‘Kwame had slept with more than thirty men, and he reflected again on the fact that only three of them had been Black. … reciprocating didn’t come easily. He was always tentative, because, with each of these three Black men, as distinct and variable and beautiful as those encounters had been, with each there had been a moment – a shuddering and shaky moment – when Kwame had felt too seen’.[1] This is a blog on intersectional nuance and Black queer sexuality focusing on Michael Donkor (2024) Grow Where They Fall Fig Tree, Penguin Books.

There is a lot that is tentative and lot of ‘shuddering and shaky’ moments in Michael Donkor’s latest novel, though not all relate to the ways in which queer relationships between Black men are experienced as differing from those between Black and white men. Michael Donkor’s latest novel doesn’t altogether ever allow us to feel that its protagonist, Kwame, is at all a test case for understanding how any other queer Black men experience such relationships. Kwame is I would say too distinct a character to generalise from his experience in any way, though there is something universal about his experience.

In the end this novel is another Bildungsroman – a novel of ‘education’ and /or developmental formation of a person – like Goethe’s Wilhem Meister or Dickens’ David Copperfield, bone based on how a transplanted seed might grow, development or learn within educational contexts that have aims that are in some ways working to alienate, rather than nurture, that seed, to ‘raise’ or ‘grow it in ways that not only change the way the seed might have grown in a place more clement to its needs climatically and culturally. There is a useful reflective essay on the Black Bildungsroman by Black poet Joy Priest at this link. Had I space I would discuss it.

Nevertheless, though Kit Fan is a good reader and his description of the novel’s structure could not be beaten in so few words: he says its:

episodic, alternating structure is informative, suspenseful but risky. Like cutting a cake into equal halves, the two timelines need to move in tandem, so that the past isn’t just a prop for the present, or vice versa.[2]

But he describes that structure without really taking up the bildung idea as it is implied by both past and present alternate halves concentration on the formative role of education as a giver, receiver to its mixed effects of creating, even in one person, both beneficiaries and victim-survivors of such a process. And the bildung theme is played out in terms of whether Ghanaian families truly and rightly grow in their diaspora or broadcast by a wanton sowing of its seed. Fan puts it thus in his Guardian review of the novel:

‘Our People. Scattered to your four winds … They land, but do they grow where they fall?” This “half-dreamy, half-sad” question, addressed by a Ghanaian father to his son Kwame, haunts Michael Donkor’s second novel. It casts doubt on the promised land of dream and opportunity that drives so many diasporic narratives: one where first-generation immigrants sweat and save, so that the second generation enjoys a better education and life.

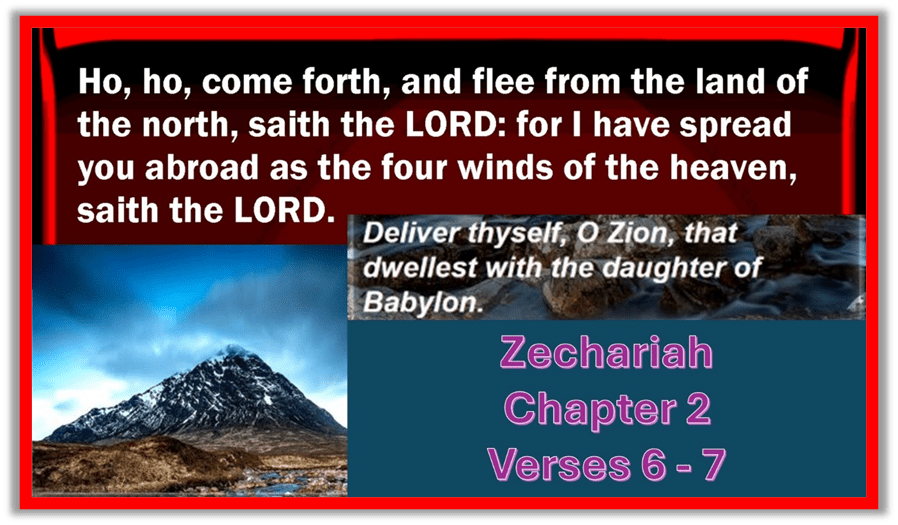

The idea of the ‘scattered’ and ‘fallen’ does a lot of work here and Fan could have said more here, This because I think there is no hint given in the novel that the UK was ever believed in as a ‘ promised land of dream and opportunity’ for long and the language here leans back to earlier narratives of diaspora, even of contemporary migrations, where ‘scattering’ is to places no better than Babylon itself for the Jews to which the submerged quotation in that cited by Fan here refers in Zechariah Chapter 2, verse 6-7 : ‘“6 Up, up! Flee from the land of the north,” says the Lord; “for I have spread you abroad like the four winds of heaven,” says the Lord. 7 “Up, Zion! Escape, you who dwell with the daughter of Babylon”’.[3]

Seeds fall as they are broadcast, but do they ‘grow’ and developed in that soil of acculturation, building, formation, and education. This is why so much of the novel is about the potential to mis-educate and to alienate; to form relationships in which what is learnt is deformative not formative, about what withers shoots rather than grows them to their promised ends.

