Helena Kennedy in her review of Atef Abu Saif (2023) ‘Don’t Look Left: A diary of Genocide’ (Comma Press) says rightly: ‘The people of Southern Israel undoubtedly suffered terrible atrocities on 7 October 2023 at the hands of Hamas. However, we have be capable of holding two truths in our hearts’.[1] Though I agree, I think we nevertheless have to hear the voice of the currently oppressed without demanding of them a recycling of their story from another perspective that is antagonistic to their interpretive framework, particularly when that voice is being actively repressed as part of the cost of war.

Children in a damaged building in Rafah, Gaza Photograph: Xinhua/REX/Shutterstock available: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/14/dont-look-left-by-atef-abu-saif-review-in-the-line-of-fire

In yesterdays blog (at this link) I was about two-thirds through my reading of Atef Abu Saif (2023) ‘Don’t Look Left: A diary of Genocide’ (Comma Press) but in fear and awe of what it revealed to me. There I wrote:

I am reading a wonderful but fearsome book currently by Atef Abu Saif called Don’t Look Left. I will blog in more detail later. It is a diary of Abu Saif’s life in Gaza during the first 85 days of the Israeli onslaught on it. Abu Saif is part of the Palestine Authority in the West Bank and ideologically opposed to Hamas, and more so to the militant wing that terrorised Israel and became the pretext of a war vastly out of proportion to the crime, even had it been a crime committed by Gazans as a whole, which it is not. But he reminds us that we in the West often decide on matters without knowledge of how other people’s lives are lived – of the event called the Nakba, which Westerners rarely hear, or speak, of but that included the islanding off of Palestinians in stateless condition, in either (and the historical conditions cycled around since 1948) occupied and stateless portions of land and then in land surrounded by walls, munitions, armies and gunships off the coast, as in a prison. It might seem offensive in the light of this book to say to Atef: “No man is an island …any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

Why? Because we are complicit in islanding the West Bank and Gaza, in arming the only state in the area, and one opposed to Palestinian statehood currently, to ‘defend’ itself by ‘offensive’ arms we supply, and support its laws offering unequal access to land, housing, work and freedom of movement to Arabs. The bell that tolls for the current number of Palestinian dead would toll until silenced by wear. Atef talks about being a ‘displaced person’ by the war strategy in Gaza, the creation of a space where nowhere is safe or will remain so and the destruction of harra, a word in Standard Arabic that means neighbourhood, but in Atef’s writing grows to mean that which makes a self a self.

A harra doesn’t just consist of its buildings and streets, it’s made up of all the memories of all the people who have lived there, the people and the relations and the relations that have developed between them over time., it is not just where you were born, it’s a place whose story merges with your own.

Atef Abu Saif (2023: 93) ‘Don’t Look Left: A Diary of Genocide’ Comma Press.

Now I have finished the book, I have decided to blog on it. Nevertheless, it raises issues for me that I cannot feel as simply about as I did above. I read a review in that interim too by Helena Kennedy, that I had previously cut from The Guardian to read once I read the book itself. Kennedy is clearly as moved by the book as I am, finding it ‘hard to describe the cumulative effect this devastating chronicle has over 280 pages’. Her summary, however, is more circumspect. Whilst Abu Said makes no bones of calling the Israeli offensive a genocide, and one that has accumulated since the Nakba of 1948, Kennedy, ever the lawyer, says that this is for the international court of justice (ICJ) to decide ‘in the fullness of time’. She concludes with it a statement that ‘this war has to stop, and a truly just peace secured’. Previously to this, she also stayes the view I cite in my title that asks us to remember that the suffering of others than those in Palestine are somehow part of this same story, but not as it is told by this book: ‘The people of Southern Israel undoubtedly suffered terrible atrocities on 7 October 2023 at the hands of Hamas. However, we have to be capable of holding two truths in our hearts’.[2]

Kennedy’s caution as a writer and opinion-former here is necessary. Whilst I am neither of those two things, the same caution ought to be exercised perhaps by me, for, in justice to myself, I have always felt appalled by Anti-Semitism, although I have no doubts that such charges are currently being used in effect to exonerate a modern warlike state from criticism of its policy and implementation thereof. When state policy, especially, extends to the consideration of genocide as unstated aim of its policy, even more circumspection is needed.

