Why did John Schlesinger and James Lee Herlihy respectively say that Midnight Cowboy was not a “gay movie” nor a “gay novel”?[1] This is a blog on the myth of the MIDIGHT COWBOY as discussed by Glen Frankel (2021) Shooting Midnight Cowboy: Art, Sex, Loneliness, liberation and the Making of a Dark Classic, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

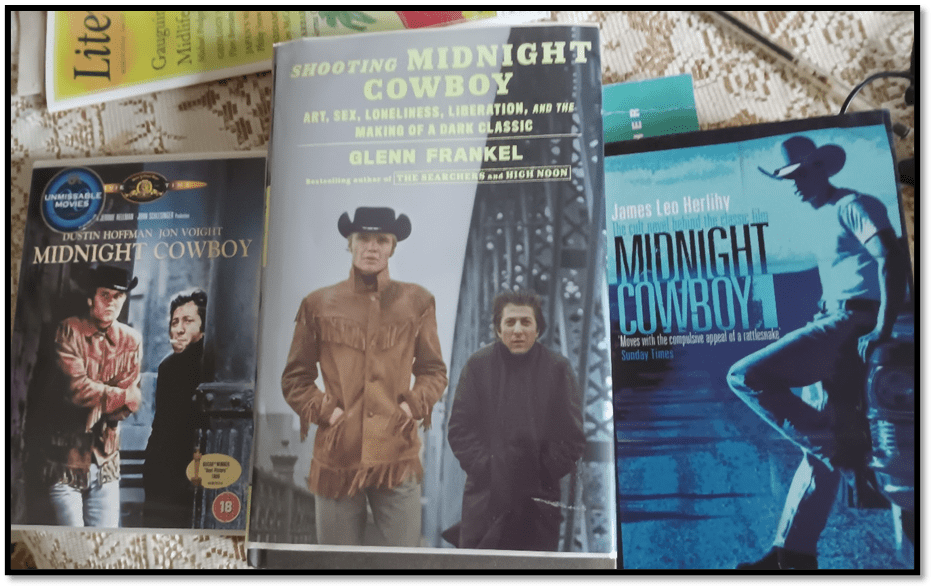

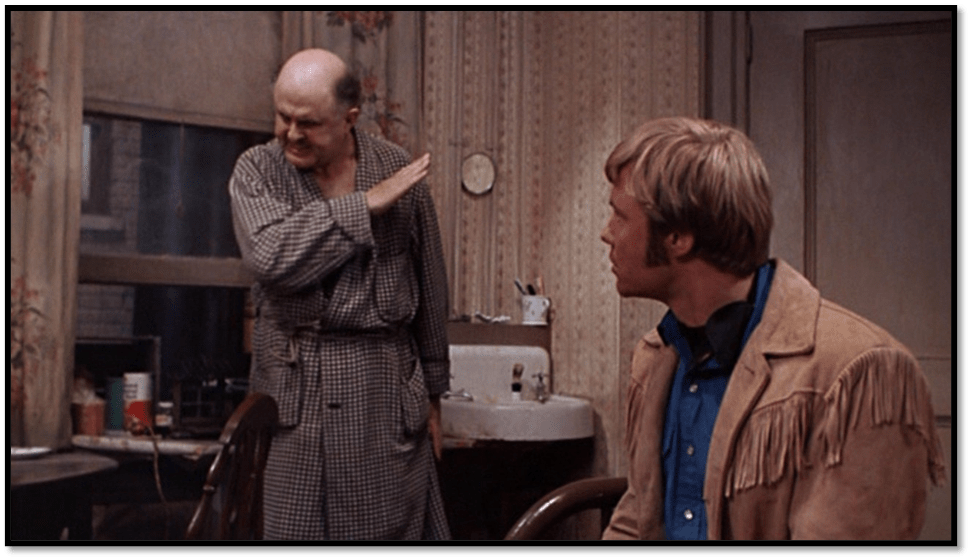

This blog queries why John Schlesinger and James Lee Herlihy respectively say that Midnight Cowboy was not a “gay movie” nor a “gay novel”?[2] Herlihy claimed it wasn’t, but the filmmakers go to some lengths to, as they think, make it less so. Schlesinger liked the one definitively active sexual queer man in the novel (there are lots of passive ‘stereotypes’ that remain however such as Townsend Locke (Barnard Hughes in the film) , the queer Chicago Businessman up to New York for a conference an a ‘little fun’. Another was the teenage boy who fellates Buck to orgasm and then vomits – on a roof space in the novel, in a cinema urinal in the film – played by young Bob Balaban in the film. His parents were mortified when they saw the film, despite their support for him as a potential actor).[2] But the active queer Mexican Perry had to go, Waldo Salt, the screenwriter, insisted to John, the producer. Salt felt the Perry section ‘unnecessary’ and that it “casts a peculiar doubt on the Joe-Ratso relationship” because he continued; “It gives too much importance to the homosexual background. … The Joe-Ratso relationship is not homosexual”. [3] This judgement is made despite the fact that it is Perry who first teaches Buck what a “hosty-ler” (hustler in a Mexican accent, I presume) is. ‘Peculiar doubt’ aside though, it is clear that by ‘homosexual relationship’ everyone from Herlihy onward (and Herlihy was consciously gay from an early age as was Schlesinger) meant when they described the relationship between Joe and Ratso as not a ‘gay’ relationship merely because neither had, nor could be thought to have in the future, sex with each other. Since then pundits have gathered in heteronormative collusion to say, like Mark Harris that ‘the movie isn’t a story of liberation, pride, or self-esteem, but of loneliness and survival in daunting circumstances’, and pointed to the ‘noxious homophobia’ about ‘faggots’ in statements both Joe and Ratso make and to the stereotypes of queer men and boys already mentioned.

