In explaining why (his name is ‘Why’ remember) he dives ‘into words’ to find ‘under the surface the right ones and emerge’ and then lays ‘them out in a quatrain and press send’, Lemn Sissay concludes: “So, taking the pressure of time as an opportunity, why not try to squeeze a lifetime into four lines? Four lines that stay in your mind. Then try again the next morning’.[1] This is a blog about visiting York on Saturday 30th March 2023 to see Lemn Sissy read at the York Literature Festival in The Grand Opera House and, of course, about the poems themselves. They are are: Lemn Sissay (2023) let the light pour in: Morning Poems Edinburgh, Canongate Books Ltd.

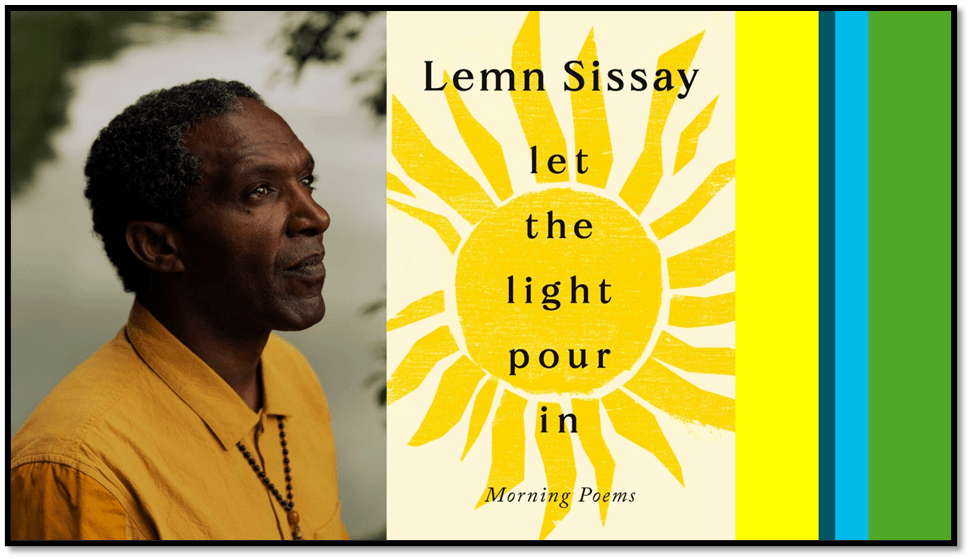

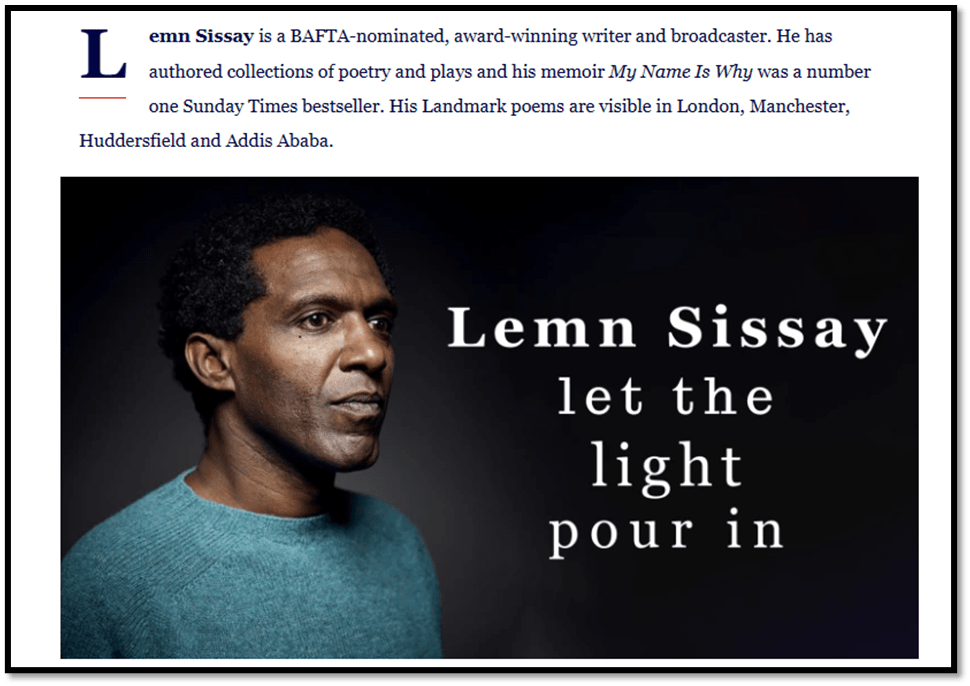

I have blogged on Lemn Sissay twice. First on the preparation I did to see his wondrous version of Kafka’s Metamorphosis with a glance at his memoir, and second on seeing Frantic Assembly’s production of that piece twice (there are links to these blogs on their description in this sentence). I had read Let The Light Pour In before the visit, but it didn’t feature much in that writing. I had a strong sense of not being ready to write on these poems, especially in the light of the statement in Sissay’s introduction: “It can take seconds to read a poem but a lifetime to understand it’.[2] There was in it a simplicity of immediate effect that is echoed by his personification of light in the first poem: ‘“I keep it simple,” said light’.[3] But I am certain that that light statement contains much dark weight that is unsaid or hinted at, and in some way, that has to do with the dialoguing of abstract binaries in language, deceptive over-ambiguous antonyms.

