The shooter shot – a name for the meta-art of civil disturbance. This is a blog on Alex Garland’s Civil War. See it.

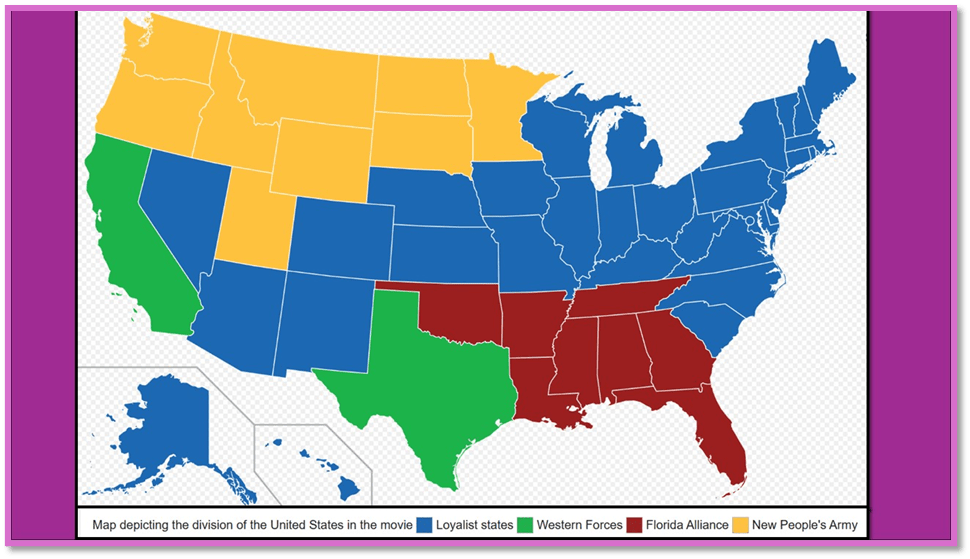

The film company A24, mainly responsible for this film takes the civil war scenario in the USA we might think seriously, else it would not have produced a map showing the distribution of states ‘loyal’ to the status quo and the various secessionist groups in it, of which the rationalised coloured version from Wikipedia is shown below. However. It would take some kind of care to plot the film in ways that made the origin of each of the groups confronted on a journey of four people, variously connected to journalism, in the film to Washington DC by a circuitous route.

By ImStevan, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=146956940 Based on a map produced by A24 (https://gizmodo.com/civil-war-2024-map-united-states-alex-garland-a24-film-1851382999). Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civil_War_(film)#/media/File:Civil_war_2024_map.svg

And on reflection, I cannot see the point of working out such detail. The feel of the film is very much that it is difficult to know who is engaging in the things they do and why and in whose name they do them. This is the kind of anarchic chaos one would expect in civil war I think and it does not trouble me that I have no clarity on these issues as it does the professional reviewers.

For me, Alex Garland’s film Civil War is neither about divides in political America (with or without the backing ideologies of those divisions represented) or the nature of journalism per se, the topics that are consuming criticism of it, but about the nature of stilling or manipulating motion in cinematography and / or photography. It is very much a film of remarkable cinematography, that uses stills in the story-telling and as properties both handled and discussed by the characters as part of its varied means of telling the story. I hope I am not just jumping on a bandwagon favouring the meta-narrative, for this theme seemed to me to be self-evident, part of the necessitated experience of watching and listening to the film with a view in which cameras and camera accessories are part of its discourse, and where shooting occurs using cameras or guns in almost interleaved and certainly simultaneous ways.

