From September 2021 to September2022, the Frick Museum in New York decided to place each of 4 classic paintings from its collection one by one ‘in conversation’ with a newly commissioned artwork from painters who are currently working and who identify their work as from a queer orientation to the world. Reviewing the publication based on this experiment, Michael Quinn in the Gay and Lesbian Review says: “Pairing paintings might create a “dialogue”, but who decides what these strange bedfellows are saying to each other?”.[1] This blog reflects on Aimee Ng, Xavier F. Salomon & Stephen Truax (Eds.) [2023] Living Histories: Queer Views and Old Masters New York, The Frick Collection [with Lewes (UK), GILES].

Let’s start by looking at two badly reproduced pictures of the rooms in which queer art was shown at the Frick Madison taken from centre-folds of the book published by the Frick Collection. In brief, between the period September 2012 – to September 2022, as each of 4 classic paintings (by Holbein the Younger [two examples thereof], Rembrandt and Vermeer) were loaned to other galleries for their shows, they were replaced temporarily by commissioned works by artists who identified the subject of their current working focus as queer, and were well-known to each other in contemporary art networks, that would ‘converse’ with works with which they would be ‘paired’. In fact, there were two Vermeer paintings he was told intended to face Salman Toor’s contribution, both of which he was asked to respond to (as we see suggested as realised in the top left reproduction in the collage above).

Michael Quinn reviewed this lovely book in the Gay and Lesbian Review (30th Anniversary Issue) and this review persuaded me of the need to have this book as a contribution to representations of queerness in my library. Quinn’s review is balanced and beautiful but is nowhere as insightful as in the quotation I cite in my title. Of course I obviously also thought it so insightful that it begged for elaboration and hence my blog, in order to assimilate the value or otherwise (and I suspect the answer is a mixed bag between those poles) of this experiment in art museum curation.

And I suspect the latter conclusion because this is a book in which the young and emerging artists participating in both exhibition and book seem to have a rather suppressed cause for querying how deep ‘conversation’ (or ‘dialogue’) went. These are rather less foregrounded, perhaps with the exception of Jenna Gribbon’s and Toyin Ojih Odutola’s work which gets a chapter on its own by the guest curator, the Contemporary Art Department Head of the Baltimore Museum of Art, Jessica Bell Brown; brought in by Frick curators; Ng, Salomon and Truax. Her chapter brilliantly makes a superb critical discussion of the concept of ‘colour’ in art history (referencing as necessary the debate between colore and disegno traditions – first distinguished by Georgio Vasari yet sometimes revived in modern masters like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse) and issues of the significance of race and ethnicity in American and global modernity. Because of the quality of this treatment, I incline to favour the two queer artists treated more generally in the curators’ chosen critical essays, Doron Greenberg and Salman Toor .

However, I hope I can give samples from the artist interviews conducted by artists (ones who are their contemporaries and who also always identify with the need to forefront queer subject matter) of what I call of the rather ‘suppressed’ (in varied degree) potential debate material that never quite gets into the summary explications of this experiment in the Frick Madison by the Frick curator-editors, Bell Brown, and, novelist Hanya Yanagihara, actor and art critic Russell Tovey. The hot topics come up in the interviews with each of the four queer artists, which are, I think the most stimulating parts of the book. The reason for this is because of the fact, with which I started this paragraph, that the artists were interviewed by colleagues independent of the curation and editing of the book, but not to ‘queer’ praxis: ‘artists who are their contemporaries and who also always identify with the need to forefront queer subject matter’.

