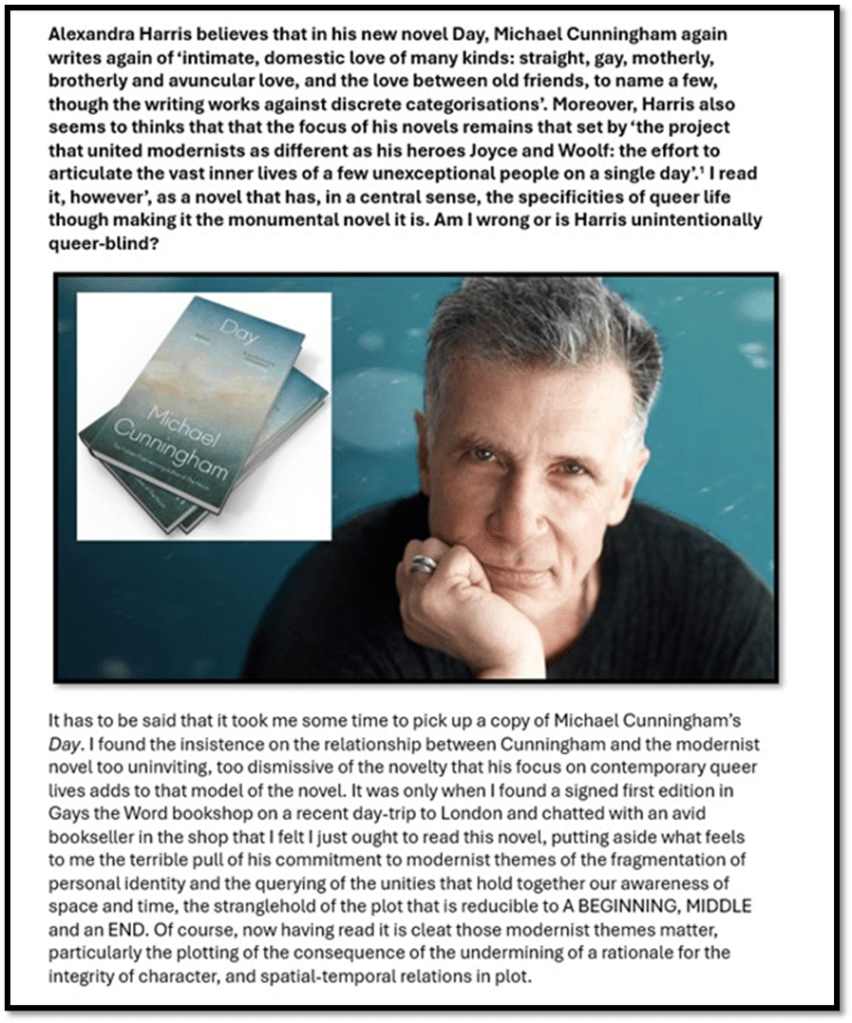

Alexandra Harris believes that in his new novel Day, Michael Cunningham writes again of ‘intimate, domestic love of many kinds: straight, gay, motherly, brotherly and avuncular love, and the love between old friends, to name a few, though the writing works against discrete categorisations’. Moreover, Harris also seems to thinks that that the focus of his novels remains that set by ‘the project that united modernists as different as his heroes Joyce and Woolf: the effort to articulate the vast inner lives of a few unexceptional people on a single day’.[1] I read it, however’, as a novel that has, in a central sense, the specificities of queer life; making it the monumental novel it is. Am I wrong or is Harris queer-blind?

It has to be said that it took me some time to pick up a copy of Michael Cunningham’s Day. I found the insistence in the critics I read on the relationship between Cunningham and the modernist novel too uninviting and too dismissive of the novelty that his focus on contemporary queer lives adds to that model of the novel. The latter is, after all, what makes his story The Years a significant one – more than just a resurrection of Woolf’s themes and persons.

