‘It occurs to me that good songs may haunt the mind not despite their incompleteness, but because of it’.[1] This blog pays homage for providing a book that, despite my expectations will stick with me for a long time. This blog is about Kazuo Ishiguro (2024) The Summer We Crossed Europe In The Rain: Lyrics for Stacey Kent London, Faber & Faber.

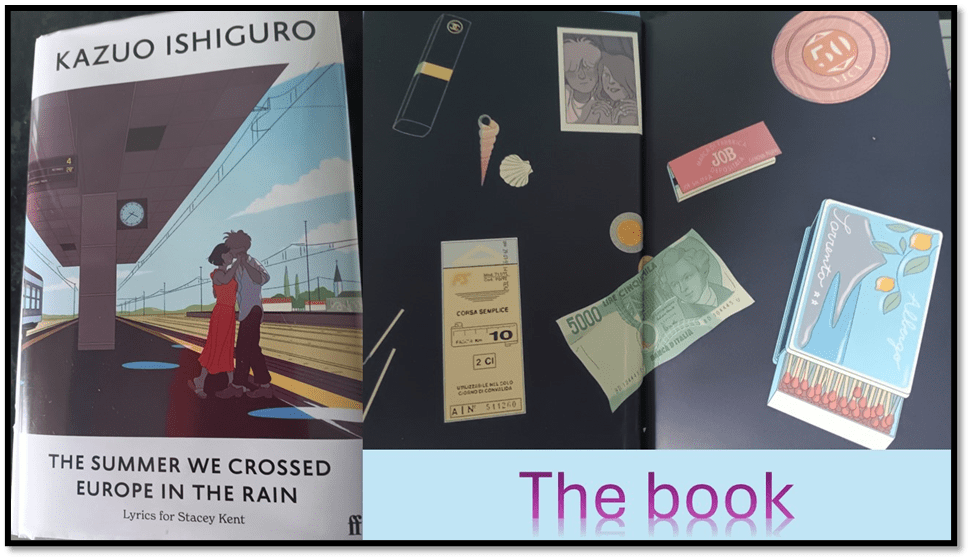

It all seems very unlikely to me: that I should buy a set of lyrics written precisely for a jazz/folk singer called Stacey Kent and in collaboration with her husband and colleague, musician, Jim Tomlinson, but I did. I have still not heard any of those lyrics sung by Stacey Kent, though some already exist and have won awards – but the truth is I am unmusical and need some kind of great push to expose myself to something I fear because I so often fail to understand it or even find its satisfactions . Nevertheless, having read these lyrics they will stay with and in their endurance – for reasons I will tell you later – they may grow into the experience of the music, at least I hope so. This point about endurance matters to Ishiguro because he addresses it in his ‘Introduction’:

A song lives or dies by its ability to infiltrate the listener’s emotions and memory, like a parasite, take up long term residence, ready to come to the fore in moments of joy, grief, exhilaration, heartbreak. No one aspires to write a song that catches the attention only while it’s being heard, then gets forgotten. That’s not how songs work.[2]

I have to say I recognise that descriptions of how some song lyrics, and songs with their music integrated in the moment, stay with me, or come back when they are suggested by title, trenchant or subtle quotation, or snatch of sound. And I have to say these lyrics (by which word I mean entirely herein the ‘words for a song in their formal printing and delineation like poetry) do that for me. It is likely that will lead to facing Stacey Kent and Jim Tomlinson as an integral part of that experience sometime. No matter, these songs are capable, even in the partial form of the printed word, will live in me. And here I think I disagree with some artists who talk about lyrics as an unliving fragment of the experience of song, as virtually the experience of song deprived of what is a large part of its animation. According to Dorian Lynskey, Jarvis Cocker put it thus: “seeing a lyric in print is like watching the TV with the sound turned down: you’re only getting half the story”.[3] While Lynskey says that Ishiguro agrees I think Ishiguro’s pronouncements in his Introduction to this volume are much more nuanced. They are even more obviously nuanced, because essentially less playful, than Simon Armitage’s words on the matter, who has a thing or two to say about the distinction between poetry and song lyric (see my blog at this link for a further consideration of Armitage’s views).