For instance, Toyin Ojih Odutola says she is ‘still processing’ why she agreed to join an exhibition where she and her fellow artists are said to offer ‘Queer Views’ pitted against (as implied in the exhibition subtitle) pictures described as ‘Old Masters’. She identifies in this term implicit concerns that are oppressive; peddling a view that is ‘a very misguided and misapplied view of what art can be’. Nevertheless on this subject Ojih Odutola decided to wait and see the outcome, as silent and attentive as the fictive African Queen in her painting, The Listener (2022). Ojih Odutola is paired in the gallery with Rembrandt Harmensz, van Rijn Self-Portrait (1658) – as in the picture bottom right in the lead collage to this blog – who uses listening itself as form of exercising power. Whilst waiting Ojih Odutola hopes that ‘this project shows the variety that is lacking in “old mastery” thought and teaching. The “old mastery” I was contending with was the legacy of Rembrandt’.[2] Otherwise this notion of ‘mastery’ is not explicitly challenged by the general essays except, as Quinn says, a matter of exclusion corrected by this token inclusion. This is what I understand by how this strategy is expressed, for instance, by Stephen Truax, who says of queer art:

While its overtly sexual imagery and leftist political messaging are familiar in downtown New York galleries, in the silent rooms of the Frick, alongside Old Master paintings. It incites a much stronger reaction. The juxtaposition creates a certain tension: …

The glaring absence of empowered women, of races other than white, and of artists identified as anything but heterosexual is apparent at the Frick, but the introduction of Langberg, Gibbon, Toor, and Ojih Odutola makes the issue unavoidable. [3]

I am reminded in these comments of the predominance in some debates about queer liberation that argue that visibility’ of queer lives is a sufficient strategy of achieving that liberation. The argument is that oppressive attitudes to queer people stem from lack of ‘exposure’ to people who self-identify in this way. Truax seems convinced that to take queer people out of an admittedly large ghetto (‘downtown’ New York) will be enough to inspire constructive debate amongst those holding the majority of power in a society and culture geared mainly for what it thinks of as its ‘élites’. I doubt this proposition very much, in its oppressive assumption of what constitutes both mastery and the different perception of an élite from a downtown population.