Since, I saw Civil War yesterday and had the thoughts I want to expound later, it came as a surprise to me to read a mass of reviews of it and interviews with the Director. None of the latter felt that enlightening. There is a lot of abuse flying about, of which the strongest may be this from Charles Bramesco:

With its bands of marauders, thinly drawn archetypal characters, and prevailing thirst for blood, Civil War is more like a shameless B-movie in solemn arthouse drag, in denial of a distasteful streak that could have blossomed into far more cutting commentary if properly nurtured.[1]

Peter Bradshaw, acknowledging, without quite saying so the picaresque structure of the narrative as a journey by an oddball set of journalists into a heart of darkness that is its construction of The White House in Washington DC, says with more circumspect and very English waspishness:

For their journey, Garland gives them freaky and surreal episodes and encounters, underscored by interesting and emphatic musical choices that mimic their dissociative trauma, although sometimes these episodes will be suddenly curtailed. At one stage they’re pinned down by a sniper in an abandoned outdoor play area with Christmas music bizarrely playing … the next thing we know they’re safely back in the car. How? It’s a strange, violent dream of disorder, drained of ideological meaning.[2]

We could stand back from Bradshaw’s last sentence and wonder if he is describing the film or the aim of political popularism as an imposition on our history, which, though led from the right currently, aims at the maintenance of a status quo that neglects to notice its underlying disorder and the fact that we never get ‘ideology’ delivered straight, only mediated as common-sense or a pragmatic response to events.

The film opens with a president rehearsing his speech to the nation and then conducting it on TV watched by hard-bitten journalists in a hotel where many journalists are gathered. The point of the film seems to be the need of jobbing photographers, in particular, can represent the disorder that flows across their senses and half-comprehending attention and the frame it for passage on to an audience. In the film in the shots taken (of photographic film at least), the only thing that moves is my take on it as I ‘take’ the photograph, however delusional or essentially lacking in any sense is the whole picture. I say nothing moves but me, but it does – it is that the movement happens around me and without me really knowing why it is happening as I try to focus on one incident,, which, for a moment, I can still in its motion and capture in either the camera’s or observer’s eye. In the following shot we see how this typically happens. Military action takes place, here on a large scale, which in panning out also involves the ubiquitous noisy helicopters of the film. The motion is enveloped in the areas out of focus in the shot, only the still observer, the only journalistic writer, Joel from Florida (played brilliantly by Wagner Moura) not embedded with a unit, STANDS and sees and looks frankly puzzled.