In preparation for the morrow, I read the poems again serially, flicking between them as I did so, for it is always a mistake to think the selection and ordering even of short quatrains does not in itself bear messages. I looked for reviews to help, but it is difficult to find sensible reviewing, even of well-known poets like Sissay. Rishi Dastidar, a poet I rather like (see my blog at this link), undersells Sissay’s achievement considerably, though he appears to like the simplicity he calls ‘unforced charm’. However, ‘charm’ is a dangerously belittling quality to find in a poet, one that drains it of any force, and yet to me, these poems had considerable force. I just could not see what it was or describe it. Dastidar says:

… there is a heavy recurrence of imagery featuring the sun, moon, night and light, so that they almost become characters: “Moon in a wheelbarrow / Stars in a skip / Dawn holds the handles / Sun gets a grip”. While some feel throwaway, the best have an unforced charm: “There’s much I’ve done / There’s much to do / But I’m undone / When it comes to you.”[4]

A very brief review is itself a throwaway but I do wonder how a poet managed to use the word ‘heavy’ when they are reviewing (as if heightened responsibility to language had been abandoned) to describe the recurrences in this poem without noticing that heaviness (as opposed to lightness) is a thing thar recurs in these poems constantly and with strong effects specific to the creation of poetic meaning, as here:

Night shifts from the dock

With a light wind in its sails

…[5]

Since the next line finds the lyricist sitting ‘sunlit’ on a rock in the sea, we can be sure that the poet wanted to evoke not only the relative weightlessness of the effect of the wind here in ‘light wind’ but the idea of lightness visible that is displacing ‘night’s’ darkness. And the sound effects of the verse too evoke the relative weight and slowness of the vowel in ‘dock’, a place of weighty stillness, and the light recurrent assonance of the ’i’s’ in ‘With a light wind’.

The only other review I found was by Fiona Sturges, of the audiobook version of the poems, but here again ‘simple’ means to this reviewer ‘charm’. Sturges even comes clean that charm is akin to ‘mawkishness’, damning otherwise the poems to a memento of the ‘every dark cloud has a silver lining’ or other clichéd kind, not usually thought the best effect of a poet’s dark grappling with meaning in language. We have to remember I suppose that Tennyson, not to mention Thomas Hardy where the error is unforgivable, was once treated as if each was ‘simple’, in message and conveyance of it, in that very way. But here is the meat in Sturges’ review. Decide for yourself.

The poems, narrated with verve and charm by their author, feature conversations between night and light – “‘How do you do it?’ said night / ‘How do you wake up and shine?’ ‘I keep it simple,’ said light / ‘One day at a time’” – and between head and heart. While there is a tendency towards mawkishness in some, others are witty or profound, telling of love, resilience and the power of nature and the elements (“The moon tells the sky / The sky tells the sea / The sea tells the tide / And the tide tells me”). In this season of short days and long, dark nights, Let the Light Pour In’s bite-size verse seeks to remind us that darkness is fleeting and that, whatever may be bringing us down, light is around the corner.[6]

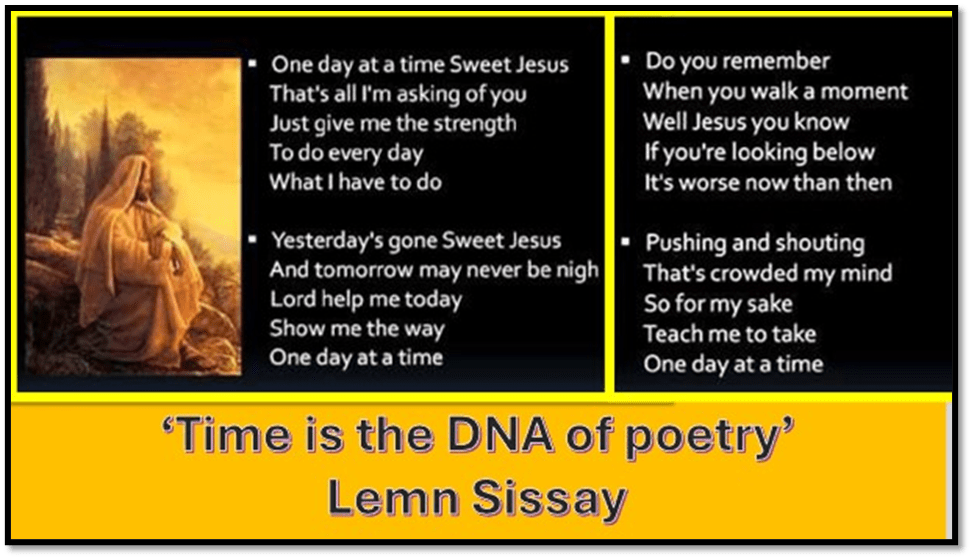

Anyone who finds charm in the statements of the light first quoted in this review has missed an education in emotional intelligence, especially about the suppressed and repressed in people who are reduced to finding hope ‘One day ate time’. When I found social work students like that, I sent them on placements in mental health facilities to see if they could learn better than they had hitherto. And of course, ‘one day at a time’ is not only cliché but one honoured by a Gospel song:

The Gospel song is a resource behind the art. It is mawkish, terribly so, in that it speaks its distaste for the world in terms of a magical wish for a personalised manner of managing time and space that has ‘crowded my mind’. In the repetitions of the line ‘One day at a time’, though, in this volume, ensures we feel the power of the felt inadequacy it expresses. In the piece quoted by Sturges, the first lyric of the book, ‘light’ is smugger than it ought to be. It is, as it were, managing its time with its mindful meditations, but not so in the lyric below:

“About time,” said night

“I’ve been waiting for you”

“One day at a time …” said light

“… Is all I can do”[7]

Where has the light of the first lyric emboldened by repetitious cliché as today’s forms of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Mindfulness demand (though their practitioners pass themselves off as full of subtlety) gone – it is beginning to collapse into dramatised silences and excuse-making against the pressures being put upon it, here by the night. Time you can see is neither simple nor merely emptily consoling. Light is not sure in this quatrain that it can replace dark nor light tones rescue us from much heavier ones, wherein ‘Morning Poems’ are also ‘Mourning Poems’, lamenting some loss or grief or trying to cover it over by an adoptive light mood.

When dark is uncomplicated by art, art reduces to black ink spilt across a page clear of messages. It is an Arctic traveller’s ‘diary of dark frost’ planned over a ‘map of black ice and fog’. For people who write of crossing a despairing space or time write a ‘liar’s travelogue’ of a place they have never experienced,. Never ‘crossed’. And here comes a very clever metaphor wherein this writing is: ‘the ink-filled heart uncrossed’. [8] I puzzled for some time why Sissay references Michael Rosen, but the truth is that this writer’s honest and nuanced account of bypassing death during COVID recovery is the ideal analogue of the truth-teller’s nuanced diary, light and dark and heavy and light and full of shadow and a determination to rise again.[9]

