Francis Spufford(2024) Cahokia Jazz London, Faber & Faber. A preparatory look at the novel prior to seeing the author on the 27 April 2024 at 4.15 – 5.15 at the Queens Hall, Hexham

For my review blog of an earlier novel, Light Perpetual, by Spufford see this link. In fact, I think my take on this novel possibly is dependent on things I say about the writer therein, but I will quote the relevant bit later. If you glance through the reviews, you can’t help but find that Cahokia Jazz does not make critics comfortable. On the positive side, Alex Preston in The Observer calls it unequivocally a ‘classic of alternative history, further evidence of Spufford’s range and subtlety as a novelist’. Preston also thinks the novel has a ‘great deal to say about contemporary America, particularly the issue of race’. But, although those words seem unequivocal as I call them Preston is unsure whether every reader will be convinced by the novel ‘having to interrupt the rollicking plot to catch up the reader with the onward march of (alternative) history. It feels like it’s a problem that is baked into the genre itself: if you are going to rearrange the furniture of history, it creates a lot of housekeeping’.[1]

All of these critics point to novelist who may do all this better although none use the rather large hint in Spufford’s acknowledgements that trace a debt in the making of history from the counterfactual to Ursula Le Guin, whose ancestry includes an actual character in Spufford’s novel. Professor Alfred Kroeber.[2] Some are downright antagonistic to the counterfactuals employed. For instance Ivy Pochoda in The New York Times says:

Cahokia Jazz presents an alternate America in which the variant of smallpox introduced to the United States during the Columbian Exchange was less deadly, conferred immunity after infection and didn’t decimate the Native population. … (Smallpox immunity aside, how these Native people managed to avoid white America’s genocidal imperative is a mystery mysteriously not part of the plot.)[3]

This is more damning than it sounds if you read modern Native American fiction of the class of Tommy Orange (see the blog at this link for a view of his latest novel) , for it really exonerates most white Americans from intentional genocide, seeing the rot of racism in a rather comic version of the Klu Klux clan, if frightening in some parts, aided by big business and the American-European crime cartels, suspiciously largely German in the novel. I have my eye on that tendency as too forgiving of colonial settlement in new worlds.

And for some the counterfactual world is not only politically suspicious, if with its heart in the right place, but ploddingly reconstructed. Xan Brooks in The Guardian puts it kindly, saying ‘Cahokia Jazz … has its hands full, gamely juggling exposition with action, the conjuring of a world with the demands of a machine-tooled murder mystery. Gears grind and wheels spin’. Despite the mechanistic feel of that description, Brooks sees the virtue of the novel in its playfulness:

Spufford’s approach is more playful than prescriptive, more akin to that of an expert model engineer. He builds a world and paints the scenery, provides a physical map and useful background information, to the point where the act of creation becomes a story in itself. …

It is a novel with a detective noir thriller plot but is ‘at least as interested in the investigation of its constructed metropolis as it is in solving the murder of lowly, luckless Fred Hopper’.[4] Brooks just admires how Spufford does all this, as does Preston. The latter even thinks it good that the book concocts a full-blown language from known fragments of different Native American dialects of which ‘the reader slowly picks up a working knowledge’.[5] I found that to be indeed the case. It is largely a matter of lexis rather than syntax but I felt somewhat familiar with Anopa phrases by the end. There is in fact almost a tutorial on it as we puzzle out the relation of language to English translation on receiving one putative villain’s address in Anopa.[6] The investigation of a dark city is the noir detective thriller at heart Brooks say (and I think rightly finds a hint of Raymond Chandler and Dashiel Hammett. The noir novel is, as in their grim settings:

a licence to roam – an excuse to kick open doors and interview all the suspects. … Spufford’s invented city – built around the true-life Cahokia Mounds, near a village called St Louis – is a place of blind alleys and dark corners. It’s thick with mystery and in thrall to arcane tribal lore. ….[7]