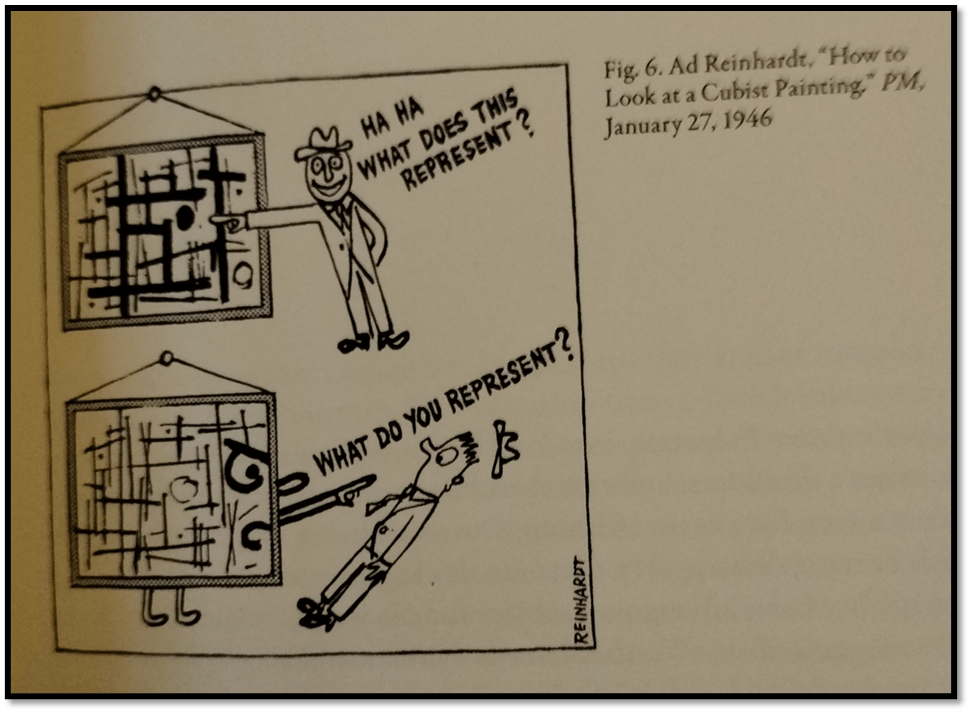

In Salman Toor and Jenna Gribbon’s cases, who both say they were enthusiastic and delighted even to be invited into the Frick by Truax and the others, the suppressed debate as it see it is in the s in the paintings themselves. In Gribbon’s painting, this may be noticed by the curators. I think so because Truax says here of her commissioned work that it was probably done ‘in anticipation of public backlash’). However he does not elaborate that point as I do. [4] Moreover, like Aimee Ng he may think exposure alone works. She says that the pairings created ‘encourages reflection on the roles of portraiture in Holbein’s time and the different functions of portraits of men and women’.[5] But, again here, we are invited to see as curators of the dominant institutions in art THINK that their particular public sees things – here in terms of art-historical perspectives. Our main question is that which asks how the assumptions of viewing have changed under forced exposure of that audience to queer contemporaneity, that may be otherwise unseen or mis-seen by that audience. Truax seems to think, from his use of an Ad Reinhardt cartoon that the painting might do it for itself:

My photograph of a detail of Truax op.cit: 25

But the idea that a painting speaks to you so directly is not sustainable I think from the evidence of most art criticism from most domains I have encountered. Exposure will not nearly punch you in the face in its own right as Reinhardt suggests and cause not only the ‘reflection’ Ng thinks it does. Nor will it make all viewers reflexive about the meanings that sustain your power as a viewer, citizen, taxpayer or ‘customer’ of a viewing gallery where what is on sale is the right to view just as you wish, regardless of the marginalised who may not attend those galleries with you.

My instinct is to believe that it takes MUCH MORE than mere exposure and ‘enhanced’ visibility of the modern queer (and remember for each day that enhancement of supposed visibility was only ONE of the commissioned paintings). All that can appear entirely tokenistic and such evidence can affirm rather than challenge the prejudice of the privileged art viewer, educated entirely in conventional narratives of art-history. It is important that galleries directly address the challenge raised in the content of queer art, perhaps by informatics or by other curational techniques, and not just its silent presence. Those techniques are brilliantly discussed in a booklet on the subject (available at this link). I also addressed less professionally and as a raw learner some issues in blogs I wrote whilst studying art-history in the Open University’s very conventional and unchallenging specialised department, in this area at least for it was once forward thinking (sample them at this link).