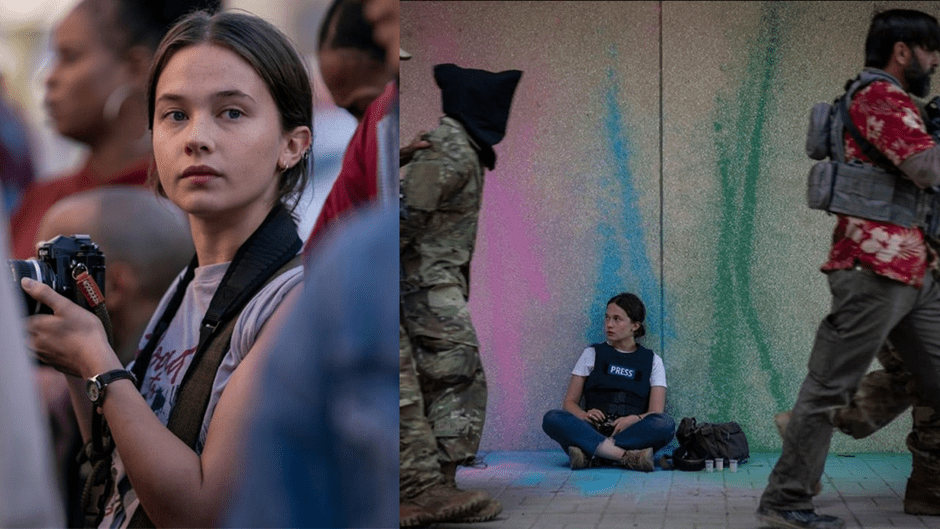

See it too happening around the novice photographer, aspiring to be a Lee Miller, or Lee Smith (the latter the photographer played with stony appropriateness by Kirsten Dunst), Jessie Cullen (Caillie Spaeny) in the shots below. Caught early in the film in a scene that will become chaos after terrorist attack, she stands still with camera and looks out of the screen, with her camera pointed to another focal point. She is our focal point, the movement around her blurred. Even more telling, a scene amidst the journey of the journalists to Washington where one set of fighters temporarily triumphant lead black-hooded defeated fighters to execution across our field of vision as Jessie sits motionless caught in the gaps of their passing, the wall behind her smeared with colours we cannot decipher with meaning. The issue is I suppose that both eyes and lens tend to miss a lot that moves on around, across or away from you, and yet we have no other way to frame a shot, even in cinematography but in stilling, at least relatively one part of it.

Perhaps the finest scene, recalling a trick from Midnight Cowboy, is that wherein external motion occurs as a reflection in a car window to a camera strapped to the moving vehicle itself, while holding still Dunst’s ‘look’ created for Lee which records her sense of responsibility for all this chaos, though a responsibility that isn’t hers (or all hers as it seems in her look) in a still facial shot.

Above, in passing, I mention the fabulous helicopter movements in scenes preparatory to battle as armies move on above (in Washington we see them though at night mid-battle) and in an interview with Ellen E. Jones

Garland’s sombre, anti-war stance doesn’t prevent Civil War from producing some awe-inspiring spectacles of US military might, with helicopters a recurring motif. “They’re very visceral objects and experiences,” he explains. “They make much more noise than people expect, and the noise has a kind of fast, heartbeat pulse in it, that your own pulse rate matches. I’ve done a lot of flying in helicopters for one reason or another. Not least work, actually.”[3]

It’s interesting by the way that despite Jones calling it ‘US Military might’ the largest helicopter transport scene is of forces working for the Western Alliance, the one time it is clear what side we are seeing for we hear talk with journalists embedded in that moving army. As Jessie is mentored as an aspiring journalist photographer, Lee asks her to practice on one stilled (because shot-down and now abandoned) helicopter that the group come across on their journey before being pulled into any action by one or other side – each time it is unclear who they temporarily ‘side’ with to take photographs for photographs can ONLY be taken from one side – that is perhaps their nature).

The use of the stilling nature of photography, creating as it were a STABLE image is well known to us of course in political ideology and propaganda. The film starts, as said already, with the flustered fussy over-mobile rehearsal of the President of the United States (POTUS), in his unconstitutional third-term of the speech that has to be, and is, delivered in an atmosphere of quiet and unmoving authority. The result is what we know – whether in the Press Room of the Trump or Biden White House – a set-up that owes more to the issues behind photography and contemporary cinematography than to what we loosely call reality ‘reality’, political or otherwise.

Meet el presidente … Nick Offerman in Civil War. Photograph: Murray Close/A24

In my view, the duty of art is to be open about the politics intrinsic to the methods and contents expected of art, which primarily is to be fully conscious of the means by which artistic representation is enabled – in this case through the arts of cinematography, photography and sound, the filmed audio-visual shoot. Alex Garland as a cinematic artist knows how important it is to be conscious of the production of a film shoot. Film critics are talking heads who do not have to imagine how representation through a mediating lens has its own politics – mediation is necessarily political if not always consciously so in the selection of a perspective and of which part of the subject will be represented, the framing of the margins of that selection and the modification of the internal parts of the picture frame – delineating background and foreground, choice of focal point. In a war these features are often pre-decided by the ‘side’ the shot is taken from. But these journalists travel between groups in episodic stories where it is not clear who is on whose side, as necessarily occurs in internal civil war.

