A day in Edinburgh with Prints and Photographs: Exhibitions in National Galleries of Scotland: (3) Making Space for a Reason. But what reason? (Part 3 [FINAL PART] of Edinburgh blog).

For Part 1: A day in Edinburgh with Prints and Photographs: Exhibitions in National Galleries of Scotland: (1) Introduction; use this link.

For Part 2: A day in Edinburgh with Prints and Photographs: (2) Hidden ingenuity and affordances to thought and meaning in the Art of Printmaking: use this link.

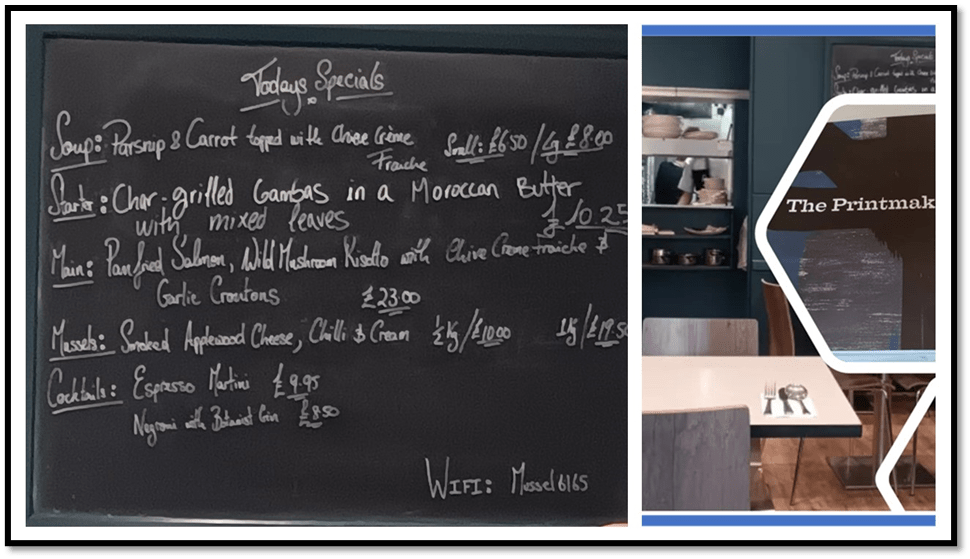

Part 2 ended with me choosing lunch from the specials on the board below and reading as much as I could of The Printmaker’s Art (if you are interested in the lunch I started with the Gambas and then had the Panfried Salmon). Rose Street is a street I love to walk – because it was once the drinking haunt of favourites amongst the Scottish poets who gathered around Hugh MacDiarmid. Hence after the National Gallery I had walked down to Waterstones on Princes Street, just to walk Rose Street back from end to end, selecting a spot for lunch on the way.

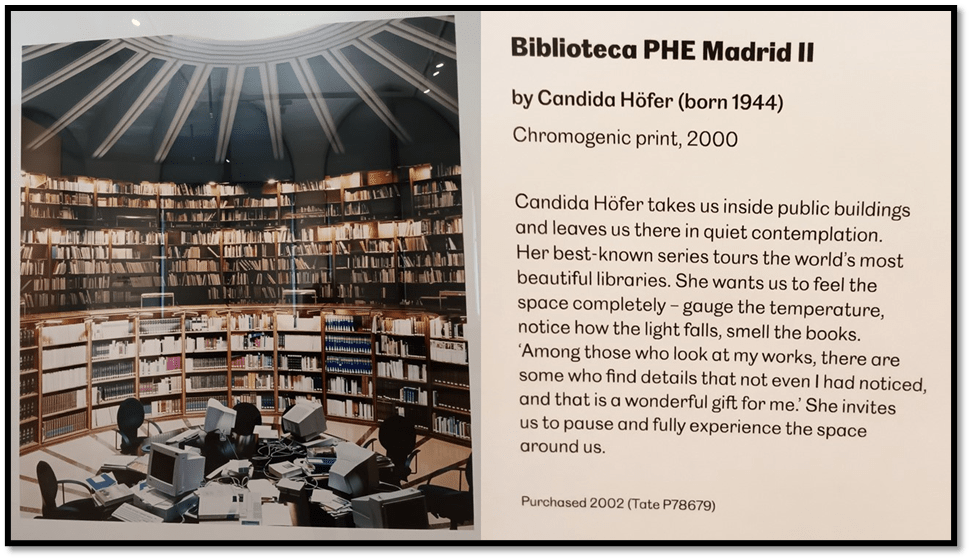

Then to St. Andrews Square and down to the Portrait Gallery, that wondrous concoction outside and in of mock Venetian Gothic in warm red brick and very wooden interior frescoes. My aim was the current photographic exhibition (just one large room but it was free entry) called Making Space: Photographs of Architecture.

In truth, I suspected that that my interest was not really in architecture as such and neither, I think, was that of the exhibition despite some of its curatorial commentary. Architecture can I suppose be thought of merely as a configuration of spatial relations – it creates insides and outsides, often in complex interaction both in te appearances of the thing and the thing itself. Hence the excitement added to architecture by the use of glass and the reflective function of glass.