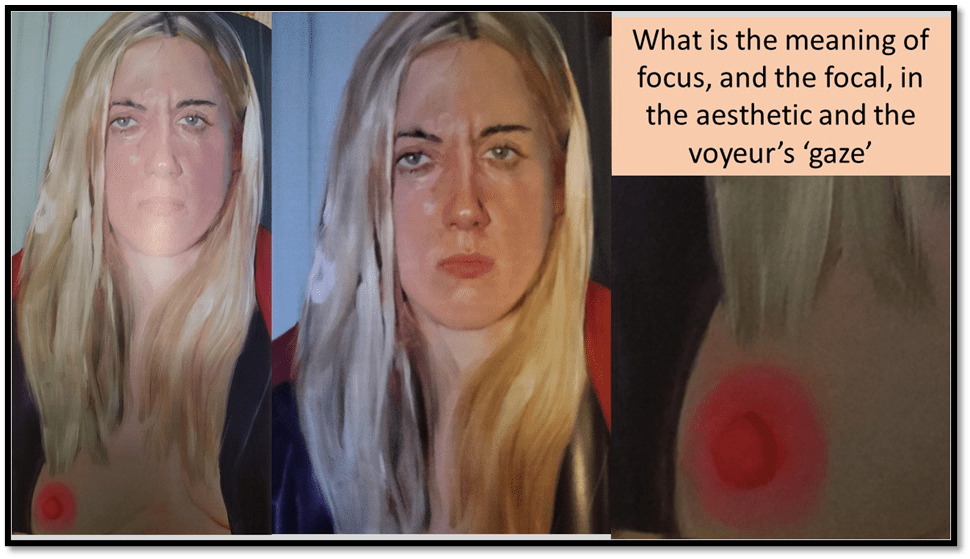

Nevertheless, as Jessica Bell Brown, suggests, there is aggression in her sitter’s gaze (the sitter was her partner and a queer performing artist, a musician, Mackenzie) at the viewer and embodies it her title: What Am I Doing Here? I Should Ask You the Same. Those sentences might be thought to be spoken by the art’s subject (Gribbon’s partner Mackenzie) or the artist themselves and addressed to different audiences. These could be the painting this artist is paired with, Hans Holbein the Younger’s Thomas Cromwell (1532-3), the curators at the Frick, or the Frick’s usual visitors who come into it in order to see ‘classic’ art in the most cases.[6] Gribbon speaks of a childhood to which any art gallery was alien, which even now, on the Frick’s invitation, stimulated an ‘imposter syndrome’. But despite that self-belittling response, at which august institutions are so good at creating – though they are always genuinely (or disingenuously) surprised to hear of them, Gribbon also clearly has some rage that resembles the painting’s version of that in the Ab Reinhardt cartoon: ‘A lot of questions I wanted to pose came from my feelings about being included in this space’. The content of these feelings is, I think of importance to queer art.

As Jessica Bell Brown notes the focus of the feelings may relate to the tension in the painting’s attraction to the gaze, including a gendered gaze. Our gaze may be drawn to the stern face haloed by the dark of a shadow proceeding from unforgiving frontal lighting, or the centrality of the ‘masculinised’ posture of open legs, adorned by rich, almost queenly jewelled hands. But there is no doubt that the strongly coloured nipple, which is enhanced by other colouring contrasts, and which the curator’s call ‘one of Gribbon’s signature neon-pink nipples’.[7] But surely there is more to it being a ‘signature’ than Gribbon alerting us to her presence. We are inclined in art-history to apply that rather old-fashioned tool of invoking the ‘male gaze’ to indicate how a painting distributes focal attractions to the eye, in the service (so the limp theory goes) only of the male gaze instituted by patriarchy, and which subjects female sexuality to male control. However, this nipple is part of the artist’s own engagement, as a queer women with her living and sexual partner. To call it called forth by the male gaze is a major category error, for it is so when we assume paintings directed primarily at men. These readings are present too, but in tension with the painting’s superb and unapologetic queerness (the deliberate plain setting is the home of Gribbon and Mackenzie).

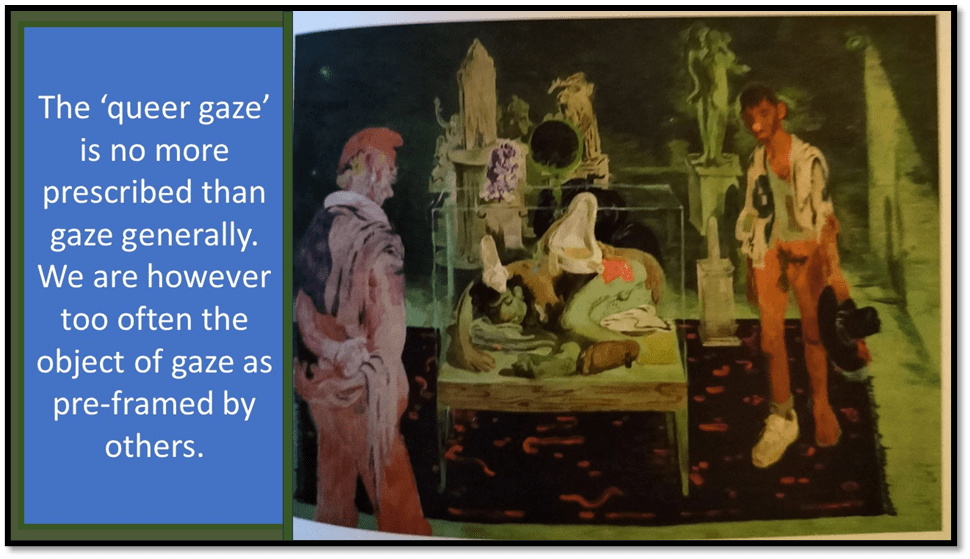

In Salman Toor’s gorgeous painting, two queer men are ‘stuffed very uncomfortably’ into an over-small vitrine together with miscellaneous and cluttered objects, and yet surrounded by classic art, including a lingam – and less celebratedly a simple dildo.[8] The latter is to the side of the figure who seems to be observed as sexual object interestingly, rhyming with its own exposed penis to the delight, we might intuit, of the gazing man of greater riches we see on the left. The set of details below might help us look at the painting again:

The central detail in my collage is that stuffed vitrine, containing objects of mixed association. Though the urinal must recall Duchamp’s early modernist sculpture named ironically Fountain (for both are represented upside down) as we are told in the commentary, it is queered by being full of realistically represented urine, dripping on the queer male subjects from above. There is a ballet slipper, and other objects that play on stereotypes historically used to marginalise queer sexuality as either effete or disgusting. Are we therefore asked to acknowledge her in this ‘fag puddle’ turned artwork by its framing, the fact that queer lives have always been framed historically for a gaze that is not only asked NOT to identify with queerness, but to see such identification as of the marginal and not due the viewer’s regard or respectable. The composition of the queer bodies in it is even aimed at this end. The pale brown figure has his head thrust in the space in which we think the pale green figure’s chest may be. Is this a sexual act – if it fellatio it is hard to configure how, oral nipple-play, or merely a consequence of two bodies having to be squeezed into one small vitrine.

It feels to me to register what it is like to be a ‘queer view’ thrust amongst ‘old masters’. The other objects are, after all traditional, though not in Frick (for Toor distances them from this by making this a museum of sculpture not painting). Where we can find art – robbed usually from the cultures of the world, like that of seventeenth-century Holland that enabled Vermeer’s painting opulence, and placed into Western museums (like the Frick). Such objects include lingams from the Indian sub-continent as well as dido-shaped columns and obelisks from Egyptian ancient cultures. Otherwise, as we see in the whole picture, there is a fair representation of Kouroi ancient and modern (for the Ancient Classical period).

Surely that is a comment on how ‘queer views’ are being asked to represent themselves to the Frick’s clientele. Yet, for me, it is a very great queer painting because it represents these objects in the queer gaze of two queer figures, shown in ways that show the inappropriateness, from a conventional viewpoint, of the presence. The figure on the right as a clown’s nose added and his penis is exposed, though not erect. Only one of his legs is clothed appropriately and covered by trouser-leg and shod with a clean white pump. The other bare foot rhymes with the brown sole in the figure, whose attachment to either man in there seems negotiable. The figure on the left has a naked and shapely bottom(the Catalogue delightfully calls it a ‘buoyant butt’) in clothes which otherwise seem as opulent and anachronistic (he wears a seventeenth-century ruff) as the need to be to recall the clothing in the ‘paired’ couple of Vermeer paintings.[9] Those ‘Old Masters’ are often read as preludes to or possible sexualised encounters by people of different classes.

Yet though the sexual content of Toor’s painting is clearer than Vermeer’s, I think the purpose of mirroring it with the Officer and Laughing Girl (ca 1657) is precisely to utilise art-historical speculation that this is a liaison between a gentleman and serving-class prostitute.[10] Axiomatically at least therefore I read Toor’s position on being displayed as he is surrounded by Old Masters and their lovers (who certainly feel themselves superior) thus in my own words in the collage above: ‘The ‘queer gaze’ is no more prescribed than gaze generally. We are however too often the object of gaze as pre-framed by others’. If I unpacked that axiom, it would say that the playful or lewd possibilities of two people gazing at each are the same for an ‘Old Master’ as a ‘Queer View’. The difference is that queer views are still offered as ‘framed’ and interpreted by both heteronormative and homophobic perspectives, which cause them to look either ‘strange/other’ or, worse, disgusting. For me, this is a wondrous painting (there I said it again).

