In Andrew McMillan’s Pity (2024) personal memories and socio-political histories meld so much that they are perfectly expressed in the same metaphors, as concerned with that which, ‘came back to him every so often, when the wheel of memory dredged it up and brought it into the light and then sunk it down inside of him again’, whether in the case of Simon, a central character of the novel or its older Barnsley characters.[1] This is a blog on Andrew McMillan (2024) Pity Edinburgh, Canongate Books.

N.B. IT CONTAINS SPOILERS. BEWARE UNLESS THAT DOES NOT SPOIL YOUR PLEASURE IN GOOD BOOKS.

On this occasion I want to start this blog with the title quotation and its context. It comes from a section in which Simon speaks of the consequence of leaving his mobile in the ‘temporary classroom where they taught history in secondary school’. It is a gratuitous beauty of the spare prose of this novel that the temporary classrooms that blight underfunded schools are themselves a problem in ‘history’ that doesn’t get explicitly taught in the classroom. And history’s wider reach does not stop with this cunning temporality into which it is cast in post-Thatcher Barnsley: Simon’s text messages to another boy (Simon, is one of the main characters of Pity) are read and he is outed as queer. His distressed responses mean he has to again ‘come out’ to his teacher, a man struggling to make sense of his role in the light of the cancellation of talk of queer sexualities in schools enshrined in Section 28 of the Local Government Act.[2]

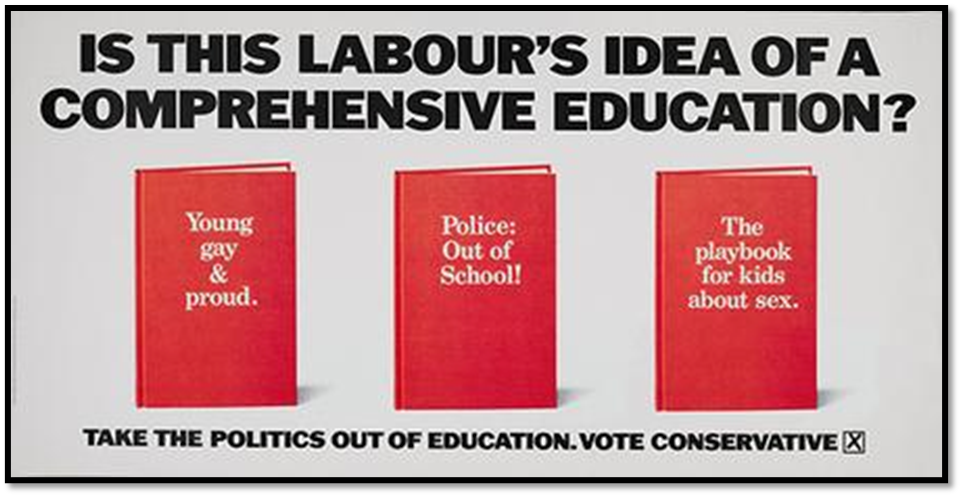

A Tory Party poster from the 1987 general election campaign, the year before Section 28 was enacted.

The intersection of persons, differentiated identities and their markers and the symptoms of socio-political economic and historical change could not be clearer than in this example. Speaking to Nick Levine in an interview for Another Magazine in February this year, however McMillan claims this experience – of self and history for himself, in words very similar to those of the novel:

AM: … When I became aware of Section 28 retroactively, suddenly everything made sense in terms of how I moved through school. When I was in year ten, I went to lunch and left my phone in the classroom – there were no locks in those days, so somebody read these quite explicit text messages I’d been sending to a lad my age. When I came back, it became obvious everyone had read the messages and I remember breaking down crying. I was a nerdy student, but for the first time ever I refused to go to class. Then a teacher took me to his office to find out why I was upset. I always remember he took a breath, said “fuck Thatcher!“ and then carried on helping me. All of that only makes sense now in retrospect, and I actually give that bit of my own story to Simon in the book. I also think that we [as a society] need to talk about how cyclical these things are. The rhetoric being used now against young trans kids – all the scapegoating and fear-mongering – is the same rhetoric Thatcher used in her 1987 speech where she talked about kids being taught they have “an inalienable right to be gay“. It’s absolutely horrifying to see that rhetoric coming back.[3]