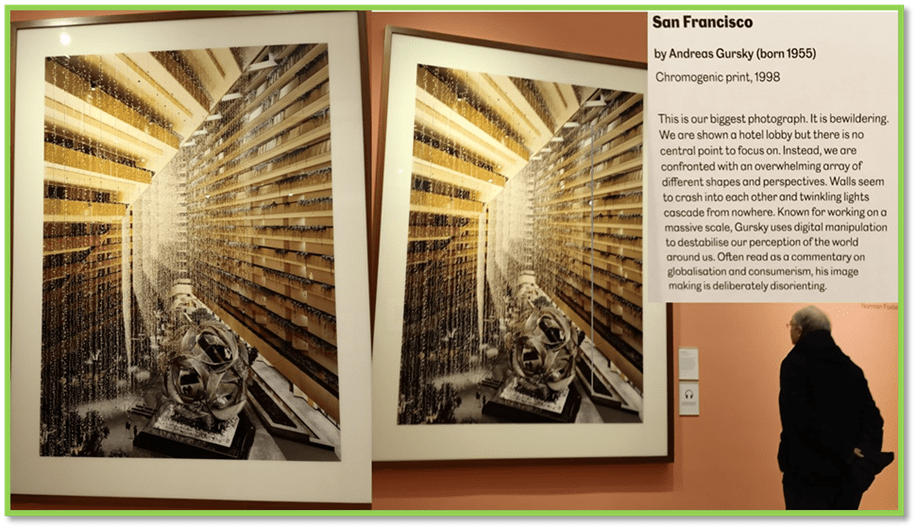

Appearance alone though can be deceptive enough, and one star of this show was precisely about this – the largest piece is a huge vista of a built space, a hotel lobby, in San Francisco and called that, as a work, San Francisco. It is a strange title – perhaps intended as a metonymy – where a part is seen as a means of apprehending the whole metaphorically, San Francisco as a place of illusion in transitory space – for people merely cross over each other in a hotel lobby – but that would, in a photograph be an unfair presumption. I don’t however, here want to look again at the difference I see in places and spaces, for it’s a theme I’ve trawled too often in these blogs recently (see example at this link). The plaque describing the work is probably correct in seeing it as Andreas Gursky, the photographer’s play and interaction with illusory space that was already a feature of the architect’s plans. In the collage below get a feel of the size and look of this piece.

If architecture and photography share an interest in the illusions that contribute to looking and seeing, that might in itself be a good singular theme of this show, but the show, for good and ill has no such singularity. It also wants to look at architecture as a negotiation of public and private space – hotels being already a transitory form in that binary, that will include temples and cemeteries, palaces and a part of a football stadium, libraries and a swimming pool as well as social and private housing, living spaces or, as Corbusier has it, ‘machines for living’.

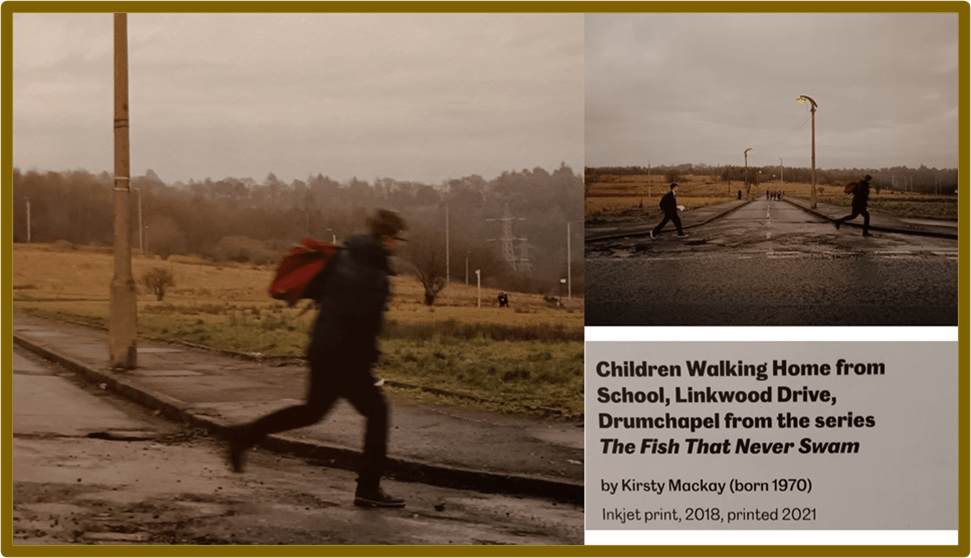

And if that were not enough it must look not only at the incidence of how physical space looks at any one time (1998 for San Francisco) but at photography as a negotiation too with temporal space – a way of negotiating past, present and future. Add to that a social conscience – one photograph – the lovely one of Children Walking to School (in 2018) by Kirsty Mackay, has a commentary plaque mainly dedicated to the social effects (on life expectancies of children) of the environment. Except, of course, it’s not just the environment, I wanted to debate with the plague – its entire social systems of the distribution of opportunity, work, leisure, personal and public space and time. Of course exhibitions can’t do it all. But look at the photograph, especially the enlarged detail from it I select in my collage below.

