For Part 2: A day in Edinburgh with Prints and Photographs: (2) Hidden ingenuity and affordances to thought and meaning in the Art of Printmaking: use this link.

My train leaves Durham at 10.25, by the latest Trainline estimate, and Geoff is taking me to the station. I could not have chosen a worse day, it seems, for forecasted weather, but in Crook, there is as yet no sign of snow. And in fact, it turns out that the day in the train was caused by signal failure, not weather. I am delighted that I persevered with making this journey. It is not even that cold on the platform.

Why am I making this visit. First, I wanted to see the exhibition of prints at the National Gallery and to see the National Gallery again after its long closure. The gallery blurb makes much of the encouragement it gives yo visitors to govevthe art of printmaking a go themselves. I don’t think that, in my case, this is going to happen, and I will satisfy myself instead with a taste of the history of printmaking from Durer onwards. This is what it says I should expect.

Journey from Albrecht Dürer in the fifteenth century right through to contemporary artists like Tracey Emin and Chris Ofili. On the way discover how artists have pushed the boundaries in both subject and technique through screen printing, etching, engraving and more.

National Gallery Scotland webpage

Big names on show include Hokusai, Andy Warhol, Goya, Rembrandt, William Blake, Elizabeth Blackadder, Paula Rego, Bridget Riley and Pablo Picasso. See the techniques, tools and materials up close – you may even be inspired to give it a go.

I hope to see the exhibition, admire the gallery again, nuy the catalogue, and then, after lunch, go to the National Portrait Gallery for the novelty of a free exhibition with a photographic exhibition of how modern spaces are conceived. Here’s the blurb:

Architecture is a record of human life past, present, and future – we are all intrinsically linked to it. Making Space explores how architecture impacts people’s lives. A poor built environment exacerbates inequality, but architecture has the power to address social issues including homelessness, poverty, and displacement. It considers how the built environment has a significant role to play in creating a more sustainable future.

National Portrait Gallery webpage

Architecture has also been an enduring theme in the story of photography. Visually engaging and physically static, buildings were the perfect subjects for early photographic experiments. In around 1826, French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce made the first known photographic image – it was of the rooftops visible from his studio. Inspired by this and the wealth of incredible material in the national photography collection comes an exhibition which celebrates the connection between people and the spaces they exist in.

This free exhibition spans the breadth of the history of photography. …. Follow the line from Hill & Adamson’s early experiments on Edinburgh’s Calton Hill through to spectacular contemporary photographs by Andreas Gursky and Chris Leslie which capture the breath-taking scale of modern buildings.

I love Chris Leslie’s work, having a copy of his Making Glasgow pictures from which the birdman picture on the website derives. And the Portrait Gallerynotself is such a fine example of mock Venetian Gothic, very Ruskin. So so much for my delicious expectations. Lol. In every sense this exhibition then is tjevrelationship of space to images of social loving aimed atvyhr restoration of dignity for human beings. Of course, Ruskin’s experiment failed but at least he tried Unto This Last.

So, on the train now.

Next report. Arrival at Edinburgh. See you there. xxx. And, well, the train arrived almost on time. Edinburgh was positively balmy following the National panic about a frozen North today. Witness Prince’s Street after the exhibition.

The expedition too was stupendous. However, at home now and still not exhausted of the day, I do not want to complete here my account of that day as a whole because it was was too long and too productive to do other than introduce it here. In Part 2 (which will be tomorrow’s blog – the link will be added when both are complete), I will both say more about the themes of the exhibition and of the rest of the day. Suffice it to say it was a brilliant day.

However, let me introduce The Printmaker’s Art exhibition and its great catalogue which I read over lunch at The Mussel Inn on Rose Street over a dish of gambas in Moroccan butter sauce. As I expected, the catalogue, which has some works that varied from the actual exhibition, tended to focus on the invention of varied techniques of printing rather than the creative contribution of the art. Here it is on the table of The Mussel Inn.