When Ishiguro says that his printed song lyrics are ‘incomplete’, he does not do so in a statement that claims reading them is a partial experience that is necessarily less than the experience of the song as performed in one of many potential variations of performance. I know he would agree with Lynskey, as would Armitage, saying:

While they can certainly be literary, a lyric is just one channel for conveying meaning in a song. The vocal delivery, melody, rhythm, arrangement and production are all used to enhance, or sometimes subvert, what the words are saying.[4]

But then so do differential readings of a poem ‘subvert’ what we think a writer, their narrative persona in a poem, or their characters are saying. It is implicit in the debate about detection of irony in literature, as well as polysemic interpretation. And Ishiguro rather likes song and, as he implies, novels too which wear an incomplete aura that turns people off novels like The Unconsoled, about a musician in fantasy out-of-time Europe too, as Lynskey recognises also, and quoting Ishiguro at more length will bring me back to my title quotation.

I’ve often wondered, …, if there isn’t something in the unresolved, incomplete quality of so many well-loved songs that’s significant here. In the world of prose fiction, there’s a strong impulse to achieve completeness; to tie every knot, answer every question, to leave no loose ends hanging. By contrast, in the world of songs, there’s a much lower bar when it comes to literal sense-making…. / It occurs to me that good songs may haunt the mind not despite their incompleteness, but because of it’.[5]

Whether correct or not, and Ishiguro is tongue-in-cheek here with regard to his rather numinous prose fiction even when he is at his clearest about narrative coherence. It is his way always to leave ‘loose ends hanging’. But his songs in this volume have this quality as both narratives and evocation of mood and memory – they revel in their incompleteness, as all informed views of the operation of memory as a mental operation co-involved with imagination must. You cannot read his wondrous novels without that understanding growing upon you, if you truly read them. Most of his novels are about created, wilful or unconscious gaps made in narrative memory, and cut into us for that very reason. Apparently Stacey Kent told him she admired this novels but wanted their incompleteness to be somewhat more hopeful, at least by a ‘tiny sliver’ of hope than his novels that were ‘pretty sad’.[6]

Dorian Lynskey is pretty informative about the response Ishiguro possibly hope to create in his lyrics in The Summer We Crossed Europe in the Rain. He says:

These lyrics can still be read as extremely short stories. He took the image of the tram ride in Breakfast on the Morning Tram from 1995’s The Unconsoled, the novel of his that most resembles music because it prioritises mood over meaning – or rather, the mood is the meaning. It is no coincidence that the protagonist who wanders through a dream-like central European city, is a pianist. When Ishiguro writes that songs allow for “narrative vacuum and gaps; an oblique approach to the releasing of information”, he could also be describing his fiction.

These lyrics also dwell on travel and the slipperiness of human connection but they contain more hope and romance than Ishiguro’s novels. They occupy the timeless realm of jazz standards: trains and rain, old movies and exotic locales, myriad variations on the theme of love. The journey in Bullet Train becomes a metaphor for the way time slips away: “It feels like we’re not moving / Though I know we must be moving … Way too fast.” The second verse of Craigie Burn, with its deft sketch of a life derailed, performs the classic songwriting trick of leaving the listener/reader to imagine the full story.

This picture predates the tram, and is in fact in a restaurant: Kazuo Ishiguro at Bob Bob Ricard restaurant in 2015 with books that look like a railway train. Illustration: Lyndon Hayes for Observer Food Monthly available at https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/mar/15/kazuo-ishiguro-i-used-to-see-myself-as-a-musician

These metaphors of travel have been done many times They are done quite exquisitely, and with a link to the themes of social justice inevitably at the base of these mechanisms for negotiation, and sometimes commodifying, space and time in human experience, in John Berger and Anne Michael’s co-production (with integral and cognate photographs by Tereza Stehlíková) Railtracks (2012). Ishiguro, too, adds to his book with another form of art helping to complete or add nuance to his lyric narratives than the counterpoint of audible instrumental music. The added art form consists of the integral and intermixed illustrations by Bianca Bagnarelli that pick visual mood moments from a European (and elswhere – at least in the imagination for ice palaces are few in Europe) journey by lovers by varied transports including that isolated one in a tram mentioned above.

