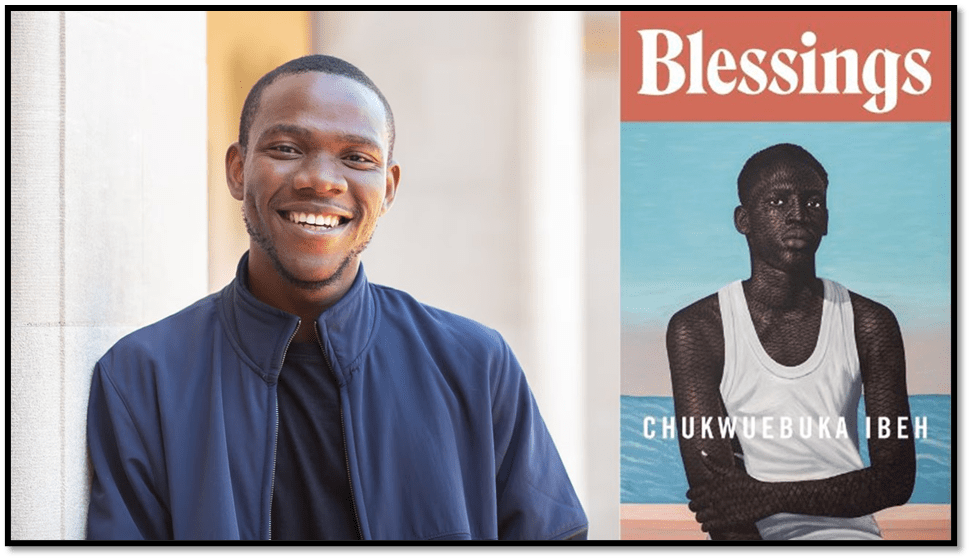

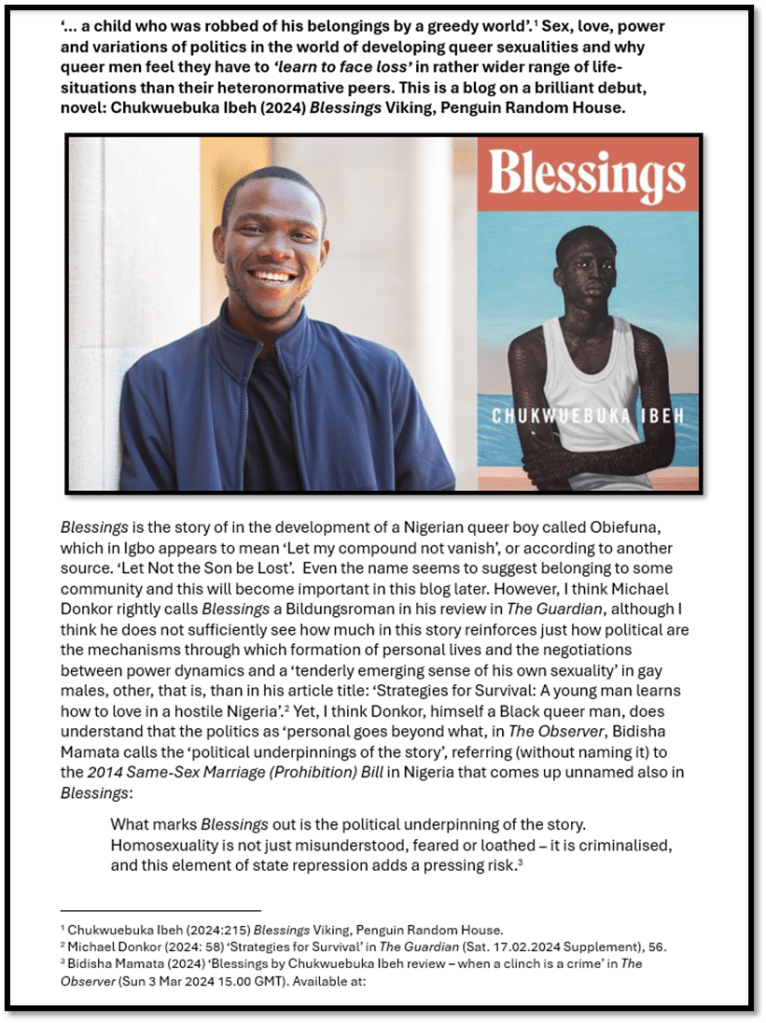

‘… a child who was robbed of his belongings by a greedy world’.[1] Sex, love, power and variations of politics in the world of developing queer sexualities and why queer men feel they have to ‘learn to face loss’ in a rather wider range of life-situations than their heteronormative peers. This is a blog on a brilliant debut, novel: Chukwuebuka Ibeh (2024) Blessings Viking, Penguin Random House.

