W.H. Auden, in his poem O Tell Me the truth About Love, mentions amongst his many happenstance encounters with people who claim to know, or ‘looked as if ‘ they ‘knew’ about it, and the passing written references in history to times when it appears it did not pass without effect: “…. ; / I’ve found the subject mentioned in / Accounts of suicides, / ….”. Did Auden have things to say about love that is tantamount to being the means of avoiding suicide, and even overlong despair? On finding a second-hand copy of the volume of 15 selected poems: W’H. Auden (1994, this paperback edition 1999) Tell Me the truth About Love: Fifteen poems by W.H Auden, London, Faber & Faber (available at this link). With some passing reference A Gobble Poem snatched from the notebooks of W.H. Auden & now believed to be in the Morgan Library (1967) London, F**k books unlimited (a poem of still uncertain attribution to Auden).

Richard Davenport-Hines in his 1995 biography gives a very early summary of Auden as a thinker about love that the biographer seems to think were a kind of limiting factor on his capacity to experience and maintain l love relationships all of his life. His ability to love might as well, he concludes be delivered to a machine as a person and was in his 1924 poem The Traction Engine:

Unfeeling, uncaring; imaginings

Mar not its future; no past sick memory clings.

Yet seems it well to deserve the love we reserve

For animate things.

This is not, Davenport-Hines tells us, because his affection for machines over-rode all else per se, but for the negative reason that they were ‘deaf and dumb, unresponsive, giving neither instruction nor criticism’; in brief, they made no demands on him nor claims of having feelings for him requiring reciprocation. In fact Davenport-Hines insists:

Auden’s love had to exceed everyone else’s bounds. His feelings had be unreciprocated, or at least impossible to match in strength. He did not respond at this time when he was the object of love.

Yet I wonder at the strength of evidence based on Auden as a sixteen-year-old schoolboy resisting physical expressions of their affections from older men, except as mentors, who wanted to him as a ‘Chatterton, on whom I would lavish all I could muster of literary maternalism’, as the journalist Michael Davidson said when introduced to Auden by his ‘homosexually inclined’ music mater, Walter Greatorex. Equally the fact that friendship with schoolboy peers tended to diminish any action based on the ‘erotic undercurrents’ in them and instead focused them on ‘romantic and grandiose’ professions of his love that he sustained briefly.[1] After all teenage boys, may well feel that the exercise of their feelings could be as much a prohibition on the overly pragmatic necessities involved in sexual satisfaction as any counter-feeling. For Auden was intensely ethically programmed as a child.

For me, the insistence of biographers on finding a non-contradictory and integrated sense of Auden’s position on love as he aged has little to offer us as readers of poetry, for it deals with matters that are shrouded by the contradictions experienced by queer men attempting to align themselves in discourses that alienate them or even exclude them: and ‘love’ is the subject par excellence to do that, maybe particularly for a highly intelligent and an otherwise entitled schoolboy. And the experience of a poem like O Tell Me the truth About Love is surely that of an open and puzzled question about those contradictions, tied up in in-jokes like that of the wife who disapproves of her husband’s willingness to acquaint the male narrator of the poem with what he ‘looked as if he knew about love’. We learn that she ‘got very cross indeed, / And said it wouldn’t do’. Yet that is a kind of learning however jokily conveyed that love in certain conditions (with another’s spouse or between two males) is considered transgressive. The patter of delight with which this is conveyed is the stuff of both contradiction and the release of libido Freud tell intrinsic to jokes.

And the rest of the poem employs rather random reductio ad absurdum comments or naïve questions about love, that render it on the edge of disturbing. Words evoke the contradictory ways that love might manifest itself as things other than itself but which are at least knowable directly. That hedges are ‘prickly’ and ‘eiderdown fluff’ soft does not exhaust the fact that soft and prickly, though very contradictory textures to imagine in love, may well be human postures under which it is concealed but nevertheless exists. Likewise the thought of it as a ‘howl’ or a ‘boom’ opens up quite fearful ideas of its power that are not all absorbed by the similes used to evoke these sounds that are also potentially discomforting states of mind. Even the suppressed metaphor of love as like a playful child (pulling faces and ambiguous on a swing it urged you to help it to use) evokes what is uncanny and hard to read (‘extraordinary faces’ and being ‘sick’) as much as a smile of pleasure. ‘Courteous or rough’, like has a kind of class aspect to it – like the rough not careful enough to stand on your toes in a public bus, or mothing political platitudes and possibly ‘vulgar’.

