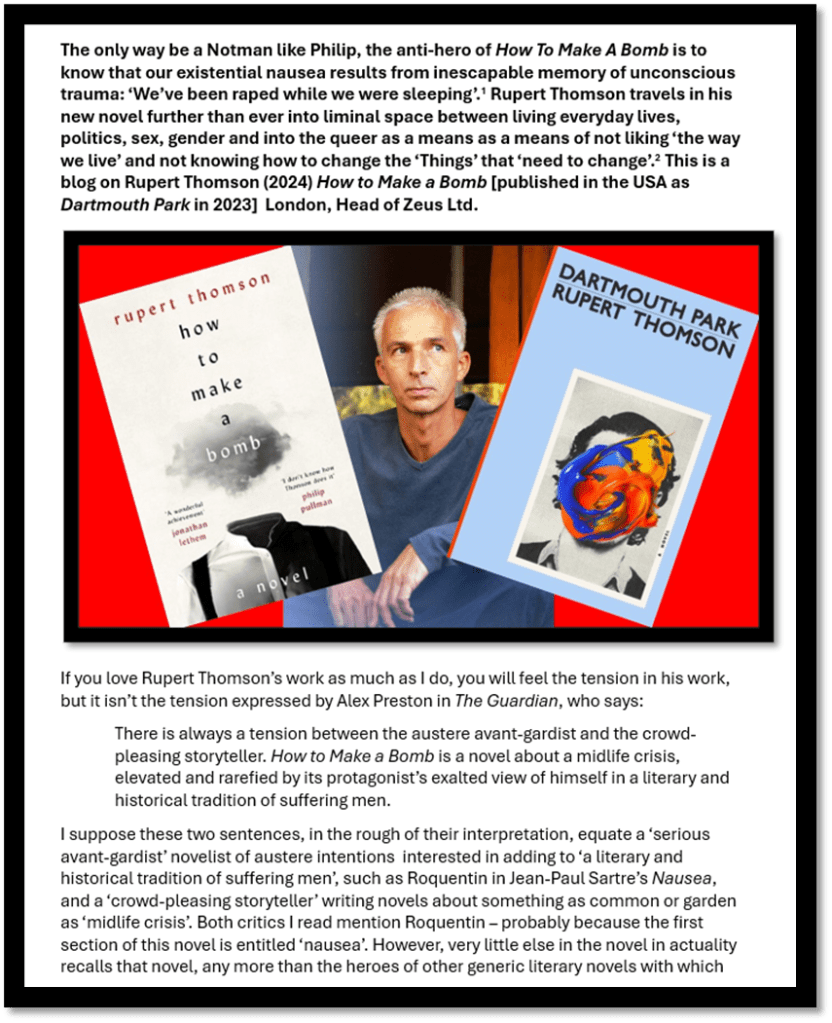

The only way be a Notman like Philip, the anti-hero of How To Make A Bomb, is to mistake inescapable memory of unconscious trauma for existential nausea and make it the basis for a political ‘notmanifesto’. Yet it may still be necessary to face the feeling that: ‘We’ve been raped while we were sleeping’.[1] Rupert Thomson travels in his new novel further than ever into liminal space between living everyday lives, politics, and forms of binary sex/gender on the one hand and the queer on the other as a means as a means of not liking ‘the way we live’ and not knowing how to change the ‘Things’ that ‘need to change’.[2] This is a blog on Rupert Thomson (2024) How to Make a Bomb [published in the USA as Dartmouth Park in 2023] London, Head of Zeus Ltd.

If you love Rupert Thomson’s work as much as I do, you will feel the tension in his work, but it isn’t the tension expressed by Alex Preston in The Guardian, who says:

There is always a tension between the austere avant-gardist and the crowd-pleasing storyteller. How to Make a Bomb is a novel about a midlife crisis, elevated and rarefied by its protagonist’s exalted view of himself in a literary and historical tradition of suffering men.[3]