Likewise, Doron Langberg, when asked why he decided to be paired with Hans Holbein the Younger’s Sir Thomas More (1527) says that Xavier and Aimee assigned the painting to him, an act of top-down decision-making about pairing which painting with each ‘queer view’ that cannot have been unnoticed.[11] The editors do not justify their control other than pragmatically (the paintings were needed because Old Masters were on loan serially) and by assumption (for curators are still thought to operate without too much control coming bottom-up from ‘customers’ nor artist-producers). Of course, though the four ‘old masters themselves were chosen entirely because each had a painting facing them that was being loaned to other galleries during the appropriate period, that does not explain the principle of their allocation between the different artists. Moreover, although I am fanciful in my speculation here, we might imagine that Doron may have sighed somewhat on not ‘dialoguing’ with Rembrandt rather than Holbein. We will never know.

All that aside, you have to congratulate the Frick, and the art historians that staff it, for creating space for the contemporary, relatively lesser-known artists of our time and queerness generally. In fact the book does quite a lot of this self-congratulation for itself in Yanagihara’s Foreword ‘Look at Us’, who first kicks off the concern of most commentators (artists included as you will recognise in the concerns I select from their interviews above) with what Mihael Quinn calls:

questions of inclusion: Whose pictures deserve to hang on a museum’s walls? Is there an institutional responsibility to represent different kinds of art and artists outside the established purview? What types of people are encouraged to walk through a museum’s door?[12]

In a sense Yanagihara was the wrong person to select to open the volume, for her novels are too often (in my view alone) just very long exposures of queer selves to public view (that reminds me of the queer lovers in a vitrine in Salmon Toor’s brilliant painting. It is as if, as Yanagihara puts it the great classics had:

voluntarily moved over and made some room for them on the walls. Look at me, a portrait says, I am here. Someone witnessed me; I witnessed them back. All we have to do is obey.[13]

It is not only that last sentence is grinding in its lack of sensitivity, since the condition of queer persons has too long been that of obeying the demands of institutions except in private. Hence this phrasing hurts (me at least!). it fails to see that queerness has ALWAYS been constructed as something to been look at by others with greater power and authority in matters of sexual conduct and /or representation. These others are those who do not identify with us but who may like to be connoisseurs of our oddness, in dead as well as live specimens, as adornments of their own heteronormative moral ontology. Too often that control is prohibitory and creates false and disgusting or laughable stereotypes. Toor captures what it is like to be that oddness enclosed in noli me tangere glass in his vitrine as I have said. In many ways Ojih Odutola may deal best with this, for she invents a fiction to support her painting of The Listener of a mythical African tribe run by lesbians and served by subjected men. Of course so does Rembrandt have a self-improving myth for his 1658 Self-Portrait, but the fiction is, as the Catalogue of the exhibition says so brilliantly, a myth of monumentality and control that is contradicted entirely by Rembrandt’s wasted gaze at the viewer which is far from exerting power over that observer. The cataloguers say: ‘Rembrandt was bankrupt by the time he painted it. … His pride was fleeting,…’. [14]

In contrast Ojih Odutola’s supporting fiction of an African lesbian queen is supported, as several takes on the picture in this book suggest, by the Queen using not commanding power to rule but by the power of listening, though in our inverted culture to be a weak and passive stance. How wrong that binary is, of course.