Both Bradshaw and Bramesco think Garland has missed real-world politics and art’s responsibility to politics. Bradshaw says Garland ‘stages a spectacular if evasively apolitical “civil war” in this futurist-dystopian action thriller’. This involves he continues view of civil war as a ‘fence-sitting reluctance to name any of the issues that might actually result in a civil war’ and posits that this is done cynically so the film ‘can be enjoyed by the widest possible audience base’.[4] This negative evaluation is even more clearly phrased in a stunning passage by Bramesco, which seems to skewer Garland on a point of the director’s own sharpening:

As he has clarified again and again to the point of insistence, his interests lie closer to journalistic matters in the abstract. “The kind of journalism we need most – reporting, which used to be the dominant form of journalism – had a deliberate removal of a certain kind of bias,” he told Polygon. “If you have a news organization which has a strong bias, it is only likely to be trusted by the choir to which it’s preaching, and it will be distrusted by the others. So that was something journalists used to actively, deliberately, consciously try to avoid. … And then the film attempts to function like those journalists.” Such a statement betrays a stunning misunderstanding of the profession’s functioning and purpose, which have always been shaped by conscious decisions of framing. Considering the material at hand, it’s hard to accept that even Garland buys his own line. Is perfect impartiality the intended takeaway when Kirsten Dunst’s battle-hardened shutterbug instructs a gunman to pose in front of his bloodied captives like they’re line-caught tuna?[5]

This is a very unfair reading of what Garland says. Because Garland lauds the attempt of journalists in the past, like his own father, to ensure ‘a deliberate removal of a certain kind of bias’ does not mean Garland is trying to make a film pretending to ‘perfect impartiality’. Indeed I would say the point of the film that avoiding ;certain kinds of bias’ does not mean that all bias is avoided for some is intrinsic to the narrative methodology of visual representation such as the selection of a ‘point of view’, especially in war (hence I think the contrast between our weird collection of itinerant journalists, Lee, and those embedded with the Western Forces seen later such as the character Anya (Sonoya Mizuno playing the British reporter covering the Western Forces’ advance on the Capitol). The way this is done is by making a feature pf the film a thematic strand dealing with the nature of a ‘shot’, ‘shoot’ or ‘shooting’, whether taken from a camera or a ballistic weapon (large or small). Indeed this is the focus of the film (to use yet one more appropriate ambiguity on the word ‘focus’).

