The holes in Tommy Orange. The author’s account of multiple contemporary Native American life-stories across time-and-space. This is a blog on the massive over-significance of Tommy Orange (2024) Wandering Stars London, Harvill Secker.

The character Sean Price in Tommy Orange’s Wandering Stars is defined by a hole in the texture of social meaning: he feels to be neither man nor woman, but not comfortable either as non-binary. He feels unacceptable as LGBTQAI+, except perhaps under the ‘plus sign’, where no word is allocated. He wants not to be a man under the conditions offered but knows he is a beneficiary of such conditions because he is read as a man by others. He cannot define his racial, ethnic or cultural identity, either, even from skin colour (he is a Black adopted son of white parents), though interpretation of that intervenes in the process. Jonathan Escoffery in The New York Times writes brilliantly well on this regarding Sean Price and at length.

Orange expands his focus on identity to consider the fraught relationship between race and blood. We hear from a high school student named Sean Price, an adoptee raised by white parents, who has just received the results of his DNA test. “He’d already assumed he was part Black,” Orange writes. “There was no mistaking the look you got if you were assumed Black or part Black in a white community — whether you were or were not all or part.”

Blackness, according to Sean, lies in others’ assumptions and becomes most pressingly about how one is perceived and treated. The point is emphasized when Sean and another adoptee friend make a habit of riding the city bus from the Oakland hills down into predominantly Black neighbourhoods, where they are unbothered, and where they can “disappear completely” from the white gaze. But given his upbringing, “Sean didn’t feel he had the right to belong to any of what it might mean to be Black from Oakland.”

Sean considers what to make of the DNA results, which reveal European, Native American and African ancestry, and determines that “he couldn’t pretend to now be Native American, not white either, but he would continue to be considered Black, holding the knowledge of his Native American heritage out in front of him like an empty bowl.” Data about his ancestry alone isn’t enough to allow him to feel he can claim it.

Later, Sean seeks guidance from his schoolmate Orvil Red Feather, asking, “So, like, can I say Indian?,” to which Orvil responds, “If you’re Indian.” The novel does not include the percentages that typically accompany these DNA test results, perhaps to dissuade readers from attempting to construct Sean’s identity on his behalf. It’s as if Orange is saying, You can’t decide this for Sean.[1]

Hence when an empathetic teacher tells Sean to ‘find your people’, he feels no further advanced on his quest for personal space in which he feels he belongs and it remains a hole that can’t be filled – though alcohol and drugs as elsewhere attempt to fill it.[2]

Sean Price is a relatively minor character introduced to pass through the life of Orvil Red Feather, the putative hero of both Tommy Orange’s first novel There, There, and this second one. Near the end of There, There Orvil is shot. This novel goes both backwards and forwards in time and the history of the people around him, and with whom he has biological or chosen relationship (Sean being of the latter type). As Orvil realises when he is told he can influence his future by gaining a ‘better education’, the truth is ‘how much the past fucked with the future’.[3] One of the bullets that shot him left a ‘a hole’ (a star-shaped wound) that he felt stayed open, ‘asking something of me in return, like it needed to be filled’.[4] In choosing a history to place this shooting in context, Orange feels he must rewrite the history of the making of the Native American as a category of identity that had been unneeded when there was no white other to define them.

Starting with Jude Star, this history involves the stories Jude tries to tell his son, Charles, the stories told to him by his father of the ‘Cheyenne people first coming from a hole in the ground’. The stories are fragmentary for there are holes in Jude’s memory, as in the record of the Native Americans after white settlement, but in one memory he recalls ‘our people came from the stars – that big hole up there that empties all its days and nights on top of everyone like the weather’. [5]

That vacant hole in the skies out of which all experiences descends might be what we all want protection from by looking for shelter in categories of self and other. The metaphor about Cheyenne Native Americans we encountered in Jude’s retold stories is also used to explain, in relation to Sean’s identity, the purpose of categories of human specific definition as an umbrella of which the ‘+’ in ‘LGBTQIA+’ acronym is an ‘ever-widening’ one:

… meant to cover as many people as possible from the inevitable rain made to soak the minds of those lost to a system of definitions that increasingly did not include them(.)[6]

