I am very much a person who continually questions their past, present, and decisions about the future in the light of those otherwise unconsidered trifles (thank you, Autolycus) picked up out of books. I say picked up out, merely I suppose to reference the character from The Winter’s Tale but actually these trifles seem to select themselves:[1] to jump from the page, become all serious in their intentions and whisper inwardly to me as if they bore a message. Of course, extreme versions of such phenomena bear labels that render them psychological or psychotic symptoms. Community Psychiatric teams oft held ‘referencing’, the belief that a medium such as the TV is addressing one directly, to be a prime facie indication of psychosis of one kind or another.

But I think such phenomena are as much things cut loose from beliefs about what is normative behaviour, and hence labelled ‘queer’ (a label I accept because of its clarity of acceptance of the things dubbed ‘abnormal’ or ‘marginal’). Queer things or people are queer because their perception or they themselves form are products of the reflective and reflexive functionality of complex brains (and interactions with bodies made perceptually complex in the process): those where cortical activity is often maximised (as in most primates including humans), and which we increasingly believe neuroscience to tell us are full of such mirroring functions, even the function of distorting mirrors.

This blog is stimulated by a turn to the past that a recent book occasioned. For in the past I have tried and tried, even with an existentialist – his label – counsellor, to heal myself from feelings of unexplained abandonment and rejection by another in the last year or so: a person I will call Declan. I reflected on narcissism as a cause (the blog is at this link), until a wise voice (it was a book by Matt Colquhoun (see the blog at this link)) showed me that narcissism is a nuanced arena that I needed to rethink. Matt’s book helped me to understand that we should avoid using narcissism as an explanation for anything, especially to negatively criticise or explicate another in a way that sheds a bad light upon them.

I am preparing now a blog on the novel Change by Édouard Louis. It tells of a life of change, transformation, and metamorphosis, becoming one thing instead of being another. The other other self gets left behind and labeled ‘old or in Tennyson terms ‘Portions and parcels of the dreadful past’: hence the import of Louis’ debut novel The End of Eddy. In the French title, Eddy is a fuller name and there is more active agency implied in how ‘Eddy’ is ended: En Finir avec Eddy Bellegueule. What is left behind is a working class family name and a diminutive nickname of a first name, what is adopted is a bourgeois name, the one, with its other linguistic and naming resources fully appropriated,in which persona he writes; Édouard Louis. More of that in the blog to come. Here I want just to focus on a referencing passage. Here it is in the French:

Est-ce qu’en changeant je voulais faire comprendre aux autres que je n’étais plus comme eux, est-ce que j’avais compris que changer ne voulait pas seulement dire devenir quelqu’un d’autre, mais aussi ne plus être comme d’autres, et donc repousser ces autres, les abandonner, les mettre désespérément au-dessous de soi ?

Wanting to be like another person or set of persons, in brief, means abandoning and rejecting others who sustained the person one once was, for whatever duration and it does not only have to be the ‘long duration’, to invoke the French phrase. In the structure of the book as an auto-fiction Louis’s persona narrates the story by imagining an audience of one each time he takes the next progressive step away from the self-image he leaves behind to be a representative dramatis persona from his last life, the old and abandoned one. The metamorphosis that occurs is of self (called eventually Édouard Louis) but each self one becomes must include new others to the sustain that new self. He must move to something new and determinately different and separate, hence the importance of not just leaving people behind but also leaving PLACES: his home village for his lycée (secondary school), his lycée for his new home in Amiens, and then Amiens for Paris. Paris is large enough to allow secret changes between districts or to move even to Spain for a week, in the hope of it being forever in actuality, without the people you know in Paris being aware of that abandonment and feeling rejected.