One of the beauties of that photograph is the contrast between the two boys on either side of the blank road through a bared landscape. The boy who begins to run, is blurred by the effect of a motion that has been stilled by a shutter time too slow to not represent him in more than one spatial-temporal moment. Instead, we get him registered in the interaction of motion in passing time with the singular time of the shot. And that issue about time, and the passing of children in it, is a deeper take I suppose on life expectancy, and reminds us of another feature of photographs in the exhibition. They record one time and make it survive for later inspection when the thing they record has passed or changed its function – land may be built on, children grown to adults (or dead – long so). The architecture may have lost or changed its meaning.

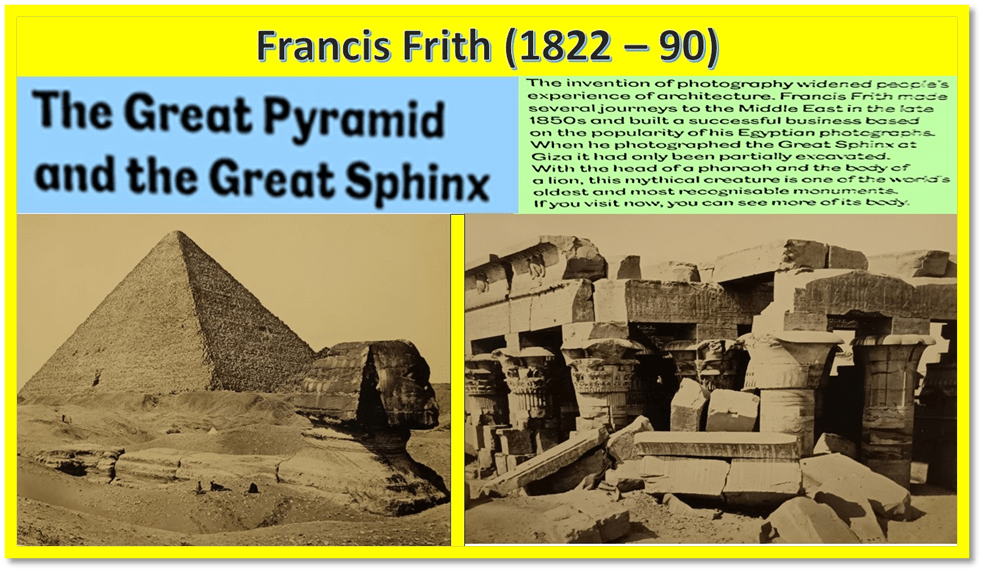

Hence the exhibition begins with monumental architecture not only forgotten in time but partly buried in its effects. Look at the Frith examples below (amongst the first you see).

The commentary on the plaque doesn’t help me. The least interest thing about these photographs is the exposure of Western cultures to long dead Semitic cultures, although it is of interest that Frith could commodify and grow rich on the interest of the mid-nineteenth century bourgeoisie on an ancient aristocratic culture and theocracy long dead and gone. Those temples and monuments are interested because their depths (excavation is a theme of them – the resurrection from buried time recorded in the intervening trenches and signs of recent digging ) and dark interiors, full of mystery and signs that access into them was not safe for the person who merely views their obscurities instead. Did Frith remove the people who had been recently digging. These scenes are empty – in reality they would not have been. However the long exposures required of cameras in the 1850 may, for Frith have necessitated, he use his status to remove local and badly paid workers on the scene for a while.

Nevertheless what is recorded is dead space, not a ‘machine for living’ but a memento mori. And we shall see that them played on as a symphony in other pieces. I neglected to record the name of the photographer, but one shot of a colonnade in an Indian palace not only exoticises it subject but in using a shot that is very near as possible to a negative makes architecture seem as spectral as the people it once served as living quarters.

Even the vegetation is spectral – barely living, as if the past were a haunt of vampires sucking the blood of the present. And, of course, this was a favoured theme of the nineteenth-century (Dracula was not fearsome I suppose just because he was undead but because he was a Count, a morbid aristocrat, trying to regain his great social power in a time given over to the world of middle-class industrialists and exploiters of the poor in their own much less responsible manner). The Empire was, in truth, intended to impose such ways on powerful landed feudal lord but rather more quickly than in British history.

