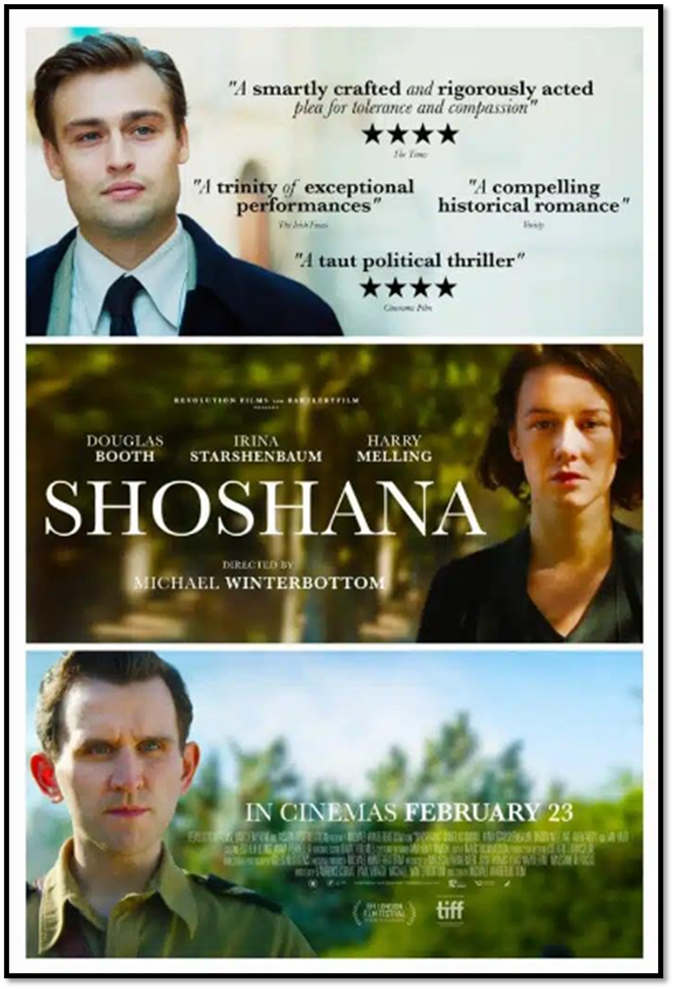

‘It is not surprising that each year Balfour Day is celebrated by the friends of Israel and mourned by Palestine’s Arabs’.[1] Does a thrilling and beautiful film like Michael Winterbottom’s Soshana (2024) help us to understand the role of British colonialism in creating the problems of the land between ‘the river (Jordan) and the sea’.

On the day my friend, Linda Goffee and I went to the Gateshead Metrocentre Odeon (Tuesday 5th March 2023 at 13.50) there were only 6 other people in the audience. Yet this is a brilliant film, both as an underplayed romance, so underplayed Peter Bradshaw with his as usual wooden response calls it ‘emotionally flavourless’, across the loyalties of communities and a thriller with pace and vitality. But it has a name doesn’t it of being over-informative and educational, at the expense it seems to be inferred of the other aims of filmic art. In The Observer, Ellen E. Jones points to the current conflict in Gaza to say: ‘Now is as good a time as any to better understand Israel, and Michael Winterbottom may be the film-maker best placed to aid us in this understanding’. That seems to promise much though it surprised me to find that in a time of a war that has brought about devastating loss of lives and capacity for maintaining them, Jones seems to find only the ‘the current media-political climate’ to define the urgency of the times. Nevertheless he is correct to say that the film has a ‘total absence of Palestinian voices’ in it. Nevertheless, what she goes on to say is also true, that:

Shoshana clearly defines its own purview, giving valuable insight into the variance of opinion within the era’s Zionist movement, while also highlighting the central role of a third player in this fraught and bloody history: British colonialism.[2]