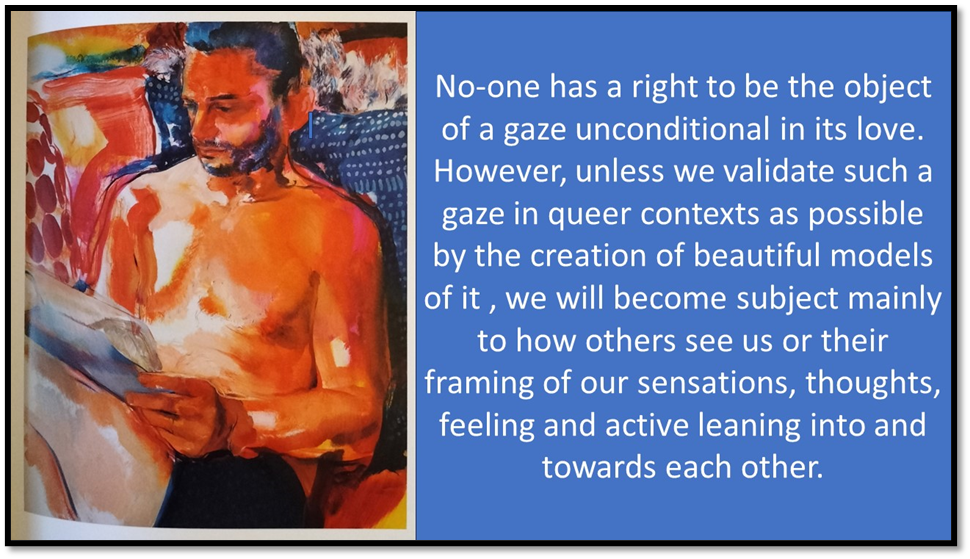

There is so much to explore in this book, despite its small size, but I intend to end with a look at a picture I find exceeding beautiful and yet one that has the potential to undermine some effects of heteronormativity and homophobia. That is the portrait by Doron Greenberg called The Lover. Its painting with Holbein’s Thomas More (1527) helps me very little, brilliant paintings of beautiful men though they both be. Greenberg is correct to see the distinction between them that he wants to emphasise as that between his interior take on a more vulnerable masculinity and Holbein’s concern with powerful exterior look in the face and dress and environment of Thomas More. Such contrasts hardly surprise and are unlikely to have much to say in themselves about queer views of the masculine per se.

What appeals to me, as it would I think any person (male / female / non-binary) attracted to male-identifying persons is the way it uses patterned colour in the whole and in details to register vision in a portrait as a thing of sensation and feeling as well as cognition or anticipation of action. This is a work where the gaze is truly a haptic gaze, a concept devised by the queer eighteenth century connoisseur, Winckelmann, we feel the touch of flesh and embodied structure as well as of emotion.

That hand holds as it feels it invites to be held, at least where the attention of the man to turn from the paperwork he holds. The redness in the skin is a visible thing that gets us absorbed into this man’s passionate subjectivity – is there a reference to his lover in the large papers he holds with such certainty but also softness. The fabrics he wears and rests upon gleam with invitation. This is not only a painting of someone you love, as no-one could ever quite love Holbein’s Thomas More, but who loves the person gazing – artist or viewer, and we feel the glow of his attention, as if from its abstraction in the words he reads.

When I summarised my response to it axiomatically for the collage below I wrote:

No-one has a right to be the object of a gaze unconditional in its love. However, unless we validate such a gaze in queer contexts as possible by the creation of beautiful models of it , we will become subject mainly to how others see us or their framing of our sensations, thoughts, feeling and active leaning into and towards each other.

That will take some unpacking and must deal with the subjective and uncertain as if that mattered too.

However, I have very strong feelings about how heteronormativity and homophobia limit the range of feelings that are possible models for loving interactions between male lovers. Or even those directed to a man by people not identifying as male. For issues like domesticity and passive absorption have been periodically erased from the repertoire of queer love, the fashions seem to go in cycles, and the major levers of this have been the power of toxic masculinities. It is not that empowered hard images of men are not valuable too, for some lovers they are essential. They have however been too long coupled to patriarchal power and its applications and distortions. In this painting hardness and softness negotiate between flesh, fabrics and bone structure, as I have found in some modern queer novels, such as the one at this link, regarding Robert Jones’ The Prophets, a very under-rated novel.

When I taught Health Psychology I used to use evidence from teenage queer boys, who were as disturbed by predominant images of men as powerful, even in their sexual negotiations with each other (the Tom of Finland syndrome), unable to find images of love in either heteronormative or homonormative literatures. This mattered because queerness was, in their experience secreted. Art needed to model this too – even art intended for queer men. It is as if ‘leather biker’ or ‘Daddy’ models of queer male sexuality were all that could be available for these young boys who longed for ‘softness’ too, which seemed forbidden to them. So read my axiom again. I hope what lies behind it is clearer.

No-one has a right to be the object of a gaze unconditional in its love. However, unless we validate such a gaze in queer contexts as possible by the creation of beautiful models of it , we will become subject mainly to how others see us or their framing of our sensations, thoughts, feeling and active leaning into and towards each other.