Hence, it was only when I found a signed first edition in Gays the Word bookshop on a recent day-trip to London (and after chatting with an avid bookseller in the shop) that I felt I just ought to read this novel. I thought then I might be able to put aside what feels to me the terrible pull of this scholarly novelist’s commitment to modernist themes of the fragmentation of personal identity, the querying of the unities that hold together our awareness of space and time, and, consequently, the stranglehold on the plotting of novels that is reducible to A BEGINNING, MIDDLE and an END. Now, however, having read Day, it is clear that those modernist themes matter, particularly the plotting of the consequence of the undermining of a rationale for the integrity of character and spatial-temporal relations in plot. However, that is not because a novelist chooses to ape Virginia Woolf in a scholarly manner, but because these perceived interpretations of life fit the experience of lived lives that we can describe as queered.

As regards the spatial and temporal, the novel is divided into three sections, each based on one date (June 5th) in three consecutive years from 2019 to 2021, during which lockdowns were experienced during the COVID pandemic. The days evoked though are only partial days – partial in the sequence of Morning, Afternoon, and Evening. Hence, together with significant evocations of spring in spaces that shift (sometimes dramatically and in line with events, aspirations and regrets in the interactions of novel’s dramatis personae), the stage is set by this device for a significant use of symbolism to characterise the handling of time, as in Joyce and Woolf too of course.

We could take a clear example. At a moment in the oncoming evening of June 5th, 2021, after many events with beginnings and some ends, Isabel realises that in the consciousness of her boy-child, Nathan, changes are beginning to occur to him, his body and his relationships that are an ’announcement of childhood’s end’ and which spring from the effect of the biopsychosocial processes not in his control. They start for Nathan in effects of biophysical development in his body but matter, not just because they happen to him but, because these changes in him seem delayed in social comparison with their pace in his friends Chad and Harrison, whose markers of masculinity move on apace. In more than one sense the discrepancy in male development are seen then by Isabel, his mother, as dependent on ‘accidents of biology’, but, though she senses that, she cannot help him to come to terms with the feeling that: ‘Time is threatening to leave him behind’.[2] The consequences shape thence Nathan’s sense of what time offers him, robbing him of a motive and drive that had, at least for the moments in 2019, made his story significant to himself, as they do for, say, some characters in Mrs Dalloway or Ulysses when they reflect on themselves.

In the passage I refer to here, it’s difficult even to pin down where narrative and a meta-narrative of explanatory consciousness (the showing and the telling together) are located in the prose in relation to each other. Their space is somewhere in the gaps between the characters, their thoughts about their thoughts about each other and some external narrative consciousness, authoritative or otherwise (again a feature of modernist literary art). Nevertheless, there is a set of consciousnesses, including the reader’s, that shares whether, and if so how in each case, he and his mother and us understand, ‘how impossible it’s become for him to reenter the orderly passage of time’ …’.

We are told that Nathan understands the ‘passage of time’ as fragmented and discontinuous like that of Septimus in Mrs Dalloway, though in a way that is not pathologised by Cunningham as it is in Woolf’s case– a thing with large gaps in it that breaks up any sense of conventional narrative: ‘an ongoing series of minutes that arrive and depart but are not quite fully connected to each other’. But, at least these events have a serial order for Nathan if not a more meaningful one, likened to a ‘rapid-fire progression of still photographs’. [3] In that it is this, theexperience of time is at least marked at the very last as a ‘progressive’ and not a recessive or cyclical narrative like those we see in his parents and wider family, biological or otherwise. The staple narrative form of modernism being recurrent and spiralling waves, as in Woolf’s The Waves.

But to my proper budoness in this blog. In my title I cite Alexandra Harris’s view that this novel merely presents a varied world made up of the intermixture of categories of ‘intimate, domestic love’ relationship between human beings, which refuses to distinguish their singular effects, on her at least, of their discrete types. If Harris is correct about this novel, that is, it works in order not to use or distinguish in a way that matters to the novel, or its reader, the categories that normative life so often uses to clarify (or make into a discrete category – to use her term), the nature of relationships named separately as ‘straight, gay, motherly, brotherly and avuncular love, and the love between old friends, to name a few’. I think though the problem here is Harris’ problem. For me the avoidance of ‘discrete categorisation’ is already the province of writing that privileges a view of the world, because it best fits the way lives are lived as negotiations of internal and external processes, that is definitively ‘queered’.

