‘beyond the light of memory / behind your life / there might be / other lives, waiting – ‘, ‘… I could have spent / a thousand lives changing myself,’. Queerness, allusion, metaphor and metamorphosis in Seán Hewitt (2024) Rapture’s Road London, Cape Poetry.

I have waited a long time for the publication of this volume, for I love the prose and poetry of poet, translator, scholar and memoirist, Seán Hewitt, but having read this new volume I am cautious for I often get him wrong when it comes to lyric expression, as I think he once told me in a public place (I don’t know him personally by the way, just follow his career and honour his queer heroism). In a tweet, I think I remember him praising a review of Rapture’s Road, as doing precisely what critique of poetry, as poetry, and not a statement or coded message, ought to be. It’s a very short review so why not quote it in full. It’s by Oluwaseun Olayiwola in The Guardian’s ‘Best Recent Poetry Roundup’:

“He likes it, he likes me / when I break. It gives him something / to assemble” admits the opening poem Ministry, in which two lakeside lovers tessellate themselves into the “bone-hard and lucent” landscape, as if their lovemaking were its own biome: “When I break, / I break, predictably, into song”. Hewitt’s speakers are music-mad: his world is replete with “air-quiet lullabies”, “the high black notes of starling flocks”, and “the soundproofed room of heaven”, a masterfully compressed abstraction that would seem to problematise the rich history of gay lyricism in Judeo-Christian systems of belief. But Hewitt’s words indubitably penetrate, with Nerudian passion and force: “I made for him a word / Adam could not have said inside the garden”. At the core of these unflinchingly sonorous lyrics are prose poems of tethering and untethering to a lover: “I needed to live whole within my longing, punished you for your kind, unknowing love.”[1]

Indeed reading that again, it is difficult to know how to improve on such percipient brevity that places Hewitt’ where he ought to be in the vanguard of a modern renaissance of queer lyricism that speaks of love, whilst regarding the body and its interactions with thought, feeling and action in the process. However, I do flinch at calling his ‘passion’ Nerudian, for that ties down too neatly a complex configuration of liturgical ritual (it’s a Ministry after all) and Dionysiac disorder and loss of all sense of what Judaeo-Christian culture has compounded, in collusion with the history of patriarchal capitalism since the sixteenth century at least. It is indeed a religion based ambiguous love and hatred embodied in the lonely voice of the psalmist and priest, witnessing to the highest ideal it knows; an ideal so limited in other singers than Hewitt I think. Hewitt’s poetry is not precisely Nerudian any more than it is the product of any other writer that it references or cites, notably Ovid. For this is a poetry of Metamorphosis.

It is so in its very visceral substance, like those internal organs ‘heaved out’ from an Irish family’s pig on the event of its slaughter by the family that raised it. That substance transforms in his priestly hands into:

The folded luxurious

Parachute of her innards –

It felt almost like love

…[2]

For Ovid, is so visceral too, the flaying of Marsyas opening out into the imagery of bodies whose search for pleasure, orgasm (Hewitt has joked that these poems might be entitled ‘The Second Coming’) or stimulation (sometimes as in the case of the youth who ‘DIDN’T MEAN TO KILL MR. FLYNN’ perverted) apes the imagery of sickness and sado-masochistic violence that these poems explore oftentimes. Try these snippets, for they are only the less hidden ones: ‘mouths / discharging’, ‘emptying / the animal of his body’, ‘branches / flaying and whipping’, ‘turn / the body against / its own tenderness / and violate it’, ‘knives in the night – … thwack of bone on bone … splinters … fractured’ , ‘the musk / of those hot glands, / the stain of urine smeared … // and taste in it / a memory of violence, / its urgent expenditure’, ‘burn and brand me –‘, ‘sweet, / prying hands heaving the flesh // apart’, ‘I wanted to touch the wound – / there was a heaven behind it’ (in a poem where the word ‘tear’ plies between its different soundings and meanings so that they become cognate).[3] One would call such imagery that of medieval torture, had not the homophobic murder of Declan Flynn taken part in Fairview Park, Dublin, in 1982 and been condoned by the then priest-ridden Irish court system.

