On seeing Robert Icke’s Player Kings: my thoughts and feelings on the delight in being wrong and having the wrong expectations and being surprised by true artistic teamwork.

There I am in the collage above waiting in my stalls seat (A10 it was) for the play to begin. The theatre had much grandeur to offer and I examined it as I waited, encased in what felt like the interior of Shrek’s castle painted for its owner a rather glaring green. As the programme notes on the theatre make it clear, this theatre, one of the many grand old theatres (like the Sunderland Empire), clawed into the Ambassador Theatre Group (ATG) and serving mainly the tastes of audiences in masses. As Sarah Bleasdale, General Manager of the Theatre, says this play (‘a new version of Shakespeare’s Henry IV by award-winning Robert Icke’) is ‘somewhat different from some of our usual programming’. It is a theatre now aiming at a taste for musicals and comedies (mentioned for this year are ‘Sister Act’, ‘Peter Pan Goes Wrong’ and ‘The Wizard of Oz’ with Jason Manford. Tuned now to the mass audiences that such monstrously large theatres are equipped to seat, though not necessarily to create comfort for, staging this play feel’s like a return to the days when on school trips from Holme Valley Grammar, I saw Olivier and Joan Plowright play there in The Merchant of Venice and The Master Builder.

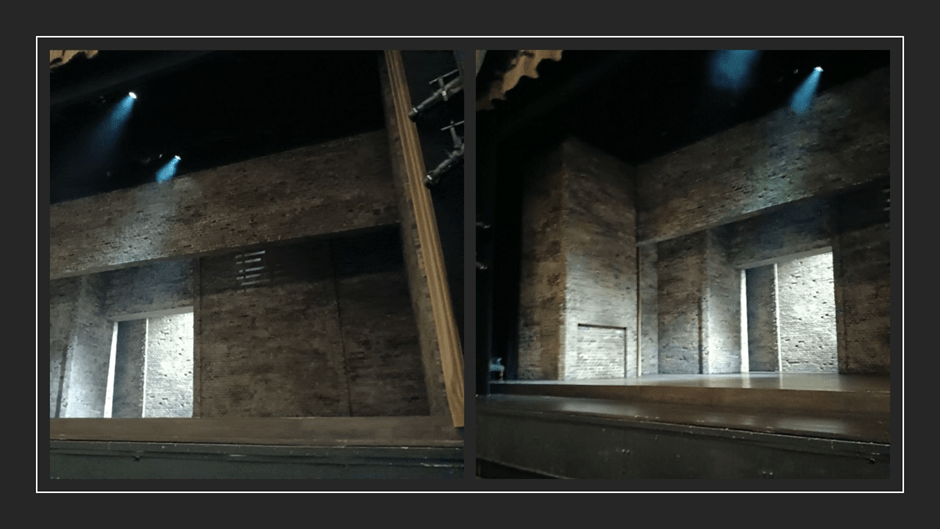

But theatres such as those in the ATG have proscenium stages that are like those of no modern theatre, where the grandiose barriers to audience ‘involvement’ have been stripped, from the huge decorated and Baroquely sculpted proscenium frames to the huge safety screens and fire curtains that hold the audience back from seeing the set design basics and sometimes the actors before a play starts. And then they was the vast machinery for lifting and dropping screens and stage ‘flats’ that made up a set. These theatres are equipped for the extremely large and have a stage enormous enough to hold it, together with ambitious gantries of lighting for creating spectacle. This theatre has a huge safety screen (entirely black without the quotation they used to have on from Hamlett: ‘For thine especial safety’) but it was used only during the one interval between, roughly, the contents from Part One and Part Two of the Henry IV plays.

We saw the open proscenium and the basics of the set – made up of layers of what seemed to blank brick walls from the start, we saw the size of the area which actors could and would fill. But I intend to say more of this later. First, I wanted to return to my own expectations of the production, that were spectacularly wrong, and why that might be so. In brief, I was so wrong because I thought without any great knowledge of the direction of ambition of play adapter, producers and designers like director Robert Icke and his partner designer, Hildegard Bechter, both stunning artists and stage team leaders in their own right, whose working collaboration is beautifully described in a single fold of the programme (see it below).