In truth, understandings of worlds are ‘queered’ only in contrast to heteronormative classifications of the world, for most relationships – parental, avuncular, and friendship ones, for instance – are rarely easily categorised in ways that rule out other conscious and unconscious aspects (to the persons within them) of the lived relationship. That is indeed the secret of this great novel. Take its view of what constitute as a ‘road trip’, which we will do, or its handling of the complexities of the relationship between Chess and Garth, which starts as a contract for obtaining a sperm donor by Chess, who sees herself as a committed lesbian who prefers planning a life as a single mother, antagonistic to men, especially ones such as she believes Garth, the sperm donor, to be. Garth is also Dan’s brother and sibling relationships both across and within sex/gender/sexuality categories are of immense interest in this novel.

For spatial-temporal categories get queered too by the breakdown of simplistic thinking about the categories that define experience, even those in quantum physics, as the film Oppenheimer shows (see my blog at this link). Nathan’s mother, Isabel, notices category infringements after all, even in our first introduction. She sees an ‘owl’ that looks, as her consciousness in part – the other part is harder to locate – describes it, as having ‘feline’ eyes and being the size of a ‘gardening glove’, mistakable as something growing out from a tree, that looks at her, she thinks (or do we know that) as if she were as ‘utterly unhuman’ as it.[4] Moreover Robbie her brother tells her it ‘not possible’ to have owls in this area so far from Central Park and in Brooklyn.[5] Owls will flit, together with other raptors (her mother passes on to Isabel her ‘raptorish features’[6]) through the rest of the novel’s shifting times and spaces (even in Iceland and deep in the move between consciousnesses). This is, perhaps, as Isabel thinks at one point, because owls ‘symbolize some sort of misfortune’.

Moreover, she notices too categories that blend markers of sex / gender, and this links kinds of ‘queerness’ in the novel to each other, such as ‘a middle-aged man who, wearing a little black dress and combat boots, is finally returning home’.[7] That ‘’finally’ is mysterious in itself, for it is early morning and the spatial-temporal length of no consequence in the novel, though it opens up a homecoming (or nostos) narrative that claims some significance whilst being irrelevant to the novel – unlike the case of the return of Ulysses in both Homer’s The Odyssey and Joyce’s adventurer un Ulysses, Bloom. These stray moments of queerness of uncertain significance proliferate. Isabel and Robbie, her brother, discuss making their shared imaginary character created for social media and attracting Likes and followers, Wolfe, dress ‘more gender-ishly’, Robbie reminds her of how to generalise the world queerly (as she remembers him cross-dressing as a child), like RuPaul: “you’re born naked, and all the rest of it is drag”.[8]

There are ‘volleys of gay-speak’ that ‘are strictly private’ (they exclude Isabel) between her husband and Robbie, that recall a ‘road-trip’ between the men just after Dan married Isabel and which are reflected again on an ambiguous ‘road trip’ Robbie imagines Wolfe taking to Canada.[9] In this ‘gay-speak’ the men play with their knowledge of each other’s sexual preferences as if related to knowledge of sex with each other – that Robbie, for instance,’ likes it rough’. Both Isabel and Dan are aware that each prefers Robbie to their spouse, but shy from identifying sexual event in that liking – though Isabel in 2020 becomes even jealous of the imaginary ‘Wolfe-man’ once Robbie takes (as it were) the latter to his isolated hut high in the mountains of Iceland. Whilst Robbie is in Iceland Isabel writes to Robbie: ‘The world of heterosexual is a sick and boring life’. It is a lesson she wants to teach to Nathan, her son, she says because she ‘kind of hopes Nathan is gay’ – though perhaps uncertain whether Chad and Harrison are not too rough to be part of that wish, for she and Dan distrust their class-marked masculinist behaviours.[10]