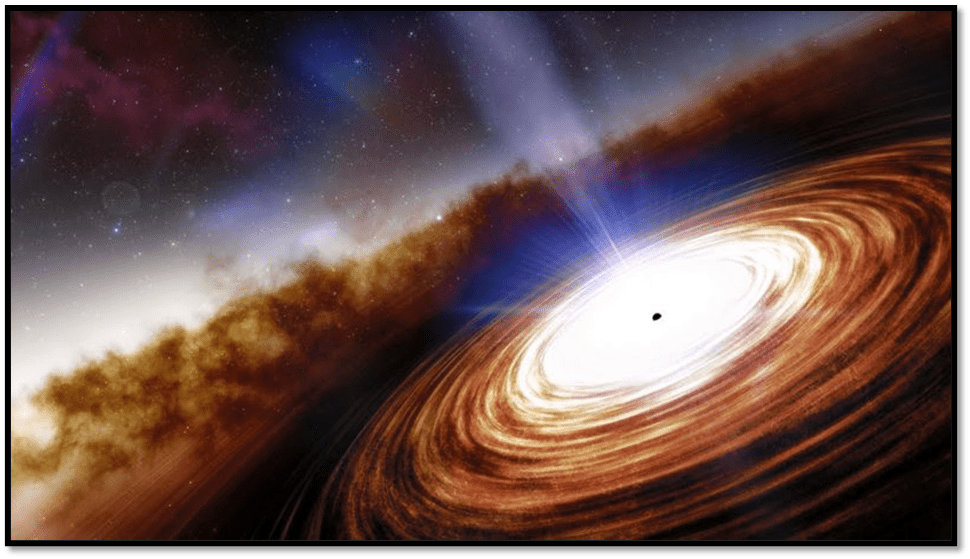

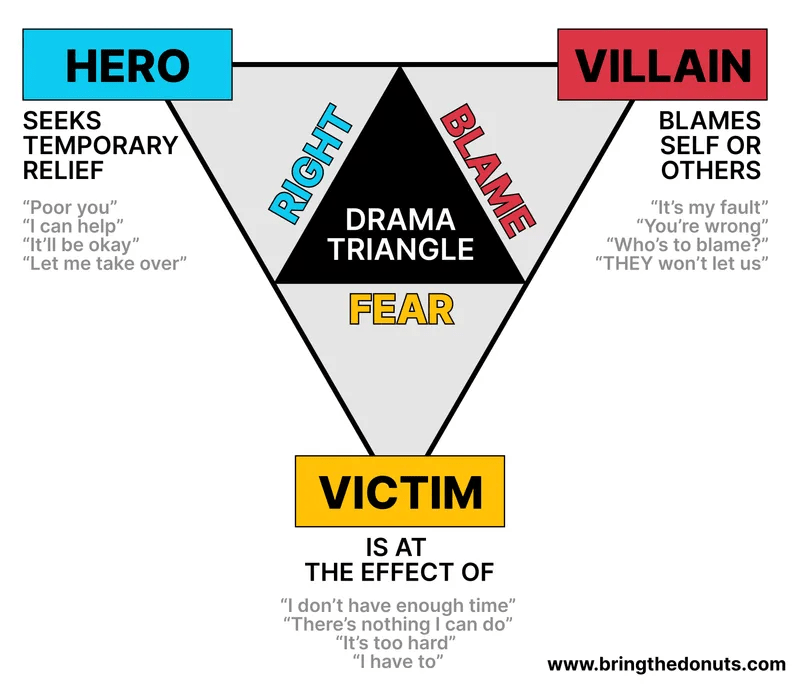

It is clear that these poems are about what gets you up in the morning, or rise with the sun, when getting up or rising is the last thing you want to do and the context of loss is alone justified by that. Many kinds of loss are, as I shall show later, involved in these poems – the breakdown of a relationship (and even its analysis using Karpman’s Drama Triangle, the loss of family bonds such as those related to children-in-care but not only those children (themes in so much other work by this artist), the loss of a felt integrity in self or other or in an oppressed people before it knows how to rebel against injustice. But if those losses are ubiquitous so are their opposites like the meeting of destined friends or lovers, reparation in breaking relationships, ‘peace talks’, wholeness found or restored and light returning diurnally and seasonally in qualitative and quantitative terms (as a mass or volume of light, perhaps even a quasar) when light seemed gone forever (my emphasis in the quotation).

Rainbows do it in the car wash

Eyelids do it on the eyes

Quasars do it in the cosmos

Make like the sun and rise.[10]

Artist’s concept of quasar J0313-1806, currently the most distant quasar known. Quasars are highly luminous objects in the early universe, thought to be powered by supermassive black holes. This illustration shows a wide accretion disk around a black hole, and depicts an extremely high-velocity wind, flowing at some 20% of light-speed, found in the vicinity of JO313-1806. (https://earthsky.org/astronomy-essentials/definition-what-is-a-quasar/)

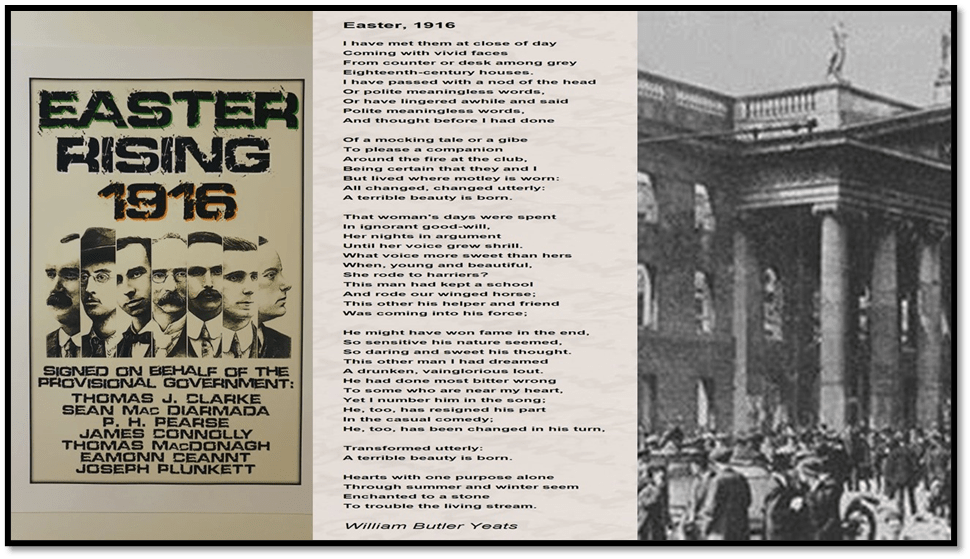

The metaphor that tells of the nuance involved in the task of rising or getting up in the morning is that of rising, set against its binary opposite of falling, or even more negatively the ‘unrising’ of the seriously depressed. If we ‘Make like the sun and rise’, which I think is also the ‘son’ that rises, we defy not only the gravity which causes the sensation of weight rather than lightness, but the dark encompassing those who sleep or wake in the night and the right we have to rebel against the weight of oppression. Thus remembering a ‘sunrise’ after a loved one leaves or rejects you might look not like a ‘rise’ but ‘The falling cloak of mist? The roiling regret’. Yet the very next lyric reinstates the other as a seasonal, religious, and political elevation of soul and spirit. It is a tremendous poem:

Be my Easter Rising

Be my imperfection

Be my peace talks

My rebel insurrection.

No quatrain better expresses the nuance of rising where hope and a remaining sense of the unfinished, and therefore imperfect, is found. It recalls W.B. Yeats’ Easter 1916 of course, a recognised master of nuance, but does so in order to code complexity into this poem, that reminds me of nothing more than the disguised complexity of Tennyson’s In Memoriam. It is why the poem does not have the simplistic message read there by Fiona Sturges.