Since Blessings is the story of the development of a Nigerian queer boy called Obiefuna, Michael Donkor rightly describes the novel as a Bildungsroman in his review in The Guardian. Yet, just because a story tells of personal development does not mean that it is not a deep analytic reflection of the mechanisms through which formation of personal lives occur. In particular, it is a form that ought to help us understand in what ways the personal is political over and beyond mere identity politics, though of course those subjective chosen identities play a part in it. What I mean about going beyond ‘mere identity politics’ is that it is not enough to tell the story of a ‘tenderly emerging sense of his own sexuality’ in a queer boy and man. Indeed, I think this phrase of Donkor’s misleading for queerness is not an emergence in the novels main character but a manipulation of the meaning of his queerness or ‘specialness’. And Donkor, himself a Black queer man, does understand that politics is in the personal, although it shows mainly in his article title: ‘Strategies for Survival: A young man learns how to love in a hostile Nigeria’.[2]

However, this concentration on a negative story about the fate of LGBTQI+ rights in Nigeria is not enough either, in as much as it speaks ONLY of Nigeria. Forming a ‘sense of our own sexuality’ occurs unevenly in the modern global world for people who identify within the range of LGBTQI+ potentials, and not only in Nigeria. Indeed, Western commentators sometimes demonise African and Caribbean countries in ways that ignore the unsavoury parts of the story of becoming a queer person in the world in every country of it including the supposedly ‘liberated’ West and North. This is a point argued by brilliant writers such as Kei Miller in the Caribbean (see the blog at this link), as well as in the flowering of the contemporary pantheon of Nigerian queer writers and allies. In truth queer identities are everywhere and every time a negotiation that occurs within a network of power dynamics that pull and tug at the self from many directions, the most empowered of which are those of the hegemonic heteronormative in terms of sex/gender and sexuality, tender or otherwise, emergent or enduring and relatively stable.

However Donkor is a step ahead of The Observer’s Bidisha Mamata who picks out what she calls the ‘political underpinnings of the story’, referring (without naming it) to the 2014 Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill in Nigeria that comes up unnamed also in Blessings:

What marks Blessings out is the political underpinning of the story. Homosexuality is not just misunderstood, feared or loathed – it is criminalised, and this element of state repression adds a pressing risk.[3]

And this point, true as it is of the final sections of the novel and events in it, is not quite adequate of the range of subjection of the personal to the political in the novel of which consideration of anti-queer law is raised as we shall, I hope, see. After all, the state is not everywhere and in everything that leads to damaged queer lives (even if we believe, as I do that family and education can act as ‘ideological state apparatuses’ as Louis Althusser called them). In effect, we need to see how unevenly distributed power in communities, institutions, cultures, nations and global phenomena shapes the nature of things we call ‘abstractions’ like love or empathy. No queer man raised in the shadow of a wider but unevenly practiced heteronormativity could miss this fact for it gets to the heart of a necessary tangle with one’s very being and relationships. It is this interaction between sex, love, power dynamics and politics (both at micro and macro levels) that I want to look at in this blog, whilst, as always (for me), worrying out the relationships between the personal and political that I think fundamental to understand, especially for queer men or people who identify as LGBTQI+.

It may be that as readers in English we can, if we do not work t it miss the cultural fineness and nuance of Nigerian writing, so strong as it is currently. For instance the boy whose adulthood we see develop here is called Obiefuna, which in Igbo appears to mean ‘Let my compound not vanish’, or according to another source, ‘Let Not the Son be Lost’. Even the name seems to suggest belonging to some community and this will become important in this blog later, where the places and peoples to which I belong and which confirm my sense of having belongings become extremely important. For instance, when Miebi, a man to whom Obiefuna has a relationship, that seems to him like a marriage , decides that with anti-gay laws tightening and the atmosphere becoming more toxic for ‘out’ gay men, decides to choose a heterosexual marriage, Obiefuna is told that their relationship must end or become a secreted affair. To be thus ‘freed’ by Miebi, as Miebi sees it, does not leave Obiefuna in a good place as a single man without a home of his own or community of friends surrounding it, some of the queer members of which like the feist Edward have also opted for sham heterosexual marriage.