I suppose these two sentences, in the rough of their interpretation, equate a ‘serious avant-gardist’ novelist of austere intentions interested in adding to ‘a literary and historical tradition of suffering men’, such as Roquentin in Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea, and a ‘crowd-pleasing storyteller’ writing novels about something as common or garden as ‘midlife crisis’. Both critics I read mention Sartre’s Roquentin – probably because the first section of this novel is entitled ‘nausea’ and in it, like Roquentin Notman fears the inauthenticity of a world transformed into commodity values not real ones and tries unsuccessfully to cure it by an affair of sorts with a new woman in his life. Preston says that Notman’s condition, so often referenced in the novel, depends on our knowing that in, ‘Jean-Paul Sartre’s first novel, Nausea, the protagonist, Roquentin, suffers a strange “sweet sickness” that is the physical manifestation of a deep existential malaise ‘.[4] Another critic, Caleb Klaces, says more insistently, as if the subject suggested to his putative students for a dull Ph. D thesis, ‘is, at one level, a satire of existentialism, suggesting that Nausea may be an unconscious elegy for the fantasy of white male omnipotence, masquerading as philosophy’.[5]

However, very little else in the novel in actuality recalls that novel any more than many others. It rather spills into different genres and mimics different heroes of other literary-mythical sources. Caleb Klaces certainly makes that point when he says that:

Skewering ‘Sartre’s earnest example, Thomson’s novel turns metaphysical inquiry into a picaresque. Notman has already tried, and failed, to find something “authentic” in infidelity and folk tradition’, but he could have followed those examples up more pertinently.[6]

That is because the woman with whom he tries out a relationship that fails to be as chaste as that aspired towards is with a woman named Inés (a Spanish name that has variants in other languages including Agnes in English) meaning ‘chaste’, pure’ or virginal, who, as it were plays the role of the Lady of a courtly romance, if rather a Dulcinella in the event. She compares Notman to the progenitor of all picaresque heroes, Don Quixote, allowing him to bear the various meanings that are read as the interpretation of that mock-knight’s quests throughout the history of its European critical reception. In a kind of summary of that reception, reflecting Inés’ academic tone as a lecturer at the University of Cádiz, and thence suggesting something rather pedestrian about her.

It is not, in passing I should say, that she is unlike Notman as an academic himself when he exerts himself on his subjects and especially the little-known historian, Priscus of Panion, whose accounts of Attila the Hun, Notman can use in ways where he seems to compare himself to Attila. For instance, as he plans a target for an attempt at political terror on a City Tour bus in London, he implicitly compares himself to Atilla in Priscus’ description of the Huns following a deer into Scythia that shows there is a means of access into what he thought ‘impassable’ natural defences, ripe now for Hun conquest.[7]

However, whilst Philip merely thinks all this inwardly, Inés speaks of , in what feels like the tones of a dull lecture to other people (hardly appropriate we might think in a social conversation with a new potential lover however ‘academic’ the context of their first meeting) to Notman about, pedantically giving the book its full title, The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha. The comparison is given because this is literary hero of which, since he sought her out in Spain, Notman had reminded her :

In the decades after the book was published, people thought of Don Quixote as a self-deluded fool.

Later, in the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth, literary opinion shifted, and he was seen as more heroic, someone who was battling against a mundane and prosaic existence.

…

More recently, she said, he seems to represent a quest for personal identity.[8]

It is not clear that Philip knows what to do with these rather pedestrian, in the world of an academic at least, multiple possible interpretations of his potential meaning as an actor in his own story. Following her ambiguous leads and hints, from their first meeting, has been his way, though the direction of travel remains ambiguous. On first meeting in an academic conference in Bergen, Norway, he tries to describe the ‘way she looked at him’:

There was nothing in it that could be taken as evidence of anything.

It was like a text that refused to restrict interpretation.[9]

It is not made clear here though, that this text had any possible name (in fact they are Legion) but, even without specificity in its reference, her gaze upon him ‘felt like it meant ‘a lot’. Expanded on in Spain as a scholar’s take on Don Quixote, Notman must have felt somewhat over-categorised. But at least it is better than some identities he compares to his own later, like that of the narcissistic mass-murderer Anders Breivik.[10]