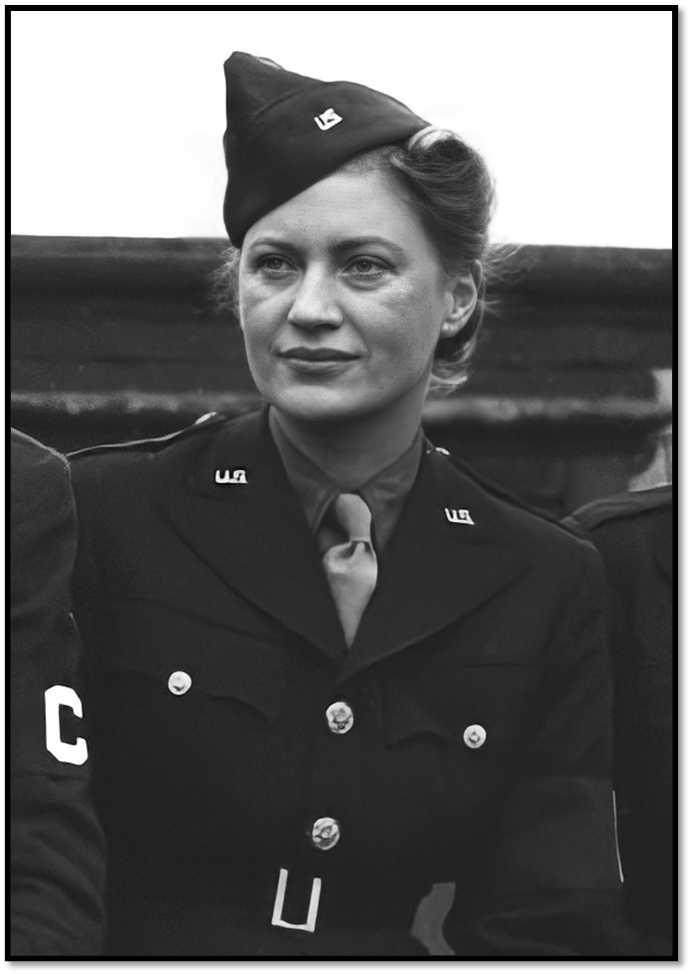

That illustration Bramesco uses above to illustrate his point about the film is a gross reduction of what the film itself actually uses that chosen section to show. The section referred to is that where a highly stereotypical ‘redkneck’ American displays the military captives Bramesco describes as ‘line-caught tuna’ (still alive) and requests advice from the journalist about where to stand for best effect of framing a shot of him with the captives. For Bramesco to tell this filmmaker that ‘framing’ is important in journalism is both unintelligent and unobservant, for the issue for the film is not ideological framing or side-taking, or the representation of political, or even military, framing of perspectives in the branch of journalism of concern – photo-journalism or cinephoto-journalism. The lead role by Kirsten Dunst is after all, as a conversation between the photographer and her reluctantly-gained young female protegee reveals, is named in order to recall Lee Miller.

Female war correspondent Lee Miller who covered the U.S. Army in the European Theater during World War II (U.S. Army Center of Military History)

That reference to Miller is no accident for Miller bound together an interest in the use pf photography in art, fashion and art critique, as the associate and equal as an artist of Man Ray, Alred Beuys, Roland Penrose ( eventually Picasso’s first biographer with Miller’s photographs). The issues in framing a photograph are aesthetic and pragmatic it tells us as well as representational. All art requires knowledge of its mode of mediation based on an understanding of the limitations and potentials of both still and motion photography, in this case, particularly in relation to placement of subjects in relation to camera angle here. (I have already looked at above how the stilling achieved by focus conflicts with the handling of contingent time that occurs alongside the selected foci of art). The cruel joke of this scene is that the ‘redkneck’ wants to know where he will look best in relation to his suspended prisoners in the photoshoot to be taken. This is in a photographer’s skillset but the photographer here, Lee, realises that placating him enables the shot, wherein she will try to capture the cruel essence of what is there whilst she and Jessie enable their survival of the process (together with the shot, should it be later used, which I doubt). The issue here could be described as dealing with the relationship of the aesthetics of a photoshoot(what looks best where within the frame) and its contingent and teleological meanings. Let’s be clear how I use these latter words. The teleological meaning of a shot is the end it aims to achieve, the contingent meanings are those circumstances it addresses in the process of its making. In the case of the redneck’s photograph most of the meanings are contingent – aimed at placating the redneck to reduce the danger and likelihood of survival to the two photographers. Bramesco misses that.