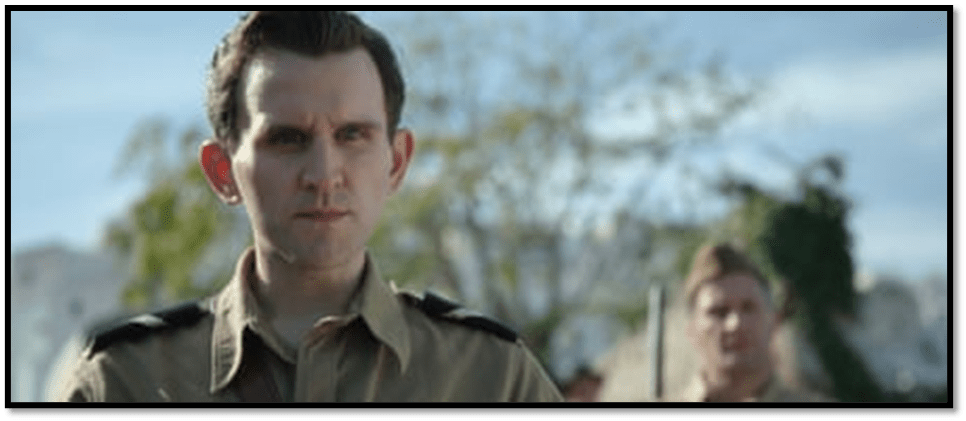

In brief, as Linda put it, this film only tells its own story and this wasn’t this time a story that focused on characters from history who were Arabs. Certainly the imperial-colonial attitude to Arab populations does emerge from the backstory of the real British colonial administrator Geoffrey Morton, played by Harry Melling, subduing Arab anti-colonialists with a vicious attitude and lies meant to play upon minds he doesn’t quite rate as worthy of respect as human beings. We see him play this through an absolute command of an imposing and stony stare, backed up, of course, with men with very big guns:

The colonial attitude … Harry Melling as Geoffrey Morton in Shoshana. Photograph: Altitude

Moreover, it is clear that the film does show Arabs as victims, perhaps more than it does the victims of Muslim terrorism, which might be a silent admission that Arab ‘terrorism’ has always been based on response to terrorist action on Arabs by the whole range of Jewish terrorist groupings before the Second World War, when Jews were a very small, if growing, through calculated immigration and settlement, organised by Zionist groupings (like that represented by Soshana’s idealist poet socialist-kibbutznik father, Dov Ber Borochov) in that minority of the population. When a ‘national Jewish homeland’ was first being spoken about widely in 1919 as a response to European antisemitism, the population of Palestine was 90% Arab. Even by 1939, despite massive programs, Jews were only 29% of the population, owning 5% of the land (though that constituted 10% of the cultivatable land). Though the film outlines a distinction between good terrorist groups, especially Haganah (meaning ‘Defence’) and bad ones, the Irgun, represented in this film, then a more extreme and anti-British-colonial movement. As Arthur James Balfour said in 1919 the British were inclined to treat Arabs as, in his words, ‘decadent, dishonest and producing little but eccentrics, influenced by the romance and silence of the desert’ (the setting for a Lawrence of Arabia indeed) against Jews thought to be ‘virile, brave, determined, intelligent’. He is quoted as also saying that: ‘I am quite unable to see why Heaven or any other Power should object to our telling the Muslim what he ought to think’.[3]

Not that Balfour was all that favourable to Jews per se, except in their quest for a homeland. Glass shows that he felt he had something in common with the openly antisemitic views of Cosima Wagner, the composer’s widow, and the ‘father of modern political Zionism, Theodor Hertzl, wrote: “ The antisemitic nations will become our allies’.[4] All of this is in the background of the attempt of British administrators as represented in the film to be even-handed, if only in consistency of repression against people who own weapons of war in both Arab and Jewish communities, which is roughly how Morton’s position is conveyed – being, as it were, just anti-terrorist, whilst befriending only the Jewish community.

Despite the ‘absence of Palestinian voices’, John Nathan in The Jewish Chronicle points out that Winterbottom has recently signed an agreement of Artists for Palestine, and hints, even in their reviews last sentence that the film as a whole is ‘anti-Israel’, if not antisemitic.