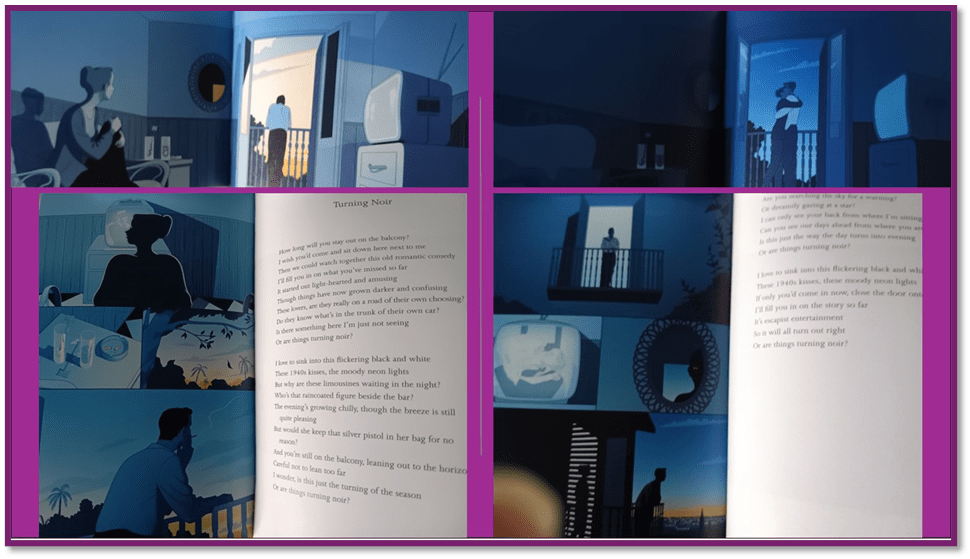

Both artists produce complentary art to each other with numerous variations in the art’s power of additional suggestiveness. I am trying as I write to recall which lyric I think works best with the graphic art illustrations. I selected first the lyric Turning Noir, which deliberately uses the ambivalence of films of the 1940s to test whether an ‘old romantic comedy’ watched on TV might hide murdered bodies in the trunk of a couple’s ‘own car’. This might be film noir (a good Barbara Stanwick femme fatale film perhaps), or it might be Now, Voyager since both types of narrative experience are evoked. The story gets lost in the gaps between different interpretations of what is happening in the story. The woman’s awareness of the tensions in the film sort of get carried into the hopes, expectations and fears she feels about thecrelationship with her nale lover across the gap between them as she watches the film with one eye and the moody lover beginning to look estranged from her as he stands on the balcony of their blue-shaded hotel room: ‘I wonder, is this the turning of the season / or are things turning noir’.[7]

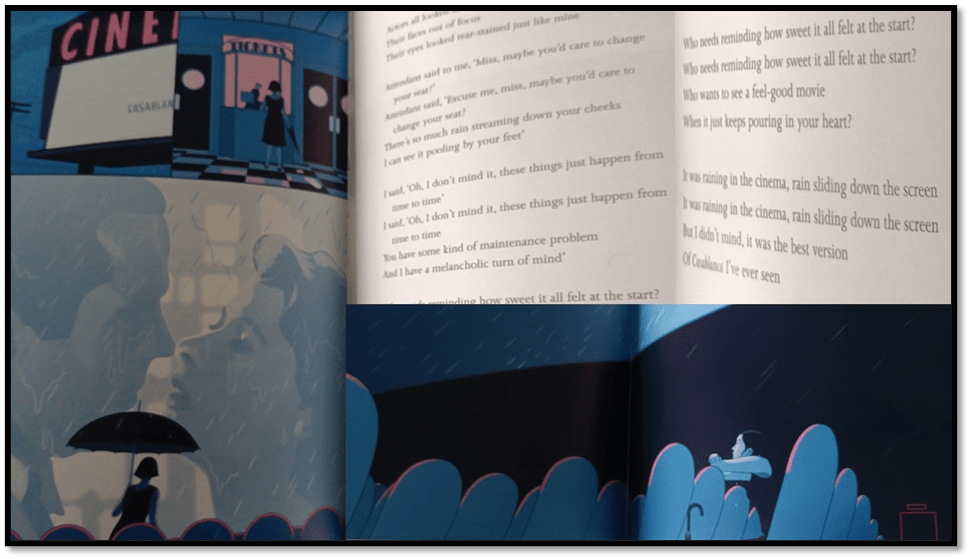

Well, that is the best example, isn’t it? No! Remember the haunting Best Casablanca where the protagonist watches Bogart in Casablanca in a cinema with so many holes in its roof that it rains in on the screen and spectators: ‘You have some maintenance problem / And I have a melancholic turn of mind’.[8]