Seeds that fall are like gods and angels that fall too and, perhaps, the least satisfactory element of this novel, as Kit Fan thinks too clearly when he says that:

Donkor gives generous – sometimes too generous – space to the young Kwame’s idolisation of Yaw, who “didn’t behave like people were staring at him or acting like he was a god fallen to earth”. [4]

The point Satan and his rebel angels teach themselves in Hell is maintain the very pride that led to their fall, and that is the point of the Yaw who Kwame not only idealises but admires for his well-maintained resistance to the mores and practices of an oppressive land to which he has been imported, only in the novel’s denouement for Kwame to recall the memory of his humiliating deportation as an illegal immigrant. His prompting sin is impregnating the hapless Melodee. Least convincing of Fan’s judgements of the novel is that Donkor’s ‘meticulously observed prose holds back a heartbreaking secret until the final pages’, which is the secret that Yaw would be deported from Britain, for it seems to me this was a deliberately ill-kept secret; revealed late but obvious too as a contributory cause of Kwame’s unsettled feelings about becoming a cog in the educational machine which, even where it succeeds with Black and Brown children, malforms them in their growth and alienates them fro the host community and their past ones.

Yaw’s banishment is as inevitable as Satan’s. He had too much beautiful and promising pride in his own culture. That he is punished for that is part of the fait accompli of a novel about how White Education and opportunities necessarily fail to allow Black children to grow AS Black children and not Black children in a white Mask. Kwame’s father calls Yaw a ‘BLACK FOOL’.[5] However, I think the latter is true of both of the novel’s protagonists, who both are educational successes in a White system, but both are also somewhat malformed: Kwame and Marcus Felix. The question is mainly investigated around the experience of two Black men with differing kinds of mask. Both, that is, approach their self-representation in public space differently but still as defined by a hegemonic White society: Kwame, an almost ascetic, and certainly over-regulated, queer man of Ghanaian parentage and Marcus Felix, the Black headteacher defining his sexuality by experimental advances into a new field of active experience.

Whilst the latter acts, sometimes ineptly, in order to try and define and even develop himself in roles he is given or wants to try out, the former attempts to avoid as much action as possible, at least after he learns what happens to Black boys who play the Artful Dodger to ‘Consider Yourself’ as head of a white troupe, in the hope that he evade definition before an audience (perhaps even his classes). Other people’s gaze, after all, attempts to categorise one in its terms. A beauty of this novel is that it investigates it in terms of Black queer men in media res of their adult and childhood formation.

It might be worth looking first at that way ‘pride’ in self is, as with Yaw, a failure to be self-conscious as a Black man, which leads them to ‘behave like people were staring at’ them ‘or acting as if ‘ they were very unusual, a god fallen amongst us. A lot in this novel is about how people cope in being seen by others, and their anxieties about the mode of that perception. Yaw was deliberately however named, with the irony of his fate as a man who impregnates involved, as well as his masculine pride. Note Wikipedia on the name:

In the Akan culture, day names are known to be derived from deities. Yaw originated from Yawoada the Day of Reproduction. Males named Yaw are known to be courageous and aggressive in a warlike manner (preko).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yaw_(name)

That young Black men are subjected to surveillance is made clear by Marcel from flat 333, Yaw’s friend, but the surveillance of young Black men has its analogy to for the middle-class characters that emerge from working-class backgrounds who as young men themselves had bought into ways of passing as acceptable to the police from an early age:

Why didn’t Marcel just speak to the officer politely – perhaps ask how their day was and tell them about his – then they would have realized he was not a menace to society.[6]

It is this skill of appeasement and both ‘whitening’ and up-classing his image that equips Kwame to be ‘standing’ as he does by that ‘whiteboard’ in his class (so appropriately named) representing a “role model he likes of which they won’t have previously encountered” to mainly young Black learners, as Madame Evans, his Headteacher at the novel’s start, says (keen to appear one of ‘the good ones’, that is a white person who is not racist). These whited sepulchres are probably as racist as more overt racists, Kwame feels edgily: he wonders ‘if she would have talked to a white candidate in that same tone, using those same terms?’[7] But we should note the fact that Kwame always questions himself and thinks he might be ‘awful’ in thinking this about Evans. It is as if the worst detriment of racism was this casting of guilt onto the ‘victim’ of racism rather than its white perpetrator, who remains entirely unconscious that they are being racist. This is poor soil in which Black souls can grow and learn as either professionals or, as we shall, lovers who do not reproduce some degrees of racism in the manner of their selection and conduct of relationships to the others.

I will try very hard later to explain why ‘growth’ and ‘development’ are difficult to achieve for people and groups when they hide who they could be under the mask of what other people and these other people’s norms of what one SHOULD be or look as if you are being. I think this is the only way we can understand the description of Kwame’s sexual history that I quote in my title. Here it is again, in full:

Kwame had slept with more than thirty men, and he reflected again on the fact that only three of them had been Black. … reciprocating didn’t come easily. He was always tentative, because, with each of these three Black men, as distinct and variable and beautiful as those encounters had been, with each there had been a moment – a shuddering and shaky moment – when Kwame had felt too seen.[8]