Winterbottom deserves credit for conveying complexity on a subject where fervently held opinion much prefers simplicity. Yet today’s beleaguered defenders of Israel may still view elements of the film with weary recognition of an anti-Israel stance.[5]

It seems worrying though that in reporting the truth that the distinction between Irgun and Haganah was lost after Morton’s shooting of the leader of Irgun and direct use of arms against armed and unarmed Arabs became a shared policy, the accusation of anti-Israeli views in the current moment is invoked. For this is a fact of history and Soshana Borochov’s biography, and certainly does not imply that Israel should not exist, although it does question whether the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) – the successor of Haganah – should have such hegemonic control of the State that it has.

One’s judgement of this film will depend very much on how one believes the film demands of us an attitude of identification or distance from Shoshana’s views and attitudes to the creation of Israel and the care of the Yishuv, the name pre-Israeli Jews gave themselves. Throughout Soshana is identified with the possession of guns as a means of enabling the defence of Jews against Arab forces identified by them as terrorists. She is a good shot, teaches a comrade how to load and prepare his gun and has a thoroughly articulated and subjectively very grounded feminism that shows in her every action. She is a joy to watch, and listen to, of course. He face (as communicated and played by the brilliant Irina Starshenbaum), has both emotional complexity even in its silence and totally apparent deep reflection and empathy.

However, her views are affirmatively in favour of uncontrolled immigration by Jews only, and she expresses her dismay to Thomas Wikin, played by Douglas Booth, when Britain began to control and limit numbers of European and other Jews. She is without doubt committed to an Israel that may have to be defended by guns that those of terror, as she is genuinely ant-fascist (before Avraham Stern’s killing). For the context in the late 1920s is described by Charles Glass thus:

The Zionists established self-governing – and separate – institutions to prepare the Yishuv for independence. However, when Churchill proposed representative government for all the people of Palestine, Weizmann opposed him because Jews were a minority. Similarly, the Zionists rejected “free immigration” into Palestine out of fear that Arabs would move there. When they demanded special treatment for themselves vis-à-vis non-Zionist Jews and Arabs, Britain gave it. Churchill told Weizmann that he knew the Zionists were smuggling arms into Palestine but would not interfere to uphold the law.[6]

This is the context of Shoshana’s relationship with the administrator Thomas Wilkin too, who clearly sees Haganah guns as good guns, provided he doesn’t have to admit his knowledge of them to himself, and Irgun (and Arab) ones as bad. It is this very distinction Morton rejected. Yet Soshana knows that were Wilkin forced to recognise her full views of the world she inhabits, their relationship would become the impossibility it soon becomes anyway after Stern’s death. As Linda said to me, Wilkin’s shooting of Stern was a convenient way to end a relationship whose messy and painful end was inevitable.

Now Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian does see some indirect political teaching going on in this film, that is in truth more about the perfidy of British colonial rule and the ignorance and brutality of native cultures that went with it, as Fanon too described it (see my earlier blog at this link). He says:

It is a film that speaks in a complex way to the current Gaza debate, contending that Zionism has anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism in its 20th-century manifestation: a rage against the British masters. But the implication is that it learned habits of ruthlessness from these very people.[7]