For light and dark do not merely replace each other, even in defiant revolution in the name of justice, they find variation in each other and relativity to each other, as does the heavy and light likewise. Light and night converse because they rhyme, are homonyms as well as synonyms, they make each other.

“I am not defined by darkness”

Confided the night

“At dawn I am reminded

I am defined by light”[11]

And even the darkest of darkness and depression when asking its meaning deepness and earnestly wishing to know and become other finds itself asked not to listen but participate with light: ‘Be light upon the shadow / Rise up and lean in’.[12] Shadow lies in the cusp of light and dark and hence frequently makes an appearance, but not to rejected by the light that falls’ in as it ‘rises’ but to be kissed:

Raise me with sunrise

Bathe me with light

Kiss all the shadows

That fell from the night.

That the poem uses its one reference to Seasonal Affective Disorder (happily with the acronym SAD) As we rise we kiss what feels fallen, and make it light in our arms and eyes. Yet SAD is a myth too, but why not celebrate the myth Sissay thinks and dream that all depression is only seasonal and ‘rise on light and chant / It’s spring, it’s spring, it’s spring’.[13] We will return to kissing too however again in the is blog.

However, we can not leave the complex extended metaphor of rising yet. Rising is a sign of hope, of the emotions turned positive and equated with getting up in the morning as if we have – nowhere more clearly than in the lyric, ‘Rise, rise from out your bed’, a lyric that turns futureward with a vengeance.[14] But sometimes the lyric voice is just cheering itself up in ‘sunrise’ as when it ‘dances on bridges’ and bathes in the ‘laughter of light’, for a ‘shadow’ still ‘falls behind me’ and catches up quickly however ‘all right’ you say it is.[15]

Sometimes the ‘lifting’ you feel is of the most superficial kind, as if you were a ‘lifted kettle’, whose ‘rise and shine’ is patently false: just like the advice the lyric that says (it is still used in mental health rather pathetically): ‘One cup of tea / And the world is mine’. [16] And, as I have hinted, if we fail to see rise as an antonym of fall and/or rest, the poem invents a new one, but not a new one for the depressive, the ‘unrise’, the failure to rise.

To unrise is to sleep

To unhand unrest

Unless it’s sunrise

Uncoupled from an s[17]

This light and witty poem, happily playing, somewhat child-like, with words, actually evokes a whole syndrome of sleepless misery in the mornings / mournings of the miserable. The power of a prefix like -un is unleashed in its full ability to negate all peace in a much later lyric:

To unwind he unpicked the thread

Got up and unmade the bed

He undrew the curtains and, uncertain,

Left what was untold unsaid[18]

It ought to have a rising rhythm getting out of bed – this does not. No person ‘unwinds’ emotionally thus.

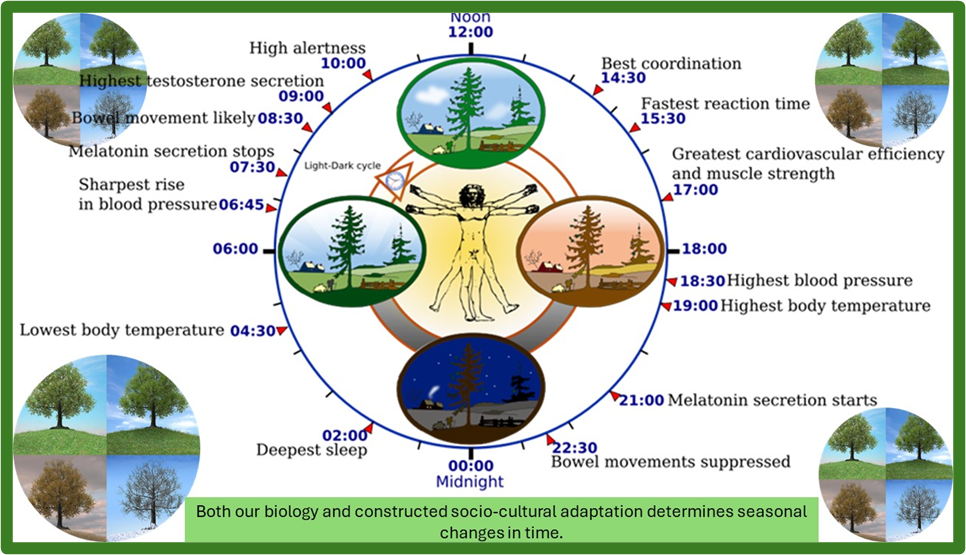

For time sometimes refuses to look as if it moves on. Who is to blame? If Time were only experienced cyclically, as poetry has oft tried to persuade us since the Greek dithyrambic choruses and yet failed with T.S. Eliot, things would be much easier. If it was merely about biological internal calendars and clocks the same would be true (though as with all other poetry, this set of lyrics invokes such cycles particularly the circadian (daily) one, which experiments support as being internalised in many animals, including human ones.