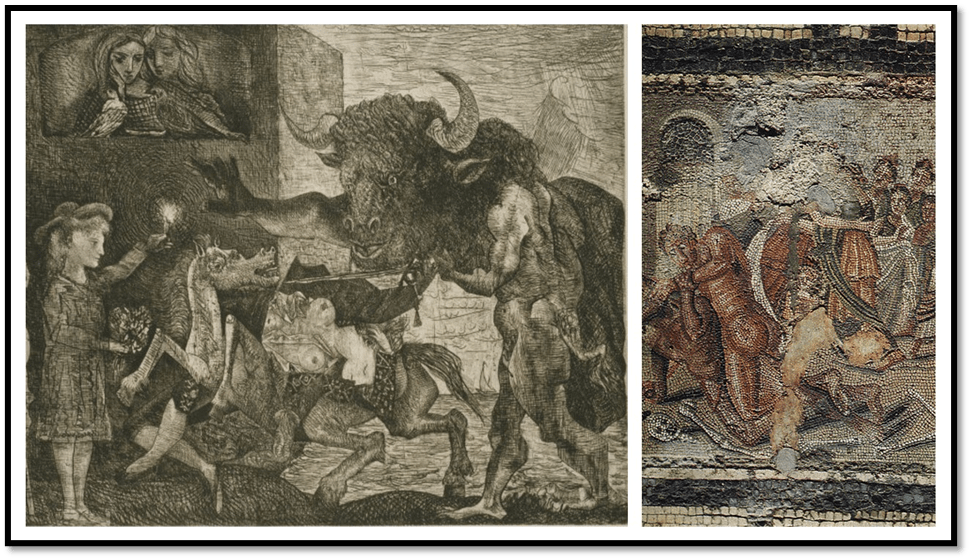

His most potent of identities however is that of Theseus that is posited supposed by the section of the novel called ‘In the land of the minotaur’ about Crete, using the name given it by Kristen, an older woman he meets in Piraeus[11]. It is an identity that places him as master of all kinds of labyrinth. It becomes the centre of his Notmanifesto quoted later in the novel (a manifesto based on a name and perhaps an ontological status):

Sickness, medication, pollution, sickness

We have created a vicious circle in which we have agreed to live

Our own poisoned labyrinth.

He even dares to think of himself directly as Theseus, although one with deficits in the planning of his goals or the means to achieve them:

Kristen had called Crete “the land of the minotaur”

What if he was some kind of Theseus – a Theseus who hadn’t thought to bring an Ariadne, a Theseus with no sword, no thread?[12]

Without the tools traditionally held by man or woman, Theseus is somewhat lost, and, for me this underlies the meaning of Notman as a being on the cusp of sex/gender. Whilst not however ever tempted to either love or have sex with men, his anxieties (at least consciously for the attraction to Niko is ambiguous in its violence) propel him into exploring the realm of being NOT-MAN (or NO-MAN as his name is spelled in the hotel at Piraeus), into illusions of seeing men in half-dreams dressed as armed Cretan monks, ‘in black robes and a black kalimavkion with a veil’. A kalimavkion, by the way is very like the porkpie hat worn by the rebel-singer in Spain, though described as a stove pipe. The man has a ‘full, dark beard and wears his ‘rifle at an angle’ and poses a problem to Philip Notman of the meaning of male identity.[13] Similarly, as the novel progresses men become his standard, or his scaffolding, including the rather shady Ross James of RJ SCAFFOLDING (‘You said to contact you if I needed scaffolding’).[14]

In Crete, as Klaces says: ‘his search leads him to try homosocial company (the men of the local taverna are not forthcoming)’.[15] But Klaces seems to miss, as Notman does not, that these men do include him (or he imagines that they do) in their own taciturn way, just as too there is a kind of communion set up with his new neighbour Niko and his wife, a relationship based on aggression and a kind of queer male bonding. But in that kafenion: ‘He sat with the men at dusk and drank / He didn’t speak’).[16] Amongst these homosocial settings Notman feels he can, just by spending ‘a small part of the day with those men’ learn ‘something that he used to know, but had been deprived of’, and this thing he believes to a connection between self, community and environment.[17] Likewise in the Moni Preveli, a real monastery which I visit too, when Notman pre-imagines his acceptance there, a vision given short shrift in reality, he sees in a homosocial communion. He imagines talking to the aboot who in imagination will welcome him in because he convinces him of the meanings they share :

That was my feeling

And that feeling came from here:

He would gesture at a room, but his gesture would pass

beyond the walls to include all the building and all the men

who lived and worshipped there[18] (my italics)

It is all, I think, about males who provide a homosocial but also extensive male-inclusive communion, that they defend with male tools – with guns and silence. Men can share anything with other such men, even their regression to wetting the bed, as a boy does. He tells the abbot in his imaginary plea of this bed-wetting – but even Niko had been in on the secret of that ‘accident’ and had not shunned him for it.

