Book into Film: Alasdair Gray’s (1992) Poor Things: Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D., Scottish Public Health Officer Edited by Alasdair Gray and Poor Things, a film directed by Yorgos Lanthimos with screenplay by Tony McNamara (The Favourite). A series of reflections on seeing the film on 15th January 2024 at the Odeon, Durham.

I intend to write a series of reflections on different aspects of the translation of book to film. This is number 2 of 3:

Number 2 of 3 (3rd in process). Book into film: Comparing ‘Queering’ strategies in the novel and film of ‘Poor Things’

For No. I in this series: Book into film: Setting ‘Poor Things’ (use the link)

For No. 3 in this series: Book Into Film: Truth, lies & ‘Poor Things‘.

The film Poor Things ends with a complex ménage established within the home left to Bella by Godwin Bysshe Baxter, her maker, known to her as ‘God’. Ostensibly partnered formerly to Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef), she has incorporated into the household, as well as a group of animals formed by her own learned skills of vivisection – including the goat-brained former husband of the body she inhabits who otherwise aimlessly nibbles at the garden foliage (Christopher Abbott as General Alfie Blessington) – her former colleague in the Paris brothel, Toinette (Suzy Bemba pictured above in the foreground), who is her lover and Socialist mentor. Nothing in this ménage can be expected to fit norms, although it dresses as if it might pass as so doing when its solely human animal members go on their separate ways to the workaday world outside in the fantastical London of the film’s creation. It is a queer resolution to a decidedly queer film that nevertheless appears to pass as a sustainable happy ending that changes the world not at all. The resolutions of the film’s queerness are ones achieved in the home and idyllic garden. ‘God’ is dead, but his spirit presides, with his work carried on by his ‘daughter’, and all are gainfully employed and/or kept wonderfully and fashionably comfortable in the outer world and their own private one. In the care of female hands rather than the odd male couple God and Max, the second female corpse revivified by God (Felicity played by Margaret Qualley) is now blooming. The garden is a kind of private Eden, reserved from troubling norms but, on the other hand not allowed to trouble those norms outside that private space too overtly. Altogether delightful – no loose ends trouble one either as one leaves the cinema or re-examines the film in reflection.

I would call the queerness of the film then a qualified queerness, one that passes in a play where serious things are allowed to be disrupted by the playful and the fantastic as long as they do not contaminate the world we know. The main issues in Bella’s life resolved thus privately are to do mainly with men and the patriarchal systems they espouse, even God to an extent, though he calls his system that of science: Bella has passed through what sexual partnership with men can give and found it, in Duncan Wedderburn limited (though not as entirely wasted in the form of Mark Ruffalo than in the entirely defunct character in the novel – he still looks pretty god, he’s just ‘not enough’), the version of imperialist coercive control in Blessington, even down to the enforcement of ‘clitoridectomy’ to control a female sexuality thought to be too independent) and the Trumpian neoliberal appeal of Jerrod Carmichael as Harry Astley, by far the best looking of these men. Max McCandless is a thoroughly domesticated male with a total lack of controlling jealousy, except in some moments of private refection when apart from Bella.

In doing so, of course, the film breaks every binary category that norms use to order the world and distinguish what is good from what is bad or suspected to be so, including the distinction of the animal and human, private and public, male and female, adult and child, straight or gay and ostensibly black and white. My own feeling is that it does not do this with an eye to any world than that of film culture and its value system, in which the star system remains predominant. It is not that we see norms as performative as Judith Butler might require us that the world is turned into one where all that matters is the quality of the performance, recognisable as that limited by a world of licensed players, who once their role is completed return us to a world we know of celebrity gossip, often despite themselves (this is no personal criticism against them).