In let the light pour in: Morning Poems time is experienced in terms of the interpretive frameworks of those who experience it, including those ubiquitous personifications of night and day, light and dark, raising and falling rhythms. ‘One Day at a time’ is a rather linear approach to time, owning to serial sequence only, but mood is clearly seen as determinant on that experience. When the moon complains of their tiredness and complains of being ‘heavy with night’, the sun tells them to keep it simple and light. It is the most beautiful of plays with light understood as either an indication of weight or the presence of light and of the social tones for which each become a metaphor.[19] Time is a matter of ‘translation’ of such words at time into the ‘language of the heart’ in which mood determines not the sense of beginning and ending, sense of what dies away and what is renewed, at its simplest in: ‘The darker the ending / The lighter the start’.[20]

Indeed whether time is simply sequential, cyclical or experienced in any other way seems to depend on the ability to be more knowing of one’s subjective drives in life and ability to, as it were, allow time to pass. In one lyric resolution comes with the reassurance that: ‘This too will pass’.[21] Time can feel though to be a thing that waits upon the belated but expected and in its impatience it can rush the outcome and be overhasty as night is in speaking to light as already quoted, or it delays outcomes by holding on and refusing to let go or letting go but to no effect as for the plop of a stone dropped in a lyric that ends: Wait, wait, wait’.[22] Time can feel frozen: ‘a shadow boxer frozen in time’.[23]

But the play with subjective time is most affecting in feeling like a thing ‘left’ by what holds it together, wherein without moving from very ordinary language the light of morning becomes dark, stilled in time: She left me / And when I wake / my heart this morning / breaks”.[24] Or less plangently and lighter when ‘night meets a new day’, a re-bound relationship perhaps:

“It’s like speed dating,” said the sea

“In slow motion”

What kind of time experience this conveys is in part one with the laughter it evokes. Sometimes the poem takes a cliché, like ‘time and tide waits for no man’ and opens it out tragically:

Crack the dawn awake

Break the tide of grief

Time and tide won’t wait

Water rushes beneath[25]

The sudden rush of fluid here is intent on showing that grief can’t be broken by will though timely dawns still break. For you can’t hold on to time without denying its very nature, as in this confluence of meaning between how time passes and loves fade:

Remember you were loved

As day loves night, and so

I held you one last time

And then for love let go[26]

If that poem is about holding time, the next in sequence chooses a cognate word for an attempted manipulation of its process (that of keeping ‘Keep it in the day’). But to ‘Hold on and hold still’ works not a jot, for, however you try and contain the markers of time (in a wheelbarrow or skip), if ‘Dawn holds the handles’ (and that’s some motorbike image) ‘Sun gets a grip’, and then nothing holds on as it races forward.[27] Keeping and holding imagery come together regarding time here:

“How do you hold on,” said night

“To peace in the day?”

“To keep what I have,” said light

“I have to give it away”[28]

I think the analogy that is so often made between time as a thing that rums smoothly, or is fragmented and broken, or alternatively paralysed, and human relationships in making OR IN PERIL has already been established. They are brought together in the light and night personifications which are so much more than Sturges’s ‘conversations between night and light’, for they are not only conversations but engagements often with a romantic, familial or combative tone (sometimes all three – relations are built, sustained and broken). Worse, of course, when your partner takes the ‘bloody kettle’ with her. [29] One meeting takes form in Romantic French in a lyric that might almost feel like Verlaine:

Ecoutez le murmure

De la lune et soleil

À l’aube, ils chantant

“Accueil, accueil”[30]

The Grand Opera House Interior, York

But what comes together in meeting can also fall apart, and sometimes the falling apart is more nuanced fun than the formal coming together:

Let’s fall apart together

Said darkness to light

Tumbling into sunrise

And out of sight[31]

Some partings are over-analysed as if in the evocation of Karpman’s Drama triangle, as each calls out the other’s lying insincerity.[32]

Instead of the drama, we can introduce the shadow of nuance into a relationship. The partners introduce the shadow of a third person or imagination of one desired. This is one of the ways in which the poem develops the image of kissing shadows in the cusp of dark and light, night and day, moon and sun. Of the nuance, see the example of dawn and night at play in kindly parting on the space where the ‘waves break on the beach’s back’.[33] The nuance is the more beautiful :

In that space between want and wish

The gap betwixt a dream and myth

Above the sea below mist

The you, the me, the kiss.[34]

Some kisses are those of Winter and what should be tender turns ‘cold’.[35] The tougher break-ups are where ‘Light breaches darkness / every single day’ and the whole thing breaks down into a shouting and screaming match.[36] We would be wrong to see only one kind of relationship building and breaking here. The presence in the set of poems about Ethiopia (where Sissay’s birth mother is located in his memoir My Name is Why) and of the plaint of cared-for children broken by the care system. Rejected and blamed for the break-up by his foster parents, and perhaps rejected by this birth mother, some of the poems are about lost or broken ‘twisted’ roots.[37]

But Lemn Sissay knows, and he wrote into his own version of Kafka’s Metamorphosis what was in part already there, the cruelty in potential of familial love bonds. In a sense, I think Sissay wants us to understand the relationship in life between performance and what we understand as authentic. I feel that because of the many theatrical metaphors in the collection.

