Sophie Teasdale’s Backstage Worlds: Picturing the Times, Space, and Sex/gender Practices of Public Performance. A show of photographs at Bishop Auckland Town Hall seen on Tuesday 9th April 2024.

Sophie Teasdale’s book Dressing Room No. 1 (it can be purchased at this link as I did) preceded this exhibition which was commissioned by the Bishop Auckland Town Hall’s curators when they saw a copy of the book and imagined a show built around large versions of its images that also commemorated a daughter of the town.

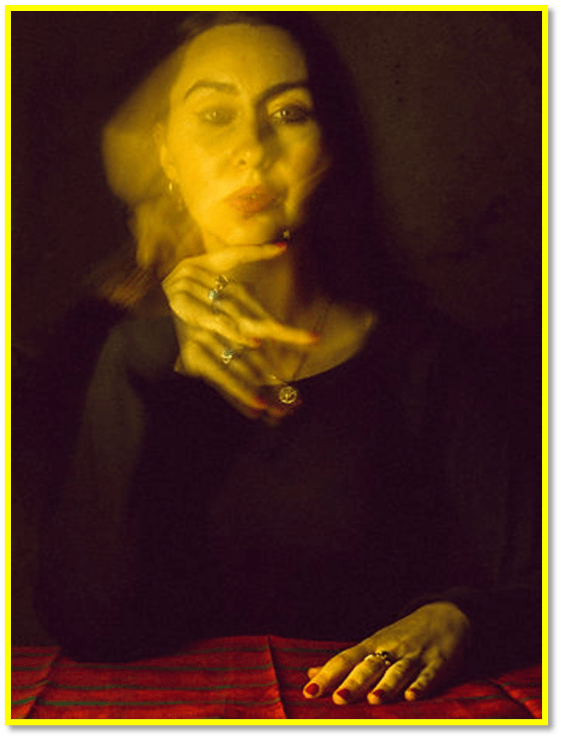

Sophie Teasdale’s career has, having included stage management in its arc, become that of a photographer. She specifically calls herself a theatre photographer and videographer. The plaque welcoming one to the exhibition is reproduced below but it isn’t my intention here to reflect on the ‘fascinating characters’ that Teasdale met and photographed. Most are immediately recognisable but I don’t intend here to use their names. Instead I want to think about what the photographs might suggest to us had we no knowledge of the characters or distinctions of fame and renown between the persons we see. After all theatre, photography and video have always been spaces with detachable products associated with illusion and on the cusp of comparisons of truth and fiction, representation of reality and non-representational fantasy, and artifice called out to find a deeper or hidden aspect of what is natural. Her webpage photograph shows her playing with double exposure to enhance the meanings of her own self-portrait in which even duplicity seems suggested – something of the supernatural and / or uncanny.

Sometimes it is difficult not to name these photographs by the sitter’s name, and more so when the personality has bevome something much more than a practitioner of art in my mind or when it is unclear why they in particular might be occupying a space backstage or in a dressing room. Perhaps that is because we are so accustomed to thinking of those persons as characters who are not thought of as inhabiting spaces prior to public performance, usually in the role of another person, from history or fiction. I will mention one name where the struggle was most difficult in order to illustrate this point: the name is Ken Loach.

But let’s just get into the exhibition first and define its space. You walk through the Town Hall café with its incredibly friendly staff and that permanent exhibition of local art, including some most beautiful Tom McGinness samples, to find the plaque for the exhibition at the entrance.

After confronting the plaque explaining the exhibition (text above), you see Ken Loach’s photograph on on the wall extending to the left as you enter from the Town Hall’s main space (I hope the little plan below is a useful orientation:

The first part of the wall looks as below (in the next illustration) and I gazed because I saw that thoughtful attitude of a master of the political in art, whilst still having my gaze entranced backwards to a facsimile dressing-room mockup built in the middle of the space (green in the above plan). It was an excellent defining idea by the curator; a nod to the liminal function of the dressing-room and backstage space as a place of performance too little looked at. It’s a place where the performance shifts between everyday performance of human roles to more flagrant fictions, even if only of confidence in a public self, that may or may not be well-founded.