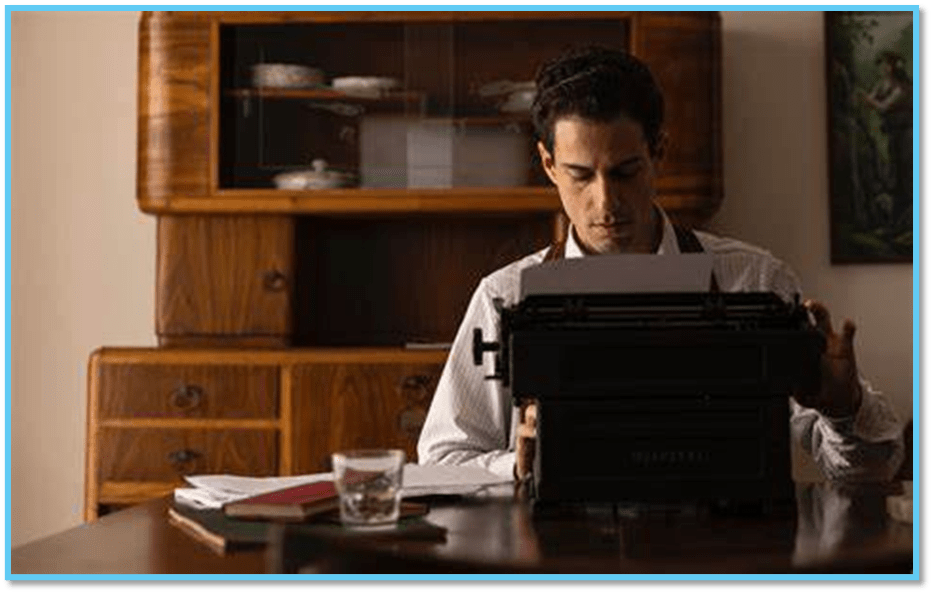

Bradshaw says ‘complex’ here but that doesn’t quite fit with him calling the film’s love narrative a ‘Romeo-and-Juliet love story’ played so under the surface of passion and dynamism that ensures ‘the political irony of their relationship is submerged also’.[8] I found the relationship both very believable and moving, though rather dependent on the drop-dead good looks of both participants. Wilkins even handles a gun in a more manly way than Morton (see below).

And, of course Stern is played as a villain with neither care nor feeling for civilian Arabs and Moslems – in whose garb he dresses for his worst acts of terror against civilians, carrying a bomb in a milk churn to the centre of a market. And he is as cool and bloodless when seen as a writer and ideologue as a participant in terror. And of course the film tells us that Stern is now a national hero, with the house in which Morton shot him turned into a museum, in Israel, though everyone in the film on the Haganah side of the Zionist project before his killing identifies him as a Fascist.’

What we inevitably learn is that the vicious beatings and water-boarding used in the interrogation of prisoners, including Irgun ones, was a British invention, though oft condemned as an American Imperialist invention. We learn too that British policy in Palestine has much to do with the particularly vicious way in which the area was left in conflict that could have no peaceful end. The resolution called a two-stare solution was first propounded by the UN in 1947 but it is clear that, although the British had promised an Arab state as well as a Jewish state as early as 1941, as Peter Shambrook finally argues in a way hard to contradict, Balfour himself interpreted those promises (to both Jews and Arab state-builders) leading to the conclusion that:

So far as Palestine is concerned, the Powers have made no statement od fact that was not admittedly wrong, and no declaration of policy which, at least in the letter, they have not always intended to violate.[9]

Sambrook later agrees with the administrator Hugh Foot, the latter himself a District Commissioner in Nablus and Galilee at the time, that the British committed the ‘double sin’ of ‘raising false hopes with the Arabs and with the Jews’ and because of the ‘fundamental dishonesty of our original double-dealing we had made disaster certain’.[10] And, although by just listening to contemporary reports on the BBC that deal with the roots of the conflict you would find it hard to believe Glass has summed up the view of modern historians (in 2001 at least) thus:

For Israel’s new historians, among them Segev and Naomi Shepherd, the Zionist project is part of the saga of white settlement, as in north America and Rhodesia. The settlers declared independence only when they no longer required the mother country’s soldiers to subdue the natives. Presenting Israelis as colonisers, rather than as enemies of imperialism, was once the preserve of Palestinian and Marxist writers.

British policy involved arming and training the IDF and eventually was, under cover of a more even-handed policy, an agent in making an Israeli state that might lead to the extinction of the Palestine they inherited, and that had laws that discriminated against non-Jews in the ownership of settlement land and immigration. Even the Balfour declaration had insisted th on the duty of safeguarding the political and economic freedom of the Arabs, which later administrators still insisted upon. Had this happened, Sharif Hussein believed at the time, there ‘would have been no Arab opposition, and indeed Arab welcome, to a humanitarian and judicious settlement of Jews in Palestine’.[11] British responsibility here therefore lies heavily on the present.

Whatever our political learning and the effect on our leaning as interpreters of history and of international and humanitarian politics, John Nathan of The Jewish Chronicle, like Winterbottom too, dismisses the criticism that there are too few Palestinian voices in the film, But he points out that, for him, the way Palestinian victims if not voices are represented is biased in comparison to Yishuv victims:

Michael Winterbottom

Nathan starts his point by quoting the director:

“It’s not about being even handed,” says Winterbottom when we meet online ahead of Shoshana’s release. “[Film] is not like current affairs or news,” he continues. “It seems to me it is legitimate to make a film about the families of children in Gaza just as it is to make a film about Shoshana Borochov in Tel Aviv. Some people have said ‘Why are there no Palestinians in Shoshana?’ But this is a story about Tom Wilkin and Shoshana Borochov in Tel Aviv. The idea we should include Palestinians is bizarre.”