One of those friends, Patricia, offers (although the idea came from Miebi) to link Obiefuna to a man with the power to do this who is willing ‘to help facilitate an asylum application for you if you need it’. This is one of the fissures in the only sustaining ‘out’ queer community Obiefuna has ever experienced and it reminds him of the fate of another member of it, Tunde, who has taken asylum from them and Nigeria, a double loss of communion, after being victimised by cult gangs. Obiefuna’s response to Patricia is quick, but is not, I think final:

“I can’t,” Obiefuna said. He thought of Tunde, smuggled out of the country under the cover of night, disorientated for weeks on end, leaving behind all he had, all he knew. “Everything I have is here,” he said.[4]

Migration is an extreme instance of the severance of communities even when it is prompted by state oppression. It is an extreme example of the reshaping, reforming or rebuilding of personal lives that illustrates the violence with which self and its experience is determined by being, as it were, thrown into such determinations demands that one see oneself in a prescribed way, or approximating to it. At the very least, when such ruptures occur mid-life the effect is to force one to see oneself differently from before, especially in relation to the sense in which you belong or have belongings – in families, institutions, chosen families, communities and nations. Sometimes these issues are not related to queer identity at all. For instance when Obiefuna arrives at the seminary his slippers are ‘stolen’ His new-made fiend (it is no surprise that his name is ‘Widom’) tells him that all belongings of new boys are forfeit to those who having power in a school. Those powerful persons are named, without being identified as the ‘owners’ of property easy to purloin.[5]. Never, has the ‘property is theft’ axiom of Proudhon ever been better illustrated.

Hence the poignancy of the quotation I use in my title, that feels so much stronger in its context, which comes in Obiefuna’s memory of his lost communion with his mother in the flesh. It comes from Obiefuna’s memory of his mother, at this point having died of a cancer he for a long time was not told about. She tells a story to her child that is iconic of other losses and thefts that growing up in an environment into which you are thrown, as Heidegger explained the emergence of all being, and to which and whose influence you are inevitably exposed. The whole passage is beautiful and of a piece with how the learning of tenderness or otherwise with regard to love and loss is tied into institutions, which in the form of embodied persons, actually raises us in forms both conscious and unconscious. And there is much in the relationship and communion between mother and son that neither truly knows of the other and which they learn alone in abstract reflections that are the glory of this novel:

He thinks of his mother as a star. Sometimes, she manifests in his dreams as a small dot in the sky, the lone light that stays on even as the others fade. She doesn’t speak, as far as he can tell, but he can hear her voice singing a lullaby she used to sing for him as a child, something about comforting a child who was robbed of his belongings by a greedy world.[6]

We are all children I supposed whose ‘belongings’ (in both senses of the word) are insecure, for most worlds we know are competitively hungry and ‘greedy’– though some to an degree validated institutionally like those of patriarchal capitalism and its apparatuses.

In this novel whole harmonies are played on that word ‘belongings’. Sometimes discords connect it to an alien world that believes in its rights over you, even down to the ownership of your slippers or your affection or your very being as a Nigerian citizen, setting conditions to your right of belonging or having belongings. At other times it concords with some ideal or comforting alternative world of mutual experience never quite fulfilled except in glimpses and touches of tenderness. It is echoed in asylum extremely as I have already said and here discord is prominent: Obiefuna sees it as losing : ‘“all he had, all he knew. “Everything I have is here,” …’.

We may see this as apolitical, at least as with regard to Obiefuna’s sexual being but some of which what he ‘has’ in Nigerian culture is lost, or at one remove from his consciousness. Indeed it is fostered only in his mother during her long period of alienation from communion from him which she but only barely fights. In my reading this lost belonging of Obiefuna’s is represented by that marginal character, that we never see in the flesh but only in the retold memories of the children that Uzoamaka, and her sister, Obiageli, once were and then, devastatingly, in news of his death. The name is of this person is Achalugo. One mane-meaning site offers the meaning of this name in Igbo culture as ‘versatility, enthusiasm, agility and unconventional methods’, although another says, ‘gift of God’, and yet another, ‘shines like an eagle’. All of those possibilities mark the character as special but I think the suggestion of unconventionality also important, especially in terms of the growing together whilst remaining apart of Obiefuna and her beloved first son.

Achalugo is of non-binary sex/gender identity and the novel plays with that naming of him. Achalugo is thought of by some, for heteronormativity is widespread, in the instance of Obiageli and Uzoamaka for instance, as a man ‘that used to dress like a woman’.[7] Yet it is clear too that Achalugo was revered by his Igbo community, associated with the musical instrument, and musical style called ogene, which has religious, tribal warfare and communal celebration associations, together with accompanying ritual dances, that are also treated as communal entertainments.