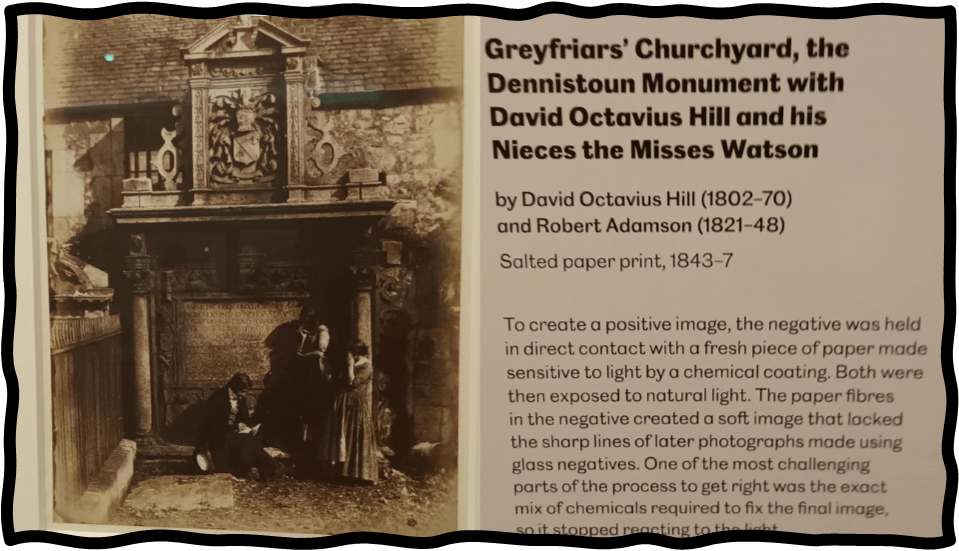

Nevertheless photography would record social lives with some responsibility too for those not advantaged by the new wealth sources of the nineteenth century. David Octavius Hill and Rober Adamson recorded Edinburgh as a place of social transition that ensured much inequality, injustice and oppression. They used photographs as a social record. Yet the choice from them in this exhibition shows them too in a moment of reflection on the passage of personal and social temporal space, recording the great achievement in public sanitation that were the cemeteries of Edinburgh.

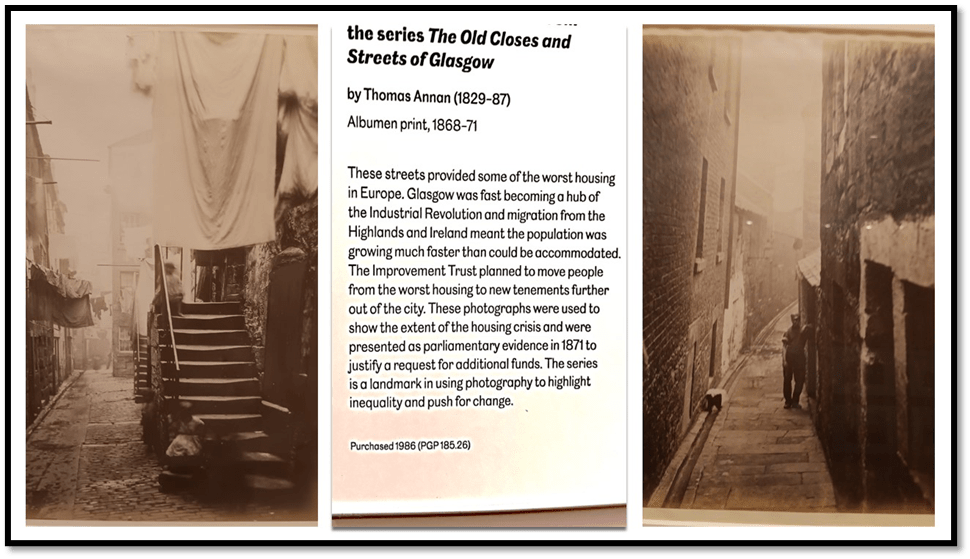

This one of Greyfriars is a case in point, and although the commentary rather overconcentrates on processing techniques, what feels to matter here is the symbols of a leisured class, now themselves recording a moment of well past time and manners, honouring a rather different florid seventeenth century past in one of the older mural monuments in what was a new development in public space – hygienic burial of the dead. Adamson and Hill were locked in by class. But an interest in public space is shown in some wonderful pictures of the old CLOSES of Glasgow, where poverty held itself private from public concern.