But that argument by Harris diminishes the film and book as much as it diminishes reductively the definition of the ‘gay’, and is one reason I prefer the word ‘queer’. It helps little to see it as Vito Russo does in The Celluloid Closet, as a ‘homoerotic buddy movie’ for I think this too reduces the complex issues behind how men find value in each other and in their mutual-relationships to one of the explanatory erotic, without understanding the ranges in which non-binary love between persons manifests itself wherein sex/gender are not forgotten factors but are just that, one of many factors in a relationship, however important.

But it also presupposes that the Midnight Cowboy phenomenon that this blog discusses is more than a novel or a film: it is a myth from the history of the representation of queer desire in a framework of masculine paradigms that made the United States of America and all its differences. As such, it is as potent as other myths of origin of the American male and the place within that story of queered icons of the straight male and queer stereotypes.

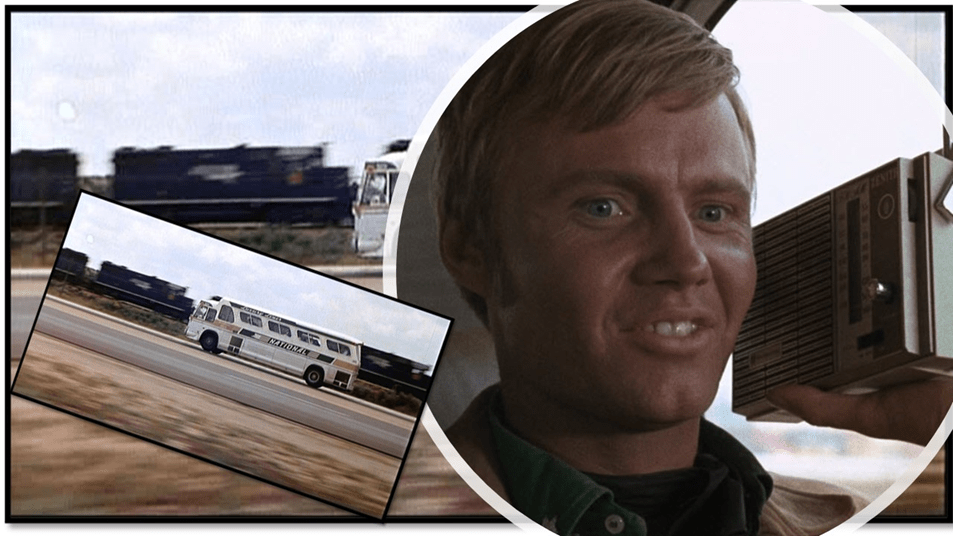

That it is about the myths of The United States itself as an entity is, I think, implied by the importance in it of the Greyhound and Buffalo transnational bus as a link between its stories, as Joe Buck journeys to his destiny on it – radio pressed to ear and with boyish hope in his smile. A bus is also the locus of its tragic ending, including one of the most ambitious shots I have ever seen; of a scene within a moving bus from outside the bus window with the reflections of a Miami set of clean white hotel fronts and characteristic palm trees through which Joe and Ratso can be seen for they are merely held as imagery on the bus window’s surface. Frankel gives an idea of how the shot was done, ‘with camera and its operator harnessed to a platform built on the outside of the vehicle and peering through the window’. [4]