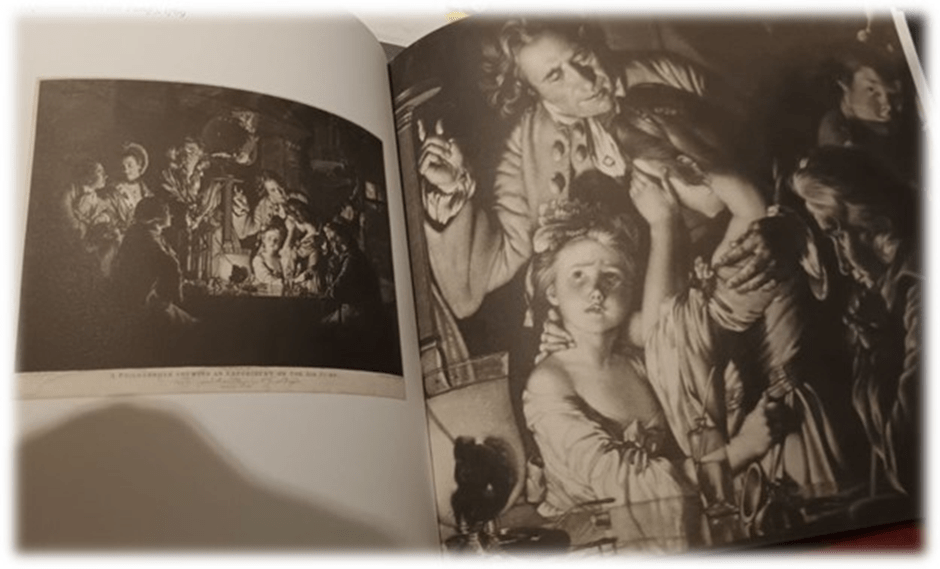

But after my last blog, I found myself (after reading this catalogue) retreating a bit from making that distinction between invention and creativity I pedalled there, for creativity in printing often goes hand in hand with the invention, adaptation or hybridization of processes in novel ways, such as mezzotint. Mezzotint, the catalogue shows refined on the creative effects of tonality, texture and volume that chiaroscuro effects in woodcut developed less fully. That isn’t the best example of this trend, for, in the catalogue, mezzotint examples tend to ‘improve, on chiaroscuro mainly for the purposes of realism of representation, especially the illusion of the volume of human flesh in social quantities rather for more deeply creative reasons. See for instance the opening of the book illustrating depth and volume effects using mezzotint reproduced in part below (pages 50-51). It shows Valentine Green’s’ reproduction of the imagery of human congregation found in The Air Pump, a painting by Joseph Wright of Derby. I did not see this print in the exhibition, but I don’t miss having done so particularly, impressive as it is.