The inability to comprehend love simply is the reason for its invisibility in Brighton, the Thames at Maidenhead or’ underneath the bed’. The play with semi-sexual meanings here (why Maidenhead for instance and the memory of a child that ‘beds’ hide as much as they might show about their purpose ‘under’ their appearance). It is less easy to find a problematic reason for the poem’s ‘I’ to look in a ‘chicken-run’ for love by that only further obfuscates any clarity we may have about its meaning and potential to make us feel things, beyond what puzzles us about our desire, or need an answer It is not, I think, the poem of a person who only wants love of which he is in control but of someone unsure what it might mean to ‘alter my life altogether’. For love is alterity or otherness perhaps, a sensation, feeling, thought or action hitherto difficult to comprehend whole. As the extension to the Miriam-Webster definition shows, ‘alterity’ and the verb ‘to alter’ (or change) are cognate terms:

Both words descend from the Latin word alter, meaning “other (of two).” That Latin alter, in turn, comes from a prehistoric Indo-European word that is also an ancestor of our “alien.” “Alterity” has been used in English as a fancy word for “otherness” (“the state of being other”) since at least 1642. It remains less common than “otherness” and tends to turn up most often in the context of literary theory or cultural studies.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/alterity

And at the poem’s nub is this, that I use in my title: “: “…. ; / I’ve found the subject mentioned in / Accounts of suicides, / ….”. The puzzled silliness of the narrator here may feel initially as absurd as his penchant for reading the scribble on the ‘back of railway-guides’ but it is a moment (in fact they both are – both evoking persons in a moment of transition and change puzzled about what ‘love’ has to do with that alterity. Far from the coldness one feels in Davenport-Hines Auden, I sense a man never able to really come to terms with normative versions of ‘love’ and continually finding them confused with other things, which may or may not be different from it, such as sex and community of purpose, whether in dyads or larger groups (the concern of many of his plays). But the alterity found by the suicide is not a happy one after all – and these ‘accounts of suicide’ (even in the coldness of word ‘accounts’ with its suggestion of balancing numbers in an ‘account-book’) are a disturbance in the cheerful water of this funny poem.

Love in particular becomes hard to understand in its coupling with ideas of what lasts and is durable, a puzzle that must have struck Auden as he contemplated the brevity of both his own affection and others in relationships, as well as their even more puzzling longer durations. For a poem he knew and loved had said already that though love may alter you, love is in itself is the very opposite of ‘alterity’, a constancy in the fixation of the object, though even that poems final couplet casts love into doubt with the fear that ‘no man ever loved’:

…; love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

O no, it is an ever-fixèd mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

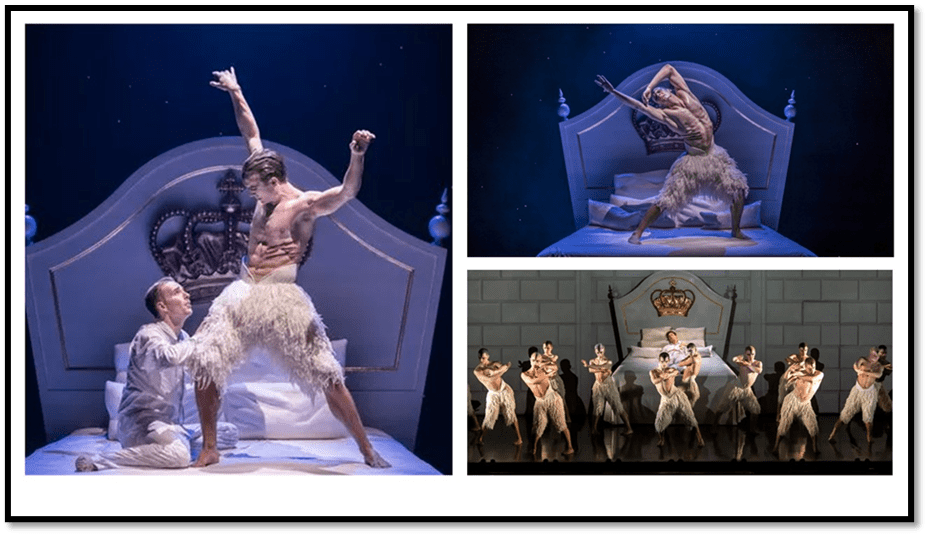

That such love is fanciful is I think the ironic twist in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116, ‘Let me not to the marriage of true minds’, a poem set in a narrative of a sonnet sequence where everything alters and changes many times – from the love of a ‘fair youth’ to a ‘dark lady’, from love of a man to a woman just as seasons change in it and in time leaseholds end their term and monasteries fall into ‘bare ruin’d choirs’. It is there in the ambiguity of a ‘swan’ in Auden’s beautiful ‘Song’, which surely refers to ‘Swan Lake’ wherein the White Swan is perfection in love object choice and the Black Swan is perfidious and false (and all that meant in Tchaikovsky’s life) and undermines that fanciful notion of the constancy and temporal endurance of love: ‘white perfection’ stands because it is consonant with doing the act of love and being gone “Upon Time’s toppling wave”. Indeed this is not unlike the way Matthew Bourne’s production undermined the back-white binary. The white swan is praised most when it gives ‘voluntary love’.