This is a wonderful passage in which McMillan makes a passionate stand within his own communities of identity and belonging, for he makes it clear that history repeats itself through the recycling of rhetoric – words that shape values and with those, events large and small in the lives – recognised as of national significance or not. Being caught in the dynamics of the web of queer history is a confusing thing for so much of it is seen not as ‘history’ but as JUST a set of ‘personal stories’. Sometimes history, in this context, has to be actively mined, even if we do not know why we are thus cast in the role of its miners. That memory is one that, for Simon (and presumably for Andrew McMillan) ‘came back to him every so often, when the wheel of memory dredged it up and brought it into the light and then sunk it down inside of him again’.[4]

I shudder a little at writing about the dual reference in this important cusp between the novel’s concern with both histories and selves, for in another interview, with Alice O’Keeffe for The Bookseller, he insisted that he took pains to ensure that it was not seen as ‘my experience in the novel’. To do so he says in 2023 that he made himself a character in it – and having been to a teaching event he gave (at Todmorden – see my blog here if you wish) I can attest that the self-description of the public persona (one that still feels to the receptor of .the practice of his public teaching as if had some connection with you) is spot-on. O’Keeffe records him thus:

McMillan himself has worked as a writer-in-residence in the community and actually wrote himself into the novel as a poet who visits the working men’s club to run a workshop. “It’s not auto-fiction and it’s not my experience that is in the novel, so I thought the best way to get that across was if I had a cameo halfway through,” he jokes. Community writing projects are sometimes maligned, but when they are good, he says, “it’s not about getting them to write in a certain way, or anything like that, it’s often just about allowing a space for [participants] to examine language”.[5]

Jokes and half-truths are, I think, specialties of that persona moreover for, if the book is not ‘auto-fiction’ exactly, he certainly (as we see from his own mouth above) uses his experience. That he shared the personal source of the experience only with a queer-orientated publication and its audience is typical. Such audiences will recognise where personal memory are in fact accounts of queer political history, where queer people have commonalities with each other as well as intersectional differences. But it is playful to use that reference just to point out that there is a useful role for artist-in-residence placements. In the novel the person, who in the account of the novel, is solely named as ‘the poet’ is also he, whom McMillan in a piece in The Guardian says, is ‘a young poet with an armful of tattoos who may or may not be me’,[6] momentarily picks out from the class the sceptical working-class brother, Brian, of Simon’s working-class father, Alex, and discourses with him on the difference a relative point of view makes to what ‘history’ looks like. What prompts this is Brian’s account of what the view of what history might be from the perspective of the anthropomorphised ‘away end’ grandstand at Oakwell (the football stadium):

“That sounds brilliant!” the poet replied, beaming. He looked over his shoulder to the other researchers for reassurance, and they smiled and nodded too. “I love that idea,” he went on, “I think it asks such an interesting question, doesn’t it, of history? The big event happening in one place, but what if we look somewhere else, what is that we see then?”[7]

Brian, of course, treats this rhetorical question as if it were not one, but the humour here is really directed at the earnest middle-class academics, even if they once were working-class in origin, with ‘an accent’ as Brian here thinks, and as I suppose I did in Todmorden, ‘that seemed as if had begun here but flowered elsewhere – familiar and yet not at the same time’.[8] The author skewers his identity at the moment of its temporary showing as an aspect of personal identity histories and variations with context which it is part of the novel’s overall take on those marginalised and otherwise, permanently or temporarily, in its processes. It is a brilliant and moving moment of self-analytic self-inclusion in the problematic sphere of the dynamics of historical transition. Any writer should be PROUD of themselves for accepting this truth of the fact that we are truly all in this together. If not as David Cameron mis-meant it.