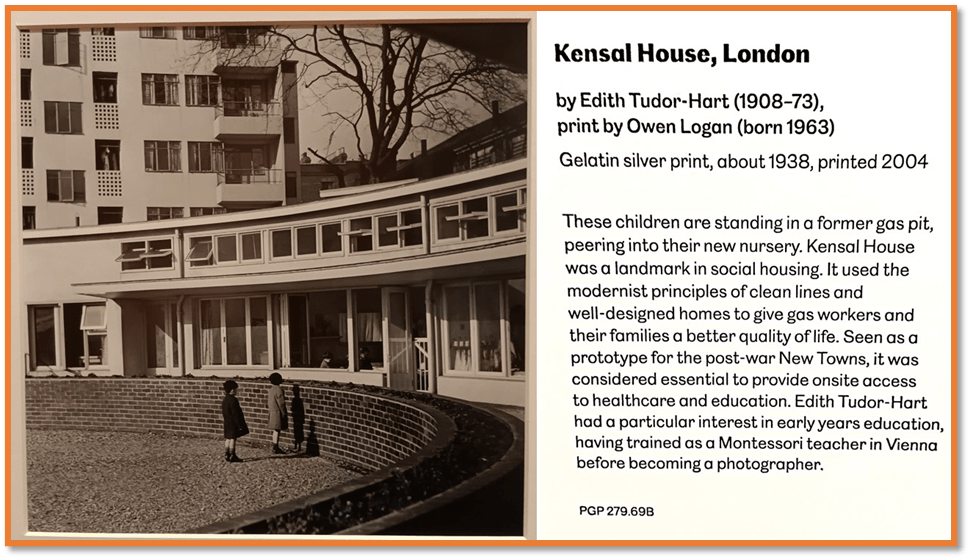

Annan’s concerns were not to present the present as a picturesque memorial for the future to have these spaces eradicated or reformed by new, safe and hygienic housing for the impoverished working-class aided by Improvement Trusts. It is difficult to see them now though quite in that light. Their grainy textured feel seems to validate the actual misery they were intended to record as something of sentimental interest. In London too the same occurred. Edith Tudor-Hart’s photograph of modern replacement living now harks back rather strangely now that housing , often rapidly built and not involving those it housed, have become our contemporary slums. There is something wistful about the children stood, in what once was a ‘gas pit’ staring into new public architecture meant for the benefit of their class as a whole, something sad.