Not so, the novel Poor Things, and some of the strategies it uses to queer its world can be evoked here. It is not essentially about the use of the word ‘queer’ in the novel itself. Indeed, the word is there to describe the odd. McCandless had in HIS title for Chapter 3 Gray’s ‘introduction’ says, a phrase pointing to the section on ‘the queer rabbits’, and Gray plays games with this in the text in citing Godwin Baxter’s account of them (they are a black and a white rabbit who are dissected and then put together to form to form two rabbits each half-black and half-white. Moreover they are also of mixed sex/gender: one had ‘male genitals with female nipples, one had female genitals with almost imperceptible nipples (they are pictured on the rear of the hardback dust jacket though the sex markers aren’t made clear – see below):

“… In fact I’ve done something rather shabby. Mopsy and Flopsy were two ordinary, happy little rabbits before I put them to sleep one day and they woke up like this. They are no longer interested in procreation, an activity they once greatly enjoyed”.

Described as ‘little beasts’ that were ‘works of art not nature’, they break all the binaries. McCandless finds the one he holds for a reason unexplained ‘precious’. [1] That preference is as near we get I think to queer identification in McCandless, who appears precisely attracted the liminality he finds here, and perhaps, if Victoria is correct, within himself. The word ‘queer’ is used by the working-class man Blaydon Hattersley later, who is the father of Victoria Blessington , to label those ‘queer in the head’. He feels his daughter can definitely merit the word, as women who flee wealthy men prepared to ‘keep’ them, on their own terms, of course, must be: “… you are queer, Vicky, and the fact that you cannot remember your own dad provers it. Riches or a madhouse! Choose between ‘em”.[2] The issue here is clearly a sociopolitical one equating with the duty of persons to act in accordance with the values of a warped world, where fathers sell their daughters to men rich enough to buy them. But queerness utilises even more basic strategies.

Most of all it relates to the novel’s querying of the basic binary of truth and lie – or fact and fiction – (and I will have much more to say about this in my third blog), for all stories, let alone novels, often live on the cusp of that binary, where queer things are things that break the framework of accepted truth norms. In the novel, this is especially the case in classic Scottish novelists who wear it on their sleeve in a rash of ‘confessional’ novels and a bevy of unreliable narrators, for which we can witness novels known to influence Gray like Hogg’s The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner and Robert Louis Stevenson‘s 1886 novella The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. And the tradition continues in novelists very much influenced by Gray, for example James Robertson‘s 2006 in his novel The Testament of Gideon Mack and Graeme Macrae Burnet’s work. I have blogged in the past on both Robertson and Burnet (see link on their surnames in this sentence). More is to say on this in blog 3 of this series but here I want to show its pertinence to the issue of queer plots. The main narrative of the novel, the only one acknowledged in the film, is meant to be a privately published memoir by Archibald McCandless telling the story of his acquaintance with Godwin Baxter and the progress of his love for God’s creation through vivisection of Bella, though it purports also to witness Bella’s story in her own letters as translated by God, and in some cases reproductions of her own marks in account of herself. The layers of witnessing here are an invitation to both unreliable narration and, to put it bluntly, events so ‘queer’. Even when just out of the ordinary, that they may be lies.

We have already seen, in blog 1, that this air on unreliability is compounded by the presence of a character, based on a historical figure Michael Donnelly but with the same name in the book, whose role as a character is to be the historian who doubts the book’s historical authenticity and lack of paper evidence to support McCandless account of Bella; even the original manuscript, which Gray claims to have lost after being given it by Donnelly to research. Amongst these papers was supposedly a letter added posthumously to those of McCandless by his wife, Victoria, who claims to be the person grossly misrepresented as Bella. And more than that McCandless misrepresents even the appearance and nature of ‘God’, she claims:

Why did my second husband [Archibald, of course for Victoria’s first husband was Blessington, for Bella did not exist according to Victoria] describe Godwin as a monster whose appearance made babies scream, nursemaids flee and horses shy? God was a big sad-looking man, but so careful and alert and unforcing in all his movements, that animals, small people, hurt and lonely people, all women (I repeat and emphasize it) ALL WOMEN AT FIRST SIGHT felt safe and at peace with him.[3]