I find Chad and Harrison an interesting absence in the novel, as in various ways does the outsider to their rough unconscious social homosocial bromance, Nathan. Nathan always feels cut off from them – and even Robbie does not consider any avuncular relationship with him to be lasting, as he does with her sister, Violet (perhaps because both have an appalling suppressed love of yellow frocks). Nathan is not seen meeting them by the reader but rather during lockdown we see his yearning to be with and LIKE them, even down to the smell of each other’s ‘pits’, for Nathan has given up bathing, to Violet’s disgust, in lockdown. In the scene in which, it is hinted that Nathan later thinks he let COVID into the closed sanctuary of his home threatening the life of both Violet and Dan, though all the windows were shut on Violet’s demand, in the form of his ‘droogies’, there is certainly a lot of close body contact implied between the boys, if I read the urban language well enough. Gummys can be a reference to a boy laying his penis over the eyes and head of another boy, whilst each play ‘stoner’ with cannabis and or glue (another kind of ‘gummy’): ‘Harrison bring the gummys if you still have any stoner pig that you r but come over again OK im getting too used to my own stink so bring ur BO I swear ill smell ur pits like theyre roses ’ [11]

The reading of ‘Gummys’ is long shot in this reading but the whole communication relies on the kind of double entendre in which boys excel, inviting disgust at each other’s grossness in invoking what they think impossible to imagine doing. It is like Dan and Robbie’s talk of liking it ‘rough’. The idea of fitting in often invokes shots that play with inviting an ‘outsider’ identity: it is part of the play in this novel with the interior and exteriors of room, houses and cabins, closure and openness – it is the novel’s intense and central queerness and invitation to the uncanny, including the double and likeness (doppelgänger) games played between siblings. The most pertinent novel to background such games is the one that Robbie is reading in Iceland at his death from COVID, as he awaits the arrival of his fantasy double, Wolfe: it is of course George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss.[12] It is the book the siblings Isabel and Robbie romance that the fantastical Wolfe’s intended fantasy lover (‘A single, gay farmer’ and a ‘regular-looking guy’ to avoid the hint of Tom of Finland porn) should be reading. It is a charged moment. Both recreate a fantasy love-match where they’re ‘both attracted to each other’ around the reading of a book that fails to drown with its protagonists, siblings Maggie and Tom Tulliver, their unconsciously incestuous passion which literally floods the book.[13]

Siblings are at the centre of the treatment of queer (or non-normative) sexual attraction. The book not only circles around Isabel and Robbie but complicates it by siblings-in-law like Dan and Robbie, the children of Dan and Isabel, Violet and Nathan, whose relationship is turbulent like marriage, and Robbie’s complex avuncular attractions between himself and Nathan and Violet. Sex-and-gender fall into this mix regularly to confuse it and mould its types (in terms of endurance for instance). The relationship of brothers Dan and Garth is complicated by Chess, who has rejected normative marriage, she thinks. Indeed when she teaches Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth she condemns is failure to find real choices in women’s lives, its ‘anti-Semitism and misogyny’ and a precursor of the refusal of modernism (she cites Mrs Dalloway) to put a marriage plot at the centre of the narrative structure of the novel, an idea about which her feminist students are more hopeful than she. Yet what she doesn’t say is how persistently family ties recreate the ‘marriage narrative’:

You might be shocked someday to learn how hard it is to dismantle the marriage narrative. you have no idea, not yet, how persistent that motherfucker can be.[14]

Wherever anyone turns in this novel and however far they move or run away from it, as Chess tries to move to California, heteronormativity, of which the marriage narrative is the ideological institution per se, returns in some form or other – Chess’ admixture, given the needs of her baby son Odin for some dependence on the marriage plots structuring the life of Robbie, and through this queer friend to Isabel and Dan with whom he lives, and thence to Dan’s brother, Garth, who becomes Chess’s sperm-donor but wants more. Does Chess the confirmed lesbian? Who knows by the end of the novel for if it doesn’t evacuate the conventional marriage plot ending, it cannot eradicate the marriage plot potentials.