Even a taste of those quotations will show that Tommy Orange writes a prose of great finesse that is as inventive in extended and harmonic metaphor as it is ambitious in its scope as story and as a means of understanding its characters, and the self-understanding in its characters’ own reflections. Some metaphors are monumentally important and frequent, though they don’t call attention to themselves (for I don’t find them in the reviews) until noticed. These include two that I single out in my title: ‘stars’ and ‘holes’, and both often come into relation to each other but with no fixed set of meanings or even layers of allegory. We will make mistakes if we try to allegorise these metaphors, except in their immediate context within the novel. Take this for instance from Yagnishsing Dawoor in The Guardian, who says of Jude Star: ‘He learns to read and write in English by memorising verses from the Bible, including one about false prophets – the corrupt and doomed “wandering stars” of the book’s title’.[7]

Such a statement has too much force. Dawoor is referring to the moment in Jude’s story where he looked for a ‘white’ name to replace that of his Native identity. Jude he takes from the Book of Jude, and though he quotes from Jude, Chapter 1 to talk of how he found his second name ‘Star’ he does not choose to wrote the requisite verse of the chapter, though he refers to it as the ‘next verse’ to the one he does quote, ‘that verse about wandering stars’.[8] There is a reason for that, The quoted verse (Jude, Chapter 1, verse 12) uses fantastic metaphors express the sense of purposelessness and dispossession of the ‘false prophets’ denominated in the verse as ‘clouds without rain. Blown along by the wind; autumn trees, without fruit and uprooted’. Had he quoted verse 13 (the one on ‘wandering stars’) the rabid hatred of the writer would be clearer in this blaming of false prophets for all the wrong in the world and calling down punishment on them:

13 Raging waves of the sea, foaming out their own shame; wandering stars, to whom is reserved the blackness of darkness for ever.

The Bible is a wonderful source for metaphors that blame the rootless and dispossessed for their own rootlessness and dispossession. It is a tool of oppression that Jude Star dare not bring full attention to (akin to taking a role standing over other Native Americans and ensuring their compliance to White regulation). The Bible becomes to become a symbol of white CONTROL, ORDER and the agent of policing both, until he discovers that white control meant the eradication of all practices associated with Native American culture.

I’d been promoted to chief of police. I liked that role. It felt to me like it’d felt when we were guarding ourselves high up on its prison-castle walls, carrying a gun and looking down at the interior of the castle, making sure everything went as it was supposed to go. Control, It was needed all along. Order. The trouble came when we were told by the agents that we would be stopping any and all Indian ceremonies and rituals.[9]

All retribution is potioned out to ‘wandering stars’ here, those false prophets referred to by Dawoor as the rationale for the title. But this book is not Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, where false prophets are characters like Archimago and Duessa, and figure out variously both biblical Types , like the Beast and The Whore of Babylon, as well as variously real historical figures, the Pope and Mary Queen of Scots and must be defeated by Una and the Red-Cross-Knight working in union (the Protestant Church truly Catholic and England fully armed in truth and chivalry). It is even more knowledgeable about the phrase the ‘wandering stars’ before it became reduced in Jude to meaning only false prophets. Here is an explanation from a Biblical Hermeneutics webpage:

The Greek word behind the English ‘wandering star’ is planetes (πλανῆται) which is the word, both ancient and modern, for the heavenly bodies which behave other than the stars, their course being very perplexing until it becomes evident that they are circling the sun.

Their orientation is not fixed in the heavens, nor fixed according to the earth. They wander and they circle a ball of fire. The allusion is inescapable. And this is the description that Jude applies to certain people. He thus comments upon their unearthly behaviour and their inescapable destiny.[10]

That wandering stars were misunderstood in pre-Copernican astronomy matters. The planets they refer to do not wander; this is an illusion of relative motion over vast distances of space-time. And Orange uses his character Jude referring to the Biblical Jude with full knowledge of this. Look at this derivation of word gleaned from a TV programme Planet Earth as Orvil make up their sexless but not loveless all-male household, bound by love but also oblivion sought through drugs.

The aim of the documentary seemed to be to show humanity as animal, as organism, and essentially part of the superorganism that was earth. The narrator said the word planet, which is the same word in German, comes from the Greek meaning wandering star. He said we don’t live on a planet, we are the planet, it made us.