And then there is that poem about sado-masochistic sex itself, wherein the lyric voice becomes metamorphosed (becoming what it ‘turns to’) and who, as a heavily-scented (as it is) stock flower becomes passive to being read. Readers do so mangle the body of the poet’s work (I am one of the worst) like a ‘map’ and play about with it and hold it by the throat to ensure his ‘Split lip, ache of the windpipe’. Perhaps readers are sadists that JUST TAKE AND TAKE when ‘I gave myself’ as the lyric voice says, forcing the lyric voice to wear ‘his collar, / a trap, a metal-halo’. As one who reads sometimes like that I know the full force of Hewitt’s words singing to his ‘reader to /come and fall with me’, where fall has the full Catholic force, if for a different purpose, of the FALL of Humankind poetry when that poet ‘made for him a word / Adam could not have said inside the garden’. He couldn’t have said it then because he was THEN unfallen.[4]

Of course as a reader I must not feel guilty for my ponderous version of avid love for Hewitt, for the lyric voice here, after all is that of Ovid’s Orpheus, dismembered by his own followers – but so it is with lyric poets. He is I think, in a stunning reference to the Orpheus flower (if it is) ‘the garden’ that is ‘like a god / with a flowering mouth – ‘.[5] And, of course, poems do not contain ‘real’ violence, do they?. It is ‘only language’, people say who have never been cut up by it, as most queer people have – though not alone think of the sin of racism and everything looks small – with the force that metaphoric and metonymic usage gives it. Hewitt is in the front of the queue in knowing this, for poetry is, he secretly insists (even before Ovid in the threnody and dithyrambs of the most Ancient Greeks we know of the Archaic period and that became the function of choric verse in Greek drama) an insistence that verse can relive memorially of the whole of creation and destruction, and then antiphonal reparation enshrined as human life by the Gods We know he knows this because the beautiful lyric ‘And, so small singer in the flood, …’, ostensibly about a bird (a dipper) references reparation in the word ‘antiphon’, taken straight from choric Greek dramatic form and used in Christian ritual since the Greek Byzantines.[6]

We know it too because he tells us so in ‘A Strain of the Earth’s Sweet Being’, wherein Hewitt makes the mimicry of ‘song’ a means of embodying in words both sexual foreplay, afterplay (even the scenting of sheets in which your lover has lain) and play violence by burning or shedding and hanging as trophies the body’s fluids just by knowing the power of holding people as language in your sweet poet’s ‘mouth like a phoneme’. A poet knows what being positioned as ‘a locked noun tonight’ feels like, and desiring instead to do and be in free exploration of bodily sex, as a VERB: ‘Come out, make a verb of me, let / my body do your speaking tonight – ‘. [7] Of course, people forget that the voice is as embodied as the sexual organs and viscera and that poetry at root is so too, at least in lyric, fully ORAL as Hewitt, at least, celebrates it.

To tell truth, the only quibble I have with Olayiwola is not because I feel Ovid as important as Neruda in the seething chaos from which this felt poetry is generated but because I find this poetry so extensively allusive that those allusions to other songs and singers, human and animal, are also deeply elusive: you see them and then they are gone and indeed may never have been there. For instance Night Ballad thrills me in part because to my mind it comments on and queers Browning’s strange lyrics Meeting At Night and Parting at Morning. Yet I seem to reminder asking Hewitt at a book festival about Browning, whom I think he said he did not favour as a poet. What is clear though are citations from The Psalms (one at the least), Gerard Manley Hopkins – Hewitt’s Victorian and Catholic buffer example of willful refusal of the queer that inhabits him, his priestly role (the Ministry of the opening poem) and his poetry – my tickled and frivolous fancy is (do tell Seán) that the poem Pleated Inkcaps plays with Hopkins’ theory of ‘inscape’ and ‘instress’). Moreover, there is the luscious poetry of the aristocratic estate and notably the deer hunt (note the lovely prose-poem with its ‘sprung rhythms’ ‘The sleeping grass’ with its ‘fallow deer’ and a doe’, in the imagery of Elizabethan lyricists, especially Thomas Wyatt and his lesser shadow Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey.[8] Let’s take the last ones first, for these fascinated me and I invoked them in a rather insane recent blog (use the link to read) .