In Day, is difficult to even structure single-sex attachments around expectations that sound like marriage, as Chess finds, but Robbie too – although he connects to marriages at one or more queer removes, though the Maggie to his Tom, Isabel, through the expectations of fidelity that keep emerging in the fantasy of Wolfe – first the gay farmer, then the elopement with Robbie to Iceland. Sex fantasies displace real foundations for relationship in playacting, as for the Irish maids who once lived in the same attic room now inhabited by Robbie in his sister’s apartment, who escaped marriage narratives in Ireland, with the famine, only to find themselves a virgin in an attic, a housemaid with poor expectations in life. And Robbie is not unlike them, or Wolfe, who are both ‘cheerfully virginal, for all the beds he’s been in and out of’. [15]

Think of the beautiful stories of Robbie’s ‘exes’: Zach (the college boy trial), Peter (in whose relationship both learned sex-role versatility through ‘bottomification’, Adam – the best romantic beginning of all yet but who dropped him for a fellow musician more LIKE him, and the most hopeless of all, Oliver. All get represented, except Oliver for there is ‘nothing here that Oliver did touch’, now ‘gone, without a trace’.[16] He dies dreaming Wolfe is coming home to him.[17]

In the end stories of attachments are stories of likes and that word (especially in the form ‘Likes’ to recall the device of momentary attachments on social media). Like can extend to mean attachment to but it also portends identifications (of looks or souls as in double stories – and hence can spark competition between those too alike) or even the word body in it its origins. This novel utilises all of those meanings at various times, and is brilliant in showing, that the culture of LIKES in social media is based on them – they are a kind of magical thinking that can identify where there is no genuine identity, embody feeling where there is no feeling (or body other than in emoji icons) . Wolfe, for instance is what They (his Followers) Like, which is a set of stereotyped accomplishments but written up if as perfection: ‘They Like that he lives in Brooklyn with his roommate, Lyla, and with Arlette, their recently adopted beagle-and-whatever mix’. He is the fantasy of the ordinary that sees itself as just as ‘being itself’ and therefore special, unreal enough to be what ought to be, if ‘Wolfe were real’, ‘the elusive figure at the heart of the story’. He lives in the recesses of fairy tale that animate all the characters, from when they were children but not just as children, but all those adults who, as they slumber on awaiting a kiss, are Sleeping Beauty:

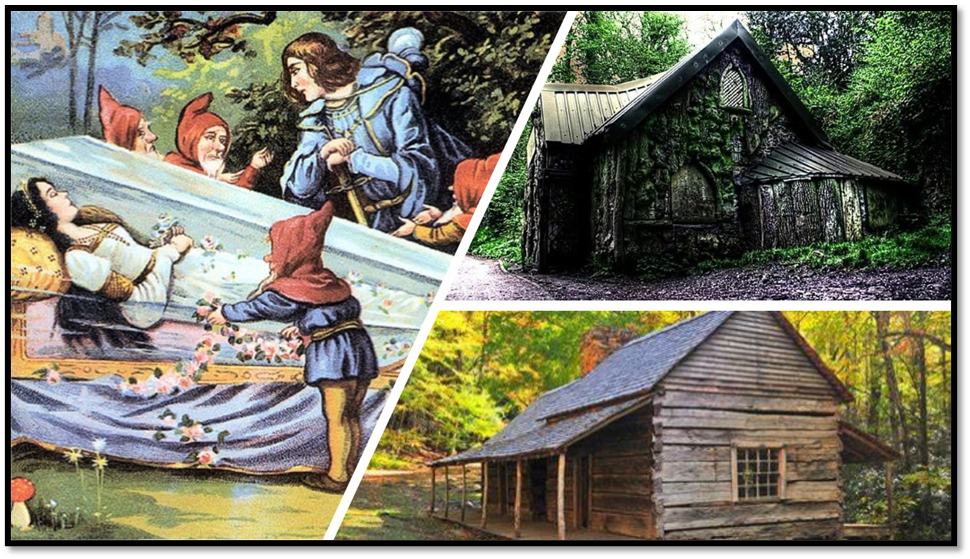

He’d be the animated, friends-encircled guy you fail to meet at a party, the athletic-looking stranger glimpsed as he strides off the B train, the prince whose kiss might fix everything if he were able to find you, comatose in your glass casket, deep in the woods.[18]