Glenn Frankel in his 2021 book about the genesis and fate of the novel and film that is Midnight Cowboy tells us that the novel’s author, Jim Herlihy, preferred to travel across country in the States by bus ‘even after he could afford more comfortable alternatives’. Both the novel and film owe a lot of their power and drive to the same motif of how spaces between differences of experience are traversed and the motivation for doing so. A bus is a ‘powerful mothah’ (how a Texan would say that word probably matters – is there a suggestion of mother as well as motor) in Joe Buck’s words in the novel. Motivation and movement are aligned in it I would argue, all bound in the drive a bus represents in the novel and film. In Herlihy’s finest extended metaphor the omniscient narrator, after describing Joe traversing the bus from driver back to his seat on the way to New York as like ‘a circus performer dancing on horseback’ (one of the many horses Joe is related to as a cowboy). But Joe is, in the extension and mixing of the metaphor as it continues, not ON a bus BUT is IN it:

This great being through whose center he moved had something in common with himself, but Joe was little better equipped to think about it than was the bus itself. He felt it, though, some kind of masterful participation in the world of time and space, a moving forward into destiny’. (5)

This is a blog on the ‘masterful participation in the world of time and space’ that is the queer history of this great transnational myth of our becoming visible: it is a myth that is also ‘a moving forward into QUEER destiny.’ This is a blog on the myth of the MIDNIGHT COWBOY.

However, let’s start with the ubiquity of the bus in this myth. The metaphor of the bus itself is important, but it is the handling of that metaphor of the bus in the scene quoted above that strikes us. In one sense, it is one of the many signifiers of Joe Buck’s inadequacy as a bearer of mythic meaning. Granted tragic heroes do not know themselves, Joe Buck knows very little indeed and has next to no insight into the worlds he attempts to live within or uses to make and sustain a living. He knows he is not a cowboy, really, though he is, he claims. a ‘stud’. Nevertheless, he still has no real sense either of what makes the skill as, and equipment of, a stud a marketable commodity, as Ratso Rizzo so often tells him. His particular blankness is that concerning queer sexualities. For, again, as Ratso tells him, that is the only market parameter that gives him monetary value as a cowboy. Nevertheless, it is as a cowboy that Ratso himself begins to truly value Buck, seeing him as ‘not bad’, said appreciatively by Dustin Hoffman – ‘for a cowboy’.

Having value to somebody, or as something, is very much what this novel is about. And so many things that offer added value to persons: abstractions like a destiny, a skill (even that of deceit) or an image all get discussed in film and novel, and all seem to increase one’s value to oneself or others. The novel and film start with Joe Buck evaluating himself in a mirror (an important item in both artworks) in a way that resists reduction to any one body part: ‘For he didn’t want to wear out his ability to perceive himself as a whole’. [6] Getting a pay off from that asset, however valuable it is deemed, is another thing, as every seller of sex or even deceitful ‘bum’ like Ratso in the novel knows. Yet, for me, this myth matters because it, in an almost analytical way, shows what matters about oneself as a person sexed, gendered, and a sexual being. What Joe Buck realises is that he must not only be able to reduce himself to fragments of a body, a penis above all, but market those assets to cash it in as a commodity for its value in ‘bucks’.

Midnight Cowboy is the queer myth per se that need not identify, as both Ratso and Joe do, what a ‘homosexual’, or more usually for Ratso, a faggot is. The bus-like-brain of Joe Buck, whose very name is a variant of Stud, can’t quite compute why a cowboy image is a ‘faggot’ thing: ‘You mean John Wayne’s a faggot’, (or something like that) he says to Ratso, with his usual slow and literal precision. In fact, it’s not a bad question about the evaluation of masculine imagery, particularly given the homophobic nature of nearly everything John Wayne said in public about what a ‘man’ is and what gives him value as such. Indeed Wayne in Playboy magazine described Midnight Cowboy as a ‘perverted story about two fags”. [7]