I have no doubt that what is taking place in the Middle East is genocide and it is important not to confuse that with the fact that Jews have been a main target of genocidal government action in Europe and elsewhere in history. How then should we read this book without forever invoking comparative references back to either the European Holocaust or the events of the 7 October 2023? Both later events are horrific, both pernicious politically and both examples of human behaviour gone badly and wickedly wrong. For, if we constantly make this reference back, we inevitably cast doubt on the story we are told in this book, which inevitably involves some bitterness at the selectivity of the story heard and retained in appropriate sequence by European readers like myself and Baroness Kennedy, though her knowledge clearly and massively exceeds mine.

The dismay of Gazans at Western response to the war and calls for ceasefire is recorded many times in this diary, both in reporting the war, contextualising it in Palestinian history and interpreting it without such firm knowledge, even of events considered as major as the Nakba, wherein ‘800,000 Arabs were driven out, their men shot, their women raped, their villages set on fire, their townspeople slaughtered’.

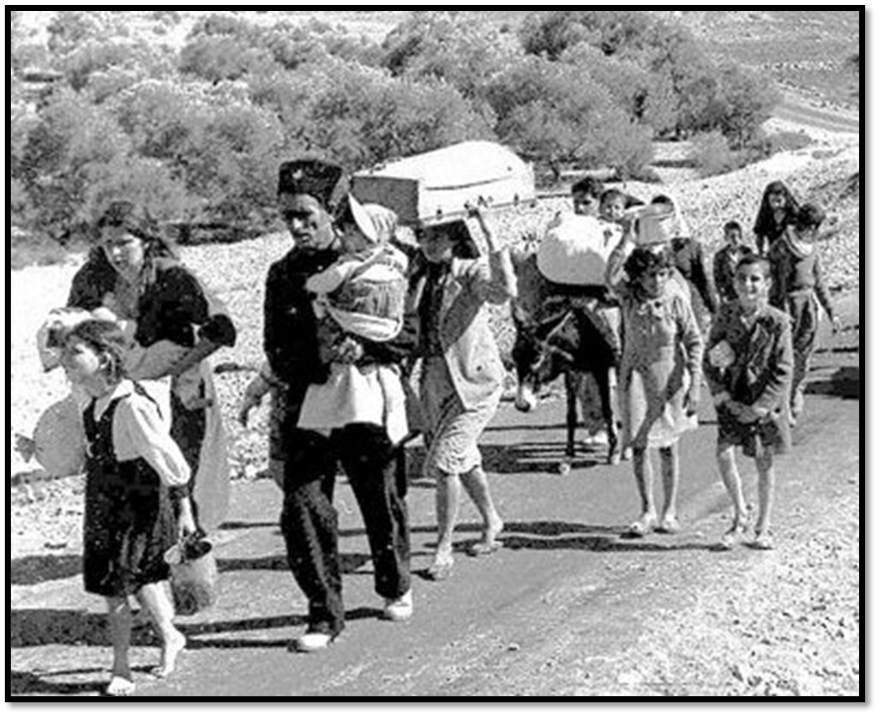

From Arab perspectives, the creation of Israel is an ongoing and now expanding fact, through successive war, cold war, and war exercises around Gaza based in ‘Terror’. From this perspective, one might understand why the events of the 7 October have to be put into a rather different framework so that Abu Saif does not feel he should address them here. According to him, of the Nakba: ‘the rest of the world still doesn’t know what the word ‘means. Just as now, when we say the ‘New Nakba’, the world refuses to learn’.[3] Later, he remembers his grandmother Elisha’s stories, of having a large villa housing an extended family in Jaffa, being thrown out of it in 1948 and her family scatterd in diaspora throughout the entirety of the Middle East, ‘before she came to live in the narrow little house that became my family home in the Jabalia refugee camp, having walked over hot sand with thousands of others, her young children in tow’.[4]

What concerned me as I read through the marked days of this journal is how each successive day and date of this story brought back to me the etiolated version of the story of the Gazan population we received on the BBC. Of course, it had to be. BBC journalists were stationed in Israel whilst we received, what Abu Said sometimes felt he was living in: ‘ a bad documentary, a propaganda piece that only serves the country it’s being shown in, reaffirming all their viewers’ prejudices, all the lies the media have fed them’.[5] As he hears the justifications for the Israeli campaign he recites the statistics of the war dead, starving and displaced and the stories of his wider family and friends killed shortly after we meet them or brutally mutilated like his cousins, one who ha lost both legs and a hand, the other, her sister, taken into a mental hospital. What the West gets he knows is not these ‘real narratives’ but ‘a grotesque charade of political gesturing, a world in which morality is just an empty performance, disconnected from real events’.[6]