Planets are, that is, not sinful and deliberately evil, and neither, at root, are human animals: indeed the latter are unexceptional: ‘never anything more than animals, doing anything more than amimaling’.[11]

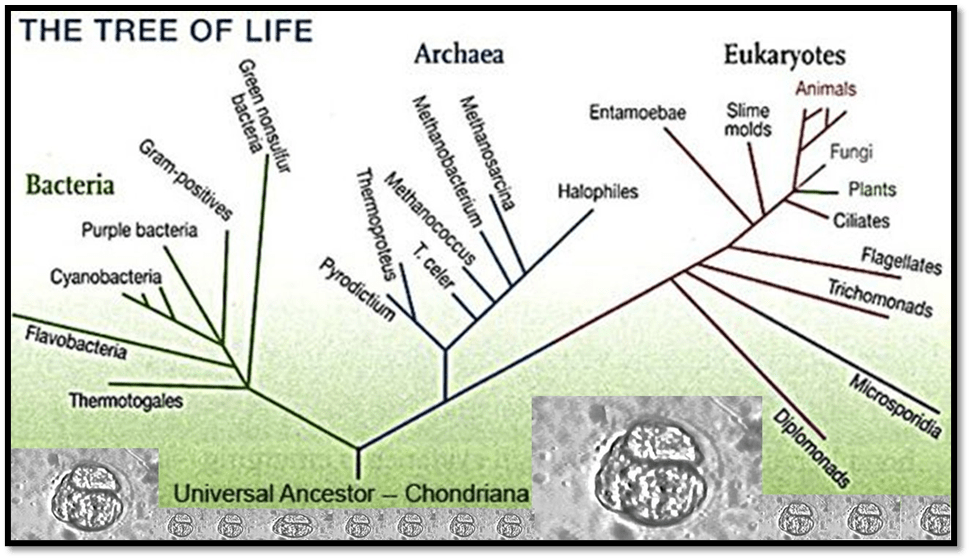

We are all wandering stars, or less significant than that, the primeval mud and slime of creation, since, as Orvil and Lony learn together that, if you take time-space back far enough the fact that we all ‘used to be something else’ (All from Asia or Africa or all, further back, from apes, and further still ‘single-cell organisms’) below (or beyond if you want to vary the hierarchies implicit in language) human distinctions of category (class, race, and so on) mean we were all once just organic slime. Lony Red Feather, talking to his mother Jacquie who abandoned him as a child and has returned to get clean, about what he thinks might be possible about life, where ‘everything used to be something else’:

Did you know seventy-five percent of the time there has been life on earth, it was slime, so everyone, so everyone is just slime then, basically, by the same logic?[12]

If life is accidental and contingent in its ‘evolution’ (a very loaded word used to create hierarchies of being even amongst human beings with each other that justified colonialism and appropriation of the lands of lower orders of being historically) then ‘wandering stars’ are not ethical monsters. More sinned against not sinning, only arrogant power and authority dubs them as ‘wandering’ ethically and doomed to eternal punishment as does Jude. And this is the situation of the Native Americans, and others besides Native Americans including the absorbed degree of Native American of the many not the few shown by blood data: it is like Sean Price, for instance. We know that to be how Orange refers to ‘wandering stars’ for they inhabit the whole novel and shift as meaning and metaphoric reference. That is true of persons (the progenitor Star family for instance) and shapes o volumetric phenomena in the world (the star-shaped hole made by the bullet Orvil’s takes into his body and viscera) that must be interpreted. Holes are implicit in creation and destruction stories. In the final chapter Lony, the last run-away, who thinks himself not a run-away but chased by Fate like Orestes, sees a hole opening that matches the destructiveness of white imperialist and capitalist selfishness intent on destroying otherness that challenges it:

If only the young survive the selfishness of this dying world, of old whites who always thought they owned the earth, to use and expend whatever they can grasp with their cold dead hands, who’ve always led this country down its hole, to its inevitable collapse. We who inherit the mess, this loss, this deficit, this is my prayer for forgiveness, we the inheritors of a world abandoned.[13]

This forgiveness extends to Jacquie too whose world was a hole before she abandoned her sons to it. Maybe, it extends to white America too, though that surely cannot include MAGA ideologies. But even holes are not negative. Physics attributes destruction and creation to the activity at black holes in the universe, not so far from the stories of the creation of the Cheyenne from a hole or a restitution of a world at the bottom of the sea into which a mythical bird dives.[14]

When I read a novel of this magnitude of ambition, I wonder whether we are in the best or even an optimal space in contemporary culture to read it as it should be read to yield definitive good. At its centre are holes that desire filling but the holes are the meaning – the gaps and distances between wish and reality, future fantasy and the felt constraints of a past that has congealed in a harmful way. Those gaps are filled with a needs and hunger to be filled, with food, alcohol, drugs or addictive behaviour (even running – or running away – with some form of recognisable identity that others validate. Sean and Orvil call the drug Sean’s pharmacist outlaw father calls Blanx (a blank indeed), which might be an ‘upper’ or ‘downer’, so contingent is its making on the resources of an immediate present. This is in part the meaning Orvil thinks his healed, but otherwise imaginatively present, hungry and raw bullet-holes suggest to him: it yearns to filled with meaning, any meaning of whatever quality. To read we have to be prepared to live in holes and gaps, knowing the uncanny fearsomeness of so doing but seeing too the creativity they prompt, when answers to felt deficits are uncertain at best, or seem entirely imaginary because not experienced before. I think Wandering Stars goes in directions There, There does not, and that wonderful debut novel (I mention it in passing in an earlier blog at this link).