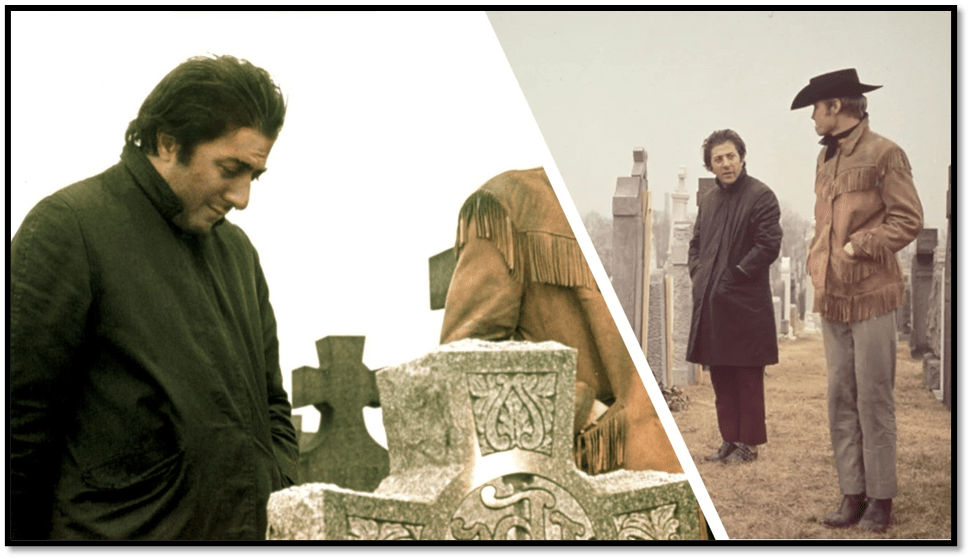

If Joe Buck never amounts to the value of more bucks than that one in his name as a hustler or a bum, both of which roles he renounces on the bus to Miami with Ratso, his value is potentially high as someone who answers to needs he cannot articulate, call it love, care, or attention to base human values. Ratso is unable to articulate what he values in a worthless father, but Joe Buck accompanies him to the latter’s grave anyway (see below), demonstrating that value accrues to the observance of honour to any man who struggled in life, however worthless by the world’s poor estimation of men by their power, status, wealth or even sexual allure and / or assets.

Buck learns to value his penis and considers it as the main asset, of the body parts he can be reduced to, in order to operate in a buyer’s market where boys for sale are two a buck, so to speak. He is been taught to do so in the novel when introduced to Juanita, a putative whoremaster and friend of the hustler Perry, who Salt cut out of the film fearing it would type it too much as a gay film, who identifies his destiny as a whoremaster’s asset, starting with the stallion equipment:

“Quite a horse, quite a horse. If I had me one like this, I’d head East with it New York City. Hear tell it’s all fags there, fags and money and hungry women. young stud like this in the stable, I’d clean up good”. [8]

Arriving in Manhattan, the penis becomes in Buck’s mind the cowpoke asset Juanita predicted: ‘Joe’s hand moved to his crotch, and under his breath he said, “I’m gonna take hold o’ this thing and I’n gonna swing it like a lasso and I’m gonna rope in this whole fuckin’ island’. [9]

Perhaps the one lesson Buck learns from Ratso, and from its first failure to perform with the ‘woman in orange’ at a party for trendy socialite’s (and played by Brenda Vaccaro in the film) is that the penis is an unreliable tool, pretty soon drained of its goods (in Part 3, Chapter 3 of the novel) and because pretty plentiful on the street of Manhattan, easily substituted for by another penis from another younger stud. In the novel, the relative worth of this member is conveyed through the relationship with Ratso: indeed, the contrast between the two males is even made in terms of penis size. On the bus journey to Florida, Ratso urinates on the bus seat and Joe in both film and novel buys him and himself new cheap and everyday clothes binning the cowboy in the process in a ‘trash receptacle’. He dresses Ratso, whose immobility is now near total, on the back seat of the bus. In the novel, but not the film, this act of care and loving attention is described:

The long underwear was wet, too,and removing it was a chore. Ratso was as helpless as an infant. Joe had never seen him naked before. his pathetic little sex looked useless, just a token affair, something to pee through. … He was like a plucked chicken, one who’d spent his life getting the worst of barnyard scraps, and finally cocked up his heels and quit. The history was written all over his body, and Joe read it well with a feeling for the sacredness of it. For a moment he saw in his mind a motion picture of himself wrapping this naked, badly damaged human child in the blanket, taking him up gently and holding him rock-a-bye and git-along-little-dogie in his lap for the rest of the trip. But he snapped off that picture fast. [10]

Ratso’s ‘pathetic little sex’ that ‘looked useless’ is a marker of why and how this relationship is never typified as a sexual (even the choice of the word ‘sex’ to describe the penis is significant for that reason). This ‘sex’ was not useless for peeing (as the scene has already shown), but is, it seems, for the penetrative sex Joe has learned to be expected of a man. The woman in orange after all had described the predicament of a hustler like Joe who fails to get an erection as, though she knows the occurrence ‘merely human’, as ‘a bugler without a horn, a policeman without a stick’. No wonder then, when his erection returns, Joe, as an act of misogynistic revenge as he sees it ‘drove at her harder, and deeper, and deeper, and deeper’ verbally abusing her as he did.