Fairy tales are a motif of this novels – they exist at the level of the desires and fears of the characters – desires that can be murderous in their pursuit of happy endings. Their symbolic motif, in terms of the cusp between realistic story and those desires and fears, they are in the symphony played in this novel on the theme of houses in or near woods, protective enclosed walls that make an inside for you and dangerous places outside. The story in 2021 is set in a house, one like that Isabel and Dan wish they could ave moved to earlier, so that Robbie might not have had to leave them. It’s a place gifted to Isabel and Robbie’s imaginations by Ms. Manley, the 5th grade teacher with ‘a romantic relationship to reality’ that is in fact totally impractical , as Robbie says the ‘next-nearest gay person’ would be at least thirty miles away.[19] Robbie Googles such house to imaginatively gift to Wolfe to inhabit with his fantasy farmer.[20] Robbie even searches in his dying letter to Isabel for an unlikely ur-myth, ‘a fable about the house vs, the woods, and they’re both dangerous’.[21]

In the 2021 section of the novel, Isabel has separated from Dan and is living in an unsafe haunted house in an unsafe wood with a more unsafe lake. The house is one where the ghost of Robbie taps on violet’s window at her invitation though she does not let him in. Shadows enfold house and trees from the outset, for it is evening.[22] Later Garth sees it as ‘moldy (sic.) and dank’, the house and its surroundings an ‘endless swathe of pine forest. …, claustrophobic (it offers no horizon, only infinities of trees)….[23] From this danger, he rescues Nathan from the consequences of his near suicide in the lake. Emerging from it Nathan thinks of it as a fairy tale wood ‘where wolves or demons or candy houses awaited the children who ventured there’. Nathan sees himself as changed in this experienced just as Hansel and Gretel are, by facing the fact that survival of death is a sufficient step into another story and the ending of one tending to bad, as Robbie’s did .It is enough to start time going again for him perhaps:

They emerged unharmed. Nathan wonders now if the stories failed to mention how the children had been changed. Who wouldn’t be, if they’d shoved an old woman into her oven, or outsmarted a gnome who wanted to eat them or been pulled by a woodsman from the belly of a wolf.[24]

These motifs of the enchanted uncanny – of fear and desire (wolves and candy houses, eating sweets or being eater) are dangers in woods and houses and in the cusp between them. And we should note that for Nathan, as I see it, is the likelihood that he would like Robbie become the young queer man who failed like Robbie to escape the tragedy of Liking and being like Wolfe (for he has teeth too and absorbs you) rather than carving a new life. It is THE queer dilemma.

Together with the motif I mention at some length above is another one – the poor responses that we make to both feat and desire. Afraid to effectively keep it out (of which one strategy is Violet’s desire to have all windows closed whatever the reason) but which rightly refuses the ghost of Robbie egress so that she and he find separate routes in life as Nathan and he should. Nathan himself attempts half-conscious suicide in a cold lake because he thinks people blame him for letting COVID in 2020, possibly by leaving doors unlocked for Chad and Harrison, and that that blame and his own guilt will entrap him. It takes his survival to change him as we have seen – but with no promises of a better future than his muddling older family, for there are no such assurances.

And I think. As we finish, the novel we realise that queered lives – in which COVID is an element in the queering by the fears and desires it raises – to stay in or to go out – has returned us to the need to distort the well-structured narrative of beginning, middle and end, just as the Modernists did. This novel is about people contemplating large changes.