Partly I think this explains the excursion into the realms of the queer ally of the arguments about intersectional reality in the formation of identities, between people and within each person. It is an adventure prompted by the close links in the writing of this novel by Orange and Kaveh Akbar, a queer non-binary bisexual poet of Iranian parentage, in writing his debut novel Martyr of 2024 likewise (see my blog on this at this link). In his Acknowledgements Orange thanks Akbar, ‘for having written his novel alongside mine starting in 2019, for trading pages the whole impossible way through and for all the immeasurable brilliance you give to this world’. Both approach the world through recovery from desperate hunger for drugs and alcohol or other things, from a hole that is noy yet filled. Lony literally CUTS himself to release internal endorphins, get high on making holes and deep-cut lines on the skin, in the belief that they Cheyenne are literally a ‘Cut People’. His brother Loother (the one who becomes a writer like Orange) ‘lifts Lony’s shirt up and sees how many cuts he has on his arm’.[15] And meanwhile, Lony digs a hole in the earth to bury his released blood, and its ambiguous blood data though to bespeak racial mix. There are other names for such holes. Charles Star, Jude’s son. Thinks of it as a place somewhere wherein he is abandoned and lost, ‘somewhere he couldn’t find his way back from’. But it isn’t only an external space, just as holes confuse the relationship of insides and outsides, and other supposedly fixed categories like biological sex:

He felt something bulging in him. He felt pregnant with death.

And so tired of enduring.

The wolf was still following him. That wicked dog of need inside.[16]

The dog space (god-space since d-o-g and g-o-d are the literal reversal of each other) is filled for Charles with ‘laudanum tincture, that alcohol and morphine mixture’, the drug of choice of the period and of the cusp of legitimate prescription, just as Orvil starts on drugs as he transitions from using them medically as pain-killers. Opal eats her emptiness away by food but eating is a metaphor for the hole inside throughout the novel into which characters pour external consolation, physical, spiritual or behavioural. This notion lives best in the opening of the novel where Jude, not yet Jude but, as he remembers it ‘someone else, someone I once knew’ for this is before the defeat more properly called the Sand Creek Massacre, which we know because of an epigram from the novel from Theodore Roosevelt, he ‘in spite of certain objectionable details’, called ‘as righteous and beneficial a deed as ever took place on the frontier’.[17] For, indeed of such things were the progression of the white imperialist and colonial-settlers made, as they are being made in Gaza now.

Native American deer hide painting of the Sand Creek massacre, a narrative focal point of ‘Wandering Stars’. Photograph: Akademie/Alamy. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/20/wandering-stars-by-tommy-orange-review-wounds-of-history

Survivors of Sand Creek in 1864, as retold in this novel, are left to live or starve in a way that they think it ‘would be better dying than this, the boy seemed to say about our hunger, rubbing his stomach’. The boy and not-yet-Jude contemplate to what level they will go in order to eat what previously they thought of as companions of work and home; A horse, its new-born foal, a dog even filling the space created by the internal dog-wolf. Instead fired at by bullets from men so cold they are blue, they hide under a blanket.[18] However, boy and man carry on but ‘saw and ate many strange things going around together looking for our people, looking for a place we could stay’.[19]

In Opal, Orvil’s grandmother and childhood carer, that hole-space is a wide liminal ‘gray area’. She too has a hole let into her skin, a ‘port in my arm’, to allow in chemotherapy drugs for her cancer stronger than any she took voluntarily ever in her life. Sitting alone in an empty hospital room where she ‘could do nothing but sit’, she begins to call this space the ‘Gray Area’.

The stuff felt more like deletion than depletion. Like a part of me was being permanently erased or replace with gray gray gray, grayness. …. The days did not pass but cracked open, then fizzled out into nothingness, and the nothingness was me, just as the endless gray was e. I was the Gray Area. Between the living and the dead, drifting and shrinking like a cloud.