And that perhaps is where we are in Teasdale’s photograph of Ken Loach. He looks aside with that tired but still engaged attitude of thought, wishing the world were a better place so that his energy might go into some way of living in it rather than merely critiquing the savagery of present life. But how can he? Cathy still is not home. Daniel Blake is still present, and gig economy workers are still sorry they missed you. It might be fun at The Royal Oak in Easington if it weren’t that locals blame immigrants for the sins of capitalism. Yet in a green-room space, Loach must be aware of how long he has performed as the British state’s, and the Labour Party’s, conscience, and been sidelined by them as much as they both dare sideline a man who performs in order to tell the truth rather than performs as they do merely to survive, however patently unjust they become in thus surviving. Those liminal spaces in a dressing-room is where you become the attitude and not just by how you dress or paint your face but the creation of the complexities of the gestures of true authenticity, that have to be enacted too.

Looking at those three huge photographs starting with Ken was were I decided to abandon naming the subjects of the photographs and try to capture for myself the issue of liminality where we make up and dress an attitude to life, with varying distance from ourselves, as we think we might be outside or within our performance of ourselves to a public eye. And everything contributes to that moment of being-in-the-midst of creating that someone we will be, from the direction of our gaze, our mode of sitting or enfolding our body with itself and its environment, or either turning our back or not, whilst still being aware that we are reflected as other in a mirror. We can tire of ourselves trying to look kingly as we compare our habitude to the image that will complement a crown, the only part, as yet, of the king we are about to perform. We need to see Ken not as Ken, whom we wrongly think we know, but as like those other guys – trying to find a way of being in media res of the things that will enable us in the public gae, with varying degrees of confidence with what we start with, or different ways at least of expressing our self-doubt (often ways associated to our perceived age – a difficult mask to ever cast off).

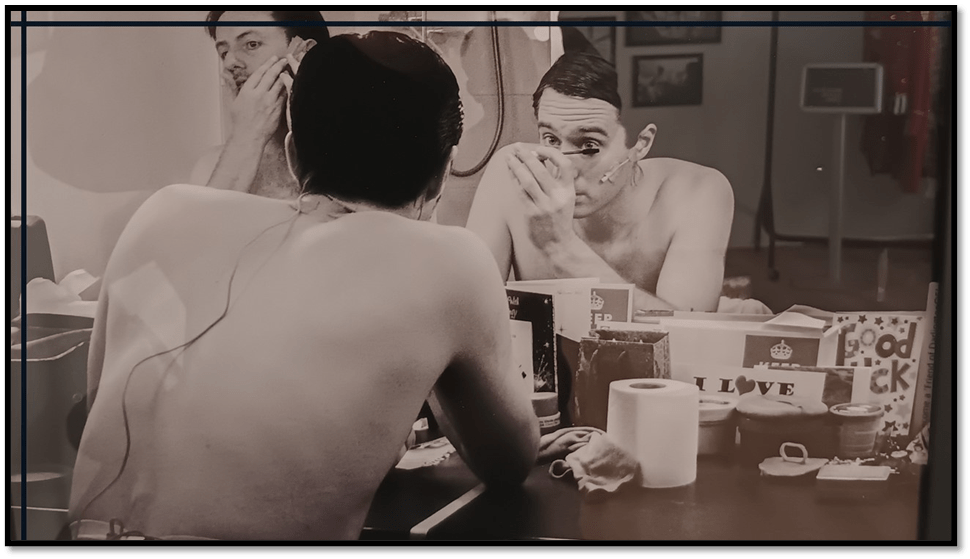

When men are easily recognised, their attitude and look can seem performed at all times, even the nonchalance of looking at our ‘Good Luck’ cards before turning to the mirror. These photographs, even when they capture the most ‘natural’ of attitudes, don’t forget the othering pertinent to an actor’s becoming. The mirror behind the subject doubles it or triples it. But sometimes all we made is the look of another without the mirror, the quizzical look at the viewer or the studious avoidance of them, as if using our pencil to dig out thoughts from within to transfer them to the external page; a metaphor of how an actor becomes the thing they enact.