Barnsley Main Colliery

But if we are all in it together, I find the treatment of this novel in the press rather keen in un-queering or marginalising its content. Thus Declan Ryan in The Observer in an otherwise empathetic review treats the queer themes separately from the ones about Northern former-mining communities. He is clever of course in noticing that the university project in the novel is ‘examining the town’s collective memory of its mining years and the enduring trauma – like the mines that squat, dormant, underground – remains a constant but unacknowledged presence’. He says too that it is ‘at its sharpest when exploring and enlarging notions of community’ and yet feels the novel feels ‘a little heavy handed’ because of its ‘carousel structure’ which, to him, ensures that it ‘overrides subtlety’ and ‘signposts its unifying symbols’, like that which link Simon removing the layers of his drag persona, ‘Puttana’, after an event in a club. [9] So much of this qualified praise seems to me rather an attempt to ensure the cultured reader remembers the supposed truths spoken by Keats: “We hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us — and if we do not agree, seems to put its hand in its breeches pocket. Poetry should be great and unobtrusive, ….”. How vulgar it is to be unsubtle and to ‘signpost’ one’s intentions as an artist.

Although it is not found in Catherine Taylor’s lovely and vastly intelligent review in The Guardian, which gets the great ambivalence historically of Margaret Thatcher’s role in the history not just of mining but of historical constructions of sex/gender, damning with ‘faint praise’ is I think a trait of some literary journalism. The latter is often thought de rigueur for its male practitioners, but I think it a version, when used in this context, of the power of heteronormativity to still oppress. In Declan Ryan’s review, that feature of his possibly unintended thinking, pretends that there are clear dividing lines between the metaphors appropriate to the examination of how marginalised mining communities like Barnsley’s (or much of County Durham) have changed in time but remained marginalised to the hegemonic culture. Behind the lines exploring sex/gender/sexuality phenomena, such as an interest in drag or the necessity of secreted sexual contact-making that marginalisation are not appreciated by Ryan or seen, at least, as linked. For queer young people abandon the traditional North to find versions of it in metropolitan (and often Southern) ‘elsewhere(s)’ (places we leave the community to get to). We need to remember of course that the ‘young poet’, Andrew, did leave Barnsley, to tell truth both in class and geographical terms, if not in artistic ones (for his father was already a well-known Northern poet, adopted not only locally but by the BBC). Andrew though is now a Professor of Creative Writing and Literature at a Manchester University.

However, Nick Levine says that McMillan insisted to him that this novel though should not be ‘about leaving’ but building a life in one of these towns where queer young people like Simon and Ryan) or middle-aged ones (like Simon’s Dad, Alex) ‘can be accepted there and feel artistically fulfilled’.[10] The symbol of this in the novel is the story from the mining past of the miner’s love of homing pigeons, released to stray confident it will return as a result of ‘whatever instinct was bred into it’.[11] In this respect it mirrors a contemporary queer novel, by Jon Ransom, that I have blogged upon recently (use the link here if you wish). People leave towns like Barnsley for lots of reasons that are embedded in its histories: its lack of an economic base and superstructure, its social marginalisation (in part interactive with the fact that young people in particular leave it), its unappealing look because of a lack of maintenance and self-esteem, even its obsession with a limiting version of its own history (in its school with their temporary classroom) as of that of a heteronormative working-class, whose heteronormativity was often a mere invention of ideological and right-wing takes upon history, especially of the history of the working-class. Hence the suppressed history of working-class women even is invoked in Simon’s construction of his drag personae to satirise Thatcher, finding almost accidentally a song ‘Women of the Working Class’, that he had heard at ‘some event’ he visited in Durham ‘a good enough audio of women singing’. Thus Simon’s self-making can barely be said to be used as merely signposting a theme or palpable design of a political nature upon us.

The point that McMillan never tires of making in this novel is that it is about not just community, but narratives about community, and the insistence that these are multiple in origin and ‘point of view’ and that some of those narratives are considered to be both insignificant or merely personal in mainstream culture, or even perhaps just secondary to the main themes of history. In the novel, he brilliantly puts this idea into the head of the secondary school headmaster whom the university academics approach to host their research and agrees initially ‘as long as’ their ‘plans showed how the work would map onto the Year 9 academic expectations’. Thus it is that marginalised historical agendas are forced to map themselves onto others than change essentially what are the ‘big’ narratives of history – of government, civil society, class and politics (narrowly understood). For when the academics go onto say that they wanted in this process of teaching and learning to ‘turn control entirely over to the students’. The headteacher makes it clear that his version of the conduct of ‘history’ (as a subject) was determined by his doubt that young people could ever ‘respond well to freedom’.[12] Clearly history can no way be a dynamic force in this moment of its reproduction with a difference.