Howard provides the epigram to Part V of the volume: ‘The hart hath hung his old head on the pale’. Here is the sonnet in full in the original spelling, often called Description of Spring:

The soote season, that bud and bloom forth brings

With green hath clad the hill and eke the vale;

The nightingale with feathers new she sings;

And turtle to her make hath told her tale.

Summer is come, for every spray now springs;

The hart hath hung his old head on the pale;

The buck in brake his winter coat he flings;

The fishes flete with new repairèd scale;

The adder all her slough away she slings;

The swift swalllow pursueth the flies small;

The busy bee her honey now she mings;

Winter is worn that was the flowers’ bale.

And thus I see among these pleasant things

Each care decays, and yet my sorrow springs.

The hart’s head presumably lays reference to the shedding of its antlers by the mature red male deer, which recalls the hanging up of a stag’s head in aristocratic halls. It is a rich reference to life, death and seasonal metamorphosis then, which this lyric plays with in a way, despites its wonderfully ‘conceited’ (in the Elizabethan sense) imagery, in a very conventional way – the season is glad / lovelorn ‘I’ is sad (wow! there’s a Stevie couplet!). It is a stock heteronormative love poem that barely touches the sides of the potential of metamorphosis in queer love. A less conventional poem – indeed a very great one is however referenced in the title of a three part poem by Hewitt, ‘Whoso List to Hunt’. The poem it references follows:

Whoso list to hunt, I know where is an hind,

But as for me, hélas, I may no more.

The vain travail hath wearied me so sore,

I am of them that farthest cometh behind.

Yet may I by no means my wearied mind

Draw from the deer, but as she fleeth afore

Fainting I follow. I leave off therefore,

Sithens in a net I seek to hold the wind.

Who list her hunt, I put him out of doubt,

As well as I may spend his time in vain.

And graven with diamonds in letters plain

There is written, her fair neck round about:

Noli me tangere, for Caesar’s I am,

And wild for to hold, though I seem tame.

This poem to a powerful untouchable female is more than impressive, as is the picture of male vulnerability and impotence it paints, so unlike Howard’s conventionalities. And it is the queering of masculinity and male sex/gender stereotypes that Hewitt’s poem addresses: ‘the air sword-fighting / with itself’ reminding me strongly of Philip Guston’s paintings of the gladiatorial hubris of young boys, young men and even older men, dressed to kill like his Klu Klux Klan ‘ hoodies’ (see my blog on Guston if you wish at this link).

In his visit to a park where male cruising takes place (Hewitt’s poetry is stuffed with these) he piles into ‘the steam of their bodies’, bodies that are compared to ‘the young deer rutting’.[9] In the second lyric an Orphic embrace of nature and gravestones (life and death of course) suggests the fellatio often invoked in Tongues of Fire:

Among the broken

Stems of yellow archangel

I knelt to – … //

the streaked red tongues –

their little pietàs of pollen

dashed on the soil like the ends

of my wanting, …

Of course ‘yellow archangel’ is a wild flower found in such venues, just as ‘pollen’ is the product of ‘male’ flower fertility, though here suitably androgenised in reference to Marian pietàs and the blend of hot and hard sexual urgency and ‘all the soft parts blood powers / through’. In this lyric the lyric ‘I’ has fulfilled the secret longing ‘to shake of safehold’ of convention and heteronormativity.[10]

The final lyric is the greatest homage to Wyatt’s rhythmic urgency, where again male deer shed their ‘head’ (the ‘snapped antler’) which becomes the most graphic image of sexual ejaculation and ‘wanderer’s / copulating’, covered gracefully by the action of floral nature:

…, the blown prostate

Of a chestnut shell, yellowed

In the action of feral nature, stag’s throats ‘bulge’ and fingers work an ‘urgent expenditure’, using the conceit on sexual spending so beloved of Elizabethans, and more so by John Donne.[11] This is poetry of a very high order that scoffs at only ‘seven types of ambiguity’ (Seven Types of Ambiguity – Wikipedia), for ambiguities are in fact queer multiplicities and diversities in this heroic poet of our community.