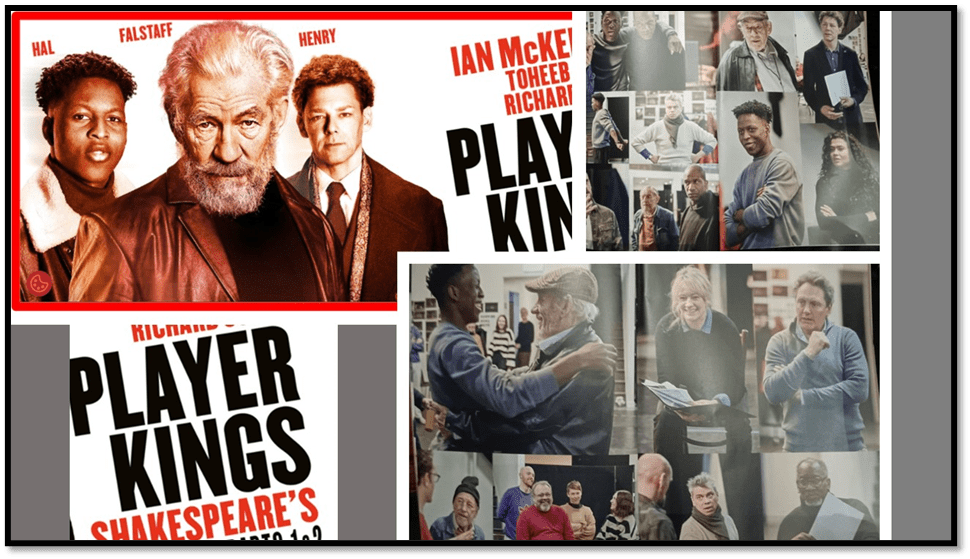

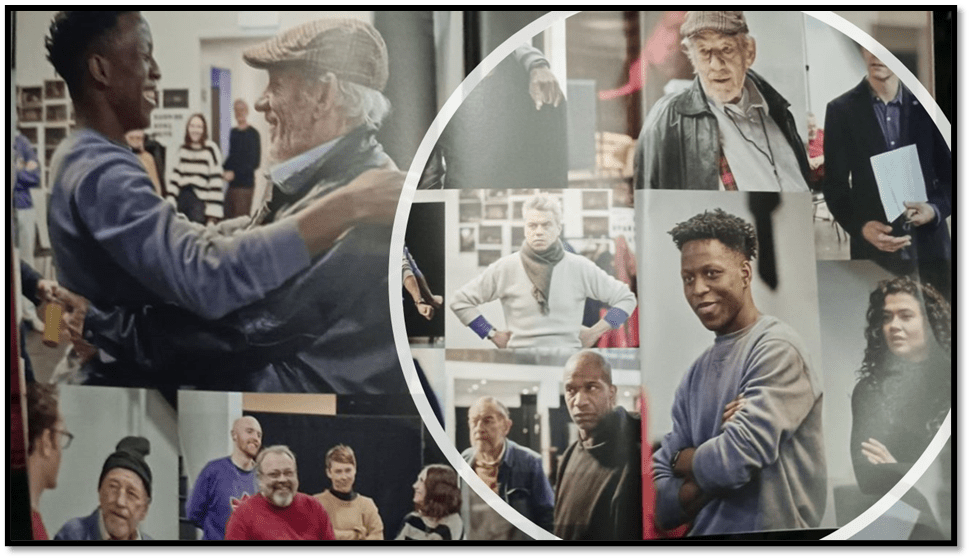

Another feature of the production style though is that collaboration is very much the feel of this production, and that whatever the innovative direction from above, it seems to use a style that uses every ounce of what entire creative teams of individuals – actors and technicians stuns. As for the actors, we sense that in the rehearsal photographs in the programme, and although the star system survived to ensure McKellen was duly recognised this was an ensemble where every performance in every role was notable individually and fitted with an overall collaboratively held idea. As a result certain roles, such as that of Mistress Quickly, as played by Claire Perkins, emerged from the production as monumentally important in their function and setting of theme.

