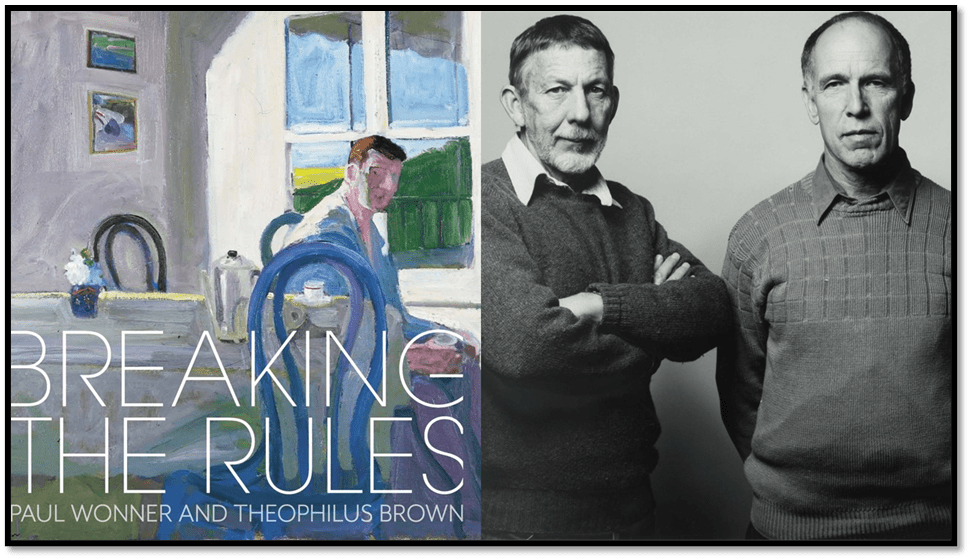

In the Introduction to the catalogue of the recent exhibition devised by the Crocker Art Museum Breaking The Rules: Paul Wonner and Theophilus Brown, curator Scott A. Shields says these queer artists who lived together in California and elsewhere were ‘nearly always described as followers rather than leaders’. And yet the evidence suggests otherwise. Whilst this has been explained because their background was that of the Academy rather the Art school, Shields says that Brown knew that, in being ‘a homosexual couple’, they would ‘remain, at least to some degree, outsiders’.[1] To what extent do queer people embrace being secondary and / or a ‘failure’.

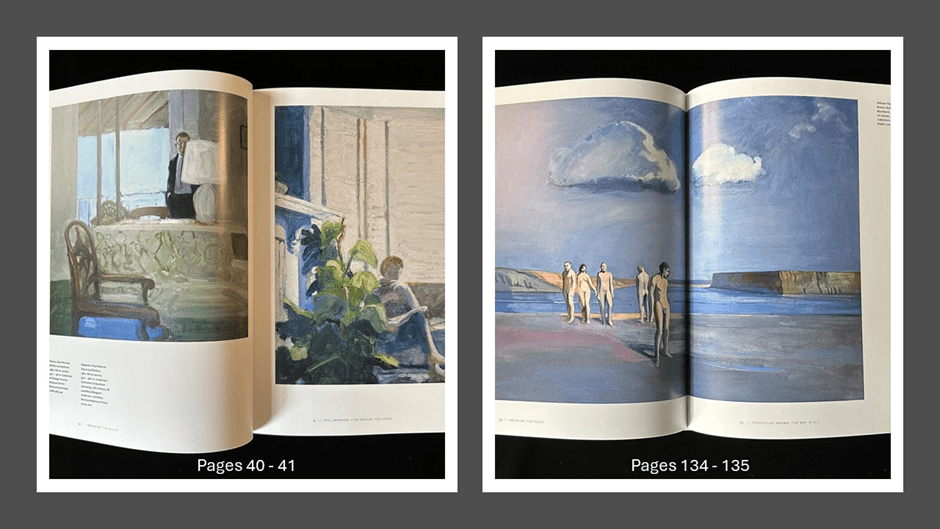

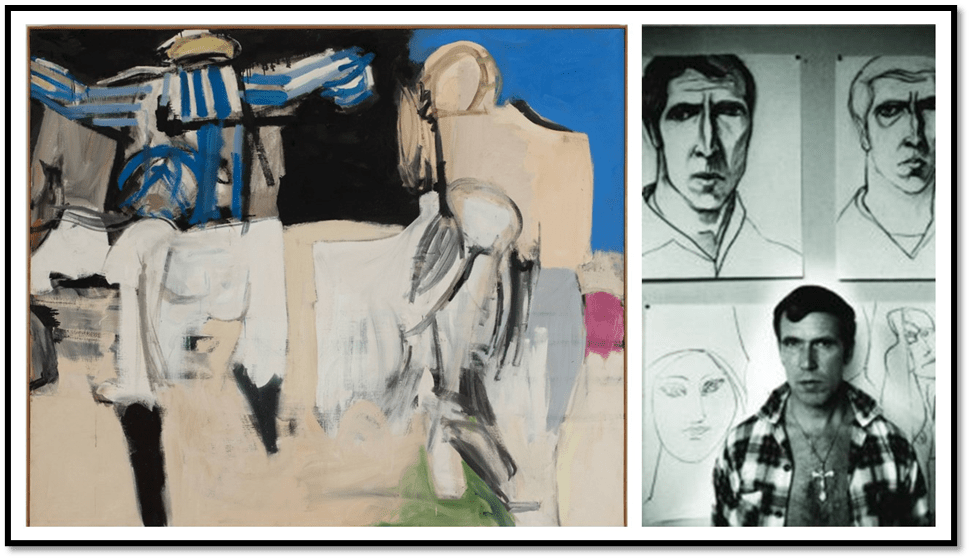

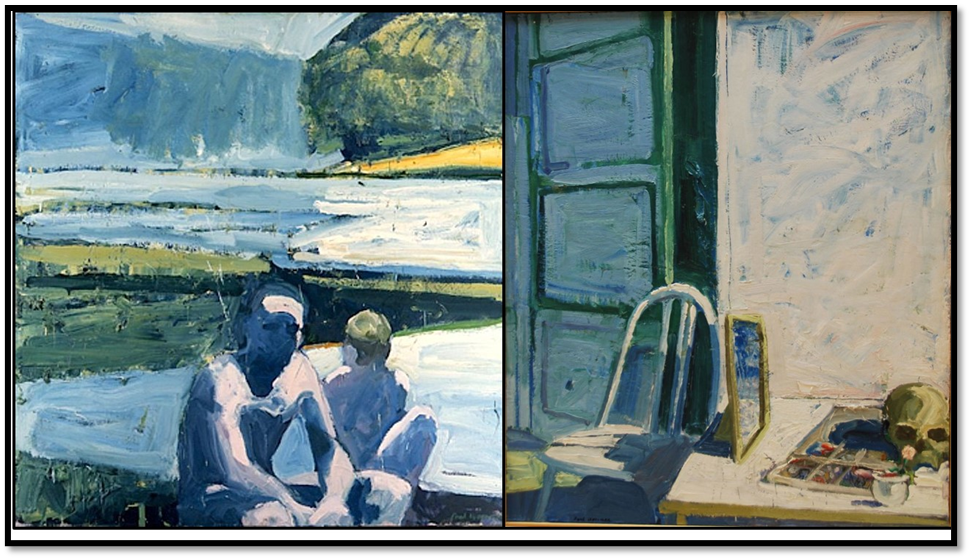

Let us not forget that this blog owes everything to the catalogue of an exhibition that I will never see in the flesh. However, it is a catalogue that might also be called a Duogram (if such a genre – or word – exists and I think it does not) as a version of the artistic monogram- a consideration of ONE artist – for this book, after a stunning introductory rationale by curator Scott A,. Shields and personal recollections of the couple as artists and friends by Matt Ganzalez, is, in effect, then divided into a monogram section for each artist – each including the moment where both men met each other (Wonner thought Brown a ‘snob’ and resisted him for some time) and their union as living partners if not as consistently sole sexual partners. Before I wander off into my argument, it needs to be said that this is a magnificent book, beautifully and comprehensively illustrated, though everyone may find a personal favourite painting omitted. You can see this by a taste of two folds from the book, the first with two pictures by Wonner, the second one of Brown’s that crosses the centrefold. Strangely enough, the pictures show contrasting themes in queer life that are actually explored by both artists, each with their own very distinct emphasis, style, and mode of design.