‘Ogene ndi Igbo’ By Mplanetech – File:Ogene.jpg, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=90602556, See various types of ogene in play at: https://youtu.be/9RyTjNvEyvg

Although, as a young girl, Uzoamaka felt she could not dance, she has Achalugo recalled to her by her delicate son, Obiefuna’s fascination for dance, that he incorporates into semi-participatory games with his more conventionally boy-like brother, Ekene, as in this beautiful dual memory.

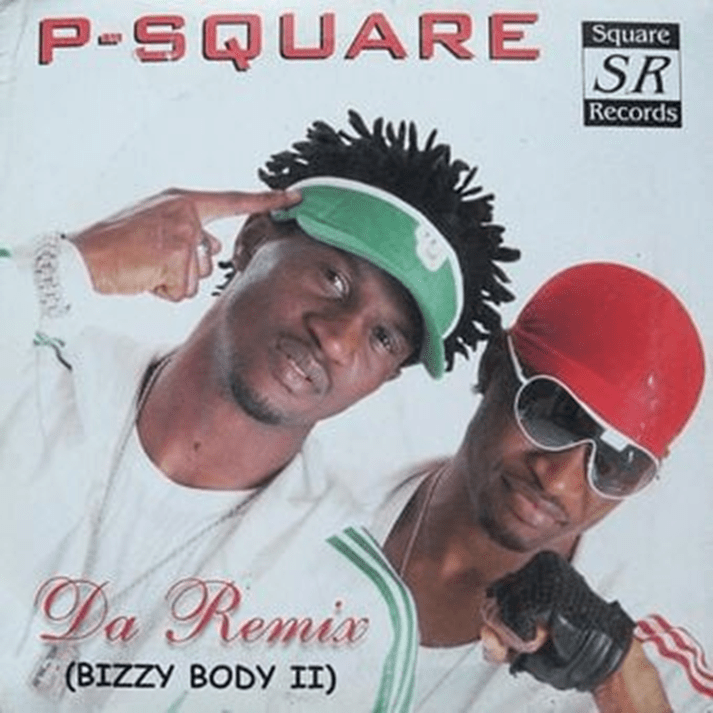

That day, she peered through the window of the living-room and suddenly, powerfully, Achalugo was brought to the fore, made stark by the sight of Obiefuna dancing, the sweat coating his bare skin as he moved from one end of the room to the other, screaming the lyrics of the song ‘Busy Body’.[8]

Somehow P-Square’s song title has been conventionalised for us as readers of English, although such moves would more or less rewrite the actual lyrics to the song referred to Bizzy Body. But the point is that P-Square (written ‘Psquare’ in the novel) is a duo of twin boys, and although the words refer to a female body, two very beautiful boys, apparelled to maximise their masculinity, gyrate together.

And for Uzoamaka, the memory we have already had recalled above on the same page is about Achalugo and their kindly and androgynous softness to a girl who had failed in the dancing in which Achalugo excelled and for which reason she was brought to tears by the cruel laughter directed at her by the other girls (community you see is never nuancedly ideal even in our memories).

What fascinates me in the writing of this is the breakdown of fixed pronominal references in the prose to describe Achalugo from some point of view it captures. That point of view is problematic. Is it Uzoamaka’s young mind recalled directly, or in the transforming memory of the incident in an older woman now faced with the challenge of a queerly identifying son. For, as she thinks of this the mother is conscious of her husband Anozie, Obiefuna’s father, punishing Obiefuna for supposed effeminacy as well as because he observed him kiss the male apprentice he brought into his house, Aboy. Retreating from the bullying girls, Uzoamaka ‘wiped her eyes’:

It took her a moment to recognize Achalugo. With his mannerisms, his beardless, heavily made-up face in the waning light, he could have passed for any other woman around.

“Why are you crying?” he asked her. He had a serious look on her face.[9]

I have to say I did not realise the ‘gender dysphoria’ here in the portions I italicise (to coin a psychiatric phrase inappropriately but it is part of the power struggle in the novel over queer identity) until my re-reading, where my original reading of the novel was beginning to develop further into its present form. It is beautifully and brilliantly done. When the character is mentioned again, it is when Uzoamaka is attempting to use his example to ask her husband, Anozie, to be more accepting of their son and to reflect on the fact that Anozie had sent ‘him away … shut him out’ (although Anozie thought he did it for Obiefuna’s ‘own good’.)[10] What Obiefuna’s mother does here is to use an acceptance of difference in Igbo pre-colonial (or as in this case extra-colonial) behaviour and belief as a culture to persuade him that Obiefuna should be brought back into the ‘compound; to ensure that the ‘son’ not be ‘let lost’ (the Igbo name of Obiefuna thus comes into its own). Without doing so fully consciously the novel here resurrects theories about ‘intermediate types’ (Edward Carpenter’s word) that are still matters of vital interest to pre-colonial history (the link is to a 2017 blog by Shanna Collins). As Obiefuna’s mother reconstructs Achalugo’s life as a ‘lost child’ or orphan:

She could not think of him without thinking of the tinkering of his ogene, the sultriness of his voice as he beckoned all to dance to his melody. No one knew for certain how he had come by his style. For as long as any of her peers could recall he had been there, just the way he was. She believed that he was an orphan, having lost both his parents in the Biafran war> she knew of one of his uncles, a wealthy businessman who had tried many times, unsuccessfully, to have him checked into a psychiatric hospital, knew that the futility of this action was largely due to the village’s intervention. They stressed he posed no danger to anyone. He lived alone in his tiny hut near the village square. When he was not performing, he was a smallish man of nondescript bearing, bore no resemblance to the larger-than-life figure that made even the most unfeeling detractor throw an unconscious foot forward in homage to the sound. He had possibly died alone in that hut, with no one at his side.[11]

The reference to Achalugo is what gives this novel its wider socio- political edge, and propels it into questions about the limits of social being imposed by politicised norms over and above modern or ancient uses of law, and gives the discussion of Nigeria’s anti-gay laws a richer and less localised (and racist) aura. And I think I want to insist on this richness in part because this debut novel has in its Acknowledgements a reference to another exceptionally fine queer Nigerian writer, Arinze Ifeakandu. In an earlier blog on Ifeakandu’s first book (of luminous short stories) I wrote as follows (use this link to see the entire blog which also references Colm Tóibín).

The title story of this collection,‘God’s Children Are Little Broken Things’ was shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2017. To write here therefore of this story collection as a collection of ‘queer love stories’ might seem to appropriate it for a concept more prized in the Global North and West than the Global Southern and East. But let us not make that mistake in understanding, though Ifeakandu himself, now a citizen of the USA, insists that there is some point in creating a queer literature that recognizes that, as he says in an interview with Ucheoma Onwutuebe that: ‘Homophobia is everywhere’. And there is more than a hint in what follows that the experience of the homophobia in Nigeria has commonalities with that remaining in the USA. Thus paradoxically queer people in Nigeria found the draconian 2014 Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill had ‘sparked a widespread conversation’, whilst, having travelled to the USA hoping for ‘the best gay life …, and freedom’ because that life is ‘protected by law’, he also found ‘a lot of people were closet in Iowa, dealing with homophobia, which manifests in many ways’.[3] Much of the power of these stories, however specific each is to the life, culture, law and culture of Nigeria, address circumstances which hide and enclose queer love and queer sex in a closet, the source of a social power to ‘hide’ their pleasures and feelings, that happens across cultures. There is genuinely no single answer to the question asked of the two young boys who find pleasure in each other’s bodies; the question being: ‘Who taught them to hide’?

The point is that as Eurocentric readers we must not confute the queer sexual-political and political issues in this novel with issues of local and national law alone, or even of local communal oppression, though both matter, extremely so for some Nigerian queer people suffer as we speak. The point is that issues of physical and psychological development in queer people are both bound up in this framework of power relations, forces and selective restrictions and permissions to act in the world. In my view though, this novel is about a different question to that I mention above: ‘Who taught them to lose their belongings in and to the world in which they must live’?

In essence in a Bildungsroman, this learning experience is captured in moments where loss occurs to a queer child that has to be learned to be accepted, just as Obiefuna has to accept the loss of his slippers, as the character, fascinatingly enough called Wisdom, underlines to him. But some losses are those specific to the experience of queer boys and involve active theft of more than slippers: of more meaningful attachments and mutual trust, for instance, such as that to Aboy which is not only lost in reality but must be unacknowledged in the world. Even Aboy’s openness to sexual experience relatively gives way for Aboy knows he must make his way in the world by making heterosexual choice of partner, which for Aboy seems anyway of equal value practically, sexually and romantically. Aboy has the most fluid form of sexual, romantic and comradely being in the whole novel.