The creation of such models is the purpose of the art of Doron Greenberg I sampled in this boo (his Bather 2021 is represented) and it perfectly fits the description in the book somewhere of being a painting like unto the method of Bonnard in his bathing subjects, but such as Bonnard could never have painted it. It is a thoroughly queer painting.

In conclusion, I should say that the book does have use for art history, though I felt I had to take this with a big pinch of salt. See for instance the reproduced fold that is pages 38-39 of the book below, from Aimee Ng’s essay ‘Hindsight’, It looks to examples of the failure of homonormative art, even by men often claimed to be exclusively queer such as Michelangelo, represented by his 1540(?) Rape of Ganymede or intended to institutional male queer practices in the courts of some medieval/Renaissance kings, Such as the Triple Profile Portrait (the Mignons of Henry III) of 1570.

However great it is to discover a long history preceding the ‘invention’ of the category ‘homosexual’ as a medical type, it comes at the price of negative associations too, all related to the complicated play in different temporo-spatial cultures of male stereotypes. As I say in my collage above, showing the book pages: ‘Powerless Minions (‘Mignons’) or overpowerful paedophile abduction. Have our sexualities served images of unequal power too long?’ My answer is yes. Only a thorough queer revolution that works against the binaries that cultures have thrust unhelpfully on life will save us.

Of course I could not leave my consideration of this book without a more fulsome statement of admiration for Russell Tovey, whose essay in this book enchants because he is one of the few celebrities who, though he is multi-talented in knowledge about contemporary art and acting (which of course he rightly invokes as knowledge bases, , speaks primarily in it as ‘one of us’, a queer man playing with our common queerness, as in this lovely piece at the end. I live it though it concludes with a kinkily inviting view that is as basically about inclusion as our key strategy to wards liberation, that I have critiqued in others above. For Tovey is Tovey and must be rewarded for his sensitive theatre, film and TV representations of queer men that build bridges across lots of types of masculine self-presentation, many more than in Yanagihara’s world of queer men, who all fall to type.

And yes, you have permission to stare. Stare all you want, take all day if you’d like, be fascinated with these deeply empathetic stories because their truth has been missing from the mainstream for far too long. … Look into their weyes, pore over their clothing, swim in their mysteries, and celebrate, for this infrequent honesty that is becoming more and more commonplace in our museums and on our gallery walls is changing the world. [15]

Do think about buying, keeping and loving this book.

Much love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Michael Quinn (2024: 8) ‘Portraits in Dialog’ in Gay and Lesbian Review (30th Anniversary Issue) Vol. XXXI, No. 1, January-February 2024 Supplement: 8.

[2] Toyin Ojih Odutola (in conversation with Jason Reynolds) [2023: 101] in Aimee Ng, Xavier F. Salomon & Stephen Truax (Eds.) Living Histories: Queer Views and Old Masters New York, The Frick Collection with Lewes (UK), GILES, 101 – 105.

[3] Stephen Truax (2023: 28) ‘“We Can Occupy This Space Now”’ in ibid: 21 – 29.

[4] Ibid: 25 in ibid: 21 – 20.

[5] Aimee Ng (2023: 40) ‘Hindsight’ in ibid: 37 – 43.

[6] Jenna Gribbon (in conversation with Legacy Russell) [2023: 71] in ibid: 59 – 63.

[7] ‘Catalogue’ in ibid: 50

[8] Salman Toor (in conversation with Christopher Y. Lew) [2023: 89] in ibid: 85 – 91.

[9] ‘Catalogue’ op.cit: 78

[10] Stephen Truax (op.cit: 26) says that with appropriate art-historian reserve.

[11] Doron Langberg (in conversation with Jonathan Andrews) [2023: 71] in ibid: 71 – 77.

[12] Michael Quinn op.cit: 8.

[13]Hanya Yanagihara (2023: 9) ‘Look at Us’ in ibid: 7 – 9,

[14] ‘Catalogue’ op.cit: 94

[15] Russell Tovey (2023: 47) ‘The Future Eats the Past, Eats the Future’ in ibid, 45 – 47.