It’s a hole by any other name, ‘an emptiness that blew me up like a balloon’.[20] I said earlier that we may not be ready for such novels, for even admiring reviews seem over-breezy about understanding its approach to the telling of a history full of deliberately made holes of deletion and depletion as Native American Indian history and hence, life-stories, are. Take Anthony Cummins in The Observer, who says:

Tommy Orange, a Californian of Cheyenne and Arapaho descent, has previously spoken of his desire to write fiction about Native Americans living in the here and now, not a romanticised past. As one character in his new novel has it: “Everyone only thinks we’re from the past, but then we’re here, but they don’t know we’re still here, so… it’s like we’re in the future. Like time travellers would feel.”

You might think from that that Orange is determined just to tell the story straight, as he does in his necessary Introduction to the novel. It does not register that Orange must tell a story with its gaps, deletions and holes acknowledged. Cummins does cite Orange at his theorised best, telling us, here:

… Orange lets his book’s ethical imperative be stated more or less baldly when one of his characters thinks: “It would be nice if the rest of the country understood that not all of us have our culture or language intact directly because of what happened to our people, how we were systematically wiped out from the outside in and then the inside out, and consistently dehumanised and misrepresented in the media and in educational institutions.” [21]

But it is one thing to quote this as if it were the stuff of a didactic novel and another that writes art that enables us to feel what life is like within the holes of the pretended-to-be-unperceived or unrecorded of the history of Native Americans, and to show the horror of its deliberation, not just in Roosevelt but in the tremendously crafted portrayal of Richard Henry Pratt, who ran the reformatory school based on the prison-castle but building its structures inside out from the subjectivities of reformed ‘Indians’: people now with names that will not insult white decorum or rationality, so he thinks.

Yagnishsing Dawoor describes the achievement in creating Pratt well, as in these partial quotations from their critique:

Orange excoriates Lt Richard Henry Pratt’s “campaign-style slogan directed at the Indian problem”, “Kill the Indian, Save the Man”, tracing its ruinous implications for Native children who, in the 19th and 20th centuries, were impelled to attend special off‑reservation boarding schools in a philosophy of forced assimilation. / … Fittingly, the historical Pratt is a character accorded flesh as well as the complexity of psychology. In moments of chilling insight, Orange allows the reader to grasp how it was possible for the man to see himself as well intentioned while being undeniably monstrous.

Dawoor also gets nearer to the difficult feel of the novel, for its brilliance is in part a kill and craft in conveying vast swathes of empty time-space, like the time-space of oppression and ‘addiction’. The characters, Dawoor says, with some brilliant description that I italicise:

… move ploddingly through their days, hyperaware of hauling their familial history. Lony has nightmares of being crushed by it, all that his ancestors “couldn’t carry, couldn’t resolve, couldn’t figure out, with all their weight” knocking him down. Orange replicates these feelings by filling the narrative with a glut of circular dead time. “Every day is a loop … Every day is the sun rising, and the sun going down, and the sleep we must sleep … Every day is life convincing us it’s not a loop.” It’s a risk for a writer to use inertia in this way, but it becomes a refreshing provocation against the very notion of progress: personal, intergenerational, historical.[22]