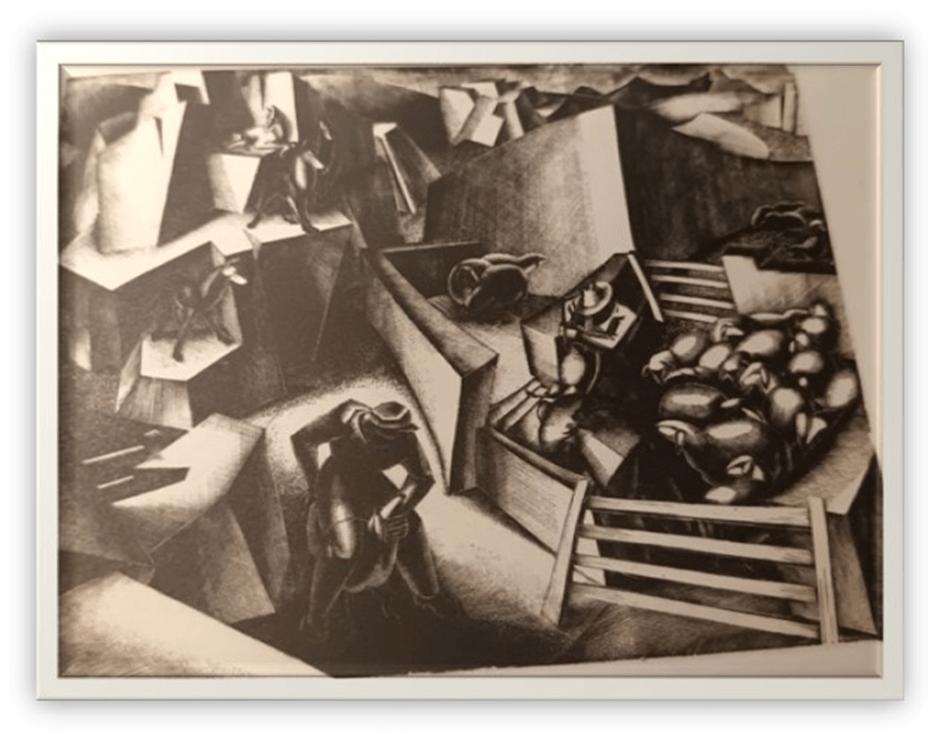

I did miss however seeing, from the catalogue examples, Agnes Miller Parker’s Sheep Dipping in Wales, for here is a woodcut, using traditional techniques of chiaroscuro for truly creative ends, and representing the very best of Vorticist conceptions of art. These conceptions re quite difficult to articulate and certainly not just a derivation of cubism as Parker’s mentor, William Roberts, always insisted. For in examples of true Vorticism, we don’t see only many perspectives on a thing (as is the case of the cubism of Picasso and Braque) but a spiralling of space in ways that seems to expand its range while maintaining a a sense of the claustrophobic containment of life-forms, human and animal:

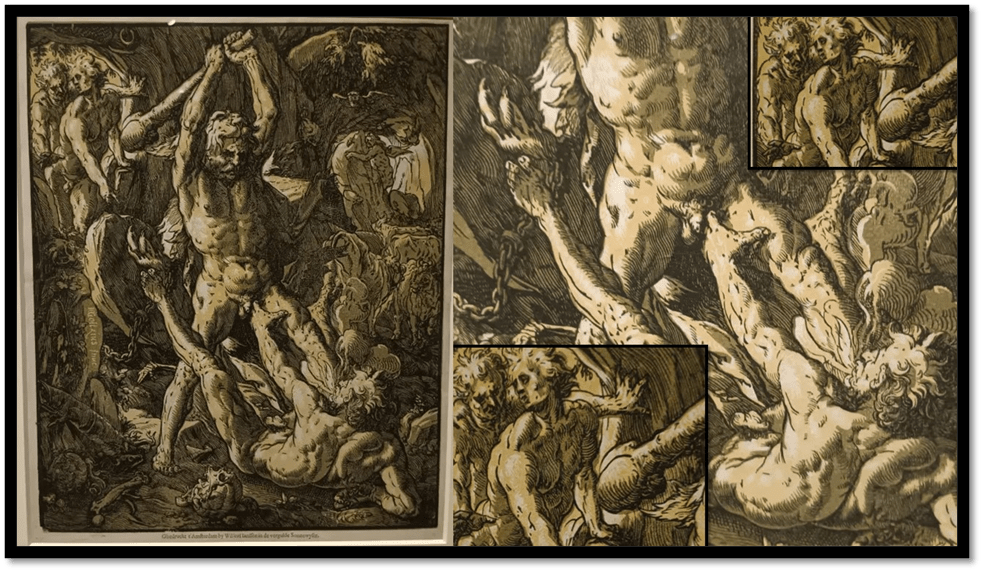

That I did not see the original of this print pains me a little. But that feeling is not uncomplicated for I saw some works that aren’t in the catalogue, such as this by Hendrick Geltzius’s fun work: a fine sixteenth century chiaroscuro woodcut, purportedly showing the conflict of Hercules and Cacus, a scene from The Aeneid, and, as the explanatory plaque says, ‘the triumph of Good over Evil’. But there seems also much in the creative finesse of the printing that creatively queer that contest, as Cacus, spreads has legs for the downward arrival of the hero’s huge club. In the background detail, there is much homoerotic suggestion. How to read all this? I do not know! However, it surely has to be more creatively and richly read than the plaque does, which emphasises mainly ‘dramatic three-dimensional effect’.