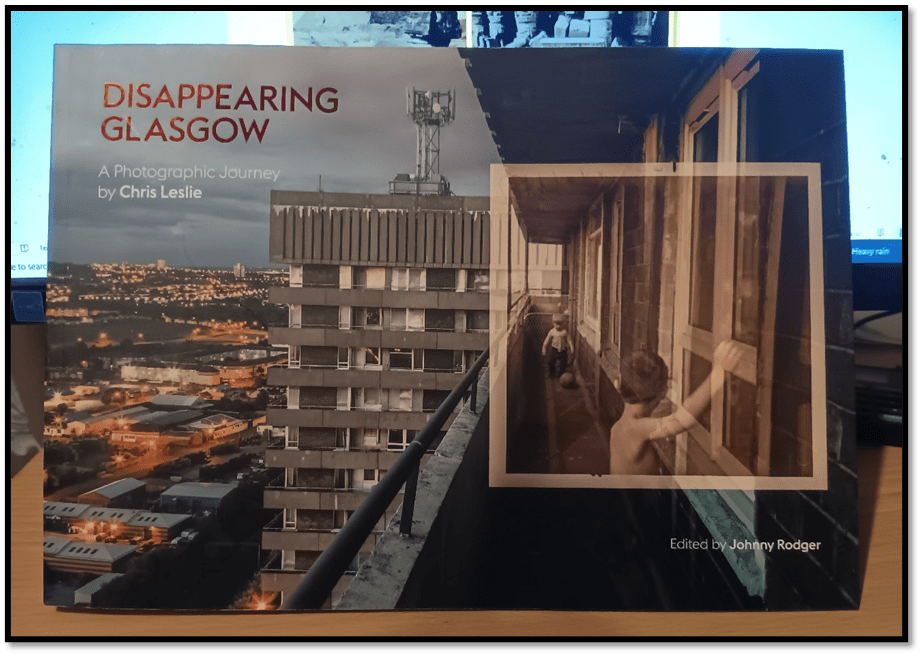

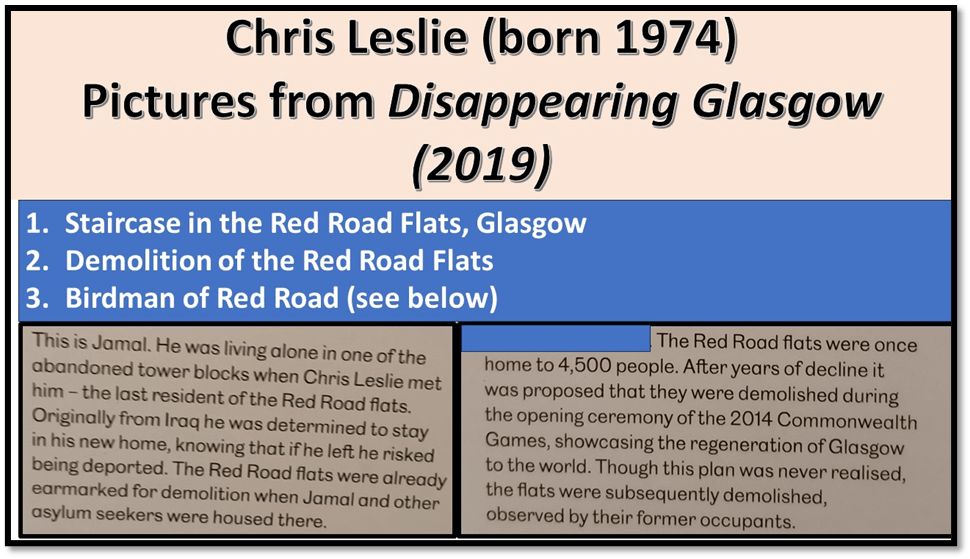

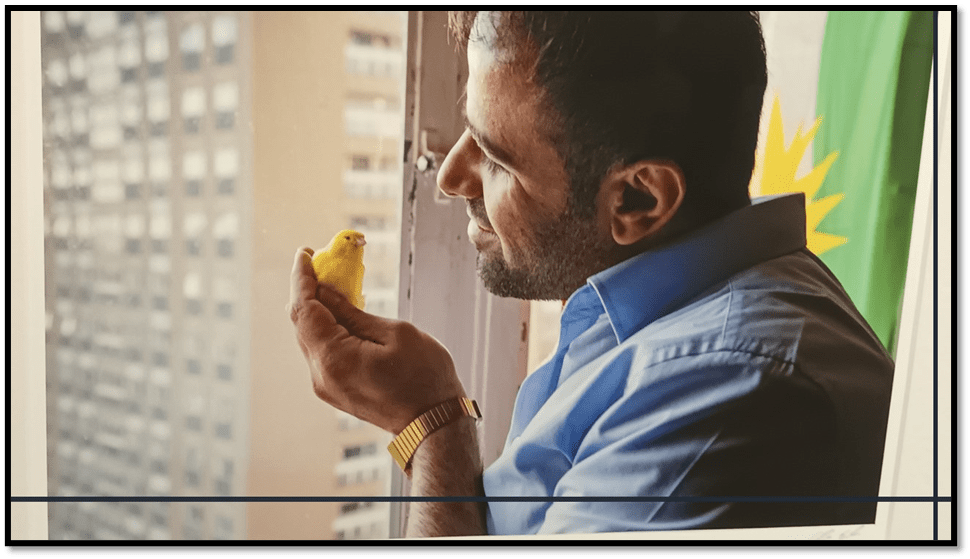

One motive I had for visiting this exhibition was to see originals, presented at exhibition size of the photographs of Chris Leslie, who recorded the removal of the various Glasgow high-rise schemes and raised estates built to replace the closes, now themselves considered an eyesore and repository of social evil, and removed with as little care for their residents as were the closes. I have a lovely copy of his Disappearing Glasgow (2016), here resting against my PC screen as I type this, which sets pictures of the schemes in their functioning as ‘machines for living’ against their immediate pre-demolition reality. And they were demolished without care for the fact that the housed refugees, who accepted inadequate housing for nothing better was on offer. This is the meaning of Leslie’s famed Birdman photograph. The Labour Corporation wanted the Red Row flats to fall as part of the spectacle for visitors of the Glasgow City of Culture celebrations. Enough said.

Chris Leslie’s work speaks for itself. In semi-demolition, a scene that shows a window view also shows rooms whose floor and ceiling separations are gone but the records of once-inhabitation remain. This is one the most profound pictures of architecture I know, where interior space has so many meanings and feelings attached, ones hard to read but like lives inscribed on walls only to be destroyed. That window view is surreal in its effect. This is what I came to see.

Of other Leslie’s, they can genuinely just be recorded as there. My poor reproductions can’t do them justice – there are many more in the book. But see the large ones at the exhibition itself if you can.

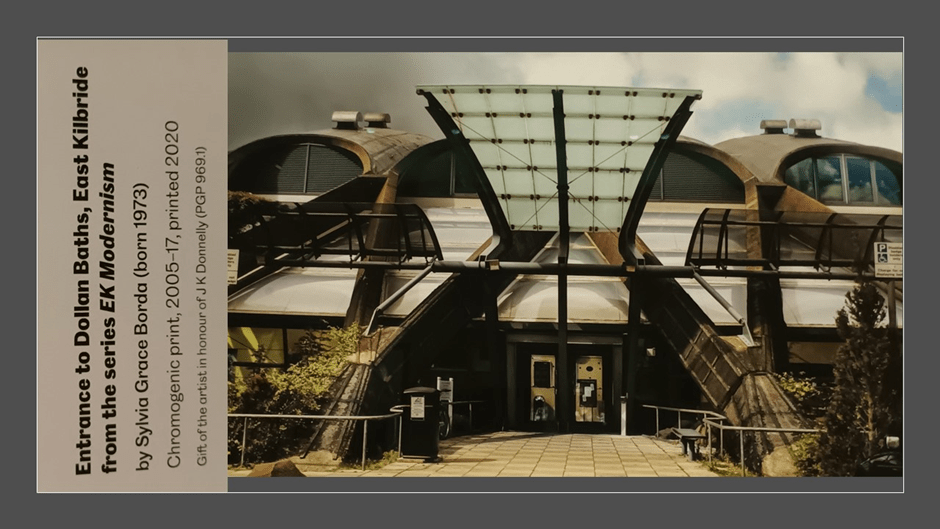

I did not know the work of Sylvia Grace Borda but there are tremendous works that tackle the subject of working class ‘schemes ’of housing as sensitively, if from a less dramatic historic moment. Below is her Westwood neighbourhood, East Kilbride. It so perfectly encapsulate the projects in terms once used of them – as warehousing, and here ‘garaging’ of the working class, only then to leave those public spaces in the domain of public neglect.

One insistence in this exhibition is that we fail to look at public architecture and neglect what is there to see. I think we can take that too far into an aestheticisation of misery, and hence Leslie’s insistence that is human process at times of transition that matters.