I think I also got it wrong because I failed to take into account the desire to from the character of Falstaff in this play as never before: in the programme this is indicated by another fold in blood read for nob great reason with an article on Sir John Falstaff by Oxford Professor, Emma Smith.

Not much in this article though helps us with the reimagination of Shakespeare’s character by McKellen and the production – for Falstaff is in the stage for much of the time even when not speaking, that also involved lifting a scene from Henry V, the last history play in which the character appears and in which he dies, and an entirely new scene, with good blank verse to boot, in which Falstaff turns his military reputation to valour into a tool for the advertisement of bottled sack. I except though the decision to feature on the page the sentence from 1 Henry IV, Act 3, Scene 3 ‘Thou seest I have more flesh than another man and therefore more frailty’. For the frailties of men are clearly to the fore in this production, particularly those leading to a desire for gain (money, power, status, lifestyle and easy accumulations of more of the above) at the expense of others Again more later.

But what of my fleshly failures as a reader of expectations. It is my wont to prepare for plays I am to see by reading the text, especially of an adaptation but here it was not possible, for it is not yet published (no doubt because its true run is later in the spring in the West End of London and what I saw was one of the touring preview performances). Nevertheless, I prepared myself by re-reading the two Henry IV plays and blogging on those, looking for innovative openings. It was of use to me and what I wrote is available at this link in full, though I will quote its views where necessary below. but I wasn’t figuring with as innovative a redesign and direction as I could have expected from Robert Icke and Hildegard Bechter had I known their past work better, including an Oresteia, Hamlet. Mary Stuart and Oedipus, not of which I have seen or read Icke’s adaptation of the original plays.