Louis, the narrator, wants to be liked and respected whilst at the same time being free to attach to new people whilst abandoning the old. Hence, in leaving his class origin, he writes to his father, distanced not only by reality but by becoming an imagined interlocutor, in leaving his dearest friend, perhaps a ‘girlfriend’, Elena, he writes to her as similarly imagined as a patient and pliable listener. It is as if Louis wants to make good on his betrayal, if that is what it is, of these now otiose persons, whilst ensuring that they have no independent capacity to knowingly brand him as “une personnel mauvaise”, a ‘bad person’, for they have no agency at all except in his mind (which is some agency but not theirs to control).

That is a believable structure I think for understanding the psychology of rejection from the point of view of the person doing the ‘rejecting’, where it is not such entirely motivated by unmitigated selfish ends. It reminds me of something I was feeling about the character Yelena in Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya (see the blog at this link). In that blog, I saw Declan as Yelena, but perhaps with too much in me of the hint of blame prompted perhaps by sour feelings now passed (but returning like the repressed). I saido f Yelena, with Declan in mind, that she was:

Someone always looking to be at the centre of dramas they self-create. The scenario in Act IV where Astrov confronts Yelena in the McPherson version is powerful. So powerful in production but even in reading. Yelena keeps insisting she must leave but wants not to feel the consequences of doing so, or to push those consequences back onto other people, even her victims:

(McPherson and Stephens are two different translators of versions of ‘Uncle Vanya’) https://livesteven.com/2024/02/15/part-1-of-a-two-part-blog-which-aims-to-talk-about-andrew-scotts-achievement-in-enacting-all-the-multiple-personae-of-vanya-as-aspects-of-the-solitary-and-solipsistic-self-perhaps-part-1/

It’s already been decided. That’s why I can look at you so fearlessly. But I will ask you one thing. Please think better of me than you do. I’m more than you take me for and I would like you to respect me.

In fact Stephens get this even more infuriatingly correct, ending it with the request rather enlarged and asking complicity of the victim of her decisions: ‘I want you to respect who I am and what I want and the decisions I’ve made’).

And yet in the person of Edouard Louis I could nor be so moved to self-pity, for Louis situates his abandonment and rejection not only in imagined explanatory dialogue but in a psychosocial context, that of his his discussion with Ken Loach, not yet translated into English, of the violence of class transitions implied in capitalism and the necessity of socialist art to represent that violence.

For Declan too had sentiments marinated in class feelings that fed off the petit bourgeois aspirations of his family, once shopkeepers on a working-class estate, always seeking to demonstrate they were better than those they serviced, even if they serviced them with kindness and proclaimed high socialist or communist ideals. And, in this he was like Louis, always driven by a desire to revenge himself, but in a kindly apparently gentle manner that was never more than in his imagination. He asks in his imagination only of Elena, the girl who fostered in him his first trial at the bourgeois embodiment of a more refined provincial city than his village, the city of Amiens. He therefore, as does Yelena in Chekhov, demands respect, as ks rhetorically whether he is a ‘bad person’, or a ‘hateful’ one.

Est-ce que je devenais une personne mauvaise ? Est-ce que je reproduisais à Amiens la violence que j’avais exercée quelques années avant avec ma famille, quand je rentrais chez ma mère et que je faisais semblant de lire sur le canapé pour lui montrer qui je devenais ?