The woman loves it, just as all the passive queer men in the novel (and this is brilliantly reproduced in the film) love being humiliated and belittled by big violent men handling large penetrative words or tools that substitute for a penis (the telephone receiver, for instance for poor Townshend.

Joe’s relationship to Ratso, as he unclothes him and sees his sex is not a gay one (if we assume that involves a desire for sex) but is nevertheless certainly a queer one, involving complex non-heteronormative bonds that go beyond the buddy romance, to a relationship of bodies that touch and are touched, modelled on the relationship of parent and child here. Nevertheless, bodily acts that involve touching in every sense of the word touched, including that reflex of emotional response, without the need to invoke sexual touch, are important here.

I think our culture fears the relationship of bodily touch more than it does the reduction of love relationships to the genital, and that is characteristic of both heteronormative and homonormative relationships, for queer relationships see sex as a relationship of bodies, senses, feelings and ideas everywhere without needing to specialise it or present it as an over-scripted relationship between genital parts or the penis and another orifice capable of penetration.

It is true that Joe Buck is taught that he should see his penis as his trademark and symbol of authority and function, like the bugler his horn and so on, but I think the lesson he has to learn in New York is that sex and violence have become associated with a certain form of masculine image, one type of which is the ‘cowboy’, that equates it both with power over other people in the aim of feeding one’s own sense of superiority. Joe at moments exercises this power, with the ‘woman in orange’ and with Townsend Locke, but he as much renounces it as with the kid who fellates him but refuses to pay afterwards.

And I think this is because Buck has learned what it means to be on the receiving end of male physical violence in which the man plays an active part, the partner one of a mere hole. We tend to forget the fact that not only is the over- and overtly- sexually active girl he first loves, Anastasia Pratt or Chalkline Annie punished by local youth for being so by rape and that Buck is forced to rape her too in order for him to learn his male peer-group’s evaluation of his relationship ship with her.

In the film, however, Anastasia is not the only person raped. Buck also, as played by Voight, is anally raped over a car bonnet. Both rapes are told in recurrent flashbacks of great intensity, where Buck’s experience of sodomy is seen in his face, bent over that car bonnet, with the thrusting of a tough behind him in blurred focus. These scenes were shot, Frankel tells us, using extras from the Texan town, Big Spring, the film decamped to, and a few semi-trained actors as the Rat Pack. Sensing the vulnerability of his actual girlfriend and partner, Jennifer Salt, the daughter of the screenwriter, Waldo Salt, who played Anastasia, to the possible roughness of the young men playing those rapists. Jon Voight took the rough who had been chosen to play her rapist and Jennifer to dinner and a game of miniature golf to ease Jennifer’s fear. Of his own vulnerability in that scene, Voight and, in truth, Frankel too, stays stoically silent, like a man one might say. We know, however, that Jennifer felt that Voight was absurdly ‘overzealous’interfering’ about her ability to withstand the fake roughhouse involved, whilst not at all understanding it. [11]

The rape of Buck does not occur in that scene in the novel, instead it is part of the scene in which Perry introduces Joe Buck to the brothel-keeper-in-potential Juanita Barefoot and her love-starved son, Tombaby, where he is given to Tombaby as a cure to the later’s otherwise incurable virginity. The rape is present entirely symbolically through the feelings in Buck’s manipulated and drugged body as he feels himself thrust down and looking up from a hole, which might just be a toilet he is flushed down, by Tombaby and Perry. This experience of utter degradation that is rape itself fires Joe’s fury at the world: ‘I may be shee-it, but f’m, now on, anybody look like they gonna flush me down better look out’. [12]

Masculine experience is oft posited on the fear of emasculation, the reduction of a man to the ‘hole’ he equates the female as being in heteronormative and sexist patriarchy – a receptacle for a man. Joes’s rape did precisely that and his fear is identity with the emasculated passive gay men he meets, who revel and get sexual pleasure from their unworthiness and lack of social value being reinforced by a real man. Perry first introduces and explains such men to Joe in the novel in order to release him from his virginity, despite Perry’s liking of that very thing about Joe – a virginity, however, of a kind Joe does not understand:

“I’m afraid I’m no virgin, Perry. I am goddam awful dumb, bit I’ve fucked aplenty.