Of course, they aren’t just theatrical. The poem on the Apostrophe is about both a feature of classical drama and punctuation, for punctuation is very controlled in this lyric, used to create meaning not to follow form alone. It is handled so lightly in some cases, you could easily not see that metaphoric communication is there, as in this case.[38] At other times the theatricality is as plain as it could be as in the relationship between dark and light plays with the pauses used in theatrical convention between the end of a play ‘and the applause’, with ‘A graceful bow from darkness / And a standing ovation of light’. The ethics of the characters at play here are delicately and complexly handled. Do they fake it, show envy to each other, or merge in each other’s glory. But the performance of both love, and perhaps even performing the handling of time in our mutual lives, is there in what follows:

The day’s the play

The sun’s the star

The sky’s the script

I learn it by heart[39]

My favourite metaphor is when ‘Up’ (a veritable personification of the performative) in a place where the ‘centre’ of the binaries up stages both Night and Dawn at stage left and right. And that is where Sissay will ‘Write, write, write’.[40]

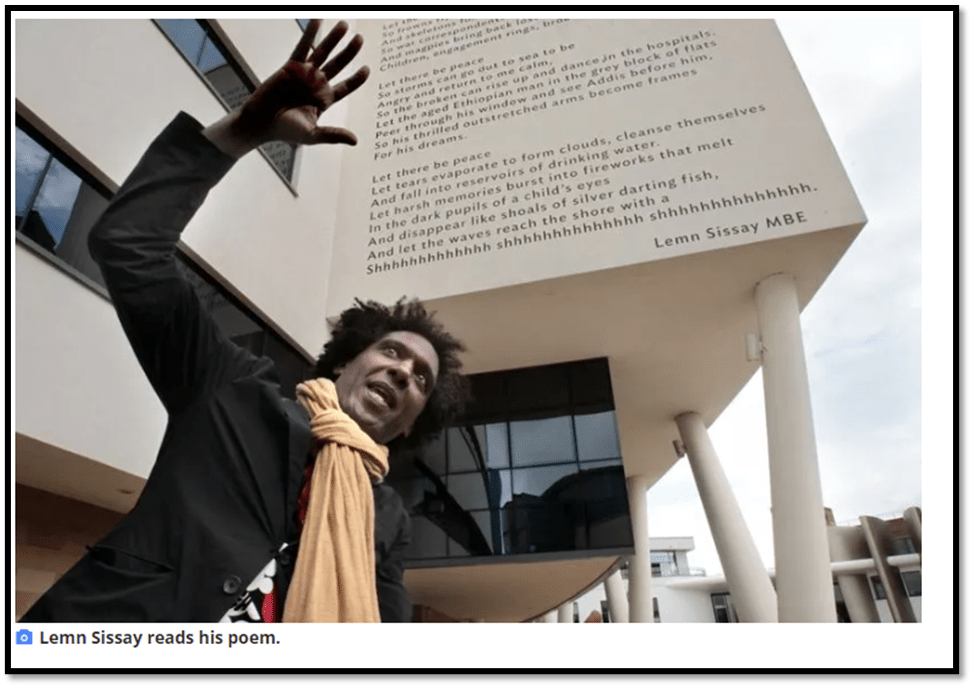

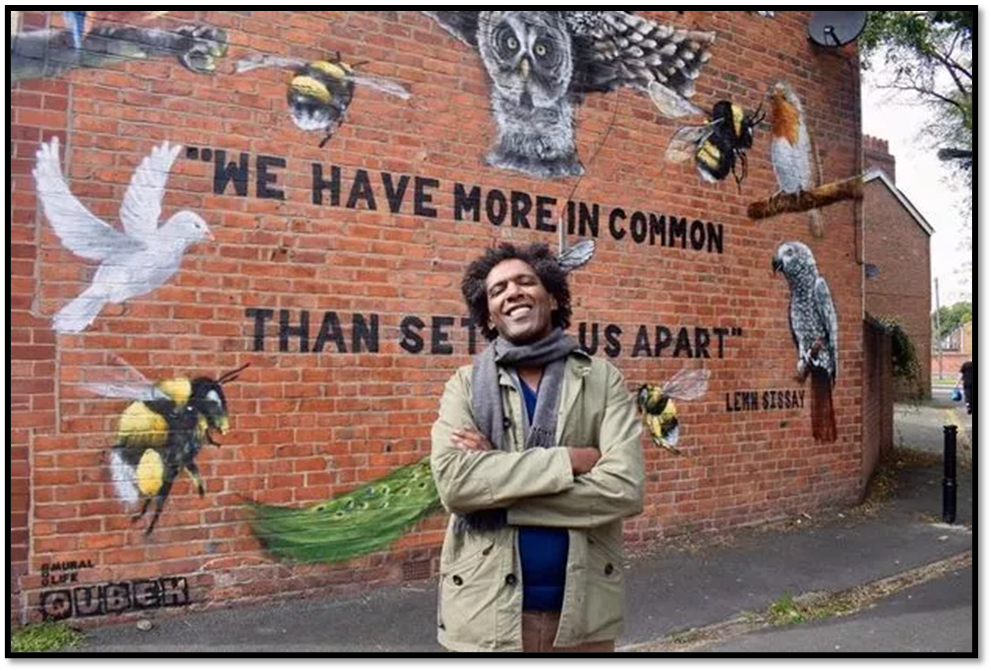

I could of course write more and more about this beautiful collection but my aim here was in fact to prepare myself to hear Sissay read in York tomorrow at 12 midday. I wanted to end with performance values in the poem for I suspect that is why I needed to see this poet in the flesh, to see if and how he, in these poems is a PERFORMANCE poet. It may not be the case for many are now written up in public places as a poetry of the people – even In Huddersfield, the town near to my childhood’s breaking. But I look at this picture (from a Huddersfield newspaper, of him reading a poem inscribed on the University there (that wasn’t there when I was a child) and I can’t, seeing this take of him reading in a photograph from Yorkshire Live , I can’t imagine he isn’t a performance poet.

Even in Manchester, with lines from this volume, what I see on the wall I really love. I can’t wait to see him and hopefully add to this blog a few impressions of him as reader and person before it is uploaded tomorrow late afternoon.

The day became stressful. I got to Durham, but there were trains cancelled, lots of them including mine. I hope Lemn will help the situation. Let’s hope trains are renationalised.

I had to run to the theatre from the station but, boy, was it worth it. If I had worried about the lack of performance, I could not be more wrong. When comic, he was tremendous. When passionate about the care system, he was electrifying, but above all, he showed how moving his poetry is, how complex it’s effects, even in the variations caused by the audience. A poem he read, Invisible Kisses, he read both as he did for use in weddings or funerals. It was appropriate each time, the context of love and its hidden character always precise when meaning shifted to meet the people hearing it.