I call him heroic partly for that is his emblem (‘regal, speared, violent’) in a poem which celebrates the pairing of ‘two men in latex’.[12] This is a poetry that does not balk from shocking sensitivities that are reducible in the end to fragile normativities. The main attack is on the notion of the unified self – rigid in its hardness (especially in toxic masculinities) – and often quite literally poisonous too. There are two other sly allusions to other poets and poetic traditions to show this. I love, for instance, the poem Sleepwalk. It is the only one that quotes directly as far as I know, from the Psalms. In fact it cites this (Psalm 88: 18):

In Sleepwalk, a whole world of masculinised endeavour is evoked in the first stanza. I suspect that Hewitt chooses the New Zealand hybrid dog but now a breed favoured as a working dog by farmers, ‘huntaways’, to stress its proximity to hunting references throughout the book, but also to indicate that kind of independent and secret searching for sexual gratification of many of the men in this and earlier collections, and his memoir, All Down Darkness Wide (see my blog on this at this link). Towers get built in this stanza and landscapes rearranged. Yet much of the rest of the poem does not honour this kind of masculine hardness of purpose and violence to nature.

A huntaway

Instead it stresses softness (after the gate has clanked at least) and a kind of non-presence, that of the liminal ( the ‘touch of rosehips’, ‘ghosts’, the ‘lovely, monastic’ and the feel of mist). In such an early poem the feels are mixed with fear and nausea perhaps, and this is why Psalm 88 is appropriate here with its paranoid fear of rejection by others: that psalm is the Psalmody of the male looking for the affirmation of his right to be adored and definitely not REJECTED. But think again about the phrase ‘cast / mine acquaintance into dark’. The phrase may have fearful neurotic meaning projected onto it by its Davidian associations of the soul feeling cut off from God’ but it also just states a soft fact. The men who sleepwalk into the disembodied poet’s searching are by necessity in the ‘dark’ quite literally and it need not be a fearful darkness but a soft and warm one with ‘catkins hanging / silver’.[13] This is what I mean by allusive and elusive poetry. The allusion does not render the meaning as it was long thought, in reading T.S. Eliot’s ‘Notes to the Wasteland’ for instance, it should in’ clever poetry’.

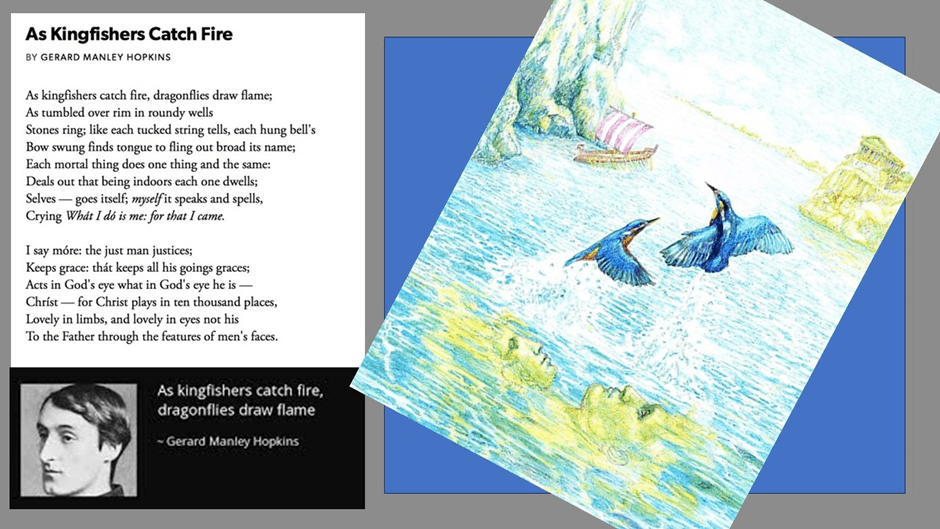

Likewise the sly allusion to Hopkins famous ‘When kingfishers catch fire’ in the poem Alcyone, which returns the poem to its Ovidian metamorphic roots in the transformation that created the ‘halcyon bird’, that of Ceyx, drowned at sea, and his widow ‘Alcyone’. The context of Hopkin’s poem is only nearly there – in the ‘superior light’ for instance – but rather metamorphosed like Alcyone herself, for she is also the poet’s mother morning her own dead husband, but that (and its almost the Hopkins poem opening) that ‘the sweet / water burned at its touch’ – a kingfisher has caught fire though the healing is minimal, for son and mother mourning. But it is not the neuroticism of the Hopkin’s poem ending:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying What I dó is me: for that I came.