The Wonner pictures (Malibu Living Room (1964) and Figure by Window (1962) respectively) emphasis themes of reflective isolation that both painters dealt with but that Wonner made his own by the creation of a scene that looks like a blurred reflection in a mirror. In each case the interior has an engaged and contemplative subjective interiority: details of faces get obscured by objects and lighting (shade in the first, glare penetrating a window in the second), whilst thought processes are conveyed by the unconsciousness of a viewing gaze, gesture, posture. There is engagement of the figured in something or nothing, in a matter or task that may not matter – in both artists a neglected ‘open book’ may take this role but here it is an abstracted diverted gaze or a newspaper idly gazed upon, though not held. In Wonner, the paint marks themselves create both detail and obscurity – as a pattern unseeable in a tablecloth or the positioning and dynamic of the hands in the sitting figure, whose sex/gender seems merely accidental.

The Brown painting (Nudes on a Riverbank 1971) is a landscape with a grouped set of figures, whose purpose and overall relationships to each other is difficult to discern, as if their nudity, which they seem not to find significant, is not so but should be accepted as the figures accept each other. One male nude with his back to us seems as if he were holding his penis to urinate in the water, though no other persona gives him a second glance. The one female nude holds her hand out to a male in her vicinity, it seems, but whether that hand clasp is returned is not seeable. Features are homogenised or at least deindividuated, though the isolated figure at the front, possibly Brown himself, has a distinctly less fleshly physique.

Colour patterns are as important as patterns of space between the figures, and the tonal variations are beautiful – a wash of pink in the foreground being particularly beautiful. The bodies are balanced and patterned too, apparently by the sun or shaded as it falls on their stance relative to the sun. The text explores the thesis that such open and wide boundaried paintings are images of a utopia of mutual acceptance or “what I would like to be doing, the kind of life I would like to be living’, as Brown said in agreement with that idea. However, as Shields says, not all figures are ‘happy or engaged, and some are very much alone’.[2] This is another theme both painters explored, as we shall see. Groups, especially make groups, mattered tonthese painters. Why?

Let’s take, as Shields does, as an example of male groups in their lives, the grouping both painters found themselves associated with: the Bay Area Figurative Artists Group, as it is sometimes known. Even the Wikipedia entry on this movement (see last link) places Wonner and Brown in a later ‘bridge generation’ dependent on more purist primary or ‘first generation’ returners to the figure from abstract art like Richard Diebenkorn, Elmer Bischoff and David Park, all heterosexual, seen as the prime movers, which Shields with very good evidence disputes.

Indeed, the Bay Area movement is sometimes spoken of as formed when Richard Diebenkorn (or Dick as they knew him) sought warmer studio space with Wonner and Brown (who were both salaried at a University). Gonzalez records how both Wonner and Brown recalled Diebenkorn saying he was ‘freezing my butt off’.[3] Later Dick brought others into the larger studio space available. Nevertheless critical opinion and Wikipedia discourse upon the group using parameters set in 1989 by the first Bay Area Figurative Art 1950-65 exhibition. Wonner and Brown were seen, and perhaps in part were encouraged to see themselves subsequently as outsiders even to that group, or worse as secondary followers of it.

What they added was talked about as a possible unnecessary excrescence by Maria Callaghan, who said they ‘expanded the style to incorporate autobiographical references and symbolism’.[4] One can almost hear the sigh that identifies all that self-reference with ‘queers’, oft thought stereotypical narcissists by virtue of the same-sex attraction at all – as if we liked only what is THE SAME as us.

That groups, especially those in a queer pairing, like these two painters found themselves in, settings or work projects that are heteronormatively defined, were not easy places to be is suggested in the introduction, from which I take my title quotation. The nuance the queer couple found about the way this group worked is silently recorded in their contradictory words about it cited by Shields. Compare the following citations from Brown, which I have placed in a table for easy comparison:[5]

| The joys of a group | The downside of a group |

| I liked all those guys enormously and I thought it was unlike New York, where there was a lot of rivalry between painters. | David, Elmer, and Dick were very important to each other in a way the rest of us in a sense were peripheral. |

That the quotations came from Brown matters. He, unlike Wonner, had a background among painter groups and their affiliations as movements. In his early career he met Giacometti, Duchamp, Rothko, Guston, O’Keefe, and painted in the studio of Léger. He declared William and Elaine de Kooning friends and thought him ‘beautiful’.[6]

Wonner never quite identified with all that, and I suspect that is why he thought Brown a snob at first. But I think both learned from each other and in supporting each other in lives lived together but also separately, with different partners and friendships in queer communities. Such communities, in all their fragmented variations that sought not to be noticed in the mainstream as a self-defence in line with heteronormative requirements, lie behind the painters’ representation of groups. Their painting explore,in my view, and I think theirs’ too, a queer perspective that required they painted in ways others found impure. Hence let’s turn briefly to queer theory.

A stunning book of 2011 by queer radical academic Judith Halberstam says that academic disciplines like art history and cultural studies and their dependencies and satellites in the established national media tend to act, as James C. Scott explained, to make individuals ‘see like a state’. Such a way of seeing ensures that ‘certain ways of seeing the world are established as normal or natural, as obvious and necessary, even though they are often entirely counterintuitive and socially engineered’.[7] He goes on a little later to embellish this description:

For Scott, to “see like a state” means to accept the order of things and to internalize them; it means that we begin to deploy and think with the logic of the superiority of orderliness and that we erase and indeed sacrifice other, more local practices of knowledge, practices moreover that may be less efficient, may yield less marketable results, but may also, in the long term, be more sustaining.[8]

That perception of others from radical queer theory and from reflection on queer experience (for Halberstam is ambiguous about the Academy) will be used later to show that how it allowed them a fine revenge, if in a series of coded ways. Brown insisted that even his queer followers would not buy “anything with a penis attached to it”. When they refused coding in their painting, they generated subjects that made art critics flinch. One such critic, Caroline Jones, comments that far from courting ‘the aesthetic tradition’ of the nude as it was once seen as different from the naked body, Brown in particular showed nudes both female and male that are not only just “naked” but also “corpulent. And disquietingly erotic”. Others go on to say his eork as a “voyeuristic quality”.[9]