- Choosing to Move out: From Robbie’s ultimatum from his sister and Dan to move out of their house, to moving out of prescripted plans for living like his parent’s wish for him to enter medical school, to which he sends Wolfe in fantasy instead. From stultifying marriages or stultifying isolation. From childhood or other life stages. Robbie’s life-moves become frantic until he finally moves out of his country, eventually to Iceland, and then yet again out of a lived life entirely.

- Choosing to move in: to a new home or a new or renewed relationship, as Robbie tries to move in again into Violet’s part of his long-desired house in the country, the resumption of a marriage or the beginning of a trial one with new freedoms.

- Choosing, as Eliot does so many times cyclically in The Four Quartets to make a beginning of an end or an end of a beginning. In Wolfe’s ‘signing off’ note (now written only by Isabel) that ends the novel. In both cases it is about the acceptance of queered time where patterns of time inherited from the past are not enough to enable us to survive life in its passing:

It’s the end of This and the beginning of That. Thank you for wanting to know. … Here’s there’s something I can only call immaculate, some state of sacred suspension, but soon it’ll be time to come home again, and go on from there. It’s almost time now.[25]

This resolution of queerness sounds like the same one that modernists found for the fragmentation of meaning caused by the philosophical and practical meaning of the great old ideas_ the soul, the nation, the family and so on. It fragments in order to sealed in a new ‘sacred suspension’ of time, till we live it again as we must. And, though I do not wish to pursue it further, this resolution is for Cunningham in the same thing – art that aspires beyond the temporal dimension. Even if we do not believe in transcendence, the pursuit of it goes on. In this novel, it survives even in the poor art of Dan, and that is sustained in the songs and singing that are metaphors throughout the novel and not just in Dan’s attempts at finding meaning. And they are in photographs and our understanding of their curation (Isabel’s work and Wolfe’s too though these photographs are stolen by Robbie to give to Wolf’s thin substance), Chess’ teaching and Garth’s sculptural art with its reflection on Shakespeare plays. There is more to say here, but not by me.

Would love any chat with anyone interested. Do read this novel It genuinely sings. Try this, for instance, which I cite from an earlier blog (read full blog and my comments on the passage at this link). In the passage below, Isabel communes with Brahms’ Requiem as if with time itself: past, present, and future. The music remains in the prose:

She is free to conceive a celebration of mortality itself, death as a beginning as well as an end, the cracking open of a glory that defies description but, when it reveals itself, may not be the cherubim and seraphim of the official glory Isabel was asked to aspire to as a girl, the painted clouds and winged child on the walls of our Lady of Fatima. This is glory of another sort, a depthless luminous darkness or the wheel of a galaxy or a fire that cleanses as it burns everything away. [26]

So goodbye for now. Comment if you wish – even more so if you want to discuss further.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

First draft on Twitter

[1] Alexandra Harris (2024) ‘Day by Michael Cunningham review – living through the pandemic’ in The Guardian (Thu 25 Jan 2024 07.30 GMT) Available in: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/jan/25/day-by-michael-cunningham-review-living-through-the-pandemic

[2] Michael Cunningham (2024: 203) Day London, 4th Estate.

[3] Ibid: 210

[4] Ibid: 1 – 3.

[5] Ibid: 16

[6] Ibid: 13

[7] Ibid: 1

[8] Ibid: 39

[9] Ibid: 25, 22 respectively

[10] Ibid: 127ffHer and Dan’s dislike of those lumpen boys ap[pears elsewhere.

[11] Ibid: 148

[12] Ibid: 217

[13] Ibid:40f.

[14] Ibid: 86

[15] Ibid:9

[16] For these exes, see 60 (Adam), 88ff (Zach), 91 (Peter), 94 (Oliver) & 99ff (cycling back to Adam again). Adam refuses to be in serial order anyway – for that ‘marriage of true minds’ has to keep asserting itself.

[17] Ibid: 198

[18] Ibid: 7f.

[19] Ibid: 17

[20] Ibid: 47

[21] Ibid: 195

[22] Ibid: 201

[23] Ibid: 248

[24] Ibid: 259

[25] Ibid: 269. The last words of novel are at the end of this quotation.

[26] ibid: 154