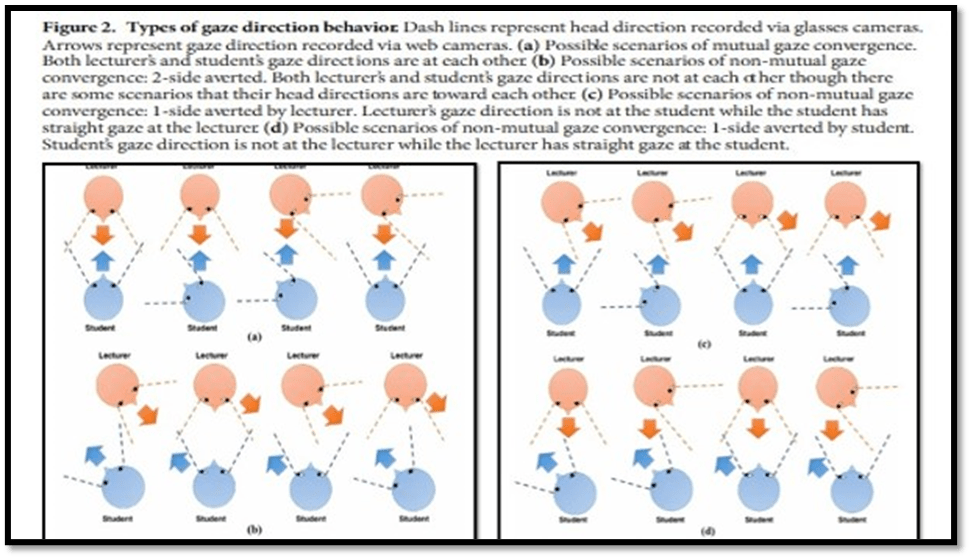

These issues are engaged with around the idea of how much one allows oneself to be ‘seen’ or observed by others. After all, Madame Evans had already told Marcus Felix that Kwame was “one to watch”, though she meant as an exemplary teacher.[9] And the issues of being seen-or-not-as-you-would-like align constantly with internal disturbance of the nervous system, hard to categorise, that are not the settled comfort of being seen as you think you are or might become in development. Questions of what people see in you, or of you, play sensitively under the surface of a prose that does not advertise its subtlety. Racism and homophobia both exist, in their least gross forms in negotiations of how people observe and evaluate each other and make the mutual allowances for the openness that ensure a growth of mutual understanding occurs. In such circumstances only, does the relative thing we call personal growth occur. The finest example of this comes in an almost unnoticeable scene. Here, the queer housemates, Kwame, who is Black, and Edwyn, who is white, stop at a station florist and are observed rather differently by the latter. The white florist and Edwyn build a temporary mutual understanding as they laugh at the antics of a ‘little re-haired girl’ on a scooter, whilst Kwame observes the flowers, sidelined in that drama of mutuality. When Kwame, who ‘had been quiet for a time’ is drawn into the conversation around the choice of flowers for Edwyn to buy, the florist speaks to him in ways that show that he is critical of Kwame’s taste whilst: ‘He did not meet Kwame’s eyes’.

When the florist does look at him he ’eyed Kwame slowly – scanning from head to toe’ but talks not to him but only to Edwyn, encouraging a different selection of flower. The conversation again excludes Kwame as the white men discuss their mother’s tastes leading to a joint agreement. Meanwhile: ‘Momentarily, the florist’s eyes flicked back towards Kwame, seemingly discovering something distasteful, and then flicked away again’. The purchase cemented by florist and Edwyn alone, the goods are noisily wrapped whist the florist finally ‘eyed Kwame again’. This exchange of men observing each other, perhaps even queer men, given the play between florist and Edwyn, disturbs Kwame and disturbs a reader sensitive to the novelistic depiction of mutual gaze scenarios. We cannot analyse nor effectively intervene into what is happening in that exchange for it is not clear that we can be sure anything is happening, for nothing is explicitly said. Thus Kwame reflects:

Was it racism? Was it? Could Kwame let the building adrenalin help him to raise his voice so he spoke without confusion about what he could see? … Did Kwame want to make that mother, …, wince at the sight of an enraged florist demanding Kwame show proof of prejudice? Why should Kwame have to do that – explain what was plainly and painfully there?[10]

The unconfronted racism experienced in a moment of internalised anxiety is what dams growth for Kwame and what I suppose contributes to stopping him exploring and utilising what in his self identifies as Black and Queer, valuing each and their interactions for himself, validated by communities of mutual respectful seeing of each other. It is, I would guess why the novel has to explore why it is that Kwame has engaged, relatively speaking, only minimally in relationships with Black queer men, only three out of 30 men he can remember, now that he has retreated into having sex (with a white man) only out of what he feels to be absolute necessity, were not white men. Kit Fan describes these issues as the:

… cornerstone questions in Kwame’s life. Is it because of Yaw that he is more attracted to white men? What frightens and fascinates him about Marcus? What’s behind his closeness to his teasing, privileged white flatmate?

In a novel exploring sexual abstinence, Donkor writes beautifully about the meaning and meaninglessness of sex. Each erotic moment in the book – swiping Grindr profiles, anonymous hook-ups, friends with benefits, or daydreaming – is described with well-measured excitement and puzzlement. Reflecting on why he’s only slept with three Black men, Kwame feels “a very powerful kind of closeness that came with a sense of loss … a feeling that set him on edge rather than settled him”.[11]

As much as I agree with Fan’s view here, I think it misses the key thematic clue that explicates the ‘cornerstone questions’,and which is that which unsettles Kwame. Moreover, it does so continually as an adult. It is his fear of seeing himself as a Black queer man, rather than a queer man in a supposedly colour-blind manner. Only recognition of the deepest interactions of one’s being (I am resisting the word ‘identity’) allow one to grow, and the same thing applies to Marcus Felix where the question runs deeper and is approached from the view of a Black passing-as-straight married man exploring his sexuality, and also being almost forced to do so with a white man, the ever willing Edwyn.