But for Ivy Pochoda, if the novelist overworks all those elements, this leaves the reader too with much reconstructive work to do in the act of reading. At the end of her piece she says that ‘that, my friend, just might be too much work for me’. Her opening just about sums up WHY other readers might agree:

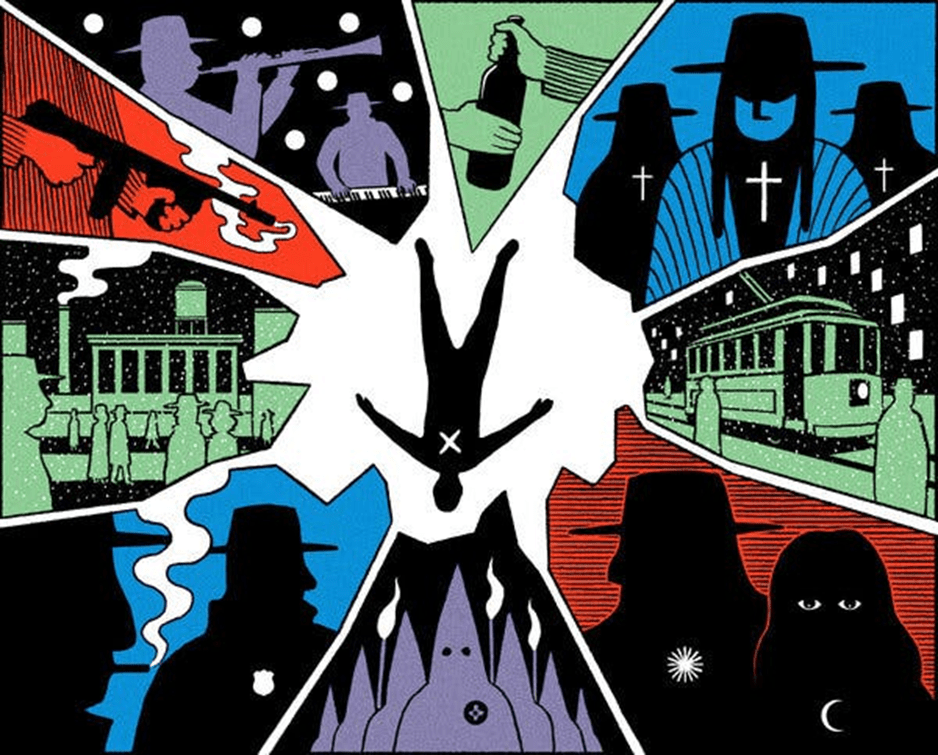

Reader, let me ask you a question. How much work are you willing to do to dive into a new novel? Do you want to step into a speculative world frustratingly close to our own? Do you want to spend time in an imaginary city constructed with the world-building minutiae of a high fantasy novel? Do you want to engage with new forms of government and religious sects? Are you cool if there’s foreign language peppered throughout? How about the Klan? A Red scare? A nascent F.B.I.? A love story? Do you also want jazz? And do you want all of this to be part of a detective novel?[8]

The ’New York Times’ pictures the elements seen by Pochoda in a rather pleasing graphic (above). Credit…Jérôme Berthier Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/06/books/review/cahokia-jazz-francis-spufford.html#

There is more than one question here and that may be the point. Nevertheless I agree with the British critics about the novel’s engaging playfulness, even in puzzling out the Anopa and Latin equally in it. I have a ‘yes, but…’ feel about Pochoda’s genuine concerns, particularly over the simplification (and perhaps whitewash) of race issues. The playfulness is engaging. It engaged me, even the puzzles over the translation of Anopa and Latin equally. But Brooks and Pochoda may take the ‘playful’ defence further than I do. For I think, just as I dis about Perpetual Light, Spufford has a point to make. Over that last novel, he was interviewed by Kate Kellaway in The Guardian in 2022, who quizzed him, in a kindly way, about his tendency to create a sermon, even amidst the play of art. His wife, Jessica Martin is a canon at Ely. Kellaway almost taunts him that in his book, he makes her think: “Come on, Francis, you have to get into the pulpit.” He replies to her:

No! I haven’t – I have the freedom of being a layperson, I don’t have to speak for an institution. I’ve preached the odd sermon by invitation and found it very nerve-racking. Performing something usefully devotional – it’s not my thing. And my wife is really, really good at it.[9]

Unapologetic is indeed a Pascalian defence of God’s existence aimed at the irreligious sociobiologists. Richard Holloway describes it sympathetically thus in conversation with Spufford, quoting him below:

Like the rest of us, he doesn’t know if there is a god. “And neither do you, and neither does Richard bloody Dawkins, and neither does anyone. It not being a knowable item. What I do know is that, when I am lucky, when I have managed to pay attention, when for once I have hushed my noise for a little while, it can feel as if there is one. And so it makes emotional sense to proceed as if he’s there, to dare the conditionality.” His book itself is an act of daring, a message from the frontline of an old and bruising war.[10]

Spufford in 2022

In my blog on Perpetual Light I sensed that my quarrel with Spufford would probably be because I don’t accept Pascal’s Wager, keeping an eye on the comforting possibility of communion with deity. I put it thus in my blog:

This is the best example of what I see as Spufford’s attempt to fashion belief out of the doubtful and uncertain stuff of time. Of course, readers like me depart Spufford’s authorisation of such moments precisely then and refuse to see more than the rhetoric which points to that safe place beyond the world and mundane human knowledge. Religion as a set of propositions will always have that effect on the determinedly non-religious. It is, as Pascal would say, the risk we take in the wager that God and eternal salvation are myths.

So, though for this reader, Spufford’s harmonic and infinitely well-lit notes ring false, I admire the novel’s prose. Literature though, I think, can only confirm belief that requires to be sustained outside its pages not create and maintain such beliefs. What do you think?[11]

And the critics miss the fact that Spufford uses arcane religious lore, even a sympathy with certain syncretic experiments of the colonising Jesuit movement with Native American populations, For these are taking more seriously in this admittedly playful novel than any of the critics above would have us think. The novel’s counterfactuals build on genuine Jesuit attempts to syncretise Native American religions with each other and with Christianity. The religious doctrines syncretised include even – and this is a major contradiction in the novel that even puzzles the detective lead half African Black and Native American, Joe Barrow- Aztec blood sacrifice.

The traditions of Cahokia Native Americans (named takouma in Anopa) are not Aztec, and would not support the ritual murders of some of the shadier characters of the novel of men or animals but do include a ‘purged and Catholicised form’ of it Professor Kroeber says.[12] And hence the freedom the novel takes in reinventing Christian myth syncretically. The wild Thrown Away and civilised Lodge boys are knights of Christianity but also to sides of Christian rapture, Joe Barrow makes a Christ-like sacrifice whilst hurling down his dark other, Drummond, like Satan from a height to his fall, The blood of sacramental wine, sometimes purloined in the novel, becomes the source of redemption. Near the end the Police Chief served by Barrow says he has moved from ‘disgrace’ to ‘redemption’.[13] The novel even stages a cod Immaculate Conception with the help of some gritty and sweaty secreted sex.[14]