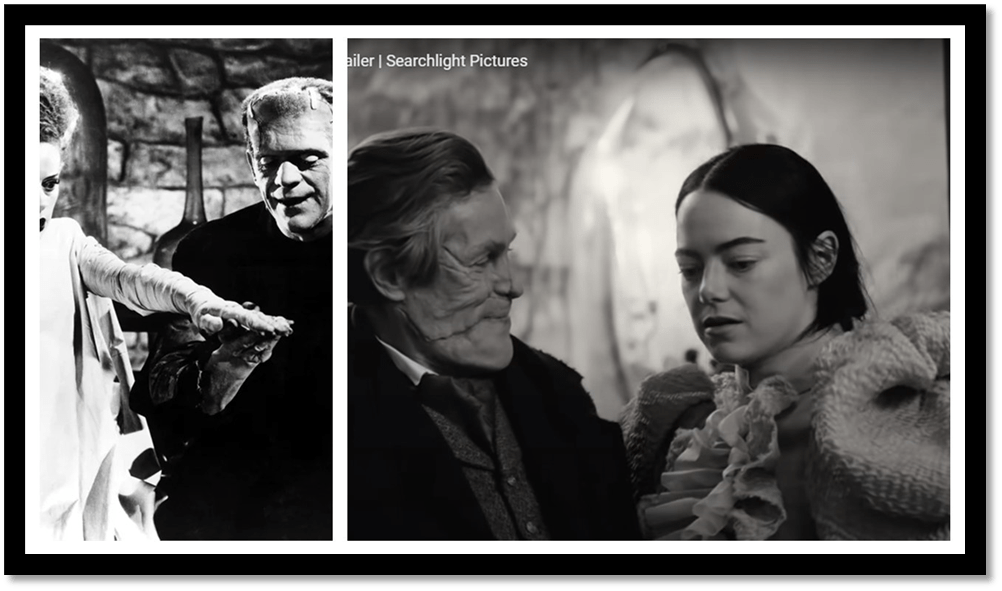

The role of Godwin as a monster is equally fraught in Lanthimos’ film, for that references in the mask of make-up given to William Dafoe to play ‘God’ a reference to the monster created by Frankenstein in the early films wherein Boris Karloff played that monster, based more though on facial structure and scarring than likeness. In the scene where, in the collage below, ‘God’ shows off his ‘monster’, roles can seem to be reversed, though Bella shows no fear of ‘God’ unlike the fear that Elsa Lanchester, herself a monster, has of her male peer in The Bride of Frankenstein.

The point of all of this in both versions of the story is that attraction is queered and obeys no accepted norms, querying the notion of both ‘monstrousness’ and ‘ugliness’. Such a view is, of course, impossible to sustain in a Hollywood film where actors are hired for their beauty or comeliness primarily. For Victoria in the novel, God’s appeal is based on the way he refrains the accepted applied of superior power relations to those with less power – animals, ‘hurt’, ‘lonely’ and ‘small’ people (in size or status) and ALL WOMEN. To be ‘unforcing’ (it is her emphasis in the text is to deny the validity of being on the right side of conventional binaries and to instead inhabit their liminal borders – and that is queer. Dafoe’s ‘God’ in the film does utilise those boundaries of course – he chooses women to make and raise not men and he enforces strict experimental conditions on his scientific subjects (in that sense, though he is shown as a man capable of caring and able to gain the attraction of others (women at least), he remains a less than queer caring tyrant.