I am the more sure that these homosocial groupings remain important as a definition of a shared manhood in a small detail that Notman notices as he quotes his notmanifesto to himself in a Travelodge hotel in Vauxhall. That is because the isolated line, ‘Outside, a group of men were chanting’, cannot but recall the function of the Preveli monks, even when that line runs on into another line, shifting, at the same time, the homosocial context to something more decidedly British. ‘It was someone’s birthday, or else a football team had won’.[19]

Even when Notman does an act of great charity and houses a homeless young woman, whose name is not accidentally Mary, in an inn (well actually the Travelodge) he finds her in a tunnel and decides on action as he observes around him on its wall ‘the tattered flyer for a gay club’. And sees her ‘dispirited by his lack of direction’. For men are meant to rescue you aren’t they?[20] Obviously it is difficult to not notice too that the nausea of a Notman or a Noman cannot merely be modern malaise in a novel with such a wide range of geohistorical reference, it is about a malaise that Notman too often constructs as about sex/gender in order to understand it. His reference points are from women: Jess, Inés, Kirsten, Mary and all of them try to teach him a new way of being a man, although none of them need him actually to rescue them, just to observe that he is in a labyrinth of his own making. Inés points him to mount the Torre Tavira of Cádiz and see it differently. What he sees is a labyrinth, just as Kirsten will point him to the same and Mary will be found in one.

Cádiz from high up

The flat rooftops …. Formed a maze of interlocking rectangles and squares, the streets between them only visible as straight, dark gashes

It is a ‘a puzzle that could be solved, but nothing came to him’. [21] If women set puzzles it is for men to solve them by healing their own malaise, but this all sounds suspiciously as if Klaces is right to see the novel as a kind of ‘unconscious elegy for the fantasy of white male omnipotence’ but not as philosophy as if only satirising Sartre’s Nausea mattered in the background of this book but the necessity to queer masculinity – to eradicate it from the binaries that sustain both it and a version of womanhood as victim, and victim alone, someone threatened by men but dependent on them for rescue. That surely is the dilemma Notman has to solve with his wife, Anya. Where Inés is left behind is where Notman discovers a mission in a ‘deep song’ that is, like flamenco, ‘rooted in oppression’. He doesn’t know yet that he is part of the oppression revealed by his malaise. My favourite literary reference is to a medieval morality play, when Philip realises his own allegorical potential, the role of Everyman in the play:

… he was an ordinary person

He was Everman

He was Notman.

If a modern Everyman is a ‘not-man’, that is because he realises, and internalises as his condition of being that the ‘roots of oppression’ lie in capitalist patriarchy and the binaries it spawns. Just before he speaks the words above comes the quotation I use in my title, but here at greater length speaking of the oppressive malaise that is the nausea afflicting us all:

It is as if we’ve been unconscious for a hundred years, like the princess in “Sleeping Beauty”

Not the Disney version, but the source of the Disney version. “Sun, Moon and Talia,” which was written by the poet and fairytale collector Giambattista Basile

In the original story, Talia was raped by the king while she was asleep

That’s what has happened to us

We’ve been taken advantage of

‘We’ve been raped while we were sleeping’.[22]

What he tells us of Sleeping Beauty is true. Giambattista Basile is a real figure from literary history and the story Sun, Moon, and Talia exists and includes that rape.