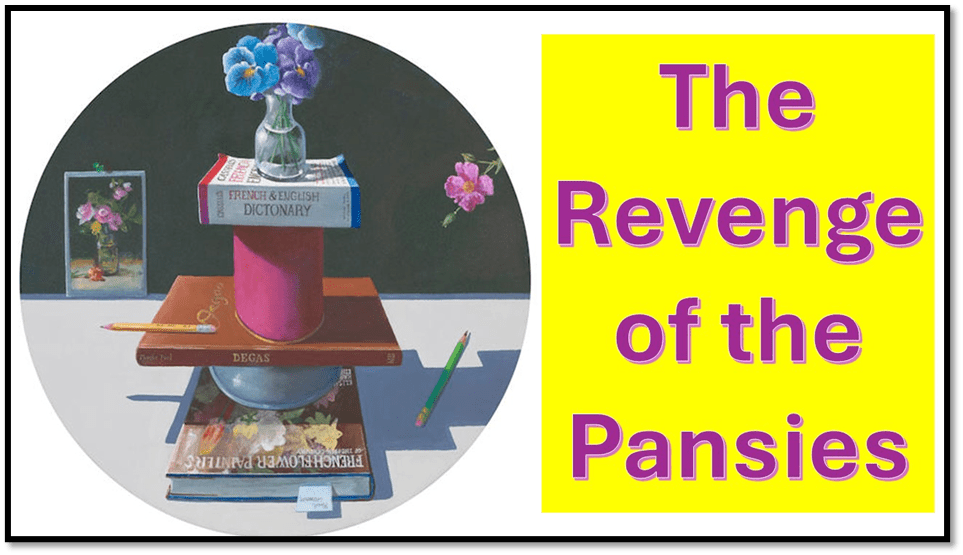

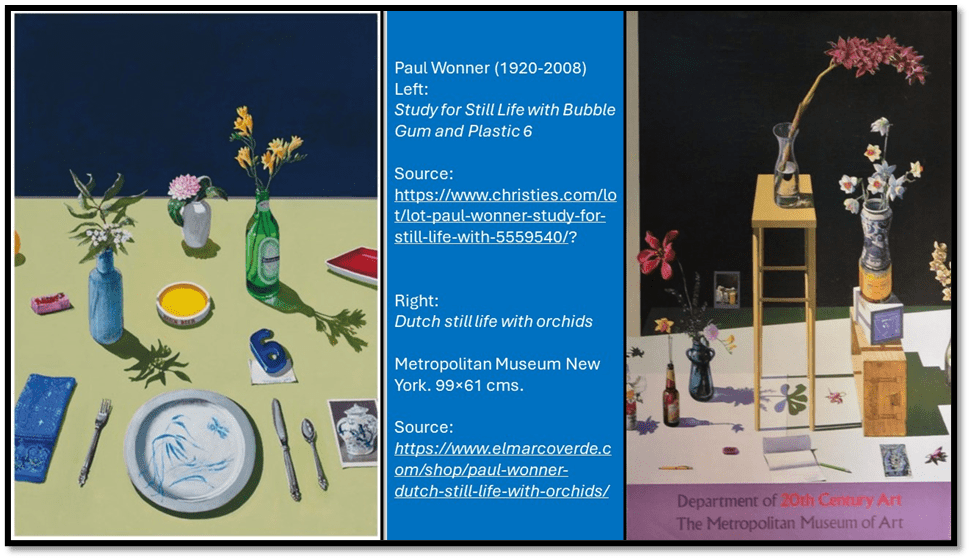

But the coded resistance too was quite wonderful and perhaps had its own way of taking revenge at queer artists being forced into secondary and marginal places. Ignacio Darnaude in a summary of the book, with his own sly additions, in The Gay & Lesbian Review speaks of Wonner’s ‘frequent coded images of pansies’. He continues:

The word “pansy” is, of course, one of the many anti-gay slurs. In his striking French Still Life (1990), a vase with pansies stands proudly above books depicting French and English artists, implicitly claiming that queer artists are at the top of the artistic canon.[10]

Hence I have labelled the collage in which I feature that painting’s reproduction Revenge of The Pansies. Of course, we have to have fun and the truth is more nuanced – I will eventually argue that, far from becoming absorbed into the competitiveness of the institutional art-world, rigorously heteronormative in its public face especially amongst Abstract Expressionists, like Jackson Pollock, it preferred a model of retreat and collaboration and a painting that allowed worldly claims and titles to go elsewhere, whilst their painting followed innovative tracks to high standards that made heteronormativity look like a rigidity of mannerism as behaviour or description of life or art.

The play with almost surreal patterns of tonal variation, sometimes passing itself as the cast of light and shade or foreground and background, extends to the hyper-precision of the pencils laid at a slant or across the perspectival field with shadows in the case of the one on the left-hand side that makes us query the placing of the unnaturally static lighting implied – like that of theatre. If pansies are at the ‘top of the pile’, secondary to no-one in France, even Degas placed above the mere genre of French still-lifes. All the pansies need is a good well-thumbed French-English dictionary.

I am extremely pleased to share that chuckle of silent revenge – though convinced that the heteronormative world still holds all the cards in its hands and is used to winning. Nevertheless, I think that there is a more nuanced position we can take in evaluating these queer artists. It is best expressed by Wonner, a man deeply suspicious of the hierarches implied by winners and losers and evaluation by order of crossing an arbitrary winning line. That suspicion made him value himself as a queer man after all the difficulties, including those in the sometimes turbulent relationship with Brown, because he could step aside and set his own pathway of artistic trial and error, failure and unnoticed success:

I think being gay was the greatest thing that ever happened to me in my life. I think that it gave me a direction that I might not have had otherwise, and made me not afraid of being an outsider and being by myself. And [it] also gave me a lot of courage to just blunder ahead and do things … and often I was very fearful.[11]

Without a doubt, Wonner’s exaltation of ‘being gay’ is not because it made him a success in the terms of the American Dream of his age. He lived comfortably, and though his sexual life was fraught with Brown, they considered themselves ‘family’ to each other – a condition that implies as much tension, as they willingly said, as it did comfort, but was based on a presumption of loyalty to each other as persons, each very different to the other, at its base. In effect, if human happiness is in this state, it is not by virtue of utopian communion or community but by virtue of a state of estrangement and lack of external guidance or overt support. Wonner is ‘l’étranger’ of the Camus type: an outsider without the accompanying existentialist philosophy (or not in a way publicly shared) to bolster it. It is the path of what Halberstam calls the ‘queer art of failure’, I would argue, where achievement is another facet of what a world that is hostile, if sometime with a smile on one of its own faces, would call ‘failure’ to thrive, compete and sell, but which in Halberstam’s adopted term is a refusal to ‘see like a state’.

The relentless trend of the mid-twentieth century to portray the lone white middle-class homosexual, and potential sad case of completed suicide (though such tragedies did happen) lies too near this estranged figure of the queer. It is a figure which haunted the Report of the Wolfenden Commission in the UK 1957. Films aiming to make the homosexual a figure of sympathy such as Victim, starring Dirk Bogarde, or The Killing of Sister George with Beryl Reid, promoted a ‘political’ message for law reform and attitude change. However, they also tended to show the queer man as not only isolated but scared, and if given the sympathy required in no way different (sexual practice in private ruled out) from other middle class persons. Similarly in the USA, Tennessee Williams showed queer men as surreptitious mockeries of a sexuality between that of women and men, as in The Glass Menagerie, where isolated sexually repressed women (or blatant women such as Blanche Dubois in A Streetcar Named Desire) could pass as models of the fate of men interested in sex with other men that was forbidden. Williams’ real identification with his mentally ill sister Rose, an early victim of lobotomy treatment, is often pertinent here, as in Suddenly Last Summer.

It was a trap this coding of men as women and as both as victims – it robbed queer people of a life that was lived not only alone and in private but as social beings with other queer people as a matter of choice rather than ghettoization, which is how the Mattachine Society in the USA and The Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE) in the UK saw the situation. The latter aimed for a normalisation of the identification of queer men and women, a normalisation that would allow a blending in of difference and the need for differentiation otiose. For queer people of the period, this aim was one that denied sociality, which homosexual law even after 1967 would see as a social problem. There was a danger in queers congregating in each other’s company, the Wolfenden Committee concluded. There was a danger of the presence of queers in exclusively homosocial settings such as the army they further concluded.