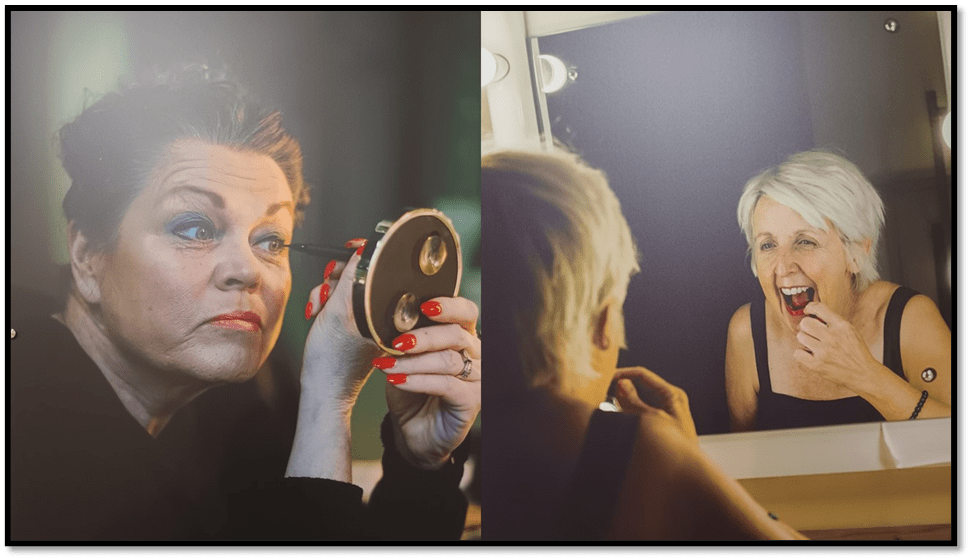

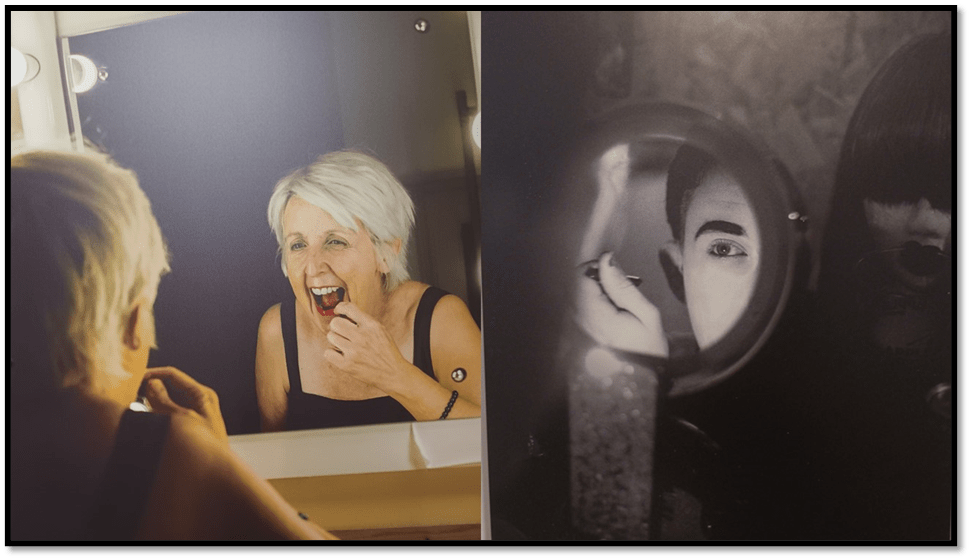

Mirrors and doubles, others and selves are the subject of these photographs, whether the mirror chosen is of the size, and hand-held to boot, to invite more proximity to detail or a fuller part-figure – like the refinement of an eye that looks as if it is looking at you, or in studied unawareness of those looking eyes that gaze on it. In both pictures below sex/gender markers are problematic, where actors enact each the ‘othered’ reflection, perhaps. Because when multiple mirrors reflect each other, the presence of the body is caught in a reflex of images of a they – who may be multiple in one body or several as caught in the mind’s eye. In the pictures above, the first two pictures have a lot in them that performs masculinity, and are like that despite, I think, the genuine beliefs about sex/gender of both of these well-known actors.

In contrast, the one below plays with the markers of masculinity not only in the doubling between two personae but in their distinct attitudes to making up and dressing oneself. In the one that isolates one eye, sex/gender is difficult to determine appropriately, and it is perhaps unnecessary to do so.

There is something, however, about holding a hand-held mirror that feels residually feminine to me, as a boy brought in in the 1950s. The fact that, as you look at the collage below, there is something ‘natural’ (the word comes to mind about the gesture, look and action of the woman on the left) which says a lot about the ideology of sex/gender and the way in which it bends the boundary between artifice and nature, being ‘made-up’ or real around notions of sex/gender. This may have much to do with relative appearance of age or period of look. A ‘compact’, with its mirror is less ubiquitous than in the 1950s – 80s but is de rigueur for a stage actor regardless of sex/gender, where ‘performance’ is not seen as an attempt to be FALSE But make-up as an art always involved the disfiguring poses that the woman on the left of the collage uses, to ensure the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the application, as here, of a lipstick. Yet why does one of these pictures appear to us more ‘natural’ than the other? I think it is partly to do with our reluctance to see that, for a woman, the ‘making-up’ of appearance is an arduous job of work whether used to play a role as your job (as an actor) or be acceptable as a woman ‘who cares for herself and her appearance’. There is no clearer illustration, even in Judith Butler, of the ubiquity of performance as the definition of the interactions of biology and social construction in sex/gender.

Men make up sex/gender differently. Or do they? You would think so in the photograph below, where the male assumes masculinity in clothes, gestures, and conveyed attitude, even in the enforced stiffening of skin. He does it backstage, even before he plays his role onstage. But then, had he been photographed prior to this applying the necessary tone of lip colour, would we have found the performance as easily unambiguous.