Moments of seeing and being seen are crucial in the novel, other than those of a Black teacher of mainly Black learners in front of a ‘whiteboard’. Performance is a commanding metaphor of the book and Kwame is often in the spotlight metaphorically or really. Asked as a boy to pronounce a Ghanaian Goddess’ name, ‘Mami-Wata’, correctly by his white teacher (although in fact he was mimicking her), he ‘wished he could have decided when and why the spotlight was shone on him’.[12] Enactment metaphors are first encountered as a series of memories prompted by giving a speech at his thirtieth birthday, where he remembers the ‘last time he had been on stage’ in his childhood at Thrale, a memory we will later see narrated. From the beginning the primary memory of this show is linked to different kinds of performance in the life of adults and children:

He knew standing at the whiteboard everyday was a version of public speaking. But was it ? – family, peers. But it was different when the audience were expectant – quietly judgemental. And so the run-up to his birthday speech had been marked by sickly anticipation.[13]

That feeling of nausea felt within people observed by those with expectations – positive or negative of them – aligns with lots of other inner disturbance that continues under an apparently calm surface in the novel. Indeed the opening is of a boy disturbed by his parents’ raised voices in a quarrel which he attempts to appease by presenting his own calm surface.[14] Teachers and headteachers likewise prepare themselves to be seen, in engaging learners who feel alienated by class and race issues implicit in the teaching process and the developmental model implied by it. These issues are pertinent in school events like Parents Evenings. Donkor makes great play too with persons enacting their Public Roles, whether Madame Evans or Marcus Felix as Headteachers (decent liberal white, or role model Black, Headteacher) creating almost theatrical thematic settings for their respective roles. The key public figures are the ubiquitous (in the twenty-first century school sections of the novel) Behaviour and Progress, the way the ‘Heads’ of those school roles are identified. The regulation of Behaviour and Progress are both essential to development or formation / ‘bildung’ (when I taught the role was just Development and was held by a purely institutionally defined and critically under-developed jobsworth personality).

Donkor laughs at them in his irony like the professional well-behaved teacher he is. ‘Head of Drama’ does something somewhat dramatic and ‘Head of Behaviour’ does something behaviourally appropriate when Headteacher Madame Evans collapses in public, whilst: ‘Head of Progress, his fingers wide and palms assertive, told everyone to move back, back, back – get back! – …’.[15] I have met these progress chasers intent on sending people backwards before myself. Even more amusing is the scene where Marcus Felix, ‘in the distance, flanked by the heads of Behaviour and Progress’, now the headteacher, patronises Kwame as he absorbs himself with the ‘old fogies’ planning how to deal with how the children see the wedding of Prince Harry and Megan Markle regarding the question of race.

Walking through the pergola, each member of the trio had slung a blazer over his left shoulder. The T-Birds had nothing on them. The three examined the packed garden, pointing as if surveying peoples and lands they would soon conquer, Marcus Felix nudged Behaviour in the side, slapped him on the back.[16]

They find a place, Behaviour and Progress, to which Behaviour beckons the head over, whilst Progress struggles with a pub-garden’s ‘Carling parasol’. Kwame’s cool ironic observation of Marcus Felix at this point is superbly accurate of the Black headteacher having given in to a paradigm of normative development that is purely institutionally defined.