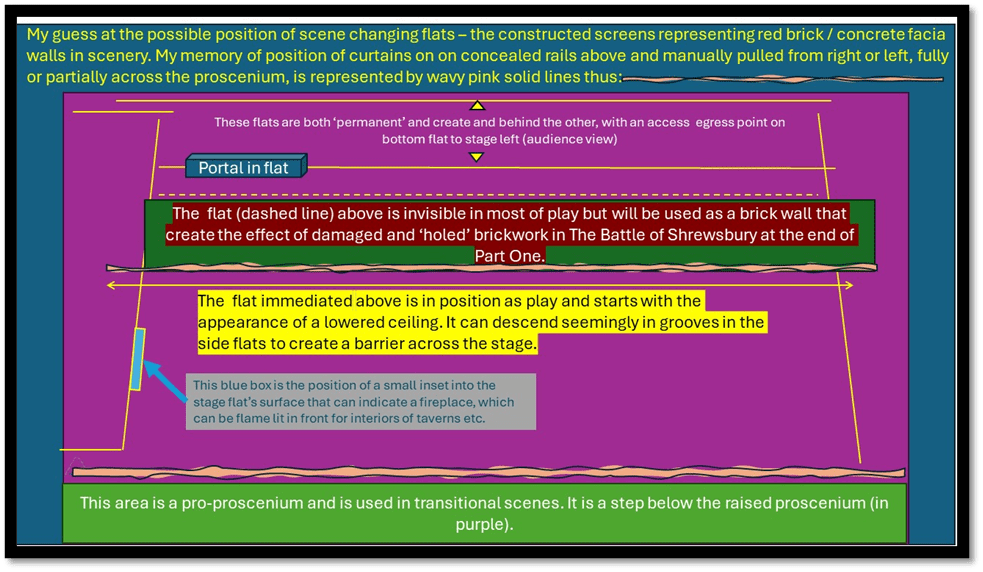

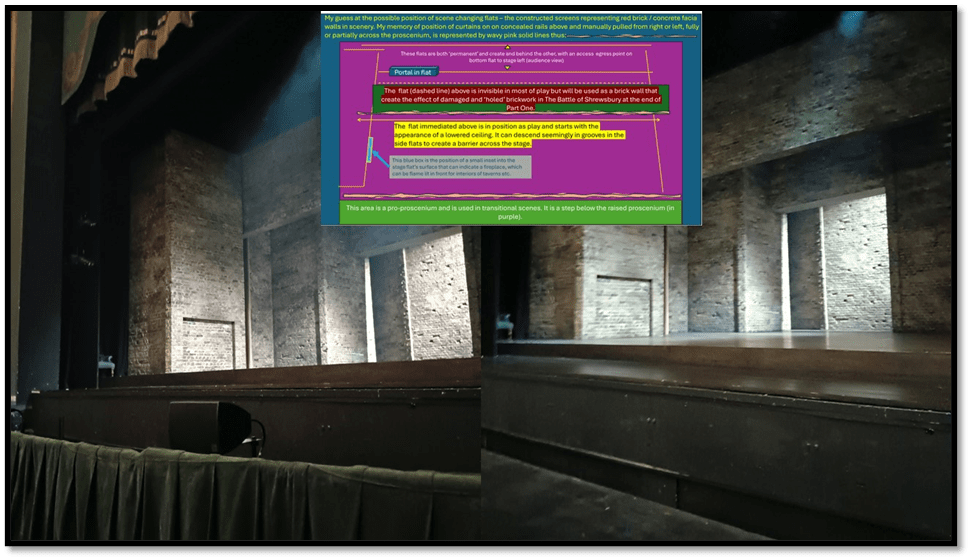

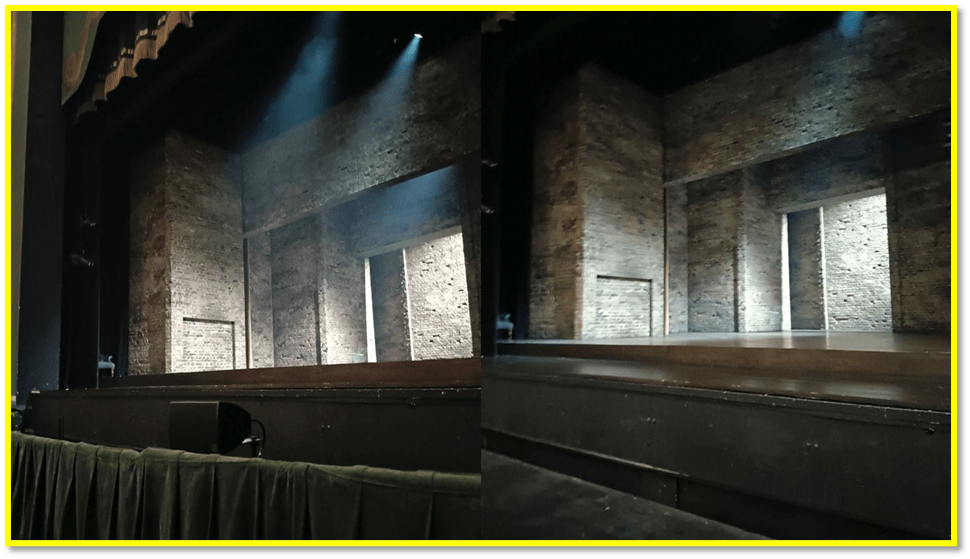

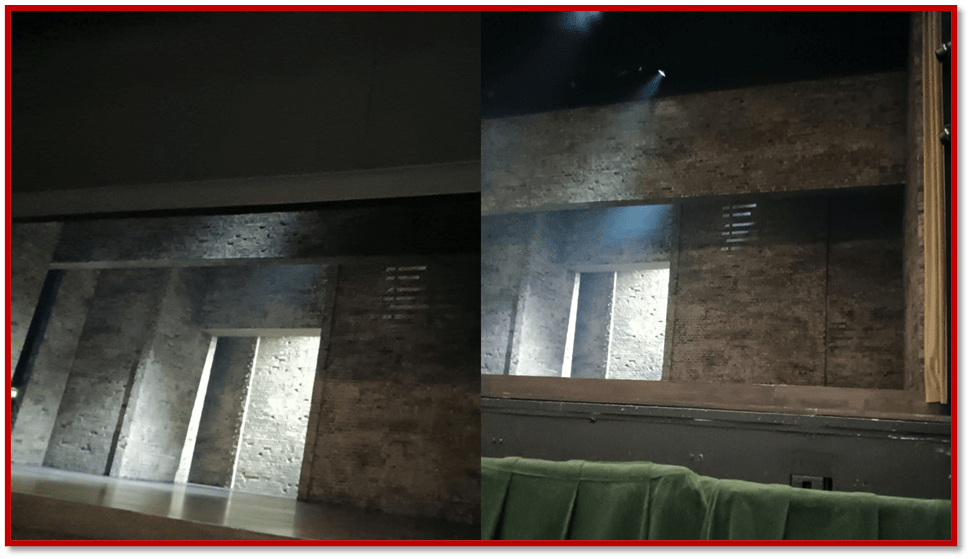

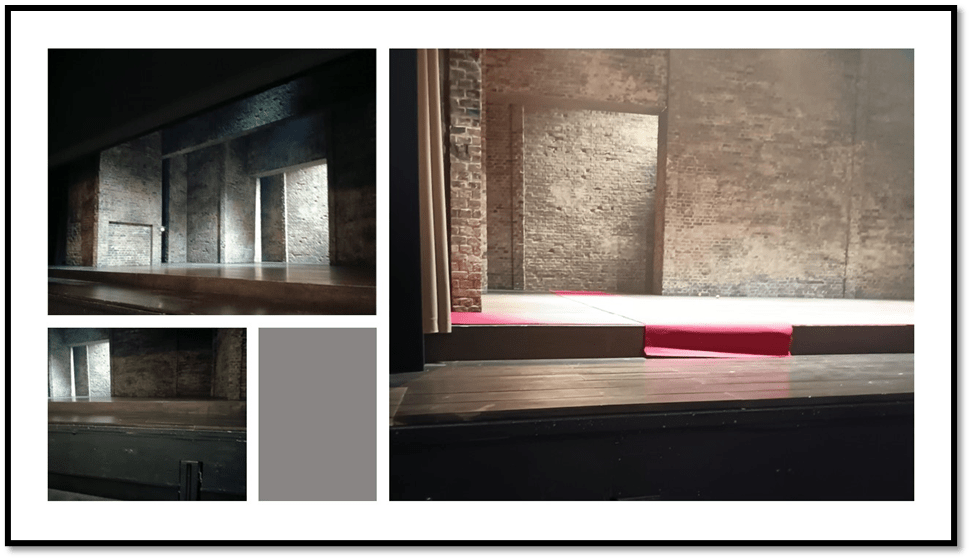

Let’s start with the design of the space on the proscenium stage. This was open to view from the start and what follows are some attempts to capture the stage and its affordances, which, based on memory of one performance alone, is likely to contain errors.

The photographs I took of the stage space are mainly from the before the house lights are turned down but showing the distributions of both lateral and vertical space, given that this too modified by flats that descended, one showing in the picture becomes a blank faux ‘brick wall’ facia. Other flats had portals like the basic access/egress point shown in the basic structure. These had a kind of urban feel to them, especially in basic light with no colouration cast on them. They reminded me of the entry to alleys or blind areas in a mass of concrete housing, the surface effects were of concrete and brick asserting the modernity of the scene especially in the scenes not in the Royal court.

Other flats were modified to show the effect of a bomb shattering holes in the structure during the reconstruction of the Battle of Shrewsbury. Beyond this, curtains were used to pull across the stage, drawn manually by the actors that obscured space partially or fully behind their line. These allowed for scene changes, relating to change of venue or time. They also soften a scene sometimes, or raise it from blankness, where the message suggested a need of luxury above the life of the visceral scenes. Below is my graphic conceptualisation of the stage, followed by its imposition on the photograph above in the hope of helping in imagination of the space created and manipulated.