Male rescue has always been a myth and Basile told us this a long time ago. The sleeper is rescued but only to be subjected again to enchantment. And, if we were awake, we would remember too that Inés too is more or less raped in her sleep as he lies there ‘hard’ when ‘she drifted off before he did’: ‘I don’t want anything from you, he had told her / His body had contradicted him’. [23]

Like the Anders Breivik, that he really is assimilated with in some ways, as a terrorist he aims in reality to rescue no-one not even himself. The resolution of the novel cannot be in anything that Notman does – return to Anya or complete the triggering of his bomb: it lies in the fact I think that ‘Everyman’ is ‘Notman’ if he takes his name seriously and allows for the deconstruction of myth. I cannot see Thomson agreeing with me about that. But I do think he is aware that there are worse ways of categorising him. He has long been aware of the difficulties the literary establishment has with him. In this book, he plays with the many literary models I mention above (and there are more – not only literary, like the visual artist Edward Hopper and the musician Gustave Mahler).[24] Interviewed by Nicholas Wroe in 2013 for The Guardian, he listed all the authors he has been admiringly compared with:

“There’s Kafka and JG Ballard. And Gabriel García Márquez, Mervyn Peake, Charles Dickens and Elmore Leonard. I’ve also been called the male Angela Carter and the English Paul Auster. I’ve even been compared to Grace Jones.” And it doesn’t end there. The most cursory internet search soon reveals comparisons between Thomson and Orwell, Huxley, Chandler, Swift, Greene, Oliver Sacks, Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese.

But these comparisons are off-target he hints, Even in 2013 when other novels were yet to write before the one I look at now, he felt ‘of the inevitable comparisons to other writers’ that those novels would prompt: “People have always tried to put me in a box. But I think in the end, I just don’t fit”.[25] And that I think applies to How to Make A Bomb. It plays within itself with possible boxed categories to meta-describe itself: the novel of existential crisis, the domestic novel of male nervous collapse, the Everyman-like allegory of ‘how to live’, the novel of continual ‘dreams of leaving’ (the name of his first novel). He jokes about all this, saying, near the end when so many potential endings have been left behind as he leaves again or dreams (for these are important) of leaving, that his story could be easily changed to one with a quite polarised agenda: the nostos narrative honoured in Homer’s The Odyssey, and many a Greek drama including every part of The Oresteia: ‘his unexpected appearance at the house could be transformed into a homecoming’.

“I think in the end, I just don’t fit”, Thomson said in 2013 and if this novel is read aright, I think it boasts too that it is a very queer not-novel that doesn’t seem as if it wants to be anything definite but beautiful and complex. It is always making claims to be potentially any kind of novel but in the end it is what it is: art of a very high order indeed. The base of that art is still too, as he said in 2013, “an interest in damage and recovery” – damage and recovery that is psychological, social and somatic. None of this is possible to address until we realise old models don’t fit our needs. These novels of his queer every moment of life, refuse normative solutions or categories but they are nearer universal than we think. He said in 2013:

“But in that sense the books are universal. Part of being alive is about how you come to terms with the things that happen to you. So even though my books can be seen as strange or slightly otherworldly, these are things that everybody has to deal with.”

This is how Thomson’s stylistic innovations work, too, perhaps. Both Preston and Klaces admire the innovative style of writing, whilst insisting it becomes normalised to a reader. Preston says it is ‘written in an unusual kind of free verse with line breaks replacing full stops, although, as with any successful stylistic effect, you stop noticing it after a page or two’. Klaces goes ignores the look of verse and concentrates on punctuation, saying it is writing:

without a single full stop or quotation mark. Instead of conventional punctuation, each new sentence begins on a new line. Both stark and slick, it’s a surprisingly unobtrusive subversion of prose form.

Neither description suits me for I never stopped noticing the varieties with which line lengths and sense breaks were engineered often not only with skill but with effects that raise both the strangeness and beauty of the achieved meanings. It sometimes looks like Whitman’s verse but never sounds like it. It has effects of its own. Take this conversation with a taxi driver in Cádiz where the sense of what in Crete he calls Kouzoulada is found. In Greece Kouzoulada is in the character of place and people, ‘a natural tendency to passion and excess’, the very stuff the norm seekers find ‘queer’.[26] In Cádiz, it defines a shift in register where language is all there is to denote character of excess and passion that ought to originate in people. English does not fully support the meanings he strains for, but it enables him to indicate that feeling has been taken over by sign-systems and codes that exceed the human capacity to absorb.