And yet narratives of history keep unfolding and the world in which it unfolds changes selectively in response, a fact that is registered in this stunning sentence: ‘like a roundabout at the centre of a disused road, the club had stayed constant while things around it shifted’. Things may change in structure, function or merely by the language that names them, in whatever way the built environment looks like a series of layers (like the underground strata of a coalfield) with old and new, constant and shifting finding themselves in different interaction with each other. [13] This idea is articulated, especially in the Field Notes, by showing humans performing ‘mapping’ activities, which are described or pictured in spatial-temporal manner, as when Brian sifts memories of places and people to place them on a temporary map made of cards on the ‘sticky wooden top of the club’s longer tables’. Yet these maps are of places imagined, existent ‘only in the few years he was trying to map … almost as though he was walking down those streets again, …’.[14] This means of realising the past in physical terms estranges its subjects, but also makes them aware of what links to person and places might still be potentials for later re-emergence: ‘It was strange seeing his past flattened out and laid out like that, as though someone had unfurled a tablecloth on it’. Of persons named and remapped on that flat map, he realises: ‘They hadn’t really left; he supposed he could keep in touch with them if he tried’. But some people have LEFT, either through natural or less natural processes of mortality (for some men with the same names of their survivors die in terrible catastrophes – in pit falls for instance whereafter: ‘There are mornings nobody steps out’).[15]

But some bits of history, especially queer history, are lost, known only by the queerest of exceptions that survive. The process of young queer men leaving South Yorkshire, would if universal, have left Alex not only without a son, as he loses his wife, but a model for reinventing his own queer sexuality that had been squashed at his school. But instead his son, Simon, and his son’s lover, Ryan, encouraged him to re-explore in a more open and visible way his own secreted (nay buried) sexuality and gender differences. Nevertheless there are lots of way Northern towns invent their examples of a ‘portal to elsewhere’, even if it once was just in ridiculously expensive Pollyanna shops[16]. I think Catherine Taylor in The Guardian grasped this when she says, that though this novel registers the history of mining communities in its difficult periods in the 1980s, including their divisions, but other less public histories:

Pity is a book about male identity and sexuality whether anxiously concealed or proudly open – and about the ravages of history and politics, mostly significantly on the working-class towns and cities of South Yorkshire such as Barnsley and Sheffield.[17]

What Taylor does well here is to show that the primary histories in the book of sex/gender variation amongst local families, communities and their hinterlands in time and space are a part of the whole web of mutual influences that are the ‘ravages of history and politics’ including pit disasters and mining strikes, economic neoliberalism, revolutions and reaction in sex/gender politics, even at the level of the masks of persons like Thatcher, and, patterns of regular life among varied people and their disruptions. Queer history has not left the building, or its home town, in this book. Indeed parts of it are rescued and reinterpreted as in the lovely story of the Andrew Dobson House Museum and its participants.

The Maurice Dobson Museum at Darfield, outside Barnsley: https://www.darfieldmuseum.co.uk/ . See ‘Pity’ pages 109ff.

This is not to say, in case of any misunderstanding, that both queer histories and folk histories of South Yorkshire are rendered unproblematic. Nasty subdivisions exist in both communities and histories. Even a version of state surveillance (symbolised in the role of CCTV in the novel) has its equivalent in queer community ‘gossip’. Moreover, in a book like this, issues of race and ethnic diversity become problematic. There may be room in such a novel for looking at this, though the communities of South Yorkshire do still possibly live in as segregated ways as this novel suggests they must. McMillan is aware of this because he cites Sunjeev Sahota’s treatment of Sheffield Asian communities in his Guardian article, but in Pity, there are few pointers to the issue. There is one I noticed – but operating under such cover that it concerns: wherein a participant in the mapping exercise writes down ‘a couple of nicknames for local shops which they clearly rather he hadn’t’, the only reference to the lingering oppressive naming in South 9and West) Yorkshire of ‘Paki shops’.[18]