Of course lighting plays its parts in transformation of space that is also transformed by costume and properties such as furnishing that have associations with the delimitation or suggestiveness of position or local. I find it useful to keep looking at the space and imagining such effects and the lateral and vertical movement of the moving flats that can be seen in the three-dimensional illusion of the photographs.

Note how lighting filters create the effect of light falling through barred windows below for instance.

The last scene represents King Henry V’s going into his coronation, occurring at the end of 2 Henry IV, where Falstaff is banished. A red carpet has been spread along the route before Henry comes in and leaves by the portal. Note how softening the light is in the photograph on the right of the collage below – the photograph was taken as I exited the theatre but recalls the stronger coloured lighting effect. However I cannot show the effect of the curtains for photographs were not allowed during the performance.

But I have been promising for some time to critique my preparation in the light of the usual practice of Icke and Bechtler, In the article on them by Rosemary Waugh in the programme’ Waugh says that Icke starts adaptions with a clear ‘”no’ list” of things he hates or “wants to kill” in a genre or its reception in theatrical history – perhaps evebn in the text of the play’ and for him these included actors’ with ‘stylised speech patters or big hand gestures’. Such stripping back goes for setting scenes too as we have seen, but another instance of change is a rather played down bawdy in some of the comedy. My reading in my preparation made something of the need to draw out a queer element in the play.

The combined used of coloured curtaining and cast light on flats and shifts in space size allowed for different space sizes and volumes to be suggested – lower ceilings outside court for instance, though battles tended to be represented as like urban and guerrilla fighting – the context of Gaza felt scarily present. The ceremonies made the stages’s variation come into their own starting with a brief coronation in full regalia of the modern Henry IV where the attributes of the king were as swift stripped as they were put on by his nobles. The coronation of Hal as Henry V made much of the relative comfort or discomfort of this young man eager for power. There was nearly always irony in the script.

These sets asserting the artifice of creation of ceremonial space were exploited in the added scene where Falstaff is lauded as a hero in a dinner party as he advertises bottled sack imprinted with insignia of his supposed valour. From behind curtains Falstaff could still rob tables of free promotional sack.

But the acting was everything, as the rehearsal shots below (from the programme) show. Here was a troupe trained to forget the eminence of some of its members. Only then can sophisticated and nuanced distinctions be made between the relative sincerity, or more importantly authenticity of the enacted personages, themselves oft acting a role, as Falstaff constantly. If I got anything right in my preparation blog it was about the means by which this play took the theme of unstable authority and roles in authority related to counterfeiting kings in battle, the use of roleplay to disguise or manipulate an image before an audience or the sheer naked hypocrisy of those in power. This production had little time for kings and their pretensions. The most sincere character was Hotspur whose direct masculinity reached almost bulging proportions in its enactment by Samuel Edward-Cook, who did the same for his second role Pistol. In each case here was a loaded gun of phallic masculinity discharging itself everywhere. though as Hotspur, he died as a result of a playactor’s trick – for playing dead is a theme of this play until people must be dead in fact. Only an acting team united by faith in the nuance of their task as a unit could have carried this off.