It’s all ‘myself’ this lyrical sonnet, isn’t it? It’s all self-justification however dressed up in a theory of inscape informing the outward appearance: ‘deals out that being indoors each one dwells’, with instress on ‘do’.

And let’s pursue this queering of masculinity further, looking for the hind (the female deer in Wyatt) behind the Earl of Surrey’s ‘hart’ and ‘buck’ (the lads at animal play). For all the masculine bravado of some of the imagery (remember again that emblem (‘regal, speared, violent’) in a poem which celebrates the pairing of ‘two men in latex’, I already cited above.[14] Much in this volume is about exploring a range of fluid sex/gender self-assertions, actions, feelings and thoughts. When the lyric ‘I’ takes on nature for instance and flowers in particular it assumes it as a ‘dress’ decidedly feminine in association, soft and sometimes gaudy as befits a ‘flame-stitched boy’.[15] Twice the lyric persona is ungendered, even by this word being used literally. On the first occasion it is because of the soft and flowing feel of the ‘gown’ he steps inside in walking with the wind:

…, feel its folds.

The seam of it rippling its corpse-silk

Blowing and warm. Feel the fabric

Of the air loosen, liquid threads, feel them

Snap and hem and hood me, captive

In battens of air. Ungenders

The shape of me – sweet seamstress

Lightens the muscle of me, …[16]

It has never felt so wonderful to be unmanned. Except here, where fluidity experienced in the male-female binary as the ‘I’ of the poem ‘sank myself into the breast of the water’, such that : ‘I felt ungendered in its arms’. But far from being about just that binary or all of those ’I’ swims in many more new multiplicities.

… The soul I knew,

Was all plural. I could have spent

A thousand lives changing myself.

Dipping my body over and over

In those bracing, fluent desires –[17]

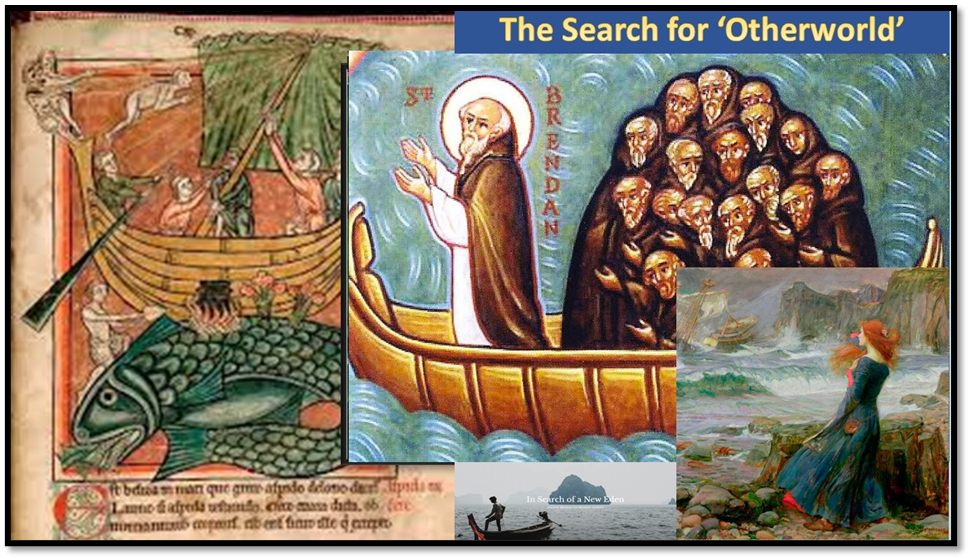

Metamorphic, allusive and elusive (and perhaps illusive in a positive way) this poem is called Immram. In Section V, Hewitt explores the search for alternative being (queer being) in this poem. It is one celebratory of the Ancient Irish poetic form of the Immrama (singular Immram), a literature that seeks ‘otherworld’ (Christian but based on an original non-Christian literary form – the Echtrai) and runs through modern children’s literatures, in C.S. Lewis, for example.[18]