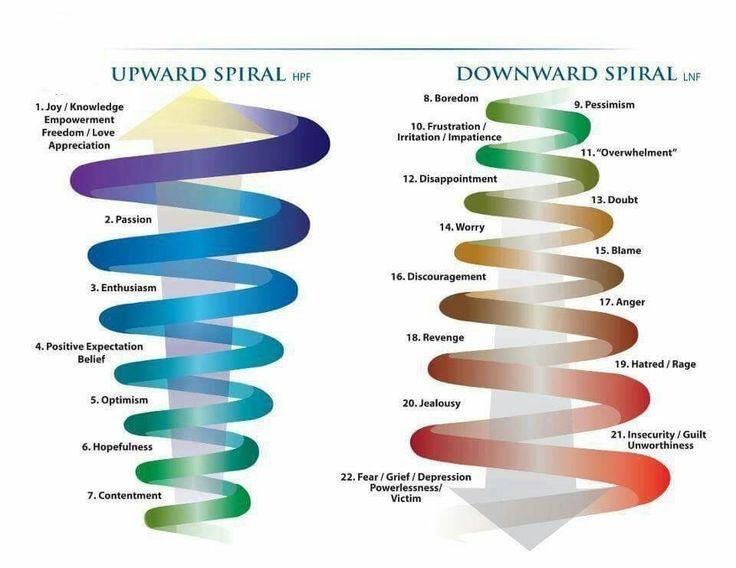

Note that, however, he asks whether he is going to reproduce the ‘violence which he used with his family years ago’ to separate and distinguish himself. It is clear to Louis that he must renew himself – to become better than the present persona, one which when mastered begins itself to seem a trap, a confinement from something better yet. And, though I yearned, as did my husband in a lesser way, for some closure of the relationship which Declan merely terminated (as I say in this raw blog – see link). Reading the in and outs of Louis narrative of changes with its cycle (or inverted ascending spiral as we might think he sees it) of terminations and openings, ends and beginnings, reminded me that Declan actually finished our relationship twice; the first time with some explanation, but in that drunken sprawl in which we sometimes locate the phrase in vino veritas, saying:

I have realised that I can’t know you anymore. I used to be better than this.

Thus in two short sentences I revolve and revolve currently but not now with intense pain, he conveyed that I had become to him an OTHER who had made his self-image spiral down rather than up, that besmirched him with self-recriminations (some extreme ones like ‘rent-boy’, which I have tried to work out in the blog at this link). The implication I felt, rightly or wrongly that the reason for being rejected was some deficiency in myself – ones he had mentioned were sexual inadequacy, not being smart or tidy enough at home or in dress, being overweight or being too involved in pretentious ‘sh*t’. I no longer worry about these things for in a sense any truth in them is situated in a life-long belief that I need not rise to a self-image that the bourgeois world appears to demand of all of us, and which is at its most anxious level in class society in the petit-bourgeoisie, who are stricken with impostor-syndrome. In myself I never fully cut off or end my own Eddy Bellegueule. But then we all are perhaps: it it is psycho-socially what we must be to comprehend and or be comprehensible in the status quo of insecure elites that suppose themselves meritocracies.

So I think Declan, I have found an escape from my sourness in this book, for no one should mourn for ever an opportunity never realised that might anyway have been a chimera. But, dear reader (if you exist), don’t worry for Declan reading this. He blocked me on social media on his final termination and I have tried to block people myself who he uses as his proxies, or has done with other people he abandoned (for I now comprehend Geoff and I were not the first of the same). I don’t fear for him, as I once did, for on those regrettable times when I see social media messages they are professing the same adoration, devotion as he once did to me to varied other men and women. I think that is why I smiled at Astrov’s speech to Yelena in Uncle Vanya (McPherson version):

You know, it’s so strange. I look at you and I see a well-intentioned, warm-hearted person, yet everywhere you go you wreak havoc.

Well I hope that means I have a free go now at a proper appreciation of Change – hopefully in the next blog, for it is a great novel in its understanding not only of the violence of class exclusions and transitional struggle, between groups and within the constructed persons (each one) inhabiting those interactive spaces, but in those created by false binaries (and subordination of the disfavoured element of the binary (women in gender, black in abstracted categorisations of race) implicit therein) of sex/gender,interactions between cultures and races, and, relationships between normative and non-normative sexual paradigms.

Bye for now

With love, Steven xxxxx

________________________________________

(1) ‘My father named me Autolycus; who being, as I am, littered under Mercury, was likewise a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles’. Shakespeare The Winter’s Tale IV, 3, 1724ff.

One thought on “The feeling of rejection and abandonment: a personal case study.”