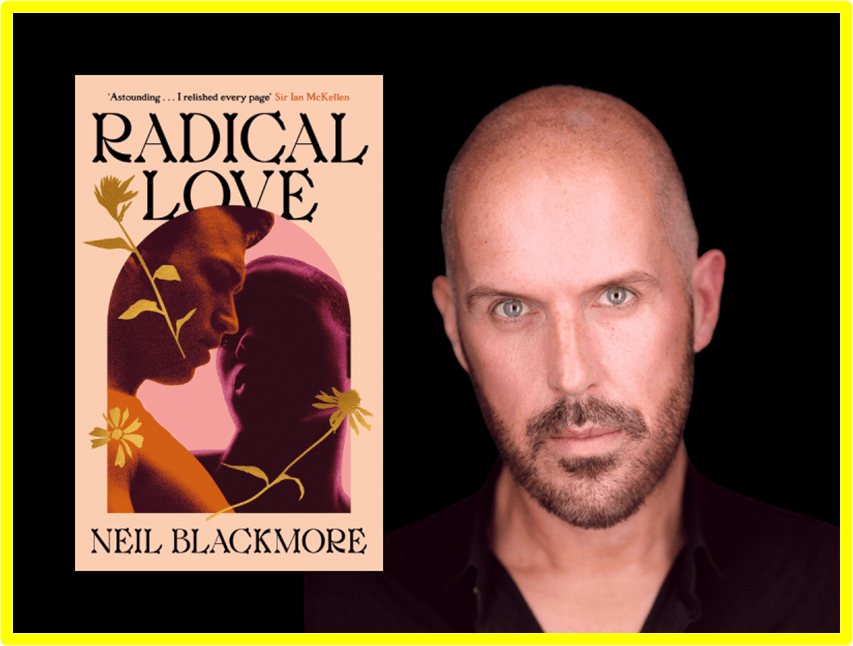

‘History is all omissions and distortions of the truth’.[1] Would there be any point in writing a novel using evidence of facts from queer history, if the truth was easily sifted from the lies? This is a very brief blog on Neil Blackmore (2023: 272) Radical Love London, Hutchinson.

This blog is just a speculation about a book I finished yesterday just to try to stave off the pain of the wisdom tooth cut from my jaw yesterday. It is a book I loved because it puzzled me. It seems to be a way of inserting the unspoken potential of a defence of queer love with the history of radical causes from the late eighteenth century, focused particularly on survival of the mores of slavery after its supposed abolition. Radicals come in for a poor press, especially the bourgeois and bluestockings of Hampstead. Wilberforce and his aristocratic clan too are exposed as hypocrites who speak radically but never act so – the black people invited to his parties are required to sit behind a curtain.

But even the feminist black radical, Lydia, has a fierce inability to understand any cause other than that which concerns herself (though she expresses distrust of White radicalism in a manner not unlike Frantz Fanon) – and acts ferociously and with a foul mouth to win her back her beautiful young lover to her arms away from the ‘hero’ of the book, the Reverend Church – a particular kind of ultra masculine and well-hung vicar with a belief, or so he claims, in universal love, although only in sex where he is ‘on top’. The only beautiful people in this book are the ‘mollies’, queer men who experiment with sex / gender roles – some preferring to be trans women, others non-binary and so on. And these beautiful people are grossly betrayed. The scene of the hanging of Tommy White is appallingly visceral. Reverend Church institutes two kinds of marriage for men in the Vere Street ‘molly house’{ sham marriages preceding a passing one-night stand, or more genuine ones in which the participants believe.

It is he who says history is lies and in telling his story, he constantly omits facts that are tantamount to lies – the worst omission is admitted in the end. And he does all this to assert he is a ‘good man’, though he often does by street fights where he draws blood, even from a man he says he loves more than any other and radically. There is no clear delineation of good or bad, truth and fiction here – nor strangely enough sometimes radicalism or extremely reactionary vengeance. I think this is why the novel resuscitates themes that feel so modern but are, in fact as old as they claim to be – such as issues of transitional sex / gender, flexibility or rigidity in sexual role-play and intersections with race, class, parental legitimacy and status – including a bully snapshot of the Duke of Cumberland who likes only black men.

Every man he ‘loves’ throughout his history turns on Reverend Church and the trial scenes are tremendous. Some minor characters who you think will be full of moral turpitude turn out not to be, such as Church’s wife, if not his father-in-law, The bakers, the Gees are like ‘white dumplings’ and pretend to kindness only to turn nasty along racist, homophobic and sexist lines.

Id you want a ‘good read’, you can’t beat this. If my head didn’t thump so, I would argue further that this book is an ethical one – one that denies easy or stereotyped virtues in its queer characters, but finds ones that shine like gold, not least amongst its drag characters. And the point of it all – queer history is built on suppressed truths. We don’t do it a justice by simplifying those truths or inventing lies about yourself to suit the story we want to tell.

All my love

Steve xxxxxxx

[1] Neil Blackmore (2023: 272) Radical Love London, Hutchinson