In this poem, I do not cross water as in the traditional Immram, for this ‘was not a dream’. No: ‘I was being married / with the water’. It dare even invoke frankincense and myrrh as if the Christ child were present in the moment a child of ‘twelve’ enters sexual maturity in the presence of other things ‘blossoming’ like his newly released seed being ‘spent’.

Cape Poetry describe the whole work thus (I do not know if the words are Hewitt’s):

As the mind wanders and becomes spectral, these poems forge their own unique path through the landscape. This is a haunted journey through love, loss and estrangement. As the mind wanders and becomes spectral, these poems forge their own unique path through the landscape. The road Hewitt takes us on is a sleepwalk through the nightwoods, a dream-state where nature is by turns regenerated and broken, and where the split self of the speaker is interrupted by a series of ghosts, memories and encounters.

Following the reciprocal relationship between queer sexuality and the natural world that he explored in Tongues of Fire, the poet conjures us here into a trance: a deep delirium of hypnotic, hectic rapture where everything is called into question, until a union is finally achieved – a union in nature, with nature.

A threnody for what is lost, a dance through apocalypse and rebirth, Rapture’s Road draws us through what is hidden, secret, often forbidden, to a state of ecstasy. It leads into the humid night, through lethal love and grief, and glimpses, at the end of the journey, a place of tenderness and re-awakening.

I like this but it allusive and elusive in a different way: it refuses to name the shock to the merely conventional thinker and feeler the poems also must evoke. It is too easy to read what is there as ‘poet-speak’ mysticism, rather than about the discovery of the queer body, which it is as well, though it is also a condemnation of the industrialisation and destruction of nature by burning, pollution and flood: ‘death’s impersonal machinery’ in that fuel-soaked Pig poem. Gin in this poem is a toxic drink (although I believe enjoyable) and an ‘engine’, though the suggestion is as soft as the ‘loom’ we will see in another poem. The best allusion is to The Tempest, for it draws him from the deep grief for his father (now ‘full fathom five’ lying) and given its magical Prospero powers to him:

My god I thought,

the world is so empty

I have peopled it with dreams –[19]

This is an echo for me of this, from Miranda:

However, enough! Just read these poems and love them as I do (or in your own way)!

All love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Oluwaseun Olayiwola (2024) ‘Best Recent Poetry Roundup’ in The Guardian [Fri 5 Jan 2024 07.30 GMT] Available At: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/jan/05/the-best-recent-poetry-review-roundup

[2] Pig in Seán Hewitt (2024: 47) Rapture’s Road London, Cape Poetry, 47.

[3] See ibid respectively: 7, 14, 17, 22,25, 27, 51, 57 (and more of course that is ‘regal, speared, violent’ (ibid: 44) like the Cuchulain of Irish myth).

[4] Night Scented Stock in ibid: 45 (though ‘come and fall with me’ is from Nightfall ibid: 67)

[5] Pleated Inkcaps in ibid: 43

[6] Ibid; 32

[7] Ibid: 51

[8] Ibid: 23

[9] Ibid: 25

[10] Ibid: 26

[11] Ibid: 27

[12] Dogs in ibid: 44

[13] Ibid: 6f.

[14] Dogs in ibid: 44

[15] Ibid: 50

[16] Ibid: 10

[17] Immram ibid: 59

[18] Eleanor Knott & Gerard Murphy (1966: 13) Early Irish Literature London, Routledge & Kegan Paul.

[19] Hewitt 2024 op.cit: 34

2 thoughts on “Queerness, allusion, metaphor and metamorphosis in Seán Hewitt (2024) ‘Rapture’s Road’.”