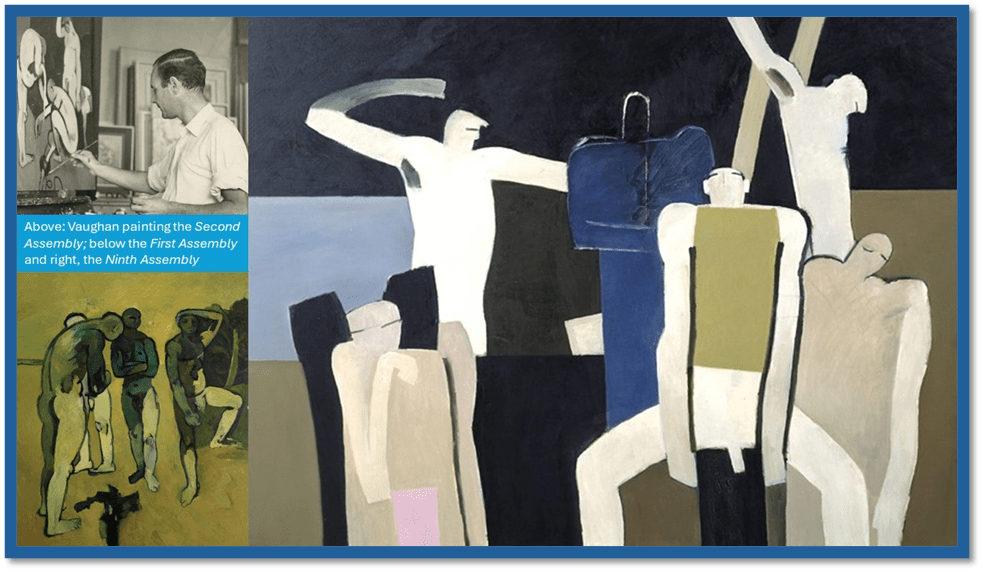

For artists this caused interesting approaches to the representation of figures in representation of groupings of same-sex figures. It is a problem that Keith Vaughan encountered in his experience of non-armed conscription (he was a conscientious objector) and in choosing to paint in such company using men as his sole models in the Second World War. It launched him on a career where the painting of all male groups became for him a distinct genre, wherein groupings of naked men stand together only partly and formally related to each other and sometimes reduced to abstract patterns, when they interact as shapes or in ritual action the relationships are queered from recognisable norm. He called them his Assembly Paintings, see examples below.

I mention Vaughan’s Assemblies here though merely because this tendency is in both Paul Wonner and Theophilus Brown too. Sometimes these figure in the latter painters have what seems to be a purpose in their waiting – and because Wonner was increasingly likely to take risks they seemed almost descriptive transcriptions of cruising grounds where there is no visible interaction other than grouped forms of passive waiting – as if for another not yet there and excluding each other. For me, Wonner’s paintings of Figures in a Park have a sense of sociality and isolation – of a relative openness broken by largely unseen barriers. In a sense, I would say these paintings are a compromise formation between the desire for open sharing of difference and its occlusion by external norms that engender fear and sometimes unnecessary distance, physical, emotional, and cognitive. People who are used to being judged undesirable, judge each other harshly.

There is always an excuse for the homosociality in a public space. In these late (the first reproduced from the book and dated 2006, the second between 2003-6) Wonner pictures, it is a dog that must be walked, although few are seen actually walking. Rather, dogs become a focus for a male group. The example in the book is better, although I love the use of the blurred reflective and distorting surface in the collage above that I also use. Both, however, homogenise faces and are overtly, especially the first, sexually suggestive, often with help of rather fleshy and embodied sinuous trees. Both pictures seem masked, not only in any subjective implication as to the motive of gathering of these men but their posture in stance or position as a recliner on the grass. They, I think, follow another way Wonner picture masks the purposes of art with those of communicating themes of queer homosociality in his attempt to create a version of Manet’s Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe.

Wonner’s version has sensuous fleshy trees that congregate and interfuse in the shades between them, and men either at a distance or an excused proximity, the excuse being the rather puzzled dogs who look out at us. The naked woman has a possible girlfriend in the lake, also naked. The effect of a male gaze, except as it be on males, is disarmed, whether sexual or aesthetic in this picture. If anything, it is the returned gaze of the figure masked in sunglasses that captures the ‘gaze’ of the viewer. The queer sexualisation of a painting – or rather a contemporising of the queerness of the original – is both mask and celebration of figurative art returned to a function that challenges norms and boundaries between categories in sex or art

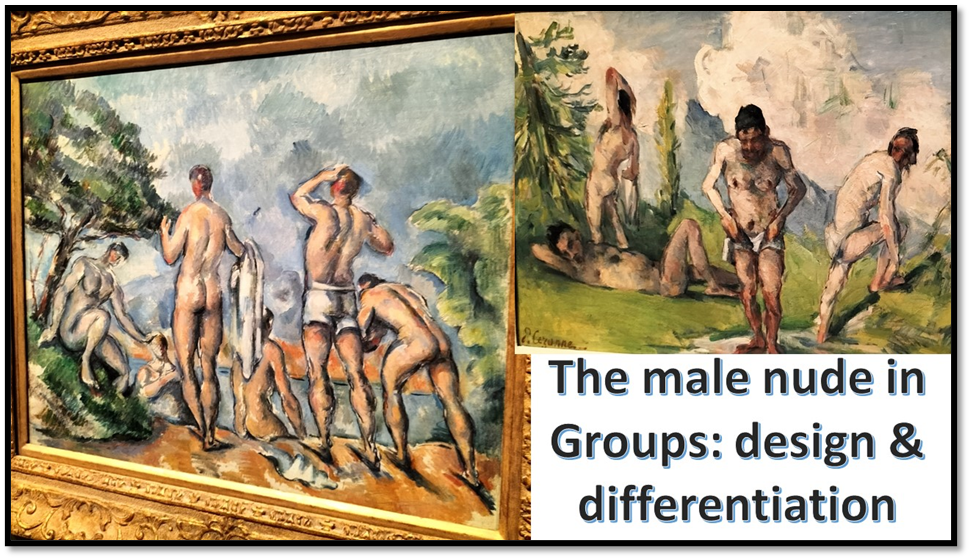

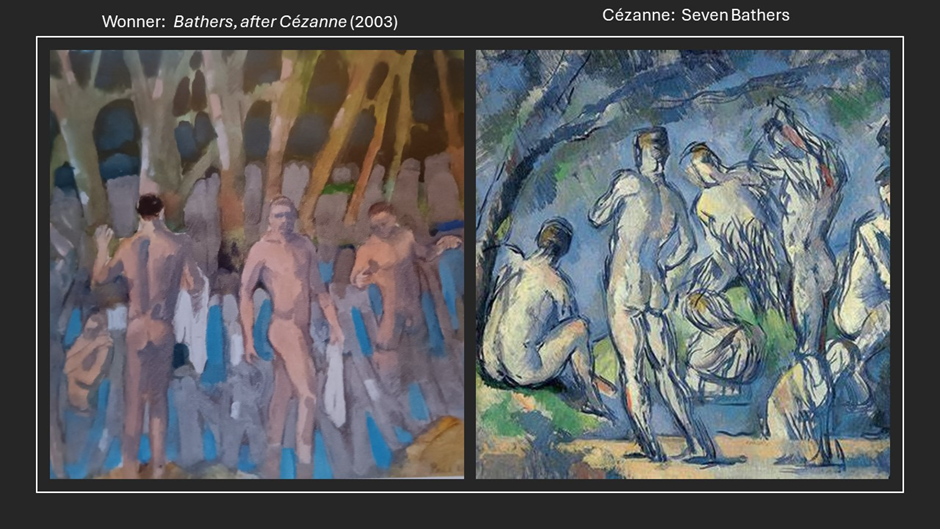

One could say the same of Wonner’s impressive attempt to honour Cézanne, for he takes the repressed homoeroticism of the originals and returns them to us with greater obviousness of sexual and queer reference. There are issues in the master regarding the representation of the homosocial group in its flesh. Even now I giggle at attempts to render these pictures by renowned art historians as a reflection of the artist’s belief in the health and hygiene properties of nude bathing. Such ideas sustain advertisements not art. When I saw a retrospective of the great artist I thought this though about Cezanne’s male nudes (see my full blog at this link):

Hence it is the individual male nudes that stand out in this exhibition, especially my favourite one below, although the action of tentative stepping in the process of bathing seems a stock Cézanne trope for it occurs in the group example (the one on the right) above. We are less interest in a static take on male nudity but rather in the dynamism of male bodily motion, even in the most tentative of actions.[12]

I offered the collage below in illustration thereof.