He started though with Mourning Breaks, a poem that confirmed to me that morning poems are mourning poems, that breakage comes in joy or in letting go, for it is about a man on the edge, hanging on but eventually letting go to find he had wings. Mourning is not a negative process sometimes.

And then Lemn read from the volume I talk about above. He even answered my question about the exploration of ‘unrise’. His explanation was beautiful.

As he spoke to his audience, he built connections that insisted on nuance; that comfort and discomfort require more than conversation together like light and night, to realise the miracle of both up-rising and sunrising. He told us he wrote those poems because he is a ‘morning person’. With a shared, I hope, smile, I thought maybe that it was because he was also a mourning person; for life can only be lived when mourning transforms into peace and forgiveness. However, forgiveness can happen only when we remembers that this is what mourning can be if we let it spin with nuance in our life.

And he signed my books. He is wonderful.

Of course, the train home was cancelled. But I am on one now: feeling love all around.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

PS Do read Lemn Sissay’s wonderful poems. Please. Buy them even.

[1] Lemn Sissay (2023: 1f.) let the light pour in: Morning Poems Edinburgh, Canongate Books Ltd.

[2] Ibid: 1

[3] Ibid: 5

[4] Rishi Dastidar (2023) ‘The best recent poetry – review round-up’ in The Guardian (Wed 30 Aug 2023 11.00 BST). Available: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/aug/30/the-best-recent-poetry-review-roundup

[5] Lemn Sissay op.cit: 120

[6] Fiona Sturges ‘Let the Light Pour In by Lemn Sissay audiobook review – salutations to the dawn’ in The Guardian (Fri 12 Jan 2024 12.00 GMT) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/jan/12/let-the-light-pour-in-by-lemn-sissay-audiobook-review-salutations-to-the-dawn

[7] Lemn Sissay op.cit: 158

[8] Ibid: 11

[9] Ibid: 164 (references I believe Michael Rosen’s (2021) Many Different Kinds of Love: A Story of Life, Death and the NHS London, Ebury Press.

[10] Lemn Sissay op.cit: 15

[11] Ibid: 13

[12] Ibid: 19

[13] Ibid: 57

[14] Ibid: 127

[15] Ibid: 134

[16] Ibid: 23

[17] Ibid: 103

[18] Ibid: 172

[19] Ibid: 6

[20] Ibid: 130

[21] Ibid: 173

[22] Ibid: 85

[23] Ibid: 84

[24] Ibid: 63

[25] Ibid: 80

[26] Ibid: 46

[27] See ibid 54 & 55.

[28] Ibid: 97

[29] Ibid: 133

[30] Ibid: 17 (My translation : Listen to the whispering / of the moon and sun / at dawn, they sing / “Welcome, welcome”)

[31] Ibid: 170

[32] Ibid: 146

[33] Ibid: 112

[34] Ibid; 121

[35] Ibid: 149

[36] Ibid: 142 & 143

[37] See, for instance, ibid: 92 & 108

[38] Ibid: 107

[39] Ibid: 129

[40] Ibid: 27

One thought on “This is a blog about preparing for and visiting York on Saturday 30th March 2023 to see Lemn Sissay read at The Grand Opera House: Lemn Sissay (2023) ‘let the light pour in: Morning Poems’.”