Compare then how we in Britain heard of the first of many attacks (they stopped being reported so carefully handled were they by the IDF) of the Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City. The constant return there of the IDF, which the West does not hear about, could not be explained by supposed military placements under it but by the fact that a great many citizens were making it their home, and it became their graveyard too: Atef gazes over ‘this new town of Al-Shifa, a town made out of refugees from the city that used to be known as Gaza’.[7]

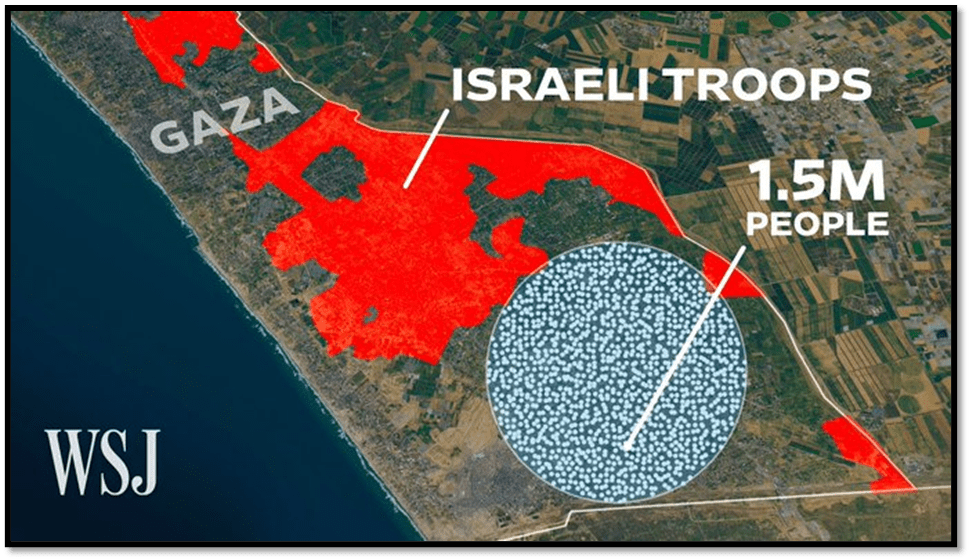

Displaced from there, people erratically go to the prescribed declared ‘safe’ towns by the IDF, Khan Younis, and Rafah in the South. As the days expand, so do the safe spaces diminish. Khan Younis and its hospital are battlegrounds, and Rafah is declared the only safe space. People flock again to the road from Khan Younis to Rafah, knowing full well they are still potential targets as they move: ‘Khan Younis is ‘unsafe’ now, and everyone must go to Rafah’, dropped leaflets in red warn the population.[8] Now in Rafah camp, mangled by winter weather, the story becomes one of normalised despair: ‘Death has been normalised. Waiting is normalised. Worry is normalised. … Many people talk openly about not wanting to carry on’.[9]

One in three children under age two in northern Gaza are acutely malnourished. Photo Courtesy: UNRWA

That the book was written means we know the writer survived. On day 85, he is assigned to a list for movement across the Rafah Crossing to Egypt with his son, leaving his own father, not only without mobility but also motivation, well behind him for his father would not, could not, carry on but wanted the younger family so to do. Atef is no ordinary Palestinian. He has written on past wars and is a member of the Palestinian Authority, supposedly in charge from the West Bank but not of Gaza, even though his family spans the areas. He is a cultured man. His death might be noticed. The scene in Gaza is described as like Eliot’s The Waste Land, the terrible hopeless ennui as like Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. As Culture Minister for the Authority, he has been responsible for putting the dance form, Dabkeh onto the list of protected parts of Palestinian ‘intangible culture’. The UNESCO Heritage Fund passes it through on Tuesday 5th December 2023, whilst Khan Younis awaits the IDF.