Except Palestinians are included. They are seen most graphically as the victims of Jewish Irgun terrorism, with limbs blown off by bombs, writhing in agony. Towards the end of the film the bombing of the King David Hotel also figures. By contrast the massacre of “more than 60 Jews” in Hebron by Arabs in 1929 is skated over. Described as “horrible” it is not depicted in any detail except for some grainy newsreel of coffins.

So you might argue that a purportedly neutral film “about political violence” as Winterbottom describes his latest movie, should at least be even-handed when it comes to depicting victims of violence.[12]

I find Nathan’s a disturbing view of the responsibilities of art. Equality in the manifestation of violence to victims is a strange concept and anyway is not used here appropriately since showing victims in The King David Hotel was not justified by the limits of a story that never elsewhere considered the genesis of terrorist violence by Arabs, as it does from Irgun. Moreover, Nathan’s argument seems to mirror the means by which the current Gazan genocide is justified by an established state with sophisticated weapons of mass destruction against a people held under conditions of siege. There is no hiding that there was violence on both sides throughout the history of the creation of Israel, but we are perilously near the argument that one appalling terrorist crime require states to return vastly magnified violence in return, such as we see in Gaza now. I worry when this cycle of retaliatory violence will, if ever, stop and reach for the lovely novel Apeirogon (see my blog on it at this link).

My own experience of that the film is that it illuminates but requires one to read further and to understand more. And then further again … It never stops! Meanwhile human tragedies continue on both sides as the reflex of the use of violence – but currently MASSIVELY, and it seems unstoppably, in Gaza.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Charles Glass (2001) ‘The Mandate years: colonialism and the creation of Israel’, originally from the London Review of Books: One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs under the British Mandate by Tom Segev, translated by Haim Watzman. Little, Brown, 612 pp & Ploughing Sand: British Rule in Palestine 1917-48 by Naomi Shepherd.John Murray, 290 pp. Review article republished in The Guardian (Thu 31 May 2001 13.48 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2001/may/31/londonreviewofbooks

[2] Ellen E Jones (2024) ‘Shoshana review – Michael Winterbottom’s compelling romantic thriller set in 30s Palestine’ in The Observer (Sun 25 Feb 2024 15.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/feb/25/shoshana-review-michael-winterbottom-compelling-romantic-thriller-1930s-tel-aviv

[3] All cited Peter Shambrook (2023: 95) Policy of Deceit: Britain and Palestine, 1914 – 1939 London, Oneworld Academic.

[4] Charles Glass (2001) ‘The Mandate years: colonialism and the creation of Israel’, originally from the London Review of Books: One Palestine, Complete: Jews and Arabs under the British Mandate by Tom Segev, translated by Haim Watzman. Little, Brown, 612 pp & Ploughing Sand: British Rule in Palestine 1917-48 by Naomi Shepherd.John Murray, 290 pp. Review article republished in The Guardian (Thu 31 May 2001 13.48 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2001/may/31/londonreviewofbooks

[5] John Nathan (2023) ‘Shoshana: ‘It’s not even-handed when it comes to depicting Jewish victims of violence’ in The Jewish Chronicle (FEBRUARY 22, 2024 15:33) available at: https://www.thejc.com/life-and-culture/film/shoshana-review-its-not-even-handed-when-it-comes-to-depicting-jewish-victims-of-violence-iqf3gwxc

[6] Charles Glass, op.cit.

[7] Peter Bradshaw (2024) ‘Shoshana review – a quiet love story entangled in deadly Middle East politics’ in The Guardian (Wed 21 Feb 2024 11.00 GMT)n Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/feb/21/shoshana-review-michael-winterbottom

[8] Ibid.

[9] Cited Peter Sambrook op.cit: 99

[10] Ibid: 240

[11] Cited ibid: 274

[12] John Nathan, op.cit.