But in the collage below, see how Wonner’s male bathers are even more clearly posed so that we see all around the male body. The trees fuse via the paint in a manner that blurs the boundaries of objects and things in the interflow between branches, arms and different kinds of trunk. The men are doubled in their reflection in water. A contrapposto figure in the centre is flanked by frank vision of anus and penis, although I doubt whether these bodies better Cezanne’s sinuously beautiful nudes.

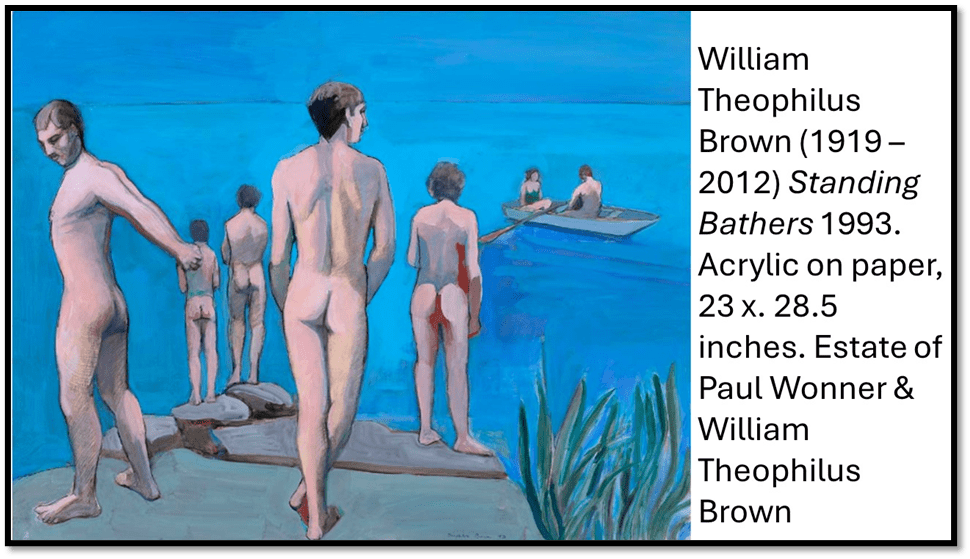

The same influence plays on Theophilus Brown too, though his bathers seem more remote and the figures tend more to the symbolic than sharing the story of how in practice men meet together. Sometimes the symbolism what Caroline Jones and others identified as quoted before above, as “disquietingly erotic” and with a “voyeuristic quality”.[13]

Standing Bathers however is as much perhaps an icon of Brown’s boldness as it is pertinent to our theme. It seems to me a kind of debt of honour to Wonner who had addressed himself on a Christmas card, says Darnaude, as “Paul Cézanne”.[14] And it is I think a lesser achievement than Wonner in this area of male bathing groups than Wonner’s. Yet it does fascinate as well as perturb, particularly those splashes of bod red which seemed to scar the depiction of both the space between his left arm and torso of the stander facing away from us to our right. The suggestion of blood is unmistakable but not representational, else why in the space under the arm.

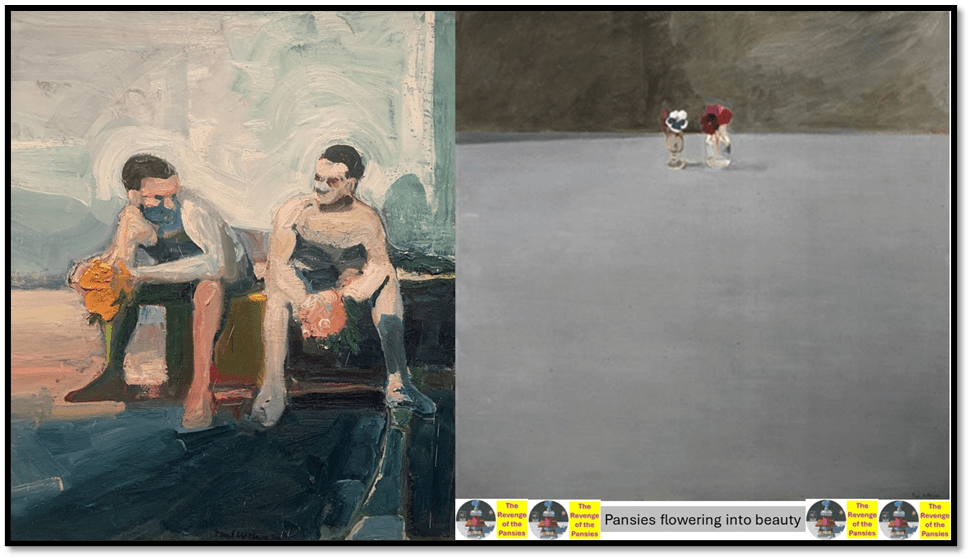

The aim seems to be to create an image so ‘still’ that it stands away from life drawing, which Wonner’s groups do not. Indeed we know Brown used pictures from nudist magazines rather than models for pictures such as this.[15] Indeed I guess, on my own part, that as Brown used static groups like this more, the more he seemed to be interested in the tension between and within individuals male bonds, in pain and unpleasure as well as the utopian in these bonds, the primal honesty to be expected of a truth-teller, for queer people are not made happy by positive thinking alone as Halberstam insists (see my blog on this at this link).

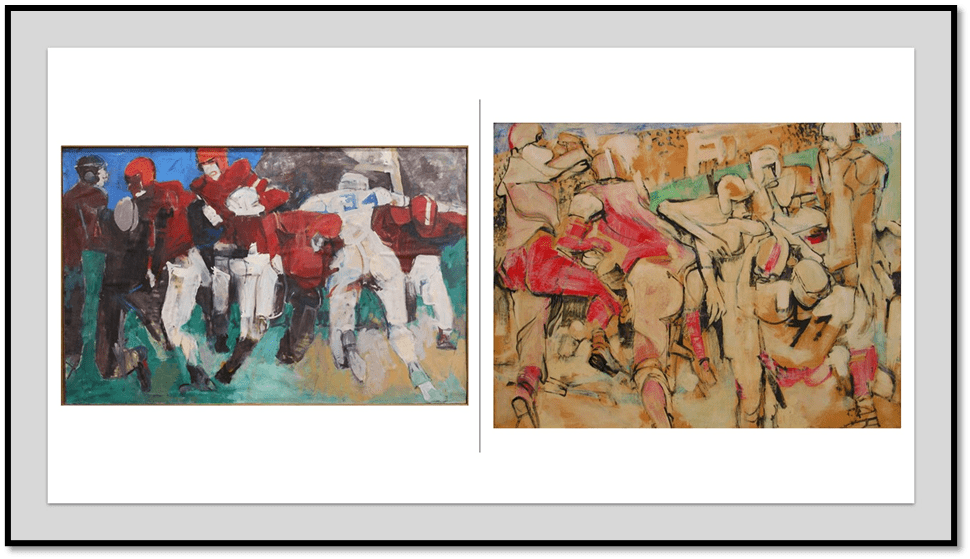

Brown had been idealistic about all-male groups once: when he studied them as an emblem of both male and inter-male action using sport, especially football, as an emblem. Darnaude thinks this was because he wanted to picture male queer desire as an achieved union in active touch and play between ‘men in close quarters in a way that was acceptable to heterosexual viewers’, but I find that assumption of the cynical too simple. Though true that he did not even understand the rules of the game enough to represent teams in the accurate coloured jerseys worn by each team, this can also be because for him the use of colour in action was his attempt to bridge the fashion for ‘action painting’ inherited from Pollock to a semi-representational depiction of the flow of desire between men that was just not meant to happen when men followed rules and norms.