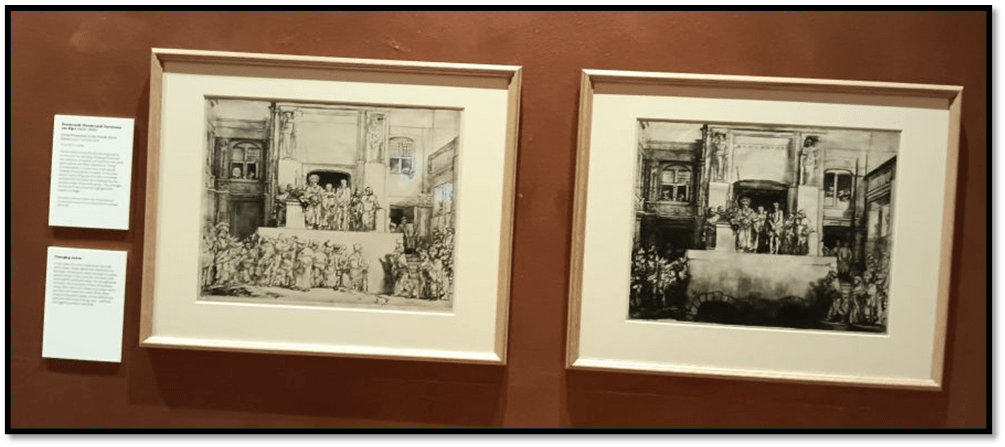

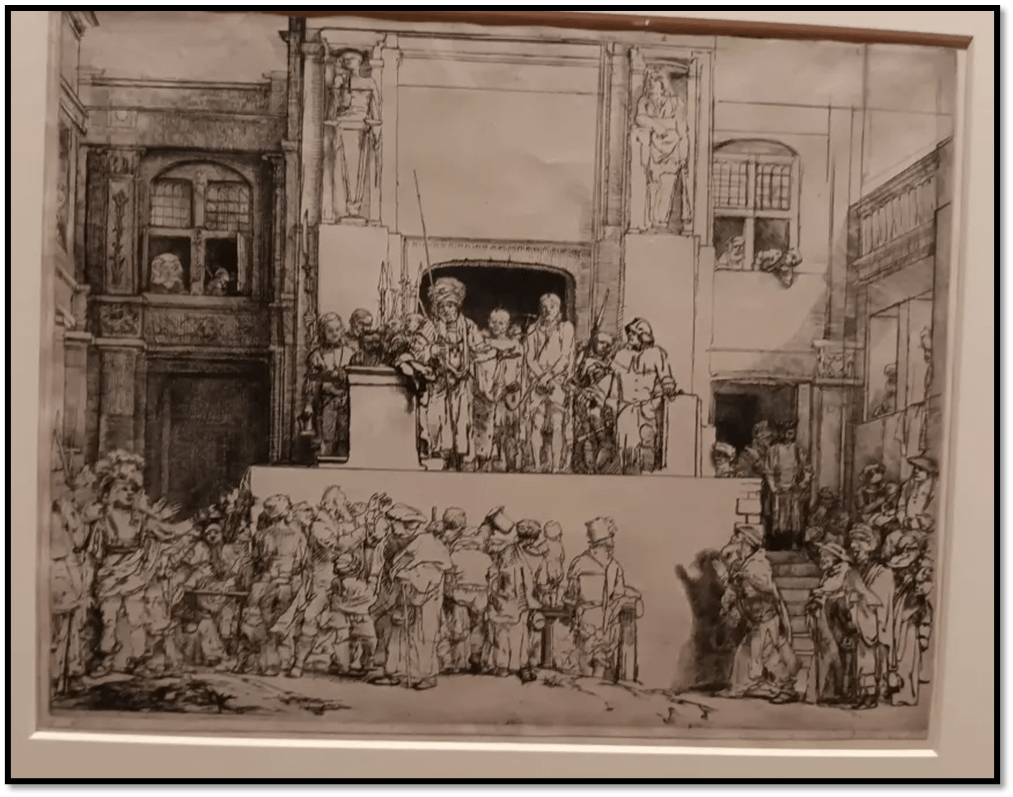

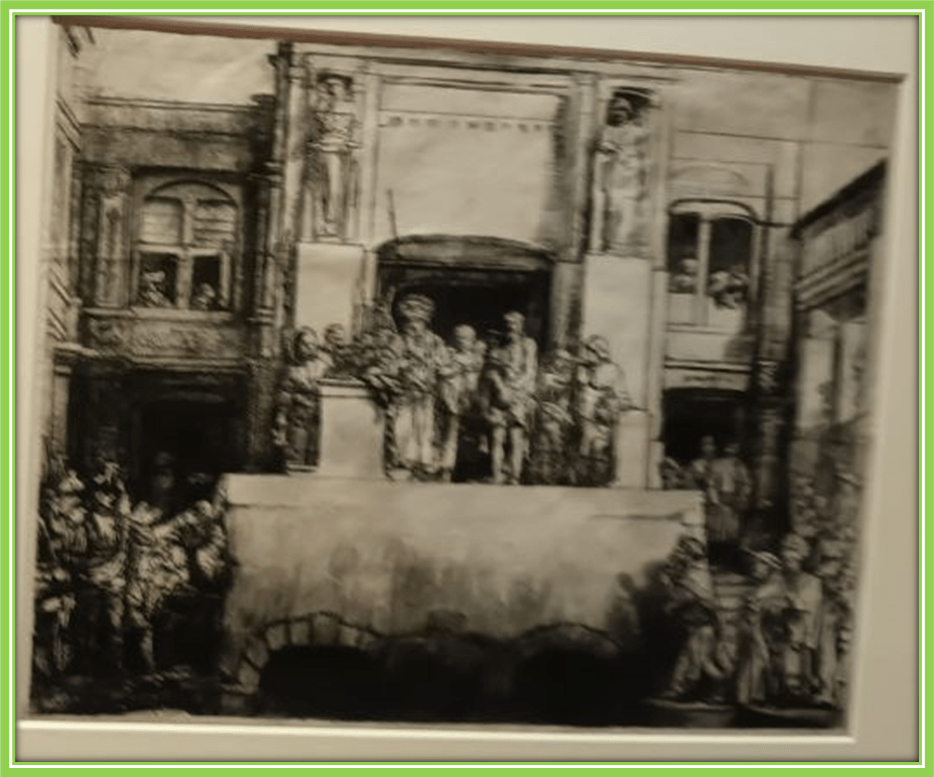

But a comparison of what I saw and did not see is a limiting way of indicating the variety of the exhibition itself, which I yet need to indicate and example in this introduction. The variety is not explicable by the method of printing or variety of methods, for many of the greatest examples (those from Rembrandt, for instance) are hybrid forms. The use of Rembrandt tells us something of the limits of the curatorial approach. The two versions of one print Christ presented to the People (Ecce Homo), which is not the example in the catalogue, below are ostensibly given to show how a great artist might exploit the fact that when printing blocks became over-used, they had to be recut. Rembrandt varied the treatment here immensely. The curator’s hence made the ‘changing states‘ in a particular print’ s career its main focus.

In my view, that is a pity, since the changing state is to me actually more interesting in that the conception Rembrandt has of his subject (a common theme in Christian art but never quite done like Rembrandt) entirely changed in ways that have as much to do with aesthetic and content-based decisions as the use of the opportunities offered by printing technology.

In the first state, the intention is, it seems, to represent not only Christ and the Jewish dignitaries around Pilate but also ‘ the people’, almost as a concept. Rembrandt does both by varying his subject between the great personages of the scene being presented on a stage and a lively and human varied congregation below it in a kind of auditorium.. The whole conception is delivered as a realistic drama, using architecture that his audience sees in finely drawn detail and that is contemporary to them rather than Jerusalem under Roman occupation.