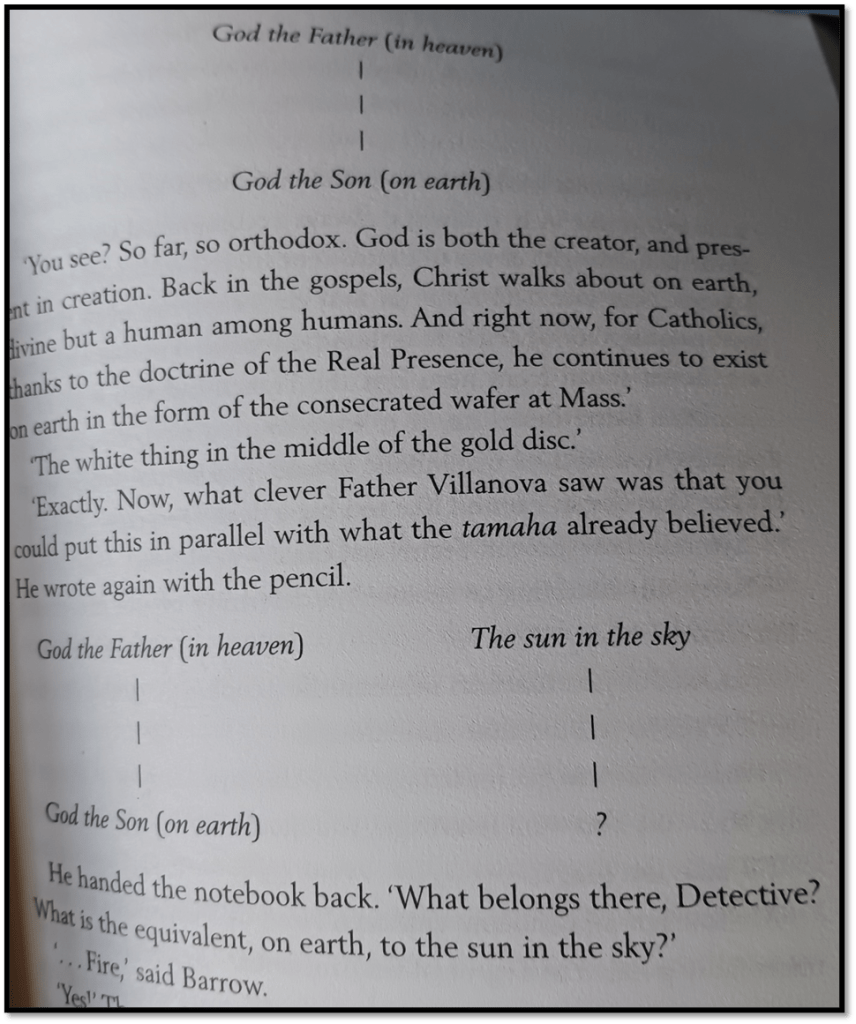

The Moon Princess becomes a female replacement of the Sun King. Does anyone notice that that means she is the ‘woman clothed in the sun’ in Revelations and the answer to one of the novel’s puzzles. Let’s take a look at that puzzle as it appears in the novel. Well the novel provides its own answer, the one the real Jesuit father Villanova posited that the ‘sun in the sky’ is to ‘God the father’ as a sacred flame’ on earth is to God the Sun.

Spufford (2023: 343)

However, those answers are brought into being in a conversation (that photographed above) between MEN (Professor Kroeber and Barrow). At this point of the novel unbeknownst to either of those MEN, the novel convoluted stories are beginning to reconcile the sun with the moon, night and day sky, and male with female sacred function (I hope that isn’t a spoiler – I think you would have to know the novel to know what I mean so I think not). The equivalent of ‘The sun in the sky’ is in Christian eschatology, the ‘woman clothed in the sun’, from The book of Revelations. Such an idea too fits with the Marian symbolism in the novel.

Woman clothed with the Sun or Woman of the Apocalypse – main metaphor in the Book of Revelation – painting by Ferenc Szoldatits

When the Sun-Man anoints the Moon, also known as ‘Our Lady ’, in front of a football stadium audience, the imagery of the Madonna as Woman clothed in the Sun is complete, but Barrow is surrounded by a Madonna blue sky at many times. As he runs from the office to Francis Xavier University the ‘sky was a bright blue now, as perfect and unbroken as if it was painted on. As if someone had dipped a brush in the colour used for the Madonna’s cloak’.[15] Here is the sun in the sky so to speak: ‘The Man was making Her his heir. After him, there would be for the first time be a Woman of the Sun’. But still stood, as in Marian iconology on the Moon she was and still is.