“I’m not talking about that kind of virginity””

“Oh! Well then, tell me the kind you’re talking about then. Come on, Perry, ’cause I got to learn this shee-it.” [13]

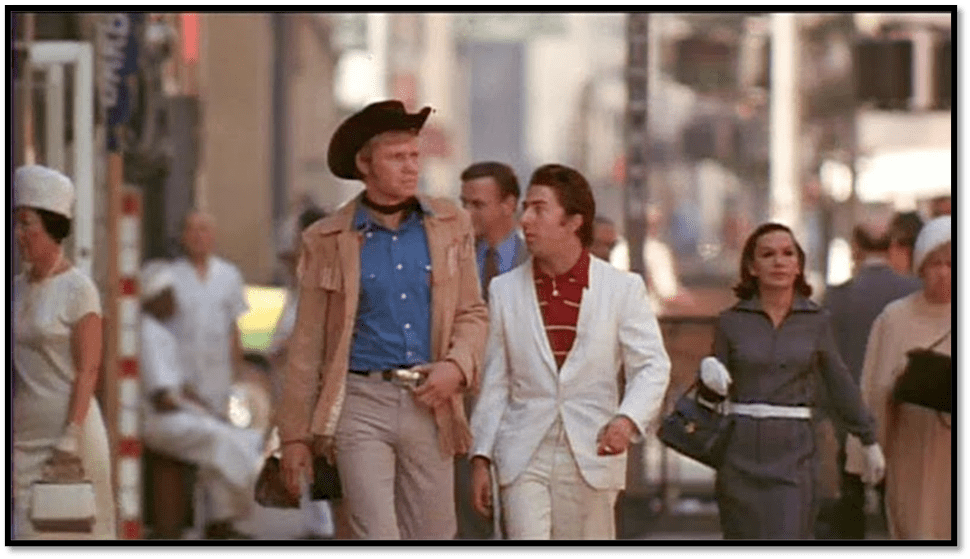

Thus, we proceed to Juanita. But that is the pre Manhattan Joe. Once there, his most important relationship will be with Ratso. See how we see them first in the film – a pair of buddies but with Joe hopelessly dependent on management, a clue Ratso soon picks up.

If the relationship with Ratso begins like the abuse of a simpler man by a more sophisticated one, so beautifully done when we come across Dustin Hoffman dressed in white and raising himself from his small stature by big talk, the fact is that this is playacting cannot be sustained. We see Ratso fail to maintain his dignity, constantly calling to be named Henrici, or if that is too much Rico, rather than Ratso. Ratso impresses everybody in his hubris against a taxi-driver when he upbraids the moving vehicle by asserting ‘Im walking’ as if what he were doing trumped the action of anyone or anything else. This scene is not in the book, but Herlihy loved it when he saw it first. Dustin Hoffman claims he ad-libbed it in confronting a real taxi on the street, although Frankel tells us that the scene was written into Salt’s script before it was shot and that the taxi-driver was an actor.

Ratso’s first scam is to secure twenty dollars (a lot then) to send Joe to Mr O’Driscoll, a supposed manager of rent boys, but in fact a kind of perverted converter of the sinful who asks boys to get on their knees with him in front of a flashing Madonna in a closet. Ratso organises this by using street telephone booths as his office.

That O’Driscoll is getting kicks from this that are undoubtedly sexual is clear. This old man is fed youth by Ratso.