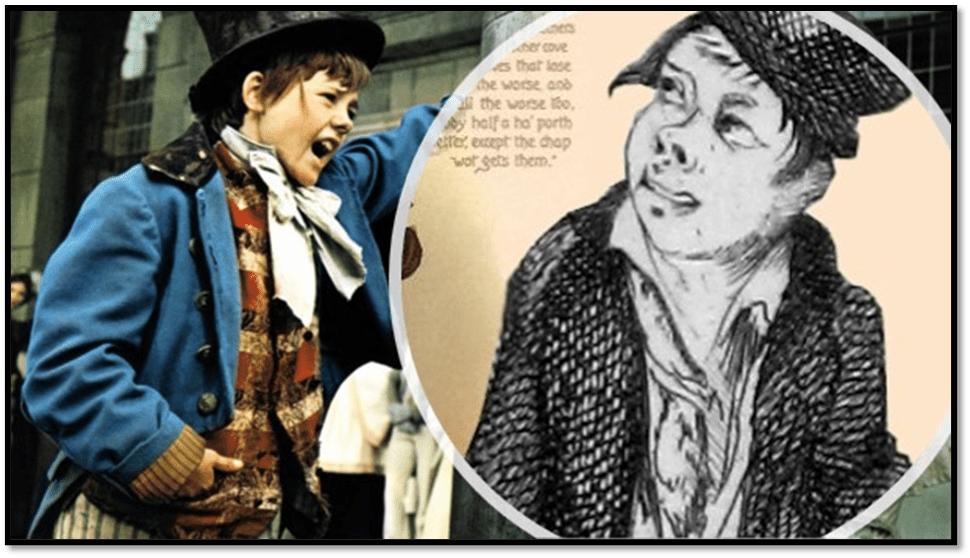

There is a pastiche of drama in all of the above as roles are acted and as often over-acted. And enacting roles is how the sections of the book, interleaved with the adult scenario, dealing with his own schooldays as a pupil in a school where his models are mainly white boys (but for the totally exceptional Yaw in his home). His teachers he thinks prepare him to ‘imagine defeat before he had begun’, and this had proven a self-fulfilling prophecy of a classic kind before the key turning point.[17] This is where, in preparing to audition for a role in the school concert and singing parts from Lionel Bart’s Oliver by both Artful Dodger and Oliver with a ‘show of swapping of roles’, he acts with a confidence aligned to what he has learned of Yaw’s pride in his Ghanaian heritage even by scooting back from the judges ‘snakily, a bit like Yaw’s Moonwalk’.[18]

The inclusion of the art of young Black people rather queers a role most often played for the arty cuteness of its pleasant villainy, but make no mistake, Dodger is artful in the sense of cunning. One of the most painful of the potentially racist interactions in the novel is where the teacher Miss Gilchrist tries to persuade Kwame to play the role of Artful Dodger in ‘Consider Yourself…’ to please the audience my making himself less ‘square’. Looking at Miss Gilchrist and smelling the clean bath towels on her skin he has to remember that: ‘inside her heart most probably the old blood of a white slave master was still beating and he could not think of anything more disgusting’. For, after all, in her proximity and her requests that he be more playful an old trope of th sexualisation of black flesh is being played out.[19]

Success or not as Artful Dodger, the song by Leslie Bricusse ‘Consider Yourself’ is more sinister than Gilchrist presents it as ‘a song about family, about inviting people in, showing them a good time’, though the double entendres in her talk at this point reveal in part her entitled playfulness with black men and boys when they are more vulnerable than she. Just Consider not Yourself but the words of the song for a moment:

Consider yourself at home

Consider yourself one of the family

I've taken to you so strong

It's clear

We're going to get along

Consider yourself well in

Consider yourself part of the furniture

There isn't a lot to spare

Who cares?

Whatever we've got, we share!

If it should chance to be

We should see

Some harder days

Empty-larder days

Why grouse?

Always a chance we'll meet

Somebody to foot the bill

Then the drinks are on the house!

Consider yourself my mate

We don't want to have no fuss

For after some consideration, we can state

Consider yourself

One of us!

Consider yourself

Jolly white japes in which the excluded criminal class include – but definitely white mates only

About family certainly and about welcoming in a stranger the song may in fact be, but its intention in the context (even in the musical) is just to abuse Oliver Twist in the worst possible way, and is an analogue to the situation of Yaw, who is made ‘one of the family’ only to be secreted, employed illegally at low cost and deported when he sows his seed within Melodee.

However, the cruces of the novel are those in which a drama in which each man is observing and being observed by the other is played out by Kwame and Marcus Felix. It starts their vicarious introduction to each other in the novel in a comparison of each enacting a part in a play or public occasion – Kwame in a modest student ‘one-man version of A Streetcar Named Desire’ set in Bethnal Green at Durham University.

A view of St Chad’s College, looking along North Bailey By Vbrown1904 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=146042728

Marcus Felix’s career is played out a lot in the eye of the public media. His appearance strikes both men (himself and Kwame) as an icon of leadership with an ‘imperial quality’ and mature attraction: a ‘bald Black man: convincing forehead; expectant hazel eyes; proud chin’, But however played for appearances, Kwame’s scrutiny determines that Marcus Felix ‘could never be called bullying or brutish’. It is the qualities of a Mills and Boon hero but set in a school. Kwame zooms in on his features and finally ‘zoomed in on the eyes again’.[20] Never has a drama of observation been better set up in a novel.

From: A scientific study of gaze (I am not going there. LOL!) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311356041_Prior_Knowledge_Facilitates_Mutual_Gaze_Convergence_and_Head_Nodding_Synchrony_in_Face-To-face_Communication

Fan points out that there is sexual tension from the first sight of the Head by Kwame: ‘fantasising how “he would sniff and slowly pass his tongue around the headteacher’s armpits”.[21] Kwame observes sweat on Marcus Felix frequently, and sometimes it is the sweat of a more ambiguous invitation – sexual perhaps but nervous and uncertain. The point is that I don’t think Donkor allows us quite to know what the reason for his excitement is perceived by his omniscient narrator and Kwame’s own excited point of view. Perhaps neither need determine from the mix of options a single one. The idea of a head, once already described as of ‘imperial quality’, ‘falling apart’ in Marcus Felix, is I think barely in Kwame’s ken who has sex in the head and for a Black man perhaps for the first time that promises endurance. The passage uses bodily symptoms that betoken all three of their roles in the nervous system: fight, flight or frolic (panting, blood racing and so on):

Marcus Felix patted a seat as breath pounded through him. He dropped his shiny bald head forward and held it in his hands like it was in danger of falling apart. His heaving shoulders, vest and shorts were covered in sweat.[22]

Thus Kwame observes the Head, unaware, I think, of the intensity of the gaze either being returned or given to him by Marcus Felix. Soon markers of mutual gaze have to be acknowledged though they remain ambivalent to reader and characters. Outside the Vauxhall Tavern where mutual gazes are sometimes intent, Kwame thinks: ‘Who winks? Who? Why, with all; the other verbal and non-verbal tools available, had Marcus Felix chosen to wink at him in the staff-room’.[23]

Marcus Felix ‘observes’ (the technical term after all in teaching quality control) Kwame’s teaching method and style. Kwame can ‘feel Marcus Felix’s gaze between his shoulder blades’. The link between professional and sexual evaluation is lively in its presence, but so are other components of the gaze, including powerful dominion of the object of the gaze. Kwame has many reasons therefore to have ‘resisted the urge to turn around and check what those hazel eyes were thinking’.