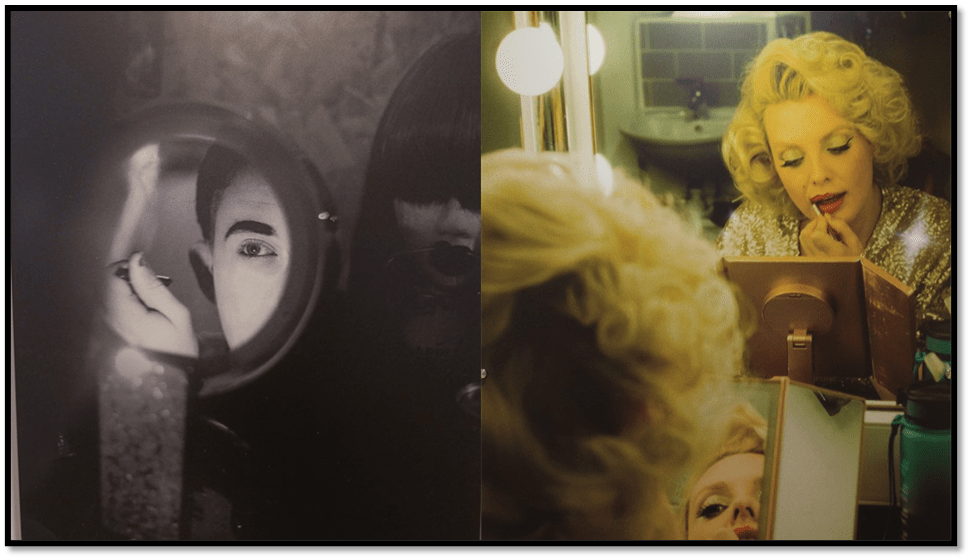

For look again at whole and partial mirrors. They show only the area worked upon, as you see below. Is the figure on the left male, a female playing a male or a male playing the height of coiffured performance of a class image? Does it matter? Yes and no? Ideology rests in our consciousness of such questions.

See each picture next to another, we may see both very differently. Try the experiment below. But mirrors are not just there to double; they are themselves oft gendered markers that sometimes segue into ethical markers around tropes of vanity. Those tropes often bear much ideological weight in sex/gender terms, as in Jane Austen’s Persuasion. There are three images of the person we see as a woman, on the left below, from differing physical perspectives, and only the back view is imaginable as originally three-dimensional. Photographs, however, are another kind of mirror and flatten even that image. The photographer must have been aware that this created the illusion of potentially deepening hole in the back of the sitter’s head as they make up their frontage. Cunning, isn’t it, is photographic art?

What happens when we see masculine markers of multiple kind related to the processes of a ‘made up’ appearance? Look below where there is, I think, deliberative gender-queering of what we are asked to make of what we see. There are three images of what we suppose men in the mirror, though only two belong to the existence in the sitters of one body. Yet it is as if the mirror reflected differing attitudes to being touched on the face, either by a men of himself or each other. Men who frame the well-framed jawline stay ‘more a man’ than those applying an eye-lash brush and straightener. The word ‘tough’ or not comes into play. Yet, what we are seeing is the same performative play that is sex/gender neutral in every which way in fact.

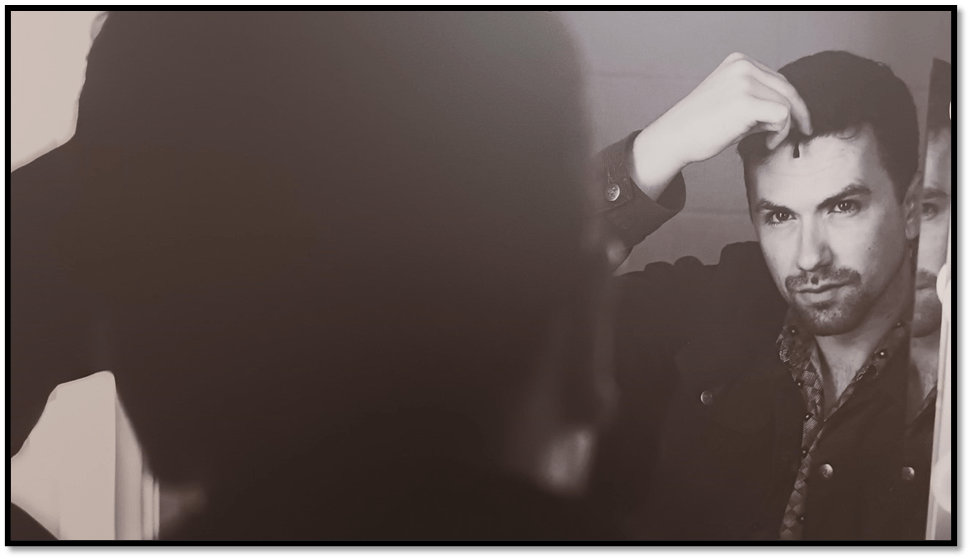

The point is clearer in the comparison below. Whilst the male on the left is allowed to straddle the sex/gender cusp, the one on the right, in appearance anyway, is not. Yet in ‘probable certainty’ both have make-up applied to them by themselves. On the right, however, that performative moment has passed. He has turned from a mirror where it happened and is seen as independent of its aids to duplicity. Ideology wants us to see ‘natural’ man here. But, in part, this is because of the performance of ‘masculine’ gesture and pose (sitting forward and gazing directly to see the other rather than be seen oneself) which is as easy to make up as to apply ‘make-up’.