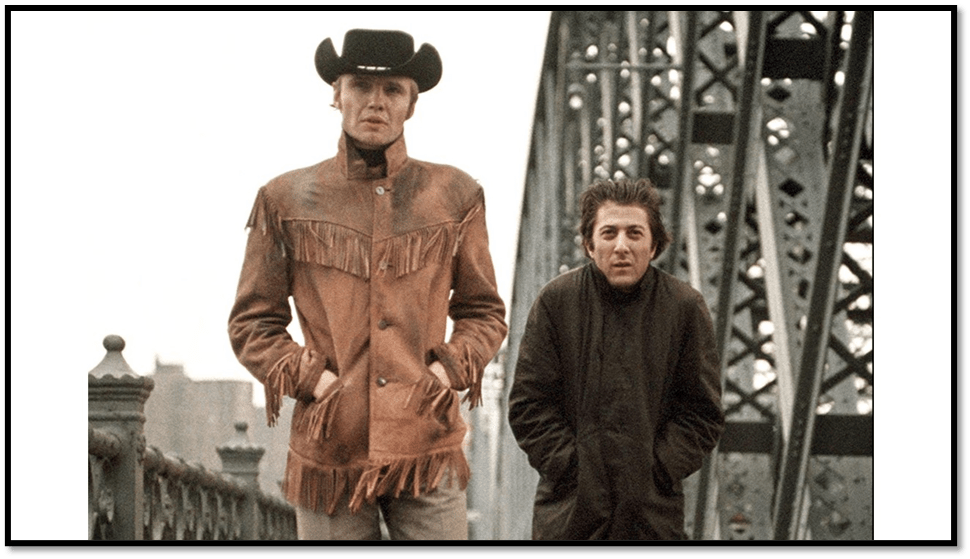

Nevertheless, despite the scam and his fury after it, Joe clearly feels an affinity and closeness to Ratso, that it is the job of this film’s filmgoers to explain satisfactorily to themselves. Obvious to us that Ratso is a con-man who has otherwise little going for him, Joe has built an attachment that will not change. The film conveys this in moving pictures with the language of looks and permissible proximities between male bodies, as in the mirroring of hand gestures below and the confidence in the indirection of a gaze that remains mutual in feel however its object is not shared between them.

This mirroring continues even when circumstances for the duo deteriorate as in this famous shot on the bridge.

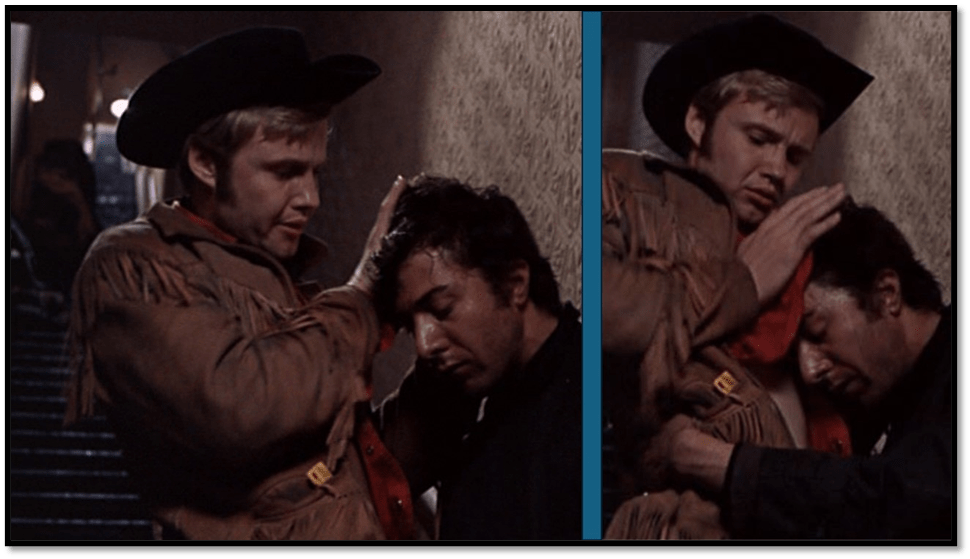

The scenes in the X-flat, a flat in a building about to be demolished that had an X made of tape on its windows to stop shattering by nearby demolition blasts, are pure magic in creating and building the relationship and seeing within that relationship, Joes’s transition to a need to care for Ratso, to respond to the younger man’s evident need. In the still below, he comes into the flat to find Ratso, having lost mobility and seriously ill. The flat itself was a real one, but threatened by demolition earlier than expected, its interior being was stripped and moved to a studio and rebuilt with the original smells of stale urine, and everything else ‘authentically grungy’ still in it, in order to draw an even more authentic feel of the men acting to care for each other in a state of near total degradation.[14]

This is not an ‘odd-couple’ story, for its analogue is a world where wants and needs are the prompts to manipulations. The novel carefully inducts Joe into a world where what you want or need needs to be paid for, and Joe intends both to be wanted and desired, and paid for to boot. he starts by thinking this the easy thing Juanita promised for a ‘stud’ like him. His first ‘conquest’ though, Cass, played brilliantly by Sylvia Miles in the film, is herself an ageing seller of sexual favours. She enacts terror, awe, and moral collapse when asked to pay Buck for the sex they have, eventually turning the tables to get twenty bucks out of him. Yet Joe is telling the truth when he says he enjoys the sex and wanted it. There is that about him that finds it difficult to connect the wants satisfied in himself, another or both, and payment for it.