In other cases it is the care and emotionality that might go with sexual (even Platonic distortions of sex into the sado-masochistic) types of bond between the unequal halves of hierarchical binaries we confront in the novel as versions of Hegel’s master-slave relationship – notably those of Senior and Junior in the Cristian seminary Obiefuna attends. The seminary is important to the politics of this novel. It is a place wherein Obiefuna’s body is abused (in various ways, not all sexual or directly so) by Senior pupils who take him as their ‘boy’. It starts with the sadistic projections of Senior Popilo (who wants only non-sexual service by the younger male and ‘buys’ Obiefuna symbolically at the end of their ‘relationship’ with a female prostitute that he pays for. Senior Kachi subjects him to becoming an ‘available tool’ (the tool being his mouth for Kachi will not descend to appear to like any other tool in a boy other than an orifice that demands subservient kneeling) for loveless oral sex that Kachi pretends not to like to avoid identification as queer. Finally, at school at least, there is Sparrow, whom Obiefuna, having been taught by Sparrow how to kiss deeply with tongues, effectively betrays for fear of sharing Sparrow’s punishment by expulsion for being caught and identified in a sexual act with an unidentified peer. Obiefuna’s face was hidden and he says to Sparrow: ‘”Please, don’t mention my name”. [12] These mechanisms of power, abuse, including those of ‘loyalty’ or empathy or liking (or being ‘like’), he loses community with other queer boys by virtue of both their degrees of self-suppression and his own self-interest in not being exposed or identified as queer. So it has been in most unwritten queer bildungsroman narratives.

Most certainly the worst of the means Obiefuna ‘chooses’ (with all the usual excuses that ‘he had no choice’ being operative in the background) to lose any chance of the strength of a queer community is by colluding in the queer-bashing of a boy at the seminary that he dare not befriend and who becomes Senior Kachi’s replacement ‘sucker’, the boy Festus, who is more effeminate than Obiefuna ever allows himself to appear, even transitionally and despite his father’s observations, in public. He observes the humiliation and beating of Festus by at least six boys including his own friend Jekwu ’until’ Festus ‘no longer resisted’. He leads off his gang happily identified with their masculine assertion, although he is inwardly scarred enough to return to help Festus, who once slightly recovered, rightly spits in Obiefuna’s face:

“You tell yourself you’re one of them,” Festus said. He lowered himself, his face inched so close to Obiefuna that he could smell his breath. “you call them your friends, but it could very easily have been you today, Obiefuna Ani.”[13]

The mimicry of the sensations of proximity in these words tell of the disgust that Obiefuna still feels in being more ‘like’ Festus than he is ‘like’ Jekwu, but also of his fear that his clear bromance with Jekwu has not been used to heal that friend’s homophobic psychosis, or at least start doing so.

These mechanisms in making attachments that are scarred by experience of being rejected and scorned and made to feel shame or guilt as a gay man even infects his adult relationships. His relationship with the drug taker, Patrick, is based on neither desire nor liking for that scorned and damaged individual but rather alienation from what it means anyway to be a queer man. Patrick is:

relentless in his pursuit of Obiefuna, who found himself driven to curiosity about him. It wasn’t meant to last. Just a minor fling, a way to get things off his mind’.[14]

This may be so, but one can’t help realising that Obiefuna here is far from fair to Patrick, for his reservations about Patrick are not shared with the latter who is later abandoned without explanation or closure. And even the novel loses interest in Patrick’s scars. In my view, such behaviours, become the reflection of the way in which queer men are socialised about the lack of value in their relationship choices. It is a mechanism Obiefuna will find used on him, although much more sensitively, by Miebi later when their marriage-like home is broken up so that Miebi, like his queer friend Edward, can choose heterosexual marriage to avoid the new law against queer couple, as I have already referred to.

Port Harcourt

With a girl, Sopulu, though Obiefuna uses the same ignorant means of ending the relationship, his friend Rachael teaches him how to mend any hurt in Sopulu’s feelings, which he would not have done unprompted. It is a beautiful illustration of how community can aid restore mutuality of duty in bonds even in ending them and one sorely poorly developed in queer communities as Michael Handrick testifies in a good book. Nevertheless examples exist in queer community in this book, as in life. Patricia helps Miebi and Obiefuna to break up more amicably, and it is in this context that Obiefuna is offered help with political asylum to some other nation, one friendly to queer men (or apparently so).

All of these instances relate to a culture that refuses to accept that anyone seen as ‘a fine boy like that can be a homo’ as Jekwu confides of Sparrow to Obiefuna, not knowing that Obiefuna and Sparrow were sexual partners whose mutual love was blooming. Jekwu add that this is particularly incomprehensible when Sparrow ‘can get any girl he wants’. Even the chaplain who masturbates alone in the bathroom, unsatisfied with his wife alone for sex, feels tarred as abnormal – as queer in a way Obiefuna understands when he catches the chaplain in the act.