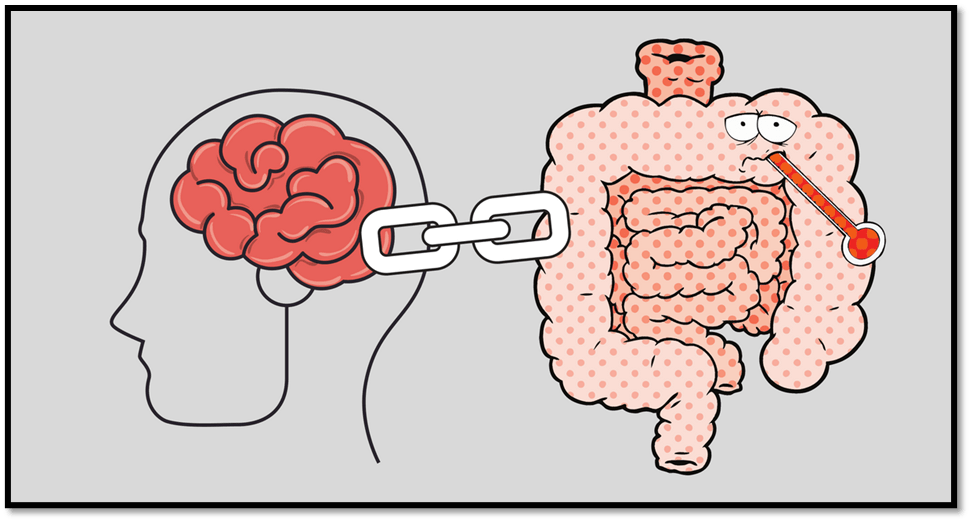

In There There, there are lots of hints that Tommy Orange has made a study of how issues like memory and history interact in individual and group psychological phenomena, as in Edwin Black’s reflections on the role of the hippocampus. His sense of the complexity of that is played out when he invokes the truths of neurotransmission that link active and passive brain operations with gut operations, often ruled by the same neurotransmitter, serotonin.

See https://www.enago.com/academy/the-brain-gut-connection/ for more.

Why are feelings of happiness, wellbeing and fullness linked? This is a question that goes even deeper in Wandering Stars.[23] And, as people look out to seek and find ‘their people’ to fulfil their lives in some ways in both novel, my own good feelings about the latter one is not that anyone ever does or can find their ‘own people’ in it but that Sean finds a way of defining what love might mean for our age, though he does so very obscurely and vaguely, discounting any category he can’t get his head around, like the potential of how he and Orvil could express their love, as they thinks about it after it is no longer possible. But surely this is writing of a very high order of psychosocial understanding as well as well as style:

How could I have expected to just never see Orvil again when we’d become so close I thought we loved each other? … Obviously I didn’t see it coming, but I also hadn’t been living in a way that I foresaw anything or was planning for anything more than getting high and selling more drugs to keep getting high and telling myself I didn’t need school or a future if this kind f now I could keep getting could keep feeling this good. Of course that wasn’t true. I know now. For someone like me, when you find a thing that gets you off, not like sexually, though it’s not that for some people, but if you find a thing that feeds you in that other way that has nothing to do with food or eating but in this way like you could never be full enough of it, well then that’s it for a while, until you can’t get it anymore for reasons outside your control, or you die, basically.[24]

If that is not prose that has felt the pulse of modernity – that makes James Joyce in Ulysses seem over-formal, then I admit I do not know what great modern prose does to reinvent the lament and elegy of the human condition, with its hopes, fears, achievement and disappointment all messed up in a loop of time. And, though I have few talents, I think one of them is hearing such music in writing.

Do please read this book, if you can. It may turn out to not be for you. Discuss it with me. I am addicted to learning – I feel as empty as a black hole without it.

All love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Jonathan Escoffery (2024) ‘Tommy Orange’s There There Sequel Is a Towering Achievement’ in The New York Times (Feb. 26, 2024) Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/26/books/review/tommy-orange-wandering-stars.html

[2] Tommy Orange (2024: 130-132) Wandering Stars London, Harvill Secker.

[3] Ibid: 169

[4] Ibid: 168

[5] Ibid: 35

[6] Ibid: 132

[7] Yagnishsing Dawoor (2024) ‘Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange review – wounds of history’ in The Guardian (Wed 20 Mar 2024 07.30 GMT). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/20/wandering-stars-by-tommy-orange-review-wounds-of-history

[8] Tommy Orange (2024), op.cit: 21

[9] Ibid: 33

[10] https://hermeneutics.stackexchange.com/questions/30551/what-does-wandering-stars-mean-in-jude-113

[11] Tommy Orange (2024) op.cit: 251f.

[12] Ibid: 264

[13] Ibid: 314

[14] Ibid: 35

[15] Ibid: 225

[16] Ibid: 71

[17] Ibid: ix

[18] Ibid: 7 – 9

[19] Ibid: 11

[20] Ibid: 246f.

[21] Anthony Cummins (2024) ‘Wandering Stars by Tommy Orange review – tapestry of colonial trauma is harrowing yet healing’ in The Observer (Sun 24 Mar 2024 17.30 GMT) https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/24/wandering-stars-by-tommy-orange-review-tapestry-of-colonial-trauma-is-harrowing-yet-healing

[22] Yagnishsing Dawoor, op.cit.

[23] Tommy Orange (2019 Vintage edition: 67, originally published 2018) There There London, Vintage.

[24] Tommy Orange (2024) op.cit: 277

6 thoughts on “The holes in Tommy Orange. The author’s account of multiple contemporary Native American life-stories across time-and-space. This is a blog on the massive over-significance of Tommy Orange (2024) ‘Wandering Stars’.”