It would be inappropriate to see a play for a Catholic reading of this novel. All of the symbols in this novel are of questionable reality and in many ways embrace their theatricality and artifice, just as the Madonna blue skies seem painted. From our first introduction the Man of the Sun proclaims that people in the everyday world:

… miss a dimension. Symbolism, Detective, what things mean. … because, of course, unlike my ancestors I am a symbolic King, not a real one. And yet that is not nothing, Mr. Barrow. Sometimes symbols move solid objects, sometimes they act on flesh and blood. … Without the meaning of things, without the stories people tell about them – that people believe about them – you can’t understand events, detective. You can’t understand this city.[16]

But the meaning of things in the city and the story are constantly shifting, even its colour symbolism. There is a lot of spilled blood in this novel but it serves its purpose, together with all the variations of RED things in the novel, and the meanings attached to redness, which might be the hope, or the fear of Communism in the States of the imagined period, or of blood, or the red of communion wine, or of the skin of a native American or that invisible in the roter niger that is the name Barrow is called by the Klu Klux Klan gangs.

I think I only need to add that this symbolic dimension is the place where the arcane myths of this book become not only local colouring in the creation of a counterfactual culture but attempts to create understandings that are in themselves sacramental – the outer and visible sign of an inward and invisible grace as St Augustine phrased them. In Christianity the denote initiation into religious mystery and just because this is a hybrid novel of detection, alternative history and cultural exploration does not mean it does not symbolise truths inwardly to its author. I think it does. I cannot share them anymore than I could with Perpetual Light, but I think you probably haven’t probably read the novel if you think of it as merely playful or worse tendentious, about the politics of community, at its best in jazz, at its most scary in the Klu Klux Klan.

Interleaved photographs from the novel’s sections.

Geoff and I are seeing Francis Spufford on the 27 April 2024 at 4.15 – 5.15 at the Queens Hall, Hexham . If I have more to report I will append it to this blog. But at the moment my toothache, earache, and headache from the dratted wisdom tooth dry socket means I probably won’t even revise this yet.

With love

Steve xxxxx

[1] Alex Preston (2023) ‘Cahokia Jazz by Francis Spufford review – a ‘what if’ classic’ in The Observer online (Mon 25 Sep 2023 10.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/sep/25/cahokia-jazz-by-francis-spufford-review-a-what-if-classic

[2] Francis Spufford(2023: 478) Cahokia Jazz London, Faber & Faber.

[3] Ivy Pochoda (2024) ‘A Speculative Jazz Age Noir Brimming With Murder and Conspiracy’ in The New York Times online (Feb. 6, 2024). Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/06/books/review/cahokia-jazz-francis-spufford.html#

[4] Xan Brooks ‘Cahokia Jazz by Francis Spufford review – fabulously rich noir’ in The Guardian online (Sat 7 Oct 2023 07.30 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/oct/07/cahokia-jazz-by-francis-spufford-review-fabulously-rich-noir

[5] Alex Preston, op.cit.

[6] Spufford, op. cit: 110

[7] Brooks op.cit.

[8] Pochoda, op.cit.

[9] Kate Kellaway (2022) ‘Francis Spufford: ‘I felt that to call myself a writer would be a boast’ in The Guardian online (Sat 12 Feb 2022 18.00 GMT) available https://www.theguardian.com/books/2022/feb/12/francis-spufford-i-felt-that-to-call-myself-a-writer-would-be-a-boast

[10] Richard Holloway (2012) ‘Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity Can Still Make Surprising Emotional Sense by Francis Spufford – review’ in The Guardian (Fri 14 Sep 2012 08.00 BST) Available At

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/sep/14/unapologetic-christianity-francis-spufford-review

[11] https://livesteven.com/2021/02/19/we-are-so-many-every-single-one-the-centre-of-the-world-around-whom-others-revolve-and-events-assemble-so-much-necessarily-lost-skated-over-ignored-when-the-mind-do/

[12] Sufford op. cit: 166

[13] Ibid: 421

[14] Ibid: 443

[15] Ibid: 308

[16] Ibid: 32