Indeed, if Joe achieves this at all it is by needing money to meet the needs of another, another one can no longer not believe he loves – for what else might love be – another man by the name of —– Ratso, of course. The case of Towny is tragic and that of the teenage fellatio-giver quite comic. But that he should do this for Ratso is the more remarkable in that Ratso pimps Joe so that they both can eat. Joe suffers because everything that might answer a human need is being as he sees alienated, in being transformed into cash, from human warmth. Here is Ratso at work in the novel:

Sometimes, against his own better judgement, but in an extremity of hunger, he would arrange for Joe a fast five- or ten-dollar transaction in which little more was required of the cowboy than standing still for a few minutes with his trousers undone. But these unhappy conjunctions left joe in a depressed and disturbed state of mind. He felt as though something invisible and dangerous had been exchanged, something that was neither stated in the bargain nor understood by either of the parties to it, and it left him sad and perplexed with an anger he couldn’t find any reasonable place for. [15]

That depression and that anger is caused by a perversion of capitalism – a distaste for the commodification which genital sex causes when no other part of the self than his penis is involved. Now, I have said that the love that develops between the men is real and queer if being queer is only what is not heteronormative. I have hinted that it is about the care of the body and whole self mutually in the film, but I do not think that this excludes body. It is just that it doesn’t depend on part of it alone. I think the film’s actors develop this in ways that the novel could not, especially Dustin Hoffman. In the novel, love develops out of Joe’s need to realise his needs in the care and ability to hold, for a time, another. Hoffman makes this apply to Ratso, too.

In the scene in which the two visit a party run by real actors from Andy Warhol’s art institution, The Factory, who agreed to appear in the film more or less as themselves, Ratso begins to collapse as he ascends the staircase. Joe holds him – the hold is functional and necessary. Hoffman, however, extended the hold by exposing the flesh of Joe’s torso, pulling him in with his arm around him and lowering his head to the exposed torso. Buck looks down with extreme concern – half holding Ratso back, half supporting him. It is as if Ratso’s need for Joe was flowering into physical love and that Joe reluctantly is responding. We need not think of this as sexual but it is a beautiful moment. Frankel tells us that these extensions and deepening of the loving mutuality in the relationship, born in improvisation whilst shooting, really excited Schlesinger and Salt.

I think these moments in particular made the final scenes on the bus to Miami possible. Herlihy made the last scene explicable by virtue of our growing ability to see the deep need and its beauty in Joe Buck to actually care for another, though that other be now dead. And he traces that need right back to the men’s first meeting: ‘He put his arm around him to hold him for a while, for these last few miles anyway. He knew this comforting wasn’t doing Ratso any good. it was for himself’. [16]

Both dead and alive as Ratso, Hoffman plays these as if not only comforted but loved, and returning that love, though neither would articulate that, even to themselves – and if so, only as something unenduring. But it does endure. It is the memory of the film, more even than the novel. Rarely can a film do deep material better than a novel. In this case however, it really does

Read Frankel’s book. There is so much more in it that I have suggested. But more than that – revisit Midnight Cowboy. The novel is much better than Gore Vidal thought it, but if pushed at least, re-see the film. It is a small miracle of art finessed to perfection of collaboration. More than anything, forget the obvious ways in which this book and film plays with the homophobia of deeply repressed characters, though it could do with balance from a queer person who thinks themselves worthy. It celebrates the fact that we are a complex community, differentiated as well as having commonalities as queer people, and admitting that some of us are deeply damaged and some few, very few, downright warped. But we deserve our differences and respect from each other as well as from others, although others still unfortunately hold a whip hand to which they feel entitled.

With love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] Glen Frankel (2021:280f) Shooting Midnight Cowboy: Art, Sex, Loneliness, liberation and the Making of a Dark Classic, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[2] ibid: 215

[3] ibid: 140

[4] ibid: 231

[5] James Lee Herlihy (2003: 97) first published 1965 Midnight Cowboy London, Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

[6] ibid: 5

[7] ibid: 304

[8] ibid: 79f.

[9) ibid: 99f.

[10] ibid: 252f.

[11] Glen Frankel op.cit:236 – 238.

[12] Herlihy op. cit: 87 (for fantasy rape, see 85ff.)

[13] ibid: 70

[14] Glen Frankel op.cit:211f.

[15] Herlihy op.cit: 170f.

[16] ibid: 258

2 thoughts on “Why did John Schlesinger and James Lee Herlihy respectively say that Midnight Cowboy was not a “gay movie” nor from a “gay novel”? This is a blog on the myth of the MIDIGHT COWBOY as discussed by Glen Frankel.”