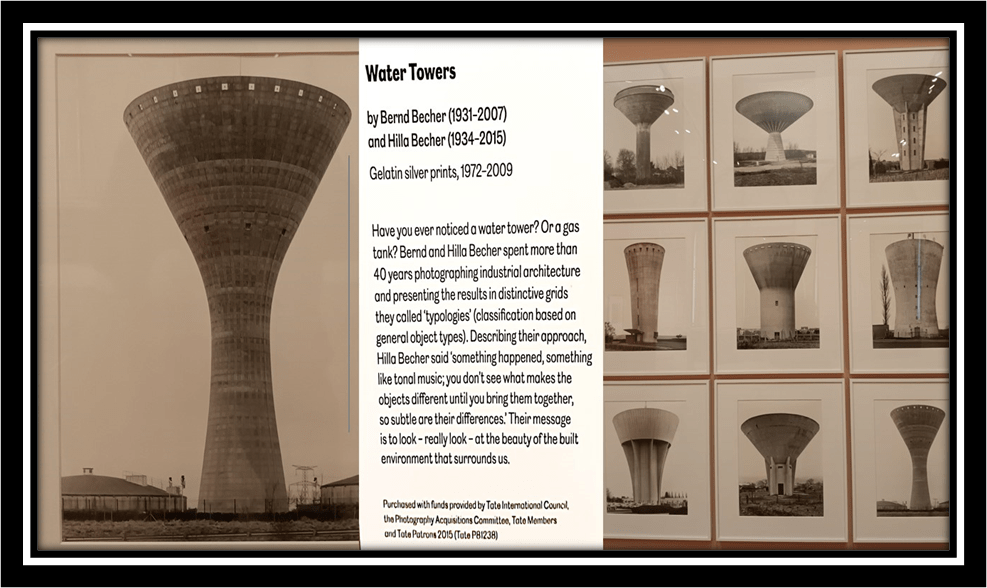

However the concern with public works had noble aspects whether from private or public finance and we would never be forgiven if we did not use the invitation to look again at examples of it. Water Towers are, of course, a case in point:

We are less likely to ignore concert halls, such as that commemorated by Sybil Andrews in 1929. But I would have loved some encouragement here to wonder why Andrews chose to record such architecture in a linocut print RATHER THAN a photograph of a project. Perhaps there is enough in the plaque. It has something to do with the way in which prints allow for chosen effects of tonal constraint and overlay,, such as I glanced at in Part 2 of this blog.

And modernist public architecture gets its place in the photograph. Strangely, we see the Dollan Baths by Borda in a kind of new light. Even the skies seem to dramatise though their temporality. It comes perhaps from a different time of public-private development of spaces, as this linked view of its history shows. It is now an Aqua Centre. Modernised as a hub of commodity leisure rather than public space.

Situated next to the Library, we see how here the exhibition does eventually suggest to us that it has an architectural concern, where the photograph merely records space inadequately (for flat reproduction can hardly measure up to what the architect says of its appeal in the flesh on the work’s plaque). Here I feel the focus of the exhibition dissipates a little.

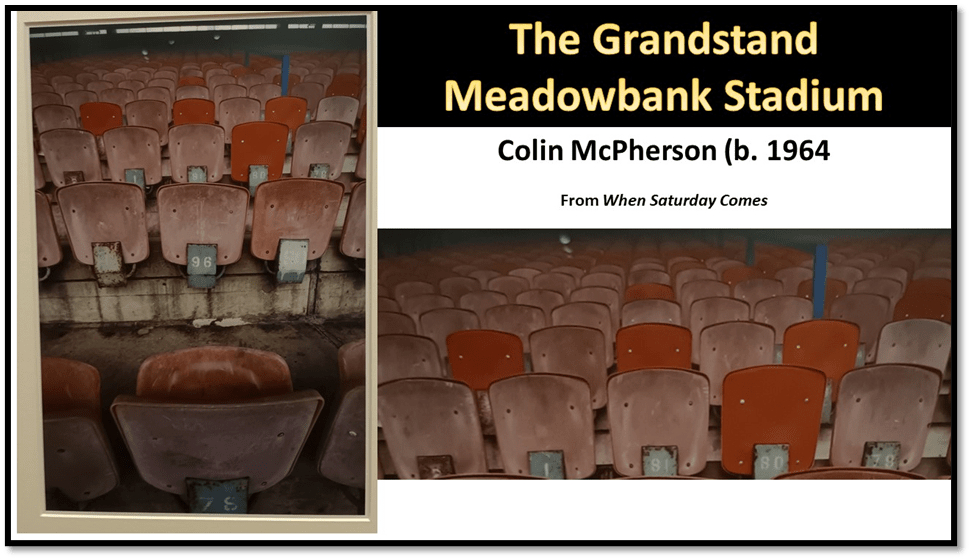

This is not the case though with the photograph I want to end consideration of the exhibition with: The grandstand, Meadow Bank Stadium by Colin McPherson. This is not a case of just being asked to notice what we have not noticed begore, as with the Water Towers previously mentioned. It is about the nature of social space, its use and wear in time and its organisation. The numbers on the seating becomes a feature of the photograph pregnant with meaning about the differentiation of individual and social memories in public architecture. Even the turned backs of its seats feel emotional. I just loved this piece.