The indecisions which pick out two competing favourite songs are part of the incompleteness of my intense recall of the lyrics and pictures left within me, and within which the memory I have of each different ‘poem’ (there I said it) pulls me in different directions, urging for its own recall rather than the recall of its competitors. Hence, I take a different track from Lynskey’s insistence that Ishiguro means it entirely when he says: ‘A song lyric is not, and works quite differently from, a poem’.[9] As in Simon Armitage’s Assembled Lyrics, you aren’t sure that even the lyric writer ever really knows the full truth – maybe because uncertainty and the incompleteness of things is always a very relative concept.

‘A song lyric … works quite differently from a poem’ … Kazuo Ishiguro. Photograph: Chris Pizzello/Invision/AP

Not being a poem does not mean, that is, that a song cannot work without music or other interaction with another artistic or craft medium. As a narrative, Ishiguro says ‘a song would not so much tell me a story as plunge me right into the midst of one, as a participant groping to find my bearings’.[10] Ishiguro is too crafty not to know that he is citing Horace’s Ars Poetica here regarding how epic poetry works:

The Roman lyric poet and satirist Horace (65–8 BC) first used the terms ab ōvō (“from the egg”) and in mediās rēs (“into the middle of things”) in his Ars Poetica (“Poetic Arts”, c. 13 BC), wherein lines 147–149 describe the ideal epic poet:[2]

Nor does he begin the Trojan War from the egg, but always he hurries to the action, and snatches the listener into the middle of things. . . .

The word “egg” reference is to the mythological origin of the Trojan War in the birth of Helen and Clytemnestra from the double egg laid by Leda following her seduction by Zeus in the guise of a swan. Compare the Iliad, which begins nine years after the start of the Trojan War, rather than at its beginning.[11]

I sense he plays with his readers here (don’t you?) who is all too ready to see poems and songs and stories as intrinsically different rather than diverse forms of communion by which a listener or reader is engaged, The narrator never knows him/herself any more than the reader in these lyrics – their motives are askew from their inner desires, their relationship to life is to its metaphors and their feelings are for its real satisfactions. They deceive us about their emotions: never crying in a cinema (about the film or what it recalls in my life) because the rain seeping in makes me look as if I am crying). I want to go travelling because it offers metaphors for dissatisfactions of which I cannot, or dare not, otherwise make myself conscious (I Wish I Could Go Travelling Again). When traffic lights change every ambivalence I feel about the series of endings and beginnings in my life are made alert and pull at each in contradiction of mood (The Changing Lights). We will find a plangent, but not bad, sorrow about the things we call Romantic when we mean sad, we will imagine our ideal holiday is in an Ice Palace, or see endings where we failed to see them at the time, get doused in rain and wonder were we happy, or wonder whether the motion of time will always defeat the things we want to endure (The Bullet Train).

This is genuinely a beautiful made book that is a joy to turn the pages of, let alone read and enjoy the graphic art. And I suspect, it will take me to the music and the performed delivery of it all in concert, but not – I pray – by being reduced to using the QR code provided on the final page.

Read, Enjoy.

With love

Steven.

[1] Kazuo Ishiguro (2024: xi) The Summer We Crossed Europe In The Rain: Lyrics for Stacey Kent London, Faber & Faber.

[2] Ibid: xf.

[3] Cited Dorian Lynskey (2024) ‘From Dylan to Ishiguro: can song lyrics ever be literature?’ in The Guardian (Sat 2 Mar 2024 11.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/02/from-dylan-to-ishiguro-can-song-lyrics-ever-be-literature?ref=upstract.com

[4] Ibid.

[5] Kazuo Ishiguro 2024 op cit: xi

[6] Ibid: xivf.

[7] Ibid: 91. Poem and illustrations are ibid: 90 – 97. The final illustration may be ironic in my view.

[8] Ibid: 57. Poem and illustrations are ibid: 55 59. The final line of the lyric is ironic in my view and is counterpointed by a wonderful final illustration.

[9] Ibid: xv

[10] Ibid: viii