No poem instantiates this better than that one which runs through my head whenever love strikes it Lullaby, in the imagination, for instance, of inviting the loved one’s head (that most usually restless of bodily organs) to lay on you voluntarily and without promises – for this is a ‘faithless’ arm, with all that word might mean (fickle, disloyal, unbelieving or treacherous). For me the issue here has always been that which emergently defines the ‘Human’ in the poem, as that which cannot sustain duration – arms ache soon following the laying on of weight – but is not therefore necessarily without what we might call ‘true love’ embodied in its offer to another.

And here is the answer to suicide as caused by the breakdown or end of a love match, or even something that may have passed as one in as far as it was not in the end at all definable as MUTUAL between partners. Hence the address in this poem, which is truly sympathetic to the ‘grave’ vision of Venus ‘Of supernatural sympathy, / Universal love and hope’ whilst aware it may not in the true measure of the meaning of human lives be any more worthy than the ‘hermit’s carnal ecstasy’ (and the apotheosis in that phrase of what might be called a ‘quick w**k’). For if we ‘Let the living creature lie’, in our professions of either offering or accepting the fully embodied love of alterity, then we have to recognise that it is time-limited: and that what is ‘entirely beautiful’ like a white (or a black) swan.

What Auden insists on, I would say, is that the attempt to call love ‘timeless’ and ‘eternal’ is precisely at the root of those ‘accounts of suicide’, which paradoxically are stories (at least if provoked by rejection like that at the end of James Joyce’s story The Dubliners) of people who kill themselves because they cannot accept the need to, as Auden puts it: ‘Find our mortal world enough’. In a poem that accepts that time passes in the same way that faith does (the problem Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach struggles with):

Certainty, fidelity

On the stroke of midnight pass

Like vibrations of a bell

…

Never has faithlessness been better sung as a reality that we either struggle to understand as cognate with love or fail to do so and become the subject of not only suicide through what we interpret as ‘rejection’ alone (for it is that but that is not its meaning in total) but from being unable to face the end of certainties in religious or other constructions of ‘faith’ and ‘certainty’ (even the certainties of positivist science for these too are delusory). The hard lines of this poem are:

Nights of insult let you pass

Watched by every human love.

Here’s my reading. The key ambiguity in it is in the understanding the grammar of the first line I quote is the. Are we imagining the subject of the verb ‘pass’ as ‘Nights of Insult’ or ‘you’. Are these nights when I break respect for a supposed fidelity in love and ‘insult you by letting you ‘pass from my mind’? Alternatively, am I imagining ‘you’ passing nights that ‘insult’ my demands on you because of your infidelity. In truth, these readings are both there, for each and every such ‘night of insult’ is none such when watched from the vantage point of ‘every human love’, which is necessarily multiple and uncertain in genesis or end.

I love this difficult poem but not because I am mature in its teaching but because it promises such a maturity to be possible through the weight of our own guilt at being ‘fickle’ or difficulty in accepting the otherness of a loved person from yourself, both very toxic things, And in the end the problem is demands of certainty about self, other, the human community or God. That is the deeper meaning of Shakespeare’s Othello, which demands in several of its characters a world entirely knowable that does not exist, nor ever will.

The odd thing however that though Auden felt suicide an unsupportable sin and scoffed at those who exhibited personal pain in poetry, especially in his older age when he actually heckled Anne Sexton for reading a poem at an International School on her ‘attempted suicide’ and was so rude to her afterwards that ‘he reduced her to tears’, he never learned the lessons himself I claim he taught in the love poems I have looked at from the 1030s.[2] Hannah Arendt was claimed by Frederick Prokosch to have said of him to ease Prokosch’s feelings of having been rejected by Auden:

Wystan is hideously entangled and yet he longs for simple certainties. He feasts on all the varieties of unreciprocated love, or call it, if you wish, unreciprocable love, and he ends by growing ever more dissolute and alcoholic as simultaneously he grows more didactic and avuncular. …[3]

Out of this grew poems like The Platonic Blow (published without permission by Fuck You magazine) which I have in its English pirate as The Gobble Poem (see collage) but Davenport-Hines tells us he told Nevil Coghill that the poem’s treatment as pornography by ‘Hippies’ (whom he admired enormously as reviving ‘the spirit of Carnival’) saw in it only formlessness, which he detested, as a result. What they should have seen is its patterns of reference to high art and higher thinking (as a portrait of a ‘day of insult’ to love) because ‘in depressed moods I feel it is the only poem by me which’ they have read.[4] And the poem too is about the delight of patterned sound not just the coy thrills of the body: hence its ‘rhythmical lunge’, and patterns of internal rhyme and assonance (so much more delightful than end-rhymes which it has too).

But that is problem about uncertainty and infidelity: if you can’t bear the heat you get out of the kitchen. It is unconscionable how horrible Auden was to Anne Sexton because her life had no certainties at all.

All I have to say today

With love (but no certainty or fidelity)

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Richard Davenport-Hines (1995: 45ff.) Auden London, Heinemann.

[2] Davenport-Hines op.cit: 327f.

[3] Cited ibid: 326

[4] Ibid: 328