However, if there is hope in this novel it is in the relationship between the brothers Obiefuna and Ekene, who learn to accommodate and love each other for their differences; physical, sexual and in accomplishment. It is Ekene who encourages Obiefuna to return to dancing, and to the suppressed likeness therefore to Achalugo. Their perfect harmony is like that of the ‘sonorous singing birds’ for song, dance and harmony have that symbolic function in the novel, a bringing together of tonal variations, of difference.[15] It is a difference with which the novel opens. People love Obiefuna as a ‘special child’ , when he is the only child. His given name suggests that[16]. But the birth of Ekene places the frail but ‘special child’ next to a socially preferred – in capitalist patriarchy anyway – a ‘boy’s’ boy, more attractive but less ambiguous than the Aboy who comes later. As the two grew together the favoured son seems to be fed from the share of the ill-favoured, especially in the eyes of a father, making him seem ‘abnormal’ to that father: “Are you a woman in a man’s skin?”[17]

The difference between the boys is cast into a dynamic politics of hierarchical subordination where the norm is that subsisting between other hierarchical binaries in the novel (like female subordinated to male, Junior to Senior). In this case the younger boy takes preference over the elder in the binary power of the masculine over the feminine or feminised. Where one category has assumed prescripted inferiority to the other, we can take a guess that the prescripted superior will feed of the other or be favourably fed the ‘lion’s’ portion.

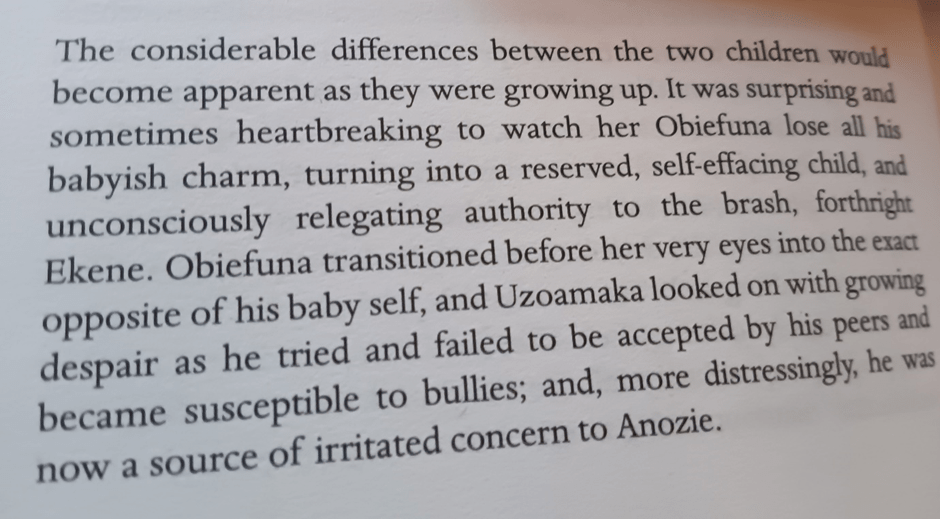

In the following passage, the surprising counter-developments in the increasing dissonance between the brothers seems to make one grow as the other reduces. It seems a partially unconscious effect of the kinds of social comparisons elicited in unjust societies where ‘masculine’ traits trump ‘feminine’ traits in men, the ‘brash’ man trumps the reserved and a rigid and hard body trumps those a boy with ‘an ability to manipulate his limbs into impossible angles’.[18] it’s the former who get the social authority of paternally modelled power divested onto it, even in school, and perhaps even in intimate couple relationships – even queer ones, for Obiefuna’s relationship to Miebi has features not unlike this. But here is the passage on the fate of differences between the boys_ differences that just magnify with time.

From page 12

This dance of authority and rigid codified power relations, so unlike the invitation to ‘all’ to dance by Achalugo, is globally a North-Western form of couple dancing that necessitates a leader and follower (even where – as dancers tell us – it is often more technically difficult to ‘follow’) not the grace let forth communally body and voice and across other boundaries to the sounds of the ogene in Igbo culture. Those Eurocentric scripted developmental relations, that look much like those described by Hegel as master-slave relationships, are the real politics of sexual lives and domestic and even communal or national organisation under colonial patriarchal capitalism and its remnants in places like the modern Nigeria. The law merely scripts them more formally and without nuance. When near the end of the novel Obiefuna and Anozie discuss the father’s earlier treatment of the boy, we get this exchange, with a fairly nice use of the word ‘interest’ as a capitalising of investment:

“Everything I did, I did in your own interest”. Anozie said. “It’s not normal to live like this. There’s even a law now against it. You could got to prison for this.”