In the novel, however, Victoria goes on to give a reason for the bias in McCandless’s (‘her second husband’s’) account of both her and ‘God’ thus. It is a wonderfully queer passage that reinterprets the action of the man’s account in every single respect. God meets Archibald when stands in for the usual lecturer who was sick, in the university anatomy department. It is a momentous meeting, which is somewhat normalised in the film version, though Max McCandles is obviously a would-be teacher’s pet:

Small, awkward McCandless fell as passionately in love with God as I had done. He loved me too, of course, but only because he saw me as God’s female part – the part he could embrace and enter. But God was the first great love of his life, and the love was not returned.[4]

If McCandless represents what he does not understand in himself and his perceptual world as monstrous and ugly, here is a reason Victoria suggests. He needs love that he knows not only is not returned but may never be, in the way he wishes it. The rabbits he found precious later, as I mentioned above are first seen as ‘freaks’.[5] His defence of Bella from what he believes to be Baxter’s ‘ugly’ and socially powerful concupiscence is an embarrassed one that when Godwin looks at him makes him blush: ‘Maybe’: to which God says; “I am an ugly fellow but have you ever known me to do an ugly thing’. This mutual recognition of Godwin’s ugliness is shot through with passion, that need be repressed.[6] For the ‘ugly’ in a society of distorted norms are precisely those who live in or defend marginal cultures. Thus Bella, on her journeys abroad with Wedderburn realises that her allegiance to the values of Punch creates ugly stereotypes of people who are not thus at all: In Punch, the:

ugliest and most comical are Scots, Irish, foreign, poor, servants, rich folk who have been poor till very recently, small men, old unmarried women and Socialists. The Socialists are ugliest, very dirty and hairy with weak chins, …[7]

Admittedly she herself finds the municipal inspector of brothels ‘an ugly little man’ but in this case it is because his role involves the abuse of her lesbian (and socialist) lover, Toinette’s ‘loving-groove’.[8] Here ugliness is what makes the lovely ugly by its failure to see basic truths of humanity and preferring to police the safety of the representatives of the status quo, the rich men who use poor women as prostitutes.

And Archibald’s account is as fulsome a defence of the ménage à trois, or threesome, as is Victoria’s plain statement of the fact that this was a love triangle into which she fitted, only because he had sexual parts a man could the more easily ‘enter’. Victoria is not afraid of polyamory or sexual flexibility. Her first affair, she says, was ‘Sapphic … with my piano teacher in Lausanne’, and like Bella her appreciation of McCandless appears to be because of his sexual endowment (which makes Bella call him ‘Candle’) but her enjoyment of him is for the convenience of a trio: ‘There was no doubt in my mind that God would be overjoyed to get more privacy by sharing me with McCandless’.[9]

When Archibald speaks to Godwin, there is such suppression in the speech, that it seems to be about the emergence of understandings that cross boundaries that prohibit one person from the enjoyment of the body of another. These go a long way in fact to break down lots of conventional boundaries like straight and gay or object and subject, paid prostitute or living spouse, and sometimes ones less easy to contemplate like animal (or machine) / human and child / adult, if only in metaphor for the latter (for the idea of Bella as a sexual child and of very many people as the equivalent of beasts is very strong in the novel and film). When Baxter speaks of seducing Ophelia (from Hamlet) by virtue of his prowess as a scientist of public health mechanisms to be introduced in Elsinore, a joke but one about plumbing, McCandless feels his own inner monstrosity growing about touching ‘a warm living body’ in ‘the dark’ but whose body and is sex/gender a necessary factor as it appears to be in Baxter’s daydreams:

“Daydreams like these, McCandless, accelerated my heart and changed the texture of my skin for hours on end when I was not busy with my studies. A prostitute … would have been a contrivance … a clockwork doll driven by money instead of a spring.”

“But a warm living body, Baxter.”

“I needed to see the expression.”

“In the dark-“ I began to say, but he bade me shut up. I sat feeling more of a monster than he was.[10]

Liliane Louvel in an essay on Poor Things in 2014 has argued that Gray use the Gray’s Anatomy illustrations (aware of the useful suggestion in the sameness of the name Gray) in the book to make points about the structuration of relationships in it. And, if she is right, Gray must have a very conscious decision to challenge norms by fore-fronting queer polyamorous relationships. Louvel points out that at the end of Chapter 6 where Baxter and Bella begin to live together there is a picture from Gray’s Anatomy of two conjoined vertebrae, whereas at the end of Chapter 19 where the three-way relationship begins, there are three conjoined vertebrae in the Gray’s Anatomy illustration.[11]