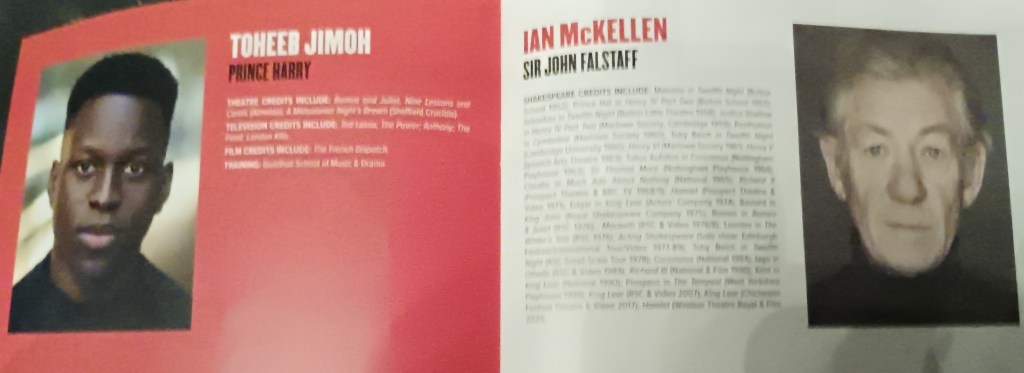

As the second scene started I thought I would get that as drag queens and whores frequented the ribald scene. In front of the guy as much as anyone the finely shaped actor Toheeb Himoh who was Prince Hal played in his underpants gyrating on a table and playing to Poins in particular. Both he and Poins then sucked cocaine from the back of a naked man (but for leather minimal underwear and straps) but the language I depended upon was stripped from the play as were other rake offensive terms that might be overly sexist or homophobic. The Pricking scenes were deleted entirely, and Justice Shallow and Silence were no longer ambiguous, as was Falstaff’s ‘Will you tell me Master Shallow, how to choose a man? Care I for the limb, the thews, the stature, bulk, and big assemblances of a man?‘ I think this done consciously. However strong the masculine stereotyping of Hotspur, his homophobic slurs were missed out of his account of the Messenger of Henry Iv’s court asking for his Scottish prisoners. There were no holiday and lady terms or talking so like a waiting-gentlewoman (1 Henry IV, Act One, Scene III, 361ff.). This was so apparent, it was difficult to know why Henry IV’s nobles should sympathise with his resistance to ‘such a man’.

Likewise though Silence’s songs remained in 2 Henry IV, Act V, Scene 3, the direction given to the actor robbed that nuance I see there. Hence when Silence sings the song below, he gives sentimental emphasis to the word ‘dear’ as if the monetary reference could not be allowed, and the meaning shifts to the notion of ‘lust lads’ yearning for dear ladies than the ‘take what you get feel of the original song set in its context of ‘pricking’.

When flesh is cheap and females dear.

And lusty lads roam here and there,

So merrily,

And ever among so merrily.

In effect the play has little or no truck with a queer theme, except in that allowance of it in a first scene of young riot. And, in a way, that is good, if no sense can be made of it and if the theme of enacting manhood is played down for more emphasis on the direct power of the state. After all in this state, Warwick (the John of Gaunt kingmaker of Richard II) is brilliantly played as a woman, who looks somewhat like Liz Truss when in role, Annett McLaughlin). Some approaches make no sense when that is done, for the insistence on the patriarchal in the play is diluted. And. of course, this has strong positive effects.

I think the stress falls instead on the notion of power as a thing that can be so performative, that it is always in danger of being seen for a sham and hence exceedingly defensive. This will explain how and why Henry IV, Hal and Falstaff are played as they are and seen in relation and analogy with each other. I hinted at this in my preparatory blog but not enough for this production that continually cuts men away from the clothes and other signs of rank they pretend are the real them. Hence the bookending of the ornate coronation scenes and its sumptuous clothing and properties of medieval kingship so at odds from the setting and the means of modern warfare shown. Icke’s adaption truncates the scene in which Hal wears the crown of his father before the latter is dead but does so in a way that even more stresses Hal’s falsity and inauthenticity – as power-hunger pretending to nobility.

One of the screens that lower on the stage bears captions and these emphasised the ‘counterfeit kings’ theme played to confuse the field at Shrewsbury. Falstaff is not so much a queer feature of a corrupt world as almost the emblem of that falseness, if done in a way we accept as ‘human’. Nevertheless his nastiness in filling pits with the dead, in order to take the excess money for pressing them for himself, is much the same as Henry’s false dealings confessed to his son at his death. indeed Falstaff falls sick and apes dying on stage to the rear of Henry, in order to force the similarity in these men.