“I’ve been imprisoned all my life, Daddy.”[19]

It is not that Nigeria, nor Port Harcourt, is like ‘Denmark’ a ‘prison’ as it is in Hamlet’s mind (bound in there as if in a ‘nutshell’). But it is a mental prison for the queer boy ‘thrown’ (in that Heideggerian manner mentioned before) into a set of social norms that imprison. The queer boy develops as in a prison by being thrown into institutions where heteronormativity, and binary hierarchy and their socio- and psychodynamic forcefields form the cages, of which the law is a wordy version. It is best to be rid of the latter no doubt – but it isn’t the real thing as it were. These circumstances instruct queer people, or cause them to learn without any contingent visibility of the teaching, that they do not belong or are inferior to those who do belong. Ans such a situation in turn questions the queer child’s rights to belongings – feeling as well as objects, self-generated ideas as well as the control of institutions. One of the grossest assertions heteronormativity makes is that there is no such thing as a queer child – only a sick child who relatives attempt to force into the psychiatric system as Achalugo’s brother tried to do to him.

In brief, I think queer people do have to learn loss in some ways that the heteronormative don’t, because otherwise they are threatened by losing the benefits of socialisation to the status quo (citizenship, working status, validation of their relationships or promotability), but I think there is a sense in which the heteronormative lose too in heteronormative hegemonic society. Cancer, for instance, occurs without warning or rationale known to us sometimes – it does in this novel whether to mothers or the fathers and sons they leave behind. But death anyway is a common end, and commonalities ought to betoken communal empathy, though they don’t always – Achalugo dies alone we think.

Heteronormativity and binary hierarchies often stop empathy short or turn it into pity or sympathy; something patronising. Uzoamaka is a wonderful character but her fears are not only for her frailer, weaker, more artistic son in a ‘greedy world’ for not only those kinds of son get lost in patriarchally violent disciplinary societies. Her fear is also for Ekene in a world ruled by brash cult male gangs even in the very streets of Port Harcourt. At one point, she dreams of being witness to the cruelly killed dead body of one of her sons, although by now she knows that she herself is dying and some of this is projection of an irrational guilt at leaving her sons behind her. But it is not the body of Obiefuna killed by a homophobic gang that she discovers when she turns the heavy male body over in her dream, though that of course is a possibility for queer-bashing is rife in Nigeria Instead it is her second son Ekene, whose brash masculinity she imagines to have taken him into the cult gangs who worship masculine values of fighting and threatening the weaker or outnumbered. There was a danger then she learns even in preferencing his toughness over Obiefuna’s gentler skills of body manipulation that she and her husband did during their childhoods. Her possibly unconscious guilt about this emerges in the metaphors of her dream: where her horror at Ekene’s discovered death (in a dream only of course) leads her to violence towards him (or the introjection of the violence that they as a family may have permitted Ekene to learn as a weapon of self-interest). To realise that she ‘clubs’ her own son while singing a ‘war chant’ is an awesome recognition for a mother:

He looks so peaceful, almost happy in death, she thinks, before she clubs at him, and screams. … “Ekene! Ekene! Ekene!” like a war chant.[20]

This is so beautiful a novel, I could write for ever. But just read it. You will love it.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

First draft on Twitter

[1] Chukwuebuka Ibeh (2024:215) Blessings Viking, Penguin Random House.

[2] Michael Donkor (2024: 58) ‘Strategies for Survival’ in The Guardian (Sat. 17.02.2024 Supplement), 56.

[3] Bidisha Mamata (2024) ‘Blessings by Chukwuebuka Ibeh review – when a clinch is a crime’ in The Observer (Sun 3 Mar 2024 15.00 GMT). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/mar/03/blessings-by-chukwuebuka-ibeh-review-when-a-clinch-is-a

[4] Chukwuebuka Ibeh (2024:241f.) Blessings Viking, Penguin Random House.

[5] Ibid: 28

[6] Ibid: 215

[7] Ibid: 126

[8] Ibid: 127

[9] My italics. Ibid: 126f.

[10] Ibid: 152

[11] Ibid: 151

[12] Ibid: 56 – 69, 91f, 104- 109. respectively

[13] Ibid: 173

[14] Ibid: 192

[15] Ibid: 137f.

[16] Ibid: 12

[17] Ibid: 13f.

[18] Ibid: 13

[19] Ibid: 245f.

[20] Ibid: 84