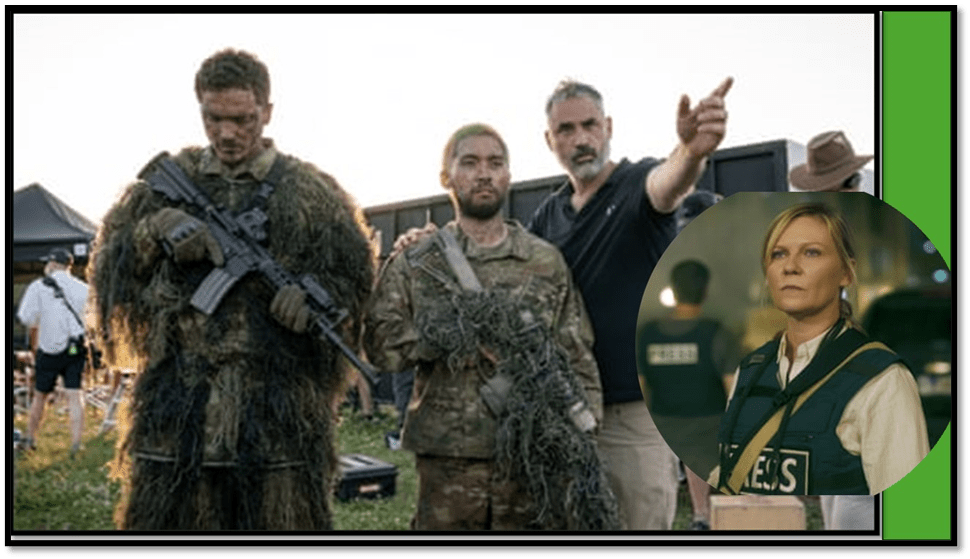

Some points made by the critics’ reviews are just petty, and Bradshaw’s insistence that Dunst plays Lee with ‘a permanently sorrowful and disapproving schoolteacherly expression of dismay’ is one such. Dunst represents in this film a sense of responsibility that barely understands for what she is responsible, but it is to do somewhat with the look promoted by the idea of the press – their look at things and the look they promote. I found that in Dunst’s brilliant look as in the example below. Worse is that both think the film is made for the money only. No one is free of financial self-interest of course in our society, least of all culture journalists, but surely the idea that this is just a film ‘servicing the audience’s basest desires’ for meaningless violence or, if it serves the director’s professional interests only because Garland likes ‘commanding squadrons of extras in choreographed chaos’ are cheap, especially near to a picture of Garland just doing that (also in the collage below).

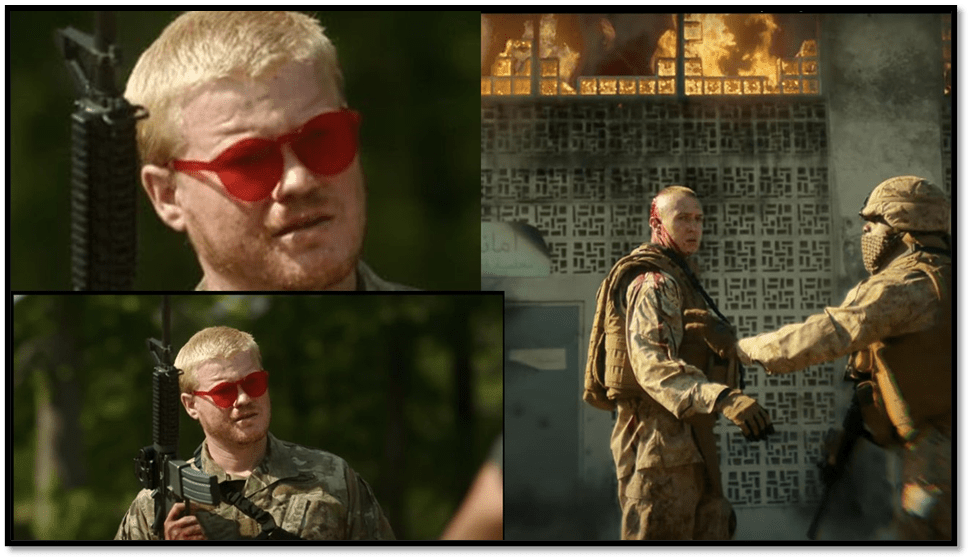

Hence I will leave the critics alone and develop my own thoughts with no belief that they have authority or are looking for such. They just record an absolute delight in this film from a person not overly keen on liking displays of either bloodthirsty extra scenes or overacted iron schoolteacherly ladies. But the still of Garland with extras above does point out that he takes the shooting that is part of warfare seriously in this film. And in my view, he does so because he will find analogy in it with the dangers involved, to the shooter as well as shot, of photograph or cinematographic shots. Let’s start with the random shooters. The one featured below is very trigger-happy but like to hide his interest in shooting people from them to the last minute behind beguiling, and hence sinister, pink glasses.