The most interesting aspect of how histories integrate around themes is in the treatment of the histories of different kinds of social surveillance, especially those aimed at the eradication of non-normative behaviours. Even the young queer man, Ryan, in his work as a surveillance officer in a security firm likes using CCTV to eradicate men who have sex in public toilets, playing a kind of knowing game with them in which he enjoys his power of breaking up such unions, instilling fear and making people ‘leave’. Queer gossip in pubs acts as surveillance – that is enshrined in the pattern of chapter headings which are either ‘surveillance: CCTV’ or ‘surveillance: gossip’. It lies too in decisions that in sex the binary of private and public is continually drawn, if sometimes reconfigured. Thus the body of the participants, including Ryan, can be cut off in those videos to escape identification, whilst Simon smiles away on them and sells that smile as a commodity. Alex warns his son and Ryan against public shows of affection between them as men, whilst yearning for the same. Alex is caught on a CCTV camera he didn’t know about outside his club showing his desire and fear of entry int it on the night Simon is doing his drag show. Simon often manipulates what he wants to be seen of himself, sometimes alongside a mirror motif, such as when he sees himself in a distant mirror, ‘tiny’.[19] He uses a ‘mirrored wardrobe’ to regulate the seen and unseen in his best video with Ryan.[20]

For McMillan, and this rang bells for me too, the history of the gaze, and consciousness of the gaze upon you has run through his history as a queer man. He said to David Levine, in a brilliant paragraph:

the experience of growing up young and gay in Barnsley, to me, carried this feeling of being constantly surveilled and looked at. Whether it’s in your head or not, you do just feel hypervisible. And so by having scenes where a character watches another on CCTV and even the OnlyFans scenes, I could convey this sense that they’re constantly aware there’s a gaze on them.

But the role of the gaze is functional in other histories too, like that of the public surveillance of survivors of mental health systems and those dubbed criminal or politically unsettling. Of course some things are kept away from the gaze. This is the role of the mine in part in the novel – a world of men buried in history in so many ways. The scars of history lead, the academics tell us to ’social haunting’, a return of the repressed as a resistance to that oppression (in pride) and / or to manifest social, physical or emotional pain and abuse.: ‘What is concealed, beneath the ground, still very much alive and present, still breathing, still prone to cough, to slippage, to subsidence’.[21] This is as much about sex/gender/sexuality, as community fracture and the physical politics of mineworking itself. Hence that beautiful extended metaphor that emerges in the example in my title: ‘, ‘came back to him every so often, when the wheel of memory dredged it up and brought it into the light and then sunk it down inside of him again’ It refers to that memory of school Simon shares with McMillan himself, but it is also about the complex issues on the surface and concealed in that chapter regarding the resurrection of memories of Margaret thatcher as a neoliberal politician, a sexual politically reactionary and a force in the coming to awareness that gender appearances, including audible ones, are manipulable.

And this brings me to my favourite little theory I have about the novel’’ title and its relationship to Puttana (obviously as she is as the imagined sexually open sister of prim Pollyanna, shop as in the book, psychological principle and myth in fiction), Simon’s drag persona name. Explaining it to his Dad he says the name comes from a ‘funny, sexy character in’ a ‘play they’d done at college’. The character, Putana (as it is in the play) is from, the name Putana being derived for the Italian for ‘whore’ or ‘prostitute’, John Ford’s play ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, which ends with that very phrase attempting to put all the blame for an incestuous relationship on a young woman within the relationship, Annabella, and her servant-cum-mentor, Putana. The latter is blinded before being put to death rather than her brother or all the other men who act appallingly in it to her and each other. That, I suppose, is the genesis of the historical Pity that runs through this novel – oft a mask for cold-blooded lack of care for the scapegoated, who get blamed for not following rules not in their interest. Hence Simon’s phrase ‘This turn is not a Lady’ true of Thatcher and Putanna in very different ways. In a sense Putanna is a mask to enable Simon to be looked at and look back without being an object of Pity, but of pride in himself and his welded communities – or working class people and queers. In the beginning Ryan, his lover, doesn’t get that. For it all comes back to HOW one confronts the gaze of surveillance and norm-checking. After Simon does not quite remove all his makeup, Ryan looks at him askance:

When Ryan had looked at him, with what felt like disgust, he’d suddenly felt conspicuous again. Not visible as Puttana, but visible as himself; … . He didn’t know how to explain that to Ryan, that to be looked at, and who was looking, were these complex turning cogs that lifted panic up into his mind or sunk shame deep down inside him

The metaphor of the sunken man condemned to the operation of the cage in a mine shaft is that of my title quotation. The Pity of it all is not that Simon is a part-time prostitute on video but that he is blocked from showing his sexual, romantic and bromancly feelings in public. Pity.

With Catherine Taylor however, I do want to contest the view that the poetic prose of the continual pieces on old Barnsley mining – that period preceding Alex and Brian even but of men with the same names – is as Declan Ryan sees it as: ‘the most poetic parts, albeit at times tonally off-kilter: the sky is “a threadbare sock of grey”’. Is that ‘sock’ really off-kilter. After all it uses the pun of wind-sock and foot sock deliberately to meld the ordinariness and dreariness of this scene and to emphasise its repetitions where variations, like the sock, come as a bold surprise. The passage that begins ‘He steps out into the long corridor of early dawn’ appears 6 times (and recall a lyric from Tennyson’s In Memoriam -whether on purpose or not), each time opening up differences and eventually totally shattered by the breakdown of regularity by the death and burial underground of its characters in a pit-roof fall. For me, to rule the tone of such passages off-kilter to readerly expectations is a huge mistake. They are central to the idea of the inheritance of ‘social trauma’ but they highlight recurrent (because inherited) feelings of underground whispering and of darkness outside of corridors we thought of as light that run through all the experiences in the novel.

This is a wonderful novel and it grows on you. Read it.

With love

Steven xxxx

Andrew McMillan. Photograph: Sophie Davidson

[1] Andrew McMillan (2024a:40) Pity Edinburgh, Canongate Books.

[2] Ibid: 40

[3] Nick Levine (2024) ‘Pity: An Evocative New Novel About Queer Life in the North of England’ in AnOther Magazine (online) (FEBRUARY 05, 2024) Available at: https://www.anothermag.com/design-living/15401/pity-book-review-andrew-mcmillan-author-interview-2024

[4] Andrew McMillan (2024a:40) Pity Edinburgh, Canongate Books.

[5] Alice O’Keeffe (2023) ‘Andrew McMillan in conversation about language and narrative in his début novel: “It’s not that people didn’t have bad experiences, and small towns can be really hard places, but that’s not the only narrative.” In The Bookseller (online) [OCT 13, 2023] Available at: https://www.thebookseller.com/author-interviews/andrew-mcmillan-in-conversation-about-language-and-narrative-in-his-debut-novel

[6] Andrew McMillan (2024b: 45) ‘The View From Here’ In The Guardian (SUPPLEMENT) [27.01.24), 43 – 45.

[7] Andrew McMillan 2924a, op.cit: 96f.

[8] Ibid: 94

[9] Declan Ryan (2024) ‘Pity by Andrew McMillan review – an excavation of identity and collective memory’ in The Observer (Sun 4 Feb 2024 13.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/feb/04/pity-by-andrew-mcmillan-review-an-excavation-of-identity-and-collective-memory

[10] Nick Levine, op.cit.

[11] Andrew McMillan (2024a): 93

[12] ibid: 31

[13] Ibid: 18

[14] Ibid: 27

[15] Ibid: 148

[16] Ibid: 51

[17] Catherine Taylor (2024:50) ‘Hidden histories’ in The Guardian SUPPLEMENT [10.02.24] 50

[18] Ibid: 27

[19] Ibid: 37

[20] Ibid: 135

[21] Ibid: 85 – 86

8 thoughts on “This is a blog on Andrew McMillan (2024) ‘Pity’ Edinburgh, Canongate Books.”