In many instances in the novel Kwame gets what Marcus Felix is thinking wrong? The interpretation of mutual gaze can be difficult even outside or inside the Vauxhall Tavern. Marcus Felix plays with these ambiguities, asking for more ‘deeper, human connection’ in the teaching observed. We might guess that there is a more coded message here as well, whether consciously or unconsciously so, for Marcus Felix is learning he desires such connection to Kwame himself.[24] And for Kwame, it is easy to see the Headteacher’s especial gaze on him as a threat or a presumption as he does in the Gents toilet thinking back at how Marcus Felix could ‘breezily pry, be so personal’. It’s worse he thinks, because based on them being ‘both Black’.:

Because that was why the headteacher felt able to be so presumptuous and pally, wasn’t it? It was infuriating – completely infuriating – that no-one seemed troubled by Marcus Felix’s intrusiveness, his showiness.[25]

Prying eyes and showy looks illuminate this continuing conflictual drama of mutual interpretation, misinterpretation, partial-interpretation or fear of certain interpretations, such as Marcus has to bear silently, for to Kwame the latter’s arrogance stems too from a showy heteronormativity, one that he does not even question. Nevertheless, Kwame imagines his tongue licking the head’s armpits, with mutual easiness for both in feeling each other’s ‘cock hardening’.[26] For how to perform queer roles is important too and what Kwame fails in seeing is that playing these roles when Black can be different in effect on his development. He senses it in him but yet precisely 90% of the sex he remembers (27/30) is with White men because Black men disturb him as causing him to be ‘too seen’.[27] Both Marcus Felix and Kwame need to be seen across the intersections of identity they occupy and live within uncomfortably if they are to grow where they have fallen.

They scene where they ought to see each other is a scene of mutual delayed or hidden gaze of each other on the early morning run Marcus Felix invites Kwame too, where they watch a fragile butterfly, a psyche indeed, But, watch each other they do:

Turning to his right, he noticed the headteacher’s stare: there was an almost-imperceptible difference to it. Less definition about the corners of his eyes. Kwame felt strange.

How much, Kwame goes on to ponder, is the exchange of gaze ‘probably projection’? Both of course project themselves into the butterfly which ‘kept trying to right itself’. [28] It is a moment where Kwame has himself revisited his own learning about attachment to others at Mount Nod Secondary School:

How carefully he sought acceptance across the board – the skaters, the rude boys, the Asian rude boys, the neeks, girls – getting close enough to all but not so much so that anyone might be able to look at him too much, …

Never quite nurtured because never quite CONSIDERED ‘one of us’ by ANYBODY: ‘making in none of these groups a solid home’.[29] This is an effect of racism but an introjected one. It mars completely his relationships with each black hero he eventually idealises; Yaw and Marcus Felix remain at a distance from him within the each of the two time zones they both appear in. And the things that makes us grow are things we allow to be seen. Kwame over-regulates himself. So, of course, does Marcus Felix who cannot bring himself to fully his explore his sexual liking of men openly, though he hints enough to Kwame (any fool would see it, you’d think). And Kwame is one of the levers, despite himself you might say, projecting his own psychosexual bildung onto Marcus Felix, which ensures that Marcus Felix first realises his queerness with a white man, Edwyn; not a Black man. It certainly is not Kwame who in a kind of voyeuristic happenstance gets to gaze unexpectedly on the scene of his most jealous fantasy. And this is allowed to happen by Kwame despite ‘Marcus Felix’s frequent, sideways glances at Kwame’.[30] Watching Edwyn fellate Marcus Felix whilst standing at Edwyn’s bedroom-door and surprising the couple and himself, Marcus has his own ‘eyes clamped shut’, at first, until Kwame’s eyes suddenly seem to awake Marcus Felix at the moment of his orgasm: his ‘closed eyes flicked open and met Kwame’s, and Kwame watched Marcus Felix struggle for shocked, almost choking breath, …’.[31] And then the sexual ‘climax’.