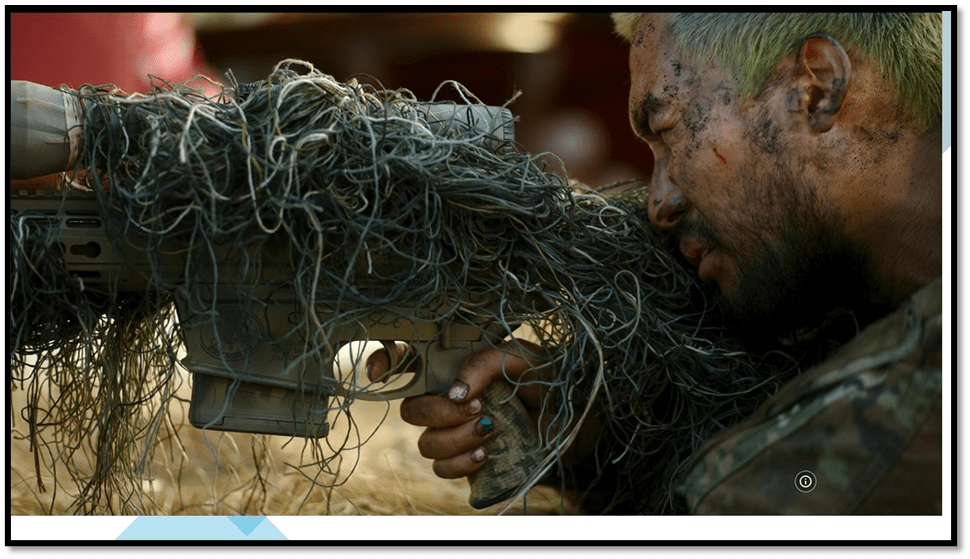

In the collage above, I place him next to another still in which a shooter has been shot and advertises it with this conversation with another shooter to who he gives information, presumably for the next shot to make it the more successful. Critics have found ludicrous a scene I find haunting – where the itinerants come across an emptied field of an abandoned Christmas fair with all the appropriate future. They are being shot by an unseen sniper but will owe their rescue (the critic referred to missed this) to the shooter who the photographers become fascinated in, especially Jessie. See him below. We are inclined to notice in the close-up framing the highly decorative nail-polish he uses. He picks him out as the shooter shot in which the shot is different in each case. I loved this haunting beautiful but disturbing scene of what underlies the hypocrisies of Western Christmas.

Now look at how the film focuses on the taking of shots, including the additional accessories needed for their varied kinds, as with the large telescopic focus used on Lee’s camera in the picture on the left in the collage below. And look too at how the gun-mounts look like camera-easels behind the camerawoman Lee and her reporter in the blurred background, rendered passive as he usually is in the film, for words, perhaps, are secondary in shooting as the President learns.

The placing of Lee behind a camera for motion or others to be blurred behind her is the more thematic in that Jessie is taught this role despite Lee’s initial reluctance to pass on the dangerous skills of shooting. In the collage below we see Lee training Jessie’s eye to seek and find first the lens and then her subject or topic through it (as with the downed helicopter too. In the picture on the right in the collage below, Jessie is backed still, still being trained as it were, but by a word reporter, Joe; And she comes face-to-face with a nemesis – a gun that might (but doesn’t – for here they are assumed allies) shoot her in a much more messy way. The vulnerability enacted by this superlative actor reinforced by the enacted care and support of her ‘carers’ is tremendously convincing and moving.