The integration of form and colour into an abstracted design mattered more, even in the more realistic of the two pictures above (on our left), than the accuracy of mimesis. What excites is the fact that individual bodies become difficult to distinguish from each other, limbs flowing into limbs – how unlike the Standing Bathers, whose distance from each other matters. Shields thinks that Brown soon found the idealisation of male physical bonding impossible to sustain even as fantasy, as he became less interested in men in groups doing things together than in individual men doing nothing but attempting to be what they were in all the complexity that involves. He correctly says the use of action was an aesthetic choice where the football was a “pretext for the act of painting and the rather adventurous manipulation of pigment”, in Brown’s own words.

As he moved to the depiction of men in isolation, even when in groups, his view of the ‘action’ pertinent for paint to capture was internal action in the man not between men. The critic Gerard Norland said that starting from The Referee (1956 see below) the interest is in stopping physical action on the field (as the referee does) and internalising it so figures are “ psychologically charged with an ambiguous and elusive significance”.[16]

Whether this was because of what he learned from the more stoic Paul Wonner I do not know. Wonner loved drawing men together in paint, though often in couples, but they are separated from each other by psychological distance, with backs turned to each other sometimes symbolically. Likewise, he loved empty scenes of isolation where a chair stood for the absent figure. The River Bathers (1961) is beautiful and integrates figures in nature, but it also fissures figures from each other. Shadow exaggerates, individuates, and distances the figures, though there is an attempt of the pigments representing body to touch, The flow of visible paint forms enclosed daubs, wide and boundaried. It is beautiful and reflective, but it is a sad pastoral, not a joyous one. And if Death and distance can say ‘Et in Arcadia Ego’ it is not surprising that an empty chair (anyone reminded of Fritz Perls here) has a skull next to it holding down a daily newspaper in Mirror, Skull, and Chair (1960-62). And how opaque that mirror is with interaction of blue and white wide flows of disturbed paint.

Even men together that might be Wonner and Brown as Shields suggests in Two Men at the Shore (1960) are cut apart by dark pigment, though their heads touch – the paint creating each face merging. The picture seems to be of cerebral union failing at the body, as each figure encloses into itself. It is a beautiful painting.[17] Wonner’s individual nudes sometimes see split and blanked by their environment. It is a picture of failure that resonates with the success of capture of psychological truth regarding human estrangement and queer off-centredness.

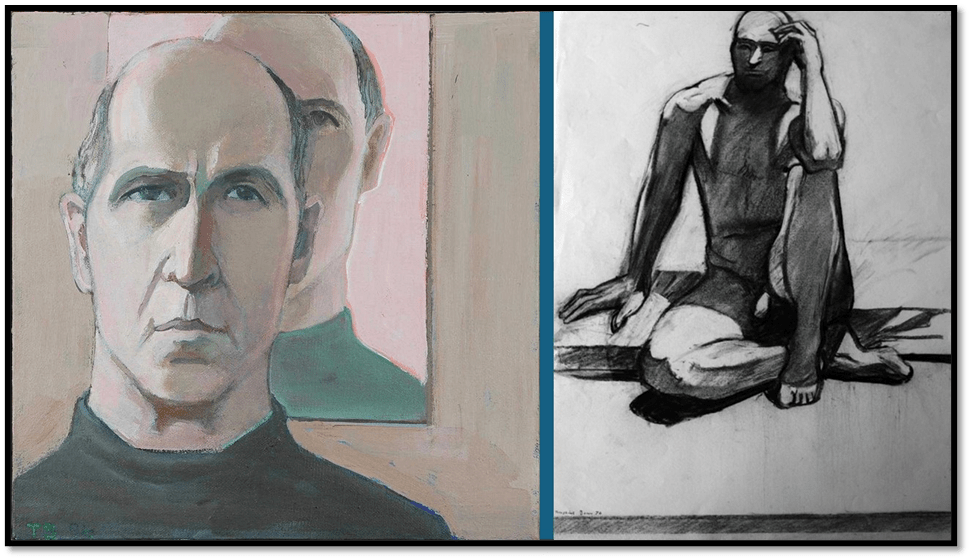

In Brown there is a very conscious percipience. Only he could do a double self portrait where the self is angled differently but is reduced to the gaze of very intelligent eyes. Even his nudes do that. The eyes vie with a defiance that the gaze of the viewer be not drawn to the penis of the nude – made luminous as it is here with what isn’t an accident of light. For Brown the puzzle of sexual physical attraction had to be solved and honestly. The self-portrait works because at first we mistake the portrait behind the figure as a mirror – but some mirror that does not capture the viewer but the artist gazing out again.

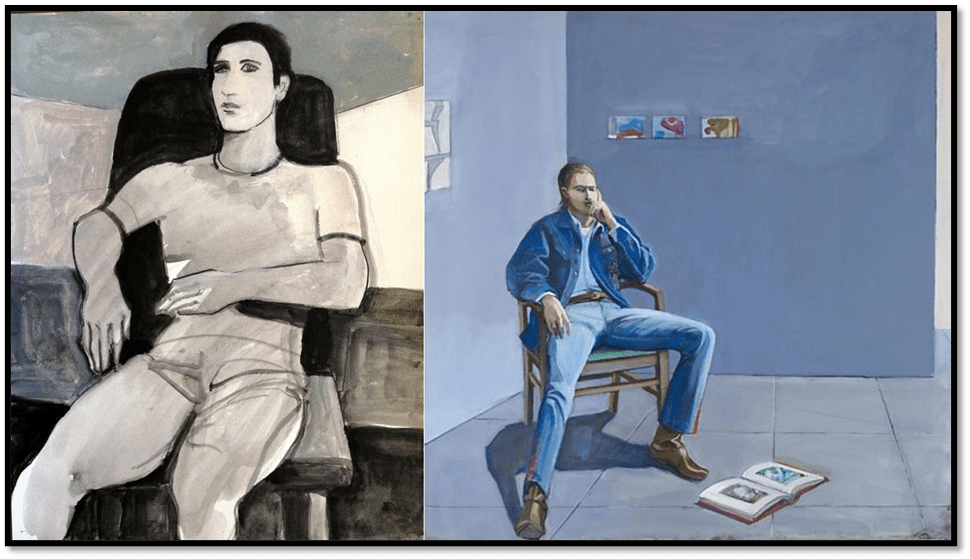

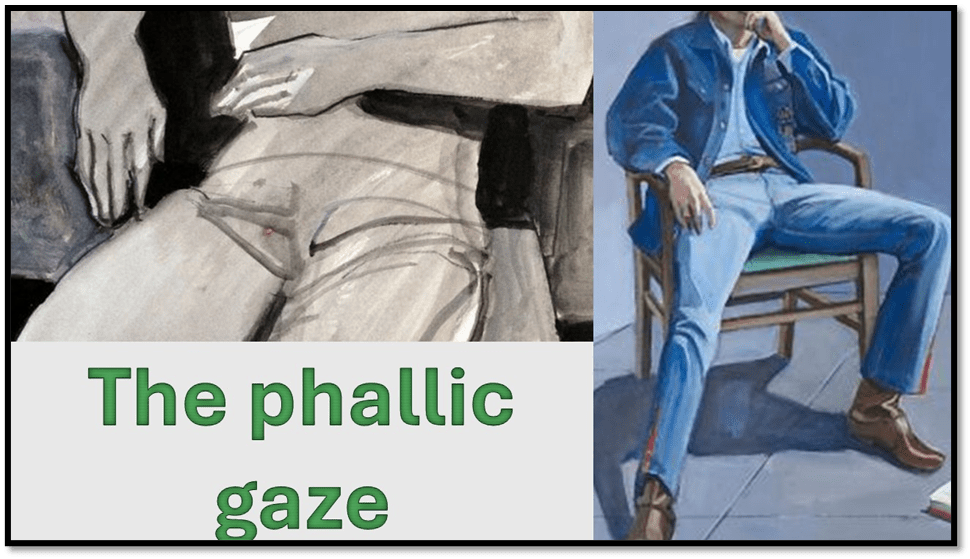

Brown’s singular portraits concern some people because of their honesty about what makes the male body physically attractive even down to the signalling penis. How long does anyone notice either clothed portrait below without being drawn to the stylised bulge in the clothes the penis occasions.