I think I may have over-explicated above what possibly needed no explication. What stuns in the prose of an otherwise quite traditional novel is a fascination with the roots of anxiety that eat away from the few chances people have to grow by meeting that which they have hidden or repressed; thus limiting their growth and health. It is a novel of deflection and sometimes hiding. Kwame deflects when people get close, even when it is not that close as in his queer white friend’s sharing with him his belief that Kwame deflects intimacy. That is one of the reasons he deflects the conversation, for Edwyn finds rather broad humour whilst ‘limiting awareness of Kwame’s unease’. Kwame always deflects conversations that deflect attention from things that make him nervous by changing the subject or introducing a calmer tone, though it is not one he necessarily feels. He, as it were calms troubled and turbulent waters, though within him they rage still. t make him uneasy. In this case with Edwyn it is openly: “Fuck off, Wyn!’ [32]

In other situations too, as a boy when his parents quarrelled, his somatic control and regulation becomes a metaphor for his control of his inner feelings:

He curled himself tight – chin jammed against his chest – keeping everything still, even though his heart and mind jumped like the stormiest waves.[33]

Often that curl is one that involves the dark of the space under his duvet.[34] As a boy he watered spider plants because it was ‘a job that made him calm and safe’.[35] And as a boy, what gets most repressed are the moments when Kwame feels the world to ‘pulse with a new energy’ with his introduction through Yaw to the fruits of Black culture – the music of Tupac for instance. The very music too associated with Yaw for his parents to be calm about who hear him humming it and:

… shouted, anger no longer containable: how many times had they told him never to bring Yaw’s Tupac music under their roof again?

And Kame too seeks to contain that music and memory of Tupac, as he most successfully does with Marcus Felix, never letting it show so that a relationship never develops as it might have done between them in either case. Thinking of Yaw and disturbed, and so as not ‘to be floored by the strength of his feelings those memories brought’ he becomes psychologically strategic: ‘So he tried instead to control the speed of his heartbeat when Tupac’s rapping came in ….’. [36]

The psychosomatic controls in this book are engineered too by its prose and its surface qualities – apparently still but hiding turbulence, especially that of the sexual imagination. Kwame’s sexual experience is highly controlled when it happens at all, with Andrew for instance, whom Edwyn calls “fossil Fuck”, and ought to disturb him more because of ‘Andrew’s adoration of his Black skin being sinister or cliché, or Kwame’s enjoying white subservience being sinister or cliché’.[37] Learning about slavery disturbs Kwame but it is a necessary disturbance, an awakening to a historical and repressed undercurrent, and is the source I believe of the imagery of stormy seas throughout the novel for in his own head he imagines ‘the sea, rocking, slapping the outside of the ship’, the slave ship he imagines with no rescue coming from the divine Mami Wata.[38]

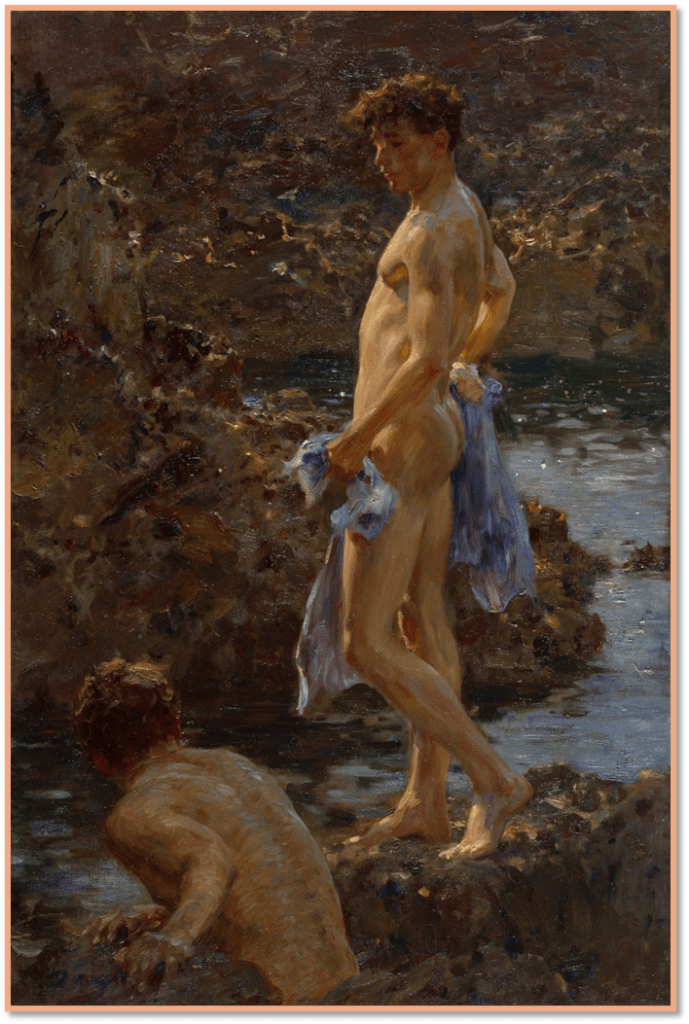

The novel works him into a new vocabulary that is Ghanaian but one in which he is Kraakye, the Twi word for ‘gentleman’ or ‘squire’ in Marcus Felix’s transformation of it.[39] Kwame loves control, even if it is only experienced within himself. But his aunties from Ghana had called him ‘a coconut’ though he thinks: ‘the problem was not whiteness or white flesh within him; he worried that inside he was entirely hollowed out’.[40] However ‘hollow’ he may be however, whiteness is the something that traps his desire into images of pallor and blankness. There is much I would like to write here, but I think I will rest with considering the role within the novel of the painting in relation to white flesh and desire: Henry Scott Tuke’s 1914 painting A Bathing Group. Here it is:

Henry Scott Tuke (1858–1929) A Bathing Group 1914, in Robinson, op. cit.: 86. Oil on canvas, Height: 90.2 cm (35.5 in); Width: 59.7 cm (23.5 in), Royal Academy of Arts Blue pencil.svg wikidata:Q270920 03/258. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Henry_Scott_Tuke_-_A_Bathing_Group_(1914).jpg

I have written about Tuke and skin colour in an earlier blog (at this link) and I still think my observation of skin colouration truer than that used in the novel for its main theme. However, the novel uses the reproduction of the Tuke painting in multiple ways and Donkor’s description of the central figure as ‘alabaster-skinned’ does not reflect the nuance I see in the skin of the model, a model Nicola Lucciani that Tuke brought to Cornwall with him from Italy. It sits in the hall of the flat Kwame shares with Edwyn. It was ‘a “housewarming treat”’ from Edwyn’s mother but Kwame, though he must ‘acknowledge’ the painting and later not damage it by bumping into it, sees it as a hymn to desired whiteness (which many Tuke paintings of Cornish boys are). What interests Kwame is a drama of the gaze between the two boys: where the standing figure ‘locked eyes with a crouching boy in the foreground, a squashed thing in the corner with his back turned towards the viewer’.[41] Expressed thus the painting could be an allegory of Kwame as a kind of Caliban looking up the transfixing eyes of the model of desire – ALABASTER white.

Indeed the allegoric quality continues to chart the development of Kwame to both Edwyn as his keeper and to whiteness as the emblem of desire. One day returning to the flat he finds himself watched by a female Asian neighbour, feeling ‘the sour persistence of that staring, and whatever judgements and misjudgements the woman might have made of him’ . What interpretations he fears from this gaze are unknown but they may be about him being queer or about his cross-racial apparent partnership (not really a partnership).

He let his focus drift towards the Tuke. It fell on the young man’s arse. Today, the gap between the boy pressed into the corner of the painting and the young man at the heart of the image – imperious nymph, rising out of the shallows – seemed even more unbridgeable than usual.

That might be the relation Kwame had made between him and the white object of desire but it is a slackening bond. At this point however, it is still the whitest of the boys (the unshadowed one) who is in control, and who is seen to be ‘about to wrap a mauve towel around himself, hiding his bum from view, keeping it all to himself’.[42] It is a novel that builds a potential that black male desire for black men is perhaps the only sure way of growing to be a person proud of one’s own black sexual identity and able to break through to explore that sexuality, free of the history of subordination to white control. Perhaps keeping their bum to themselves is precisely what you would like white people to do. And, as the novel comes near its end, it is only then that Kwame realises that his father, who struggled to exist in white society, knows that his son’s task of surviving as a queer man is much more difficult because he is Black in a white-dominated culture. Moreover he remembers his father saying that he knows that Kwame has the capacity to understand this. After sharing awareness of his past homophobia that saw queer men as ‘sissy’, ‘fairy’, ‘poof’, and like ‘a little weak breath of air’, he sees that he saw true strength in Kwame coming out as a Black queer man to him and his mother, and that he feels his son should use that strength to ‘be bold enough to ask the world for what is fairly and rightly yours’.[43]

I underestimated this novel and I think, from his newspaper critiques I have in the past underestimated Michael Donkor’s skill as a writer. He is good – very good, and I have more to find in there I think. Please read it. Perhaps discuss it with me and by all means correct my errors or failures to understand.

All the best

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Michael Donker (2024: 356f.) Grow Where They Fall Fig Tree, Penguin Books

[2] Kit Fan (2024) ‘Grow Where They Fall by Michael Donkor review – sex education’ in The Guardian (Thu 21 Mar 2024 09.00 GMT) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/21/grow-where-they-fall-by-michael-donkor-review-sex-education

[3] For Old Testament citation see: https://biblehub.com/kjv/zechariah/2.htm . The part of the novel cited is: Michael Donkor op.cit: 37

[4] Kit Fan op.cit.

[5] Michael Donkor op.cit: 327

[6] ibid: 76

[7] Ibid: 49

[8] ibid: 356f.

[9] Ibid: 127

[10] Ibid: 108f.

[11] Kit Fan op.cit.

[12] Michael Donkor op.cit: 183

[13] Ibid: 7

[14] Ibid: 1

[15] ibid: 31

[16] Ibid: 238

[17] Ibid: 183

[18] Ibid: 97 – 99.

[19] Ibid: 243f.

[20] Ibid: 90-92

[21] Fan op.cit. The Donkor quotation is op.cit: 239

[22] Michael Donkor op.cit: 124f.

[23] Ibid: 141

[24] Ibid; 158 – 161

[25] Ibid: 241

[26] Ibid: 239

[27] Ibid: 357

[28] Ibid: 275

[29] Ibid: 274

[30] Ibid: 336

[31] Ibid: 385

[32] Ibid: 106

[33] Ibid: 5

[34] Ibid: 171 for instance

[35] Ibid: 35

[36] Ibid: 144

[37] Ibid: 316

[38] Ibid: 230f.

[39] Ibid: 347

[40] Ibid: 251

[41] Ibid: 50

[42] Ibid: 202

[43] Ibid: 374f.

One thought on “This is a blog on intersectional nuance and Black queer sexuality focusing on Michael Donkor (2024) ‘Grow Where They Fall’.”