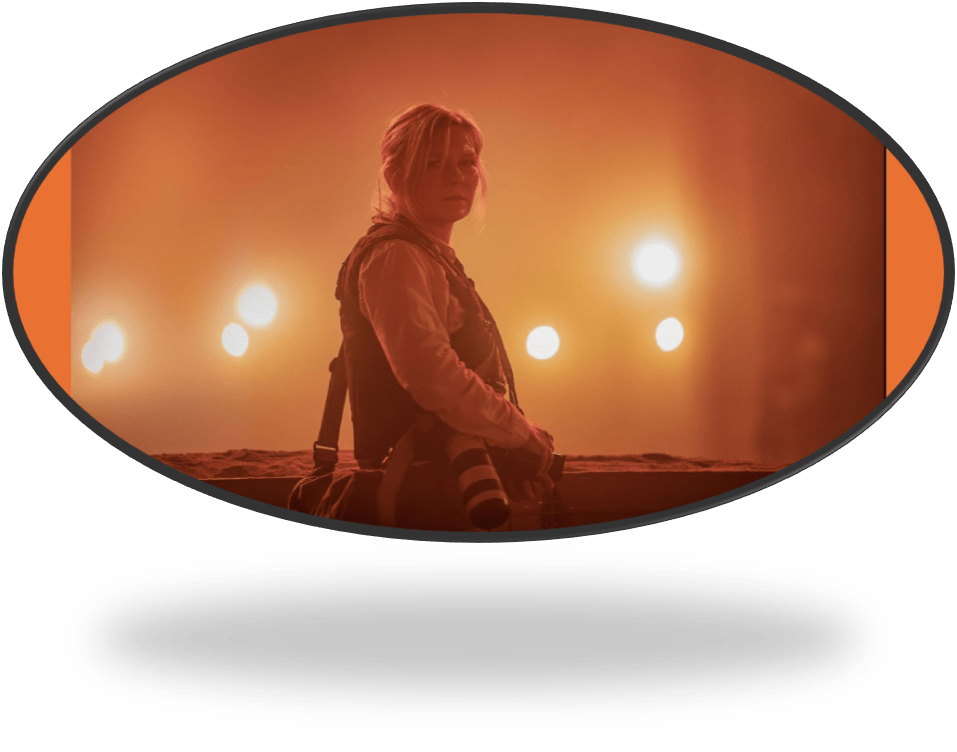

It will lead her to autonomy as a photographer in Washington DC in the dark, though still rescued by Lee at a sticky moment in order to visibly pass on her camera strap to younger flesh. The fire behind Jessie’s head almost seems to symbolise the danger she both confronts and knows to lie behind her in her chosen role.

Having said this, despite brilliance in all roles, especially the paternal sacrifice that is Stephen McKinley Henderson as Sammy, a veteran journalist for The New York Times and Lee and Joel’s mentor, this film is Kirsten Dunst’s and for that reason I rankle still over Bradshaw’s bitchiness about the range of her acting cited above. For she is perhaps archetypal but an archetype not always confronted – the woman who believes in the autonomy of thought, action and feeling of independent women, women who are the guardians of a quartet of misfits – patriarchal father-figures, apprentice daughter figures, a less strong male partner and various rather silly lads who get in on the act (Tony – Nelson Lee – and Bohai – Evan Lai). So let’s end with another shooter shot.

The responsibility for what see sees is lit from behind, almost as if with stage lights. And it is us. It really is. A superhero of our times for whom art, war and truth in both matter. Lee Miller perhaps.

Please see this great film for yourself.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Charles Bramesco (2024) ‘Civil War is an empty B-movie masquerading as something of substance’ in The Guardian online (Mon 15 Apr 2024 15.30 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/apr/15/civil-war-alex-garland-review

[2] Peter Bradshaw (2024) ‘Civil War review – Alex Garland’s delirious dive into divided US society’ in The Guardian online (Wed 10 Apr 2024 13.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/apr/10/civil-war-review-alex-garland-kirsten-dunst

[3] Ellen E Jones (2024) ‘Civil War film-maker Alex Garland: ‘In the US and UK there’s a lot to be very concerned about’ In The Guardian online (Sat 30 Mar 2024 11.55 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/apr/15/civil-war-alex-garland-review

[4] Bradshaw, op.cit

[5] Bramesco, op.cit.

2 thoughts on “The shooter shot – a name for the meta-art of civil disturbance. This is a blog on Alex Garland’s ‘Civil War’. See it.”