The text plays with the vagueness of this latter idea, building into the line structure both Philip’s rhetorical flow of protest at a reality made inhumanly artificial and the lack of understanding of that idea in the taxi-driver:

My problem is this, Philip told the driver

Everything I see around me has been thought about

Everything has been made

The driver said he didn’t understand

I can’t but feel verse rhythms here, as well as repetitions, until the driver’s incomprehension breaks the rhythms. The important thing in this formal language use is its emphasis on the need to communicate not on its success. Hence it’s artistic beauty. The lines read themselves in order to be duplicated with a queer difference, a change of language indeed that changes everything and suddenly we are in a state of what might be Kouzoulada. Look at the use of the awkward long line of English below and its insistence without yet, communication until linguistic register as well as the language shifts under him from abstracts to concretes, and the driver starts later to respond as if in understanding and learning:

I have a sense of duplication, a feeling of superfluity, it’s too much to take in, it’s like a kind of bombardment

How wonderful;, he thought, this shift from English into Spanish

The words seemed to be offering themselves

Duplicación, superfluidad

Bombardeo[27]

I suppose the issue is for Notman that he finds passion and excess only in the acts of rape and the resistance men put up to it, whilst women are expected not to. He finds it in the song traditions of Spain and in the heroic resistance to colonisation and takeover by men in Greece. He finds it in firefighting, for boys always want to be firemen. And he finds in the stories of the Southern Cretan Venetian fortress of Frangokastello, which I visited myself as a very young man. I do not know how to read that section of the novel, but that it is thrilling and dark and full of yet unearthed meaning, especially about the defensiveness of male cultures I am sure.

In truth this is a queer novel because it chooses not to fit in, offering only solutions that aren’t solutions and to problems that remain universal yet difficult even to express about the nature of everyone’s relationship to their own modernity and failure to find a place in it, but carry on regardless as if that was normal.

For me Thomson is a great writer. No-one does what he does. Read this one. Do!

With love

Steve xxxx

For other pieces on Rupert Thomson follow these links:

On Never Anyone But You; On Temple Drake (aka Rupert Thomson) [2020] NVK; On Barcelona Dreaming; IN TRUTH I THOUGHT I HAD WRITTEN MORE BUT IT SEEMS NOT. I USED TO JUST READ WITH JOY. HAPPY DAYS!!!!

[1] Rupert Thomson (2024: 380) How to Make a Bomb [published in the USA as Dartmouth Park in 2023] London, Head of Zeus Ltd.

[2] Ibid: 62

[3] Alex Preston (2024) ‘How to Make a Bomb by Rupert Thomson review – struck by sickness, an academic seeks solace in love’ in The Observer online (Jun 31 Mar 2024 16.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/31/how-to-make-a-bomb-by-rupert-thomson-review-struck-by-sickness-an-academic-seeks-solace-in-love

[4] Ibid.

[5] Caleb Klaces (2024) ‘How to Make a Bomb by Rupert Thomson review – a stark study of male rage’ in The Guardian (Sat 13 Apr 2024 07.30 BST) Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/apr/13/how-to-make-a-bomb-by-rupert-thomson-review-a-stark-study-of-male-rage

[6] ibid

[7] Rupert Thomson op.cit: 357

[8] Ibid: 143

[9] Ibid: 33

[10] Ibid: 395

[11] Ibid: 181ff.

[12] Ibid: 194

[13] Ibid: 308f.

[14] Ibid: 361 (see also 339, 358)

[15] Caleb Klaces, op.cit.

[16] Rupert Thomson op.cit: 230f.

[17] ibid: 230f.

[18] Ibid: 295

[19] Ibid: 351

[20] Ibid: 349

[21] Ibid: 99f.

[22] Rupert Thomson (2024: 380) How to Make a Bomb [published in the USA as Dartmouth Park in 2023] London, Head of Zeus Ltd.

[23] Ibid: 152f.

[24] See ibid: 82, 200ff & 243 respectively.

[25] Nicholas Wroe (2013) ‘Interview: Rupert Thomson: a life in writing’ in The Guardian online (Fri 8 Mar 2013 10.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/mar/08/robert-thomson-life-in-writing

[26] Rupert Thomson, op.cit: 219

[27] Ibid: 63