On the right is Jim Christansen (1970). Stuffed with motifs like the small miniature scenes (his own fantasy paintings) and an open art book, these openings in fact only make more prominent the very masculine opening and spreading of the legs, and the forward motion of one foot. The married artist was not gay as I believe but was notorious for being banned as a children’s illustrator because of what people saw as the sexual context of his fabulous pictures. Are both men through reduced by a phallic gaze. My own feeling is that there is no reduction here. The stylised bulge is seen as part of the saccading of the eye back and forth, into the illusory depth of the portrait and out again. It is this which emphasises the peripheries and the multiple foci, though still largely physical than imaginative in the young man – the muscled arms.

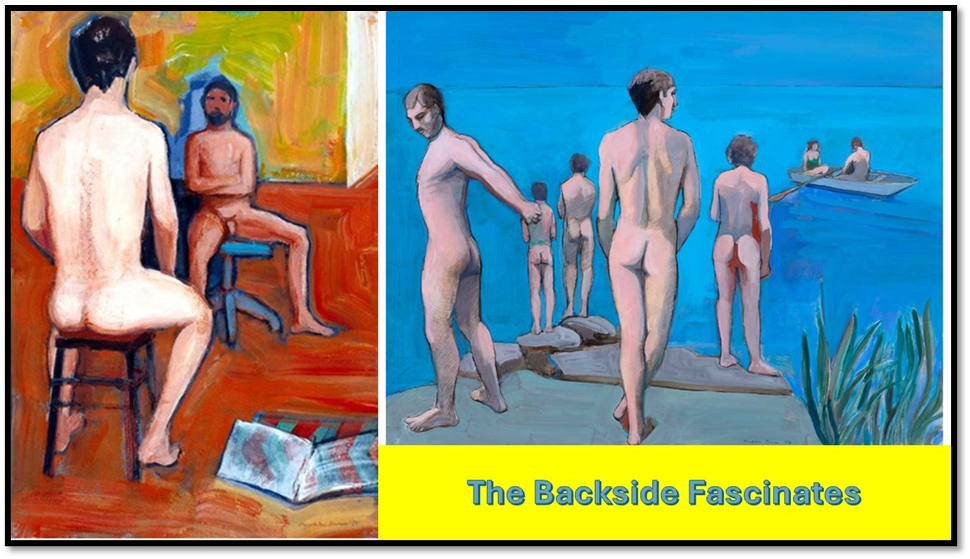

I think the point is the honesty that refuses to not admit that that the phallus is an object of desire for some. The prominence of it in our desire depends on the training of the eye to use the fact that it looks everywhere but not neglect this fetishisations of body parts for they integral to desire in their variations. Likewise the interest in the backside view of men in both painters. Below, on the left Brown makes anus and penis meet as alternate foci, though when we withdraw we notice this is an artist and model motif, of which both artists were fond as a motif from classic art made his own by Picasso but too often as a generalisation for universal heterosexuality. I have already spoken of how the back views of the standing bathers stills things, but one point of the painting is how the back side view of the whole body view is reduced to the backside (the anus) in focal vision and patterning thereof. There is a flow of the eye, in a wave in that panting ended in that troubled red crack of the anus.

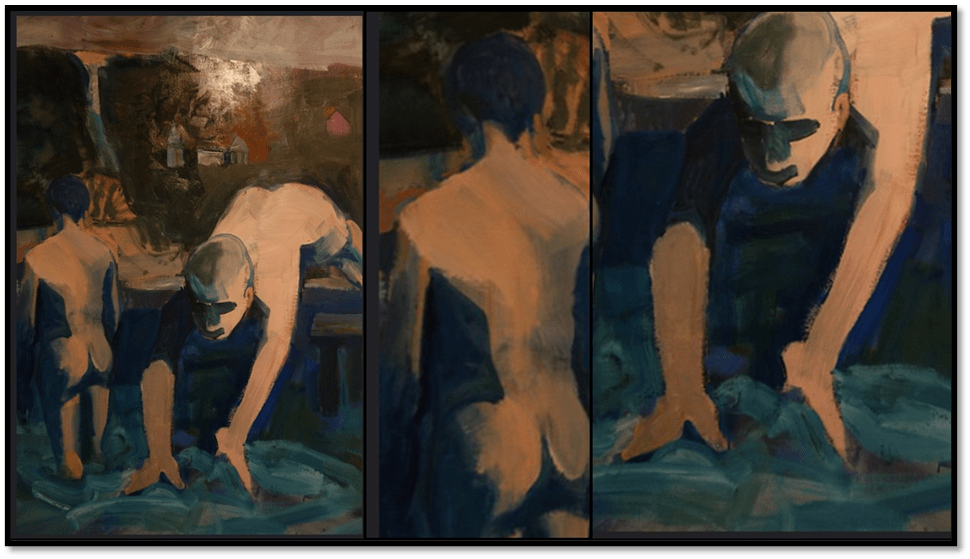

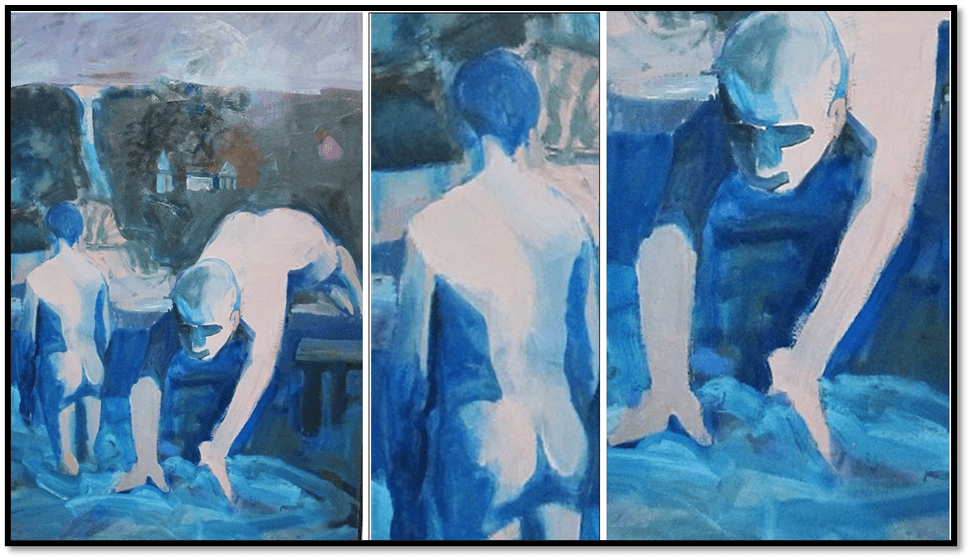

Brown’s greatest picture in my view is the 1961 The Muscatine Diver. This is a painting not unlike Wonner’s couple paintings. One figure backs on another and they are distanced from each other in several ways, but one is also active and the other passive and reflective – that one looks away from us. I am tempted to see an allegory of the relationship here. Brown diving into experience, Wonner standing in it and thinking. But this is about views of painting about which both agreed. Painting is an engagement with pain, Brown here uses the swirls and daubs of a Wonner painting but with more dynamism – even if that means there are fewer attempts at straight laterals and verticals. The diver seems to capture the swirls of paint in his hands as he dives. It is an embrace of what is lost when action painting is foregone. I copay it twice because my sources were coloured so differently. Neither Weill be true to the original but it does make a point about our reliance on the different offerings of reproduction over ‘originals’.