I left the exhibition fully satisfied, if full of questions – not ones you can answer but ones that make looking more carefully at things in the world worthwhile.

There was still time before my train. The Printmaker’s Art catalogue had mentioned William Strang, so I thought I would hunt one out. No-one knew of them (there was his portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson but I discovered too late to take a look). So instead I chose to look up some favourite writer’s portraits. I had not known, for instance of John Burnside’s 2016 portrait by Alan J, Lawson, which does that wonderful writer proud. Here it is with a photo of some of my collection of his books:

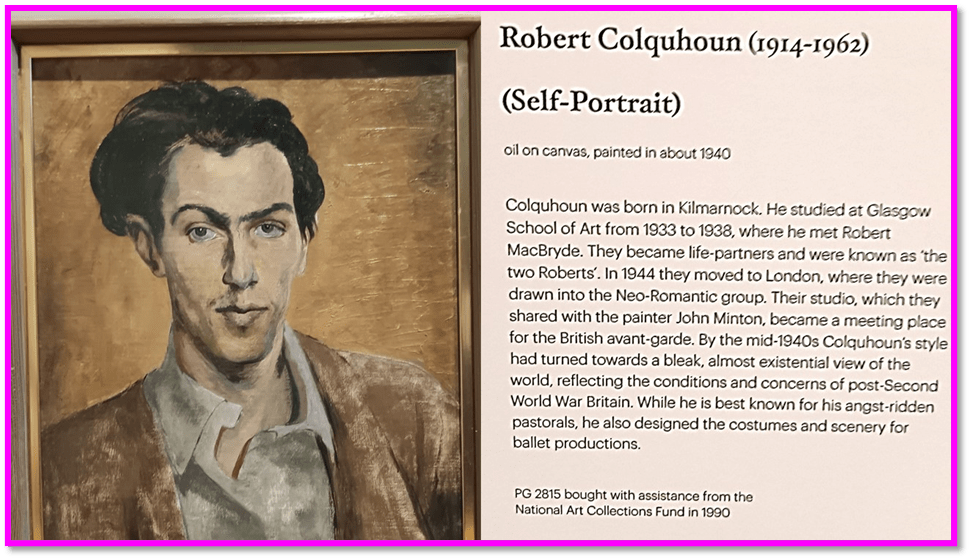

Having seen it I paid homage to some Scottish queer artists: Robert Colquhoun, whose biography on the wall plaque is rather coy about this bold liver of a queer life when it was much harder. I wanted to protest.

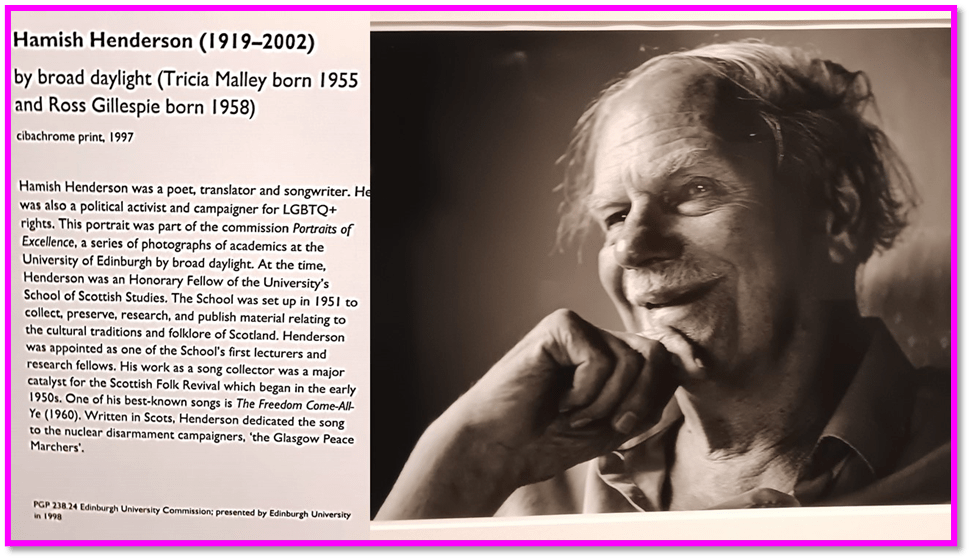

I was delighted thought to find a photograph of Hamish Henderson, to soon forgotten in England, whose work I love and first got to know through his translations of Antonio Gramsci, the only ones when I started reading him. His life, unlike Colquhoun and the other Robert (MacBryde) in the ‘Two Roberts’ as they were known. His poetry could have rivalled T.S. Eliot for his age and his support of LGBTQ+ rights came late, after a career in the history of folk-song, but that is hardly surprising. To read of his attraction to men (hardly even tried experimentally as far as we can see) is buried in expressions of memory and desire in his war poetry. But a man to honour. Love to you Hamish!

In veiled tears, I left for Waverley Station. It was a good day. A great day. I miss a comrade to feel these things with though. Started writing Part 1 of this blog on the packed train home where my Geoffrey was waiting at the station.

All my love

Steven xxxxx

Wonderful post 🌹

LikeLiked by 1 person