If we go into that artificial dressing-room in the exhibition, these themes are not only illustrated by smaller photographs outside and inside its walls but the material presence of the actor’s mirrors, repertoire of costumes and wigs which vary the actor’s performance around fictive manipulations of role, including sex/gender but also class, date of historical time or geographical place in space. It is all work as the ironing board and iron remind us. Brushes are unisex, as much as they appear not be to ideologically framed as such. In the room a sound-systems plays tapes of prompts and cues to the actors to leave for their onstage roles. I just appear in the left-hand mirror taking this photograph.

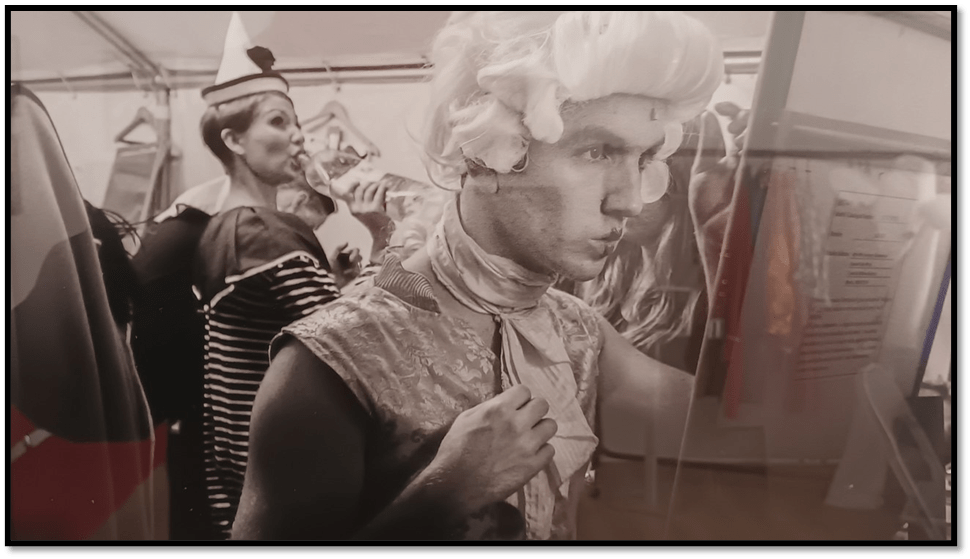

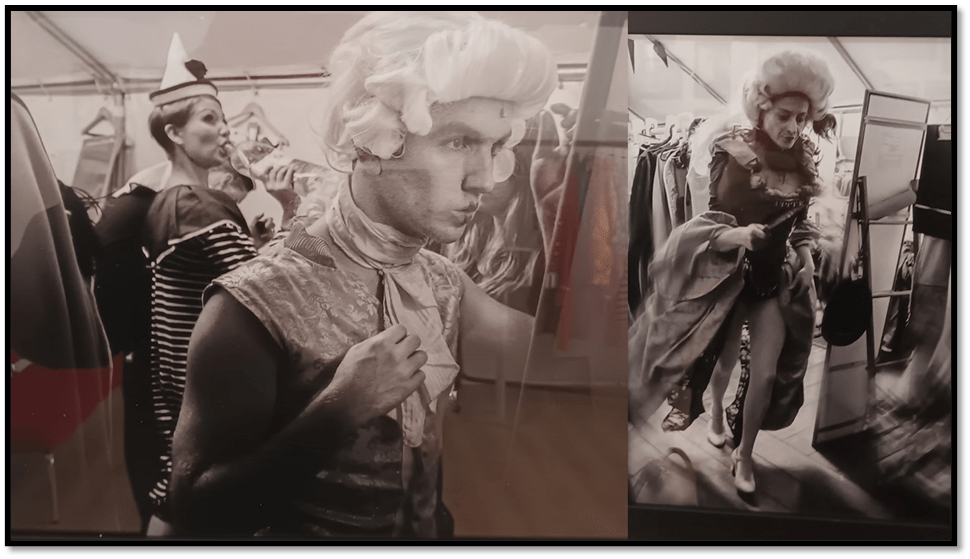

And below wig and costume are a performative prompt to an actor’s manipulations of self by time and space markers. Is this a French aristocrat or an eighteenth-century London beau making up or a play with sex and gender? Clowns or Pierrots can lose these markers altogether as much as we try to recreate them. However, examine the actor on the right.

The self-examination of their make-up ensures facial distortions that ideology associates with women, not men. Yet for an actor, they are necessary whatever their everyday role. But if we also examine the follow-up photograph on the left below, the onstage character – here rushing to become emergent in a role is clearly meant to appear a woman, though not a contemporary one.