The modernisation of warfare and fighting also lowers frighting from valor to trickery, with guns and knifes being common to the warfare of aristocrats as to the street thugs led by Falstaff, and which Icke based on characters from Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, we are told in the programme. Street gang fighting with cunning sleights with gun and knife are alien to medieval chivalric warfare but certainly so was, as Shakespeare always intended to tell us/ knife fights. The effect of killing by gun is not that of an ‘equal’ sword fight. That is how Hotspur treats Hall, only for Hal to play dead and shoots Hotspur when unguarded. Guns kill at distance and they enable shooting someone who has no defence. again the theme of the naked of power is emphasised. This is the more important when power pretends to legitimacy, as usurpers and their sons must. In this production we feel the mauvaise foi of both Henry Iv and Hal. They fail to keep agreements, effectively use deceit and are difficult to distinguish from Falstaff, except that people seem to find him fun to be with.

The general nastiness of the sovereign state seems the picture given, that resonates with its recourse to bombing its enemies and the breakdown of brick walls, that might symbolise civil society in this play. Their trick is secrecy and sleight of hand. Hence I think the walls work well in this play and emphasis that much communication in i is behind barriers and employs the darknesses and opacity that barriers and curtains help us make. In the end the focus of this play production is on the negative in the defence, and even the attack, on established power against which it sets a barely illustrated negative image of what ought to matter to human beings. It does that this production with a brooding concern with death.

Men are in it much of muchness, although Doll Tearsheet and Mistress Quickly come off well in comparison with the men they have to sexually serve. The team acting it, often by transitions when a supposedly absent character remains on state to make analogies between themselves. Henry VI is like Hall, and both are at bottom like Falstaff , just as Northumberland is a false version of the rather meat-headed Hotspur – all man and no brains.

The inclusion of Falstaff’s death scene from Henry V, in the report of Mistress Quickly (Henry V, Act 2, Scene 3, 9ff,), makes for one of the finest delivered speeches in this production:

Nay, sure, he’s not in hell: he’s in Arthur’s bosom, if ever man went to Arthur’s bosom. A’ made a finer end and went away an it had been any christom child; a’ parted even just between twelve and one, even at the turning o’ the tide: for after I saw him fumble with the sheets and play with flowers and smile upon his fingers’ ends, I knew there was but one way; for his nose was as sharp as a pen, and a’ babbled of green fields. ‘How now, sir John!’ quoth I ‘what, man! be o’ good cheer.’ So a’ cried out ‘God, God, God!’ three or four times. Now I, to comfort him, bid him a’ should not think of God; I hoped there was no need to trouble himself with any such thoughts yet. So a’ bade me lay more clothes on his feet: I put my hand into the bed and felt them, and they were as cold as any stone; then I felt to his knees, and they were as cold as any stone, and so upward and upward, and all was as cold as any stone.

As full of textual; errors as we know this speech to be, it is beautiful whether by Shakespeare or not. But its import is to contrast stone to flesh, the stuff of statues in one’s supposed honour and renown and the living flesh. Delivered as they were in this production they made the point that Falstaff like other men dies but that he dies in the care of people who love him rather than use him and manipulating him. He was a man who used and manipulated and in truth has no respect for his friends just reliance on them. But what he had was worth more: love directed at him – something no other character has. Emma Smith in the programme article sees Falstaff as timeless and perhaps he is, although I find that word usually empty of effective meaning. I have some sympathy with this sentence of hers: ‘ Appropriately, he represents more than he is: his size becomes less a description of a weighty man and something more all-encompassing’. And that happens despite his flaws and perhaps because his moral frailty is made akin with the frailty of heavy and tired flesh. We are all flesh. We all die. How much fuss we make to use ourselves to puff up pride.

To create a Falstaff of such giant proportions, you need a great actor skilled in drawing out an ensemble. At last I feel I have seen Ian McKellen as he should be seen.

Do see this play. It still hymns to itself in my heart and brain

Love

Steven xxxxxxx