The fate of art still seems to matter, for a while, to Atef before his attention is called to the proximity to him of other, and incalculable, losses. However, the book plots also, along the way, other aspects of the cultural genocide of Palestine and what it means to its people such as the deliberate burning of the Gaza Centre for Culture and the Arts. Atef’s plays had been staged there and many cultural centres and the hundreds of paintings they store are now ‘burned or damaged beyond repair’.[10] He also hears of the targeting of Palestinian writers, even poets, the cutting off of writers from the ’well’ of images that is a writers Harra or home, the enforcement by starvation and loss of fuel of cultured families to now burn their books to keep the family alive in the flesh, or if not purposively being ‘buried under rubble’.[11]

The book continually returns to questions of whether, when vast numbers of innocent children are dying, art matters at all. We meet many artists and writers (novelists and journalists) asking this question, but he and novelist Kamal (both having written well-received plays and books) no longer ‘have the energy for this kind of conversation. In the end, a writer is just a man or woman who wants to take care of their kids’.[12]

But as I was reading this book and nearing its end, the news broke that the declaration of Rafah is now, this very day (though it has been bombed continually), itself a ‘battlefield’ – one that will be operational within the next few days. In some estimates, 1.5 million refugees live there in temporary encampments. At the end of 2023, Atef says that he knew that that when the guns are put down, by Ramadan he thinks it will happen (as we all did), the future will still be bleak for surviving Palestinians. Then they will realise the enormity of their losses and understand the ‘new conditions’ of a possible re-Occupied Gaza clearly as if is resettled by Israeli homes.[13]

But Ramadan has come. Gazans are still held in a space between armed-with-steel pincers that can only lead to an even greater death toll. The UN has now said Rafah is a last straw, but I expect after mass deaths that they will suck up the excuses.

Especially moving in this fine book are moments when Atef thinks about the history of his family, where what is small like a home to which one has been displaced from a large villa in Jaffa can seem something huge in its significance. But even these are now destroyed: “Now there is no ‘there’”.[14] And when the past and present are destroyed all he expects is that ‘a whole world of suffering will open up to us’.[15] Moreover, I guess that Atef must now feel the future in Rafah that will start unfolding in the next few days is well beyond his blank expectations expressed in the book. That probable terror will confirm again his fear that the enemies of Palestine are more brutal and uncaring than anyone could have thought possible. Visiting cousin Widdad in a psychiatric hospital, the sister of Wissam’ (herself living without three limbs), she says to him that it is:

… better if she dies. “What do I have to live for? She asks. “What is there even for Wissam to live for? How are we going to live? The only good people in the world have died [she means her parents]. Why should we live on after them? I can’t do it,” she concludes.[16]

This is the most potent of the suicide wishes in the diary and intensely moving, for the greatest despair is that when we look to the hopelessness of the future of those we love rather than our own. However, Atef is perhaps the more chilling in his thought process when he reports the thoughts of people he meets in the street who say things that really penetrate analytically and emotionally. He meets an old school friend on the 13th of November who says to him:

“It’s like we’re all being played in one big PlayStation game,” Alaa; says. “We’re the characters and they” – he means the Israeli army – “are the players. We move when they us move. We die when they let us die. They control us. We’re not human beings, we’re characters in a game.”[17]

It is a ‘game’ in which even ‘peace’ means being contained in a virtual prison with walls and hostile eyes all around, even in the seas where the warships were playing war games even before this war, is no way to experience and thrive in time. It is a game we are allowing to close in a deadly endgame, and not just to the spirit.

Do read his book. It stuns. And, of course Kennedy is correct to say we must ‘be capable of holding two truths in our hearts’. Just beware of that heart splitting!

With love Steven

[1] Helena Kennedy (2023: 52) ‘Don’t Look Left by Atef Abu Saif review – in the line of fire’ in The Guardian Culture Review (Sat. 16/03/2024, 52) Also available: Thu 14 Mar 2024 07.30 GMT at https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/14/dont-look-left-by-atef-abu-saif-review-in-the-line-of-fire

[2] Ibid.

[3] Atef Abu Saif (2023: 190) ‘Don’t Look Left: A Diary of Genocide’ Comma Press.

[4] Ibid: 202

[5] Ibid: 38

[6] Ibid: 178

[7] Ibid: 111f. (Monday 6th November 2023)

[8] Ibid: 207 (Tuesday 5th December 2023).

[9] Ibid: 220 (Sunday 10th December 2023)

[10] Ibid: 191 (Thursday 30th November 2023)

[11] Ibid: 125 (Friday 10th November 2023)

[12] Ibid: 263 (Tuesday 26th December 2023)

[13] Ibid: 234

[14] Ibid: 203f.

[15] Ibid: 234

[16] Ibid: 277 (Saturday 30th December 2023) Day 85.

[17] Ibid: 133 (Monday 13th November 2023)

One thought on “Helena Kennedy in her review of Atef Abu Saif (2023) ‘Don’t Look Left: A diary of Genocide’ says rightly ‘we have to be capable of holding two truths in our hearts’. This blog reflects on that & the book.”