But if the play were Charley’s Aunt, what then?

Penley as Charley’s Aunt, as drawn by Alfred Bryan

And men don’t need to be preparing for a female role to feel the liminal nature of dressing rooms. When I was a boy, men who fussed with their hair, other than to straighten it with a comb, were labelled sissy, pansy or otherwise ‘feminised’. Now it is de rigueur, even in your rearview mirror in a car. Yet, the most manly look has been manufactured by some kind of fuss, surely.

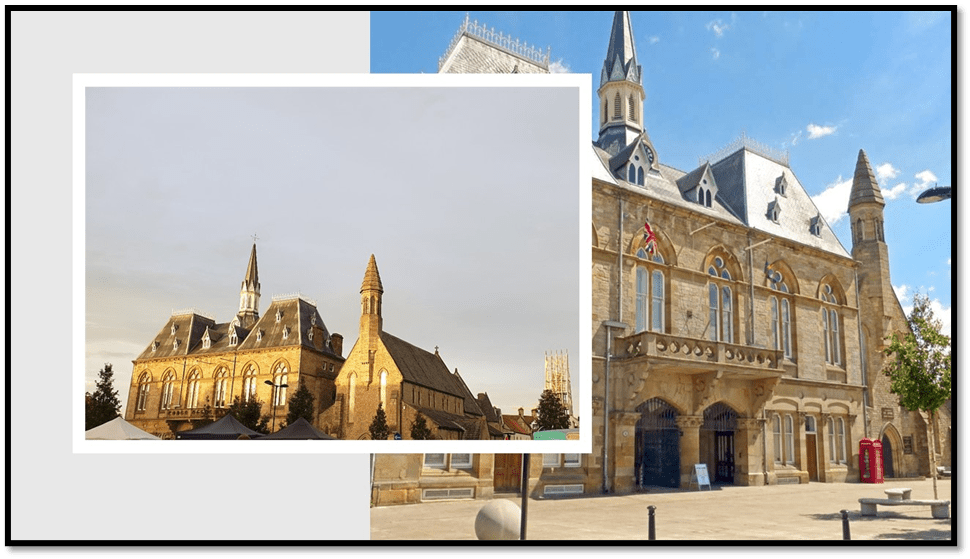

This exhibition may not bring you to Bishop Auckland, but I don’t see why not. Come on Wednesday to Sunday, and you see the Bishop’s Castle, the Faith Museum, The Mining Art Gallery, and the Spanish Gallery, too – though the latter at a cost unlike the free Town Hall. Blink, as you walk through the ugliness that the Tories have made Bishop Auckland Town Centre into, but do love the Town Hall, just as I do:

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

One thought on “Sophie Teasdale’s Backstage Worlds: Picturing the Times, Space, and Sex/gender Practices of Public Performance. A show of photographs at Bishop Auckland Town Hall seen on Tuesday 9th April 2024.”