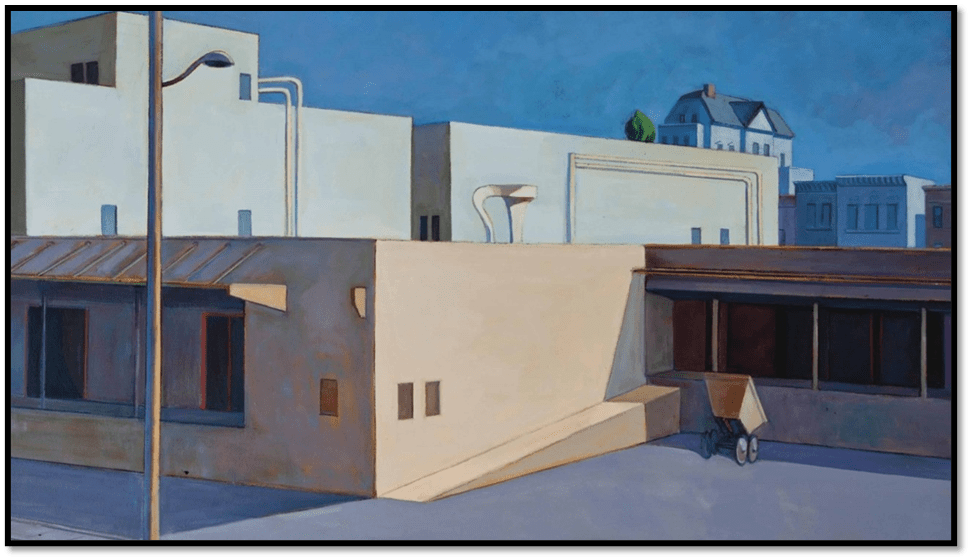

I just wonder at that beautiful painting. Wonner and brown are complex artists. They experimented with different signature genres. Bot used landscapes with figures as well as direct figurative groups and individuals but, for a period Brown became interested in industrial and urban landscapes so stilled they seemed distorted and surreal, as did Wonner become interested in still lifes stilled beyond even the Dutch models he looked at.

Two issue leap out in these interests. First they both seem interested in isolation – of things in a still life or the emptiness of a venue that should be full of life to perhaps mount a wider critique on object and production centred values. You decide, Secondly both use it to see why distortion matters in painting and why it is used. Brown said, as cited by Shields that all his pictures, thought he was speaking of these landscapes ;begin with distortion, which for me is a psychological necessity, something I create on purpose’.[18] The point may be for us. Yes, I see, But what is the purpose? I am just on the start of a journey with these painters but I suspect the purpose is to test the limits of the perceived real – and to enable us to see distortion is a matter of order, form and pattering of objects and figures in space, Those distances are determined by artifice not reality and hence art strains to show that queer vision is artistic vision, a vision that goes beyond the bounded categories in the world like male and female, straight and gay and into the reality of our variations. Artifice is not art but you can make an art out of artifice to make that very point.

But I want to end on a positive note despite my dislike for the positive thinking fallacy. Earlier I spoke of The Revenge of the Pansies. Pansies can be beautiful even when they are tiny in tiny jars swamped by a grey pace of distance around the,. However small, colour triumphs in Wonner’s 1968 still life Glasses with Pansies. There is no triumph here but there is an insistence on the need to continue existing despite the grey expanse. Sometimes Wonner turned his interest in renewed masculinities into a joke as in the series Seven Views of the Model with Flowers in 1962. In one of these bunches of flowers project forward as a substitute for the hard phallus of stereotypical masculinity. It is a beautiful dream.

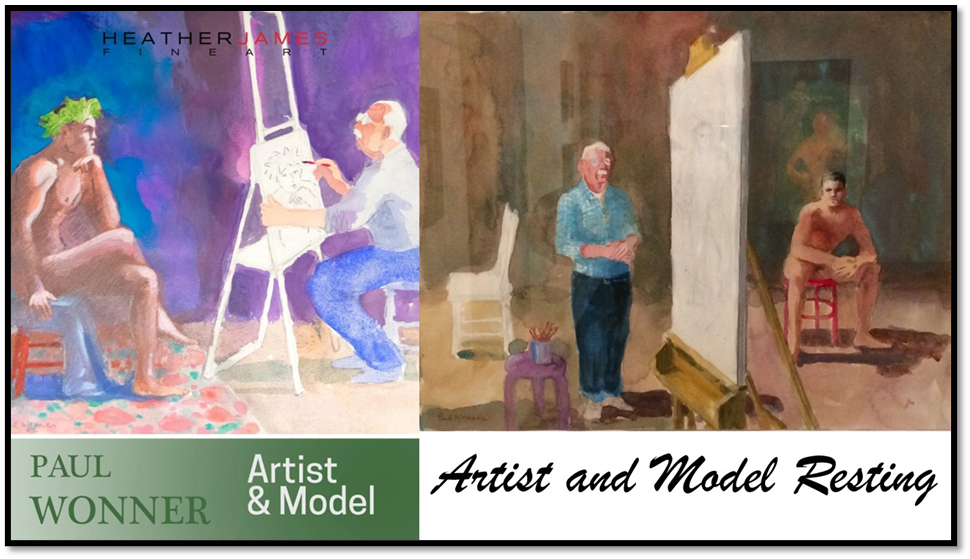

One of the best jokes of Wonner’s lie in a series of pictures of the Model as Bacchus (not in this catalogue) but they match another series (beautiful indeed) of Wonner’s Artist and Model fantasies. In each Wonner is an old man, still interested in male bodies but taking his gaze away from beautiful models of classical masculinity, which the intensity of concentration on art puts in the shade for him. There are better examples in the book. But there you have a reason to read it now. Do read it and gaze.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

XXXXX

[1] Scott A. Shields (ed.) (2023: 21 & 31 respectively) Breaking The Rules: Paul Wonner and Theophilus Brown, Sacramento, CA & New York, Crocker Art Museum & Scala Arts Publishers.

[2] Ibid: 133

[3] Ibid: 13

[4] Ibid: 22, 28

[5] From ibid: 31

[6] Ibid: 113f., 117 for snob.

[7] Judith Halberstam (2011: Loc. 244) The Queer Art of Failure Durham (USA) & London, Duke University Press. Kindle ed: therefore Location numbers not page references are used, which are, of course, approximate.

[8] Ibid: Loc. 256

[9] Scott A. Shields op.cit: 131

[10] Ignacio Darnaude (2024: 14) ‘Figures of the Bay Area’ in The Gay & Lesbian Review [Vol. XXXI, No. 2, March-April 2024] 12 – 14.

[11] cited Scott A. Shields op.cit: 98

[12] https://livesteven.com/2022/12/04/on-seeing-the-tate-modern-ey-cezanne-exhibition-on-the-29th-november-2022-and-the-salutary-effect-of-being-much-more-puzzled-about-this-artist-by-seeing-their-pictures-as-they-were-painted-an-a/

[13] Scott A. Shields op.cit: 131

[14] Darnaude op.cit: 13

[15] Scott A. Shields op.cit: 126

[16] Ibid: 120

[17] Ibid: 62f.

[18] Cited ibid: 151