In contrast in the second drawing, the auditorium has been cleared except for small groups at the stage sides. The blank wall of the front of the stage-like structure attracts our gaze largely because of its bold use of blanks and dark shadows (even the pentimento ghosts of the changed printing matrix). Personally. I think the inference is that it is the viewers of the work (us, as it were) now who, in part, form the ‘people’, to whom Christ is presented. It is this group that hence must take responsibility for disowning the Messiah, always a message of the Counter Reformation Church (though Rembrandt far from identified with that Church). Moreover, though architectural detail remains the scene is given over to tonal chiaroscuro effects, that predict the conflict of emotion of the scene itself, including the dark guilt of human responsibility for Christ’s denial and the being-given-up to Crucifixion. These decisions are not only cognitive and affective but also both genuine and holistic creative choices. They are not just playing with prods to inventive (or re-inventive) ingenuity given by the very range of print methodologies continually opening up to artists in the seventeenth century Holland.

In Part 2, I will, at the very least finish with this exhibition by illustrating its themes and the excitement of its range – far greater than anyone would expect.The series will continue with musings over lunch and a summary of great moments at the National Portrait Gallery. I hope you join me. But let me leave you on the steps of the National Portrait Gallery, having seen the exhibition I have yet to finish writing up and looking forward to the next.

It has been a tiring day. i think I will just watch The Apprentice now. Forgive me!

With great love

Steven xxxxxxxx

2 thoughts on “A day in Edinburgh with Prints and Photographs: Exhibitions in National Galleries of Scotland: (1) Introduction”