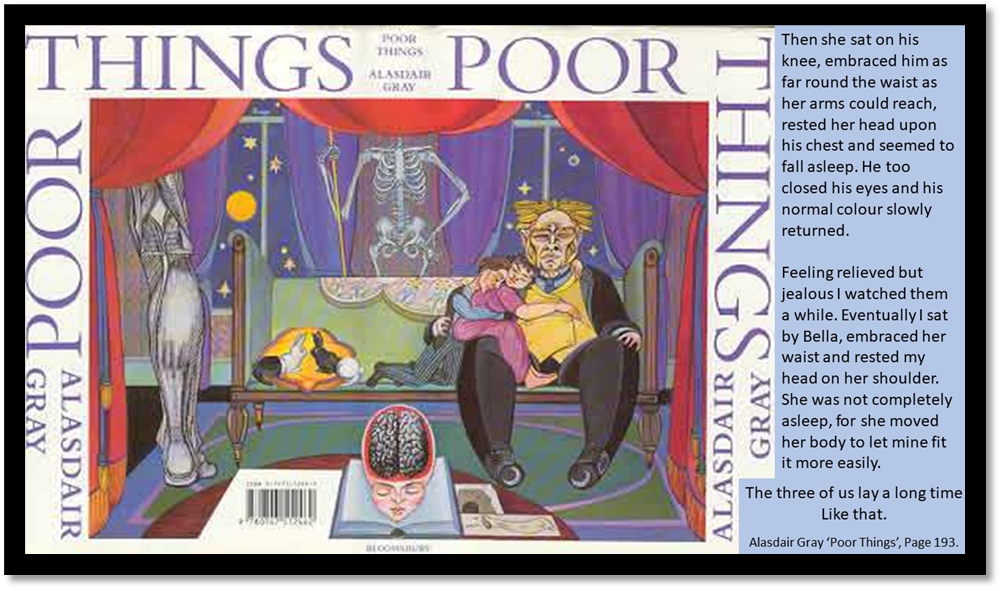

Perhaps, the best scene of a fulfilled but complex threesome is that scene in Chapter 19, ‘My Shortest Chapter’, which Gray chose to illustrate on the continuous back-to-front running dustcover of the hardback (the paperback has the relevant half of it on the front and spine but you miss out on Flopsy and Mopsy, as well as a hybrid arm and leg from Gray’s Anatomy).

Dustcover of the hardback edition and the passage that is illustrated on it.

The dustcover of the hardback edition of Poor Things illustrates that brief part of the beginning of the end of the story of Bella Baxter, I have referred to already. Here, finally a threesome is created, in principle, between Godwin Bysshe Baxter, Bella and Archibald McCandless. Configuring the relationships in the picture, even purely in terms of the ways in which their bodies alone interact and conjoin offers the reader of illustrations some worthwhile puzzles. The rest of the picture, that on the back cover illustrates entirely non-binary hybrids of parts (even the skeleton is divided with left of the spine taking military pose, the right – the skeleton’s left of course) with a rather camp posture of hand flapping from a wrist positioned on the hip – in what might be called the teapot pose associated with the Aesthetic Movement in the 1990s.

In part the puzzle is prompted by the prose description of the scene that I have typed next to the cover picture. It is a picture, as already implied, intended to serve the folded structure of a book’s dust cover, where the threesome take main attention on the front, whilst the spine contains the brain set in a face and resting on a book that divides at the pictured books fold and the gap between the brain’s left and right hemispheres and the spine of the skeleton that stands between the two windows. On the rear are a hybrid of a flayed arm and leg (each taken and collaged on the original from old copies bought on Byres Road, Glasgow, of Gray’s Anatomy he tells us in the account I mention in the next paragraph and Flopsy and Mopsy still non-gendered and perhaps asexual on the same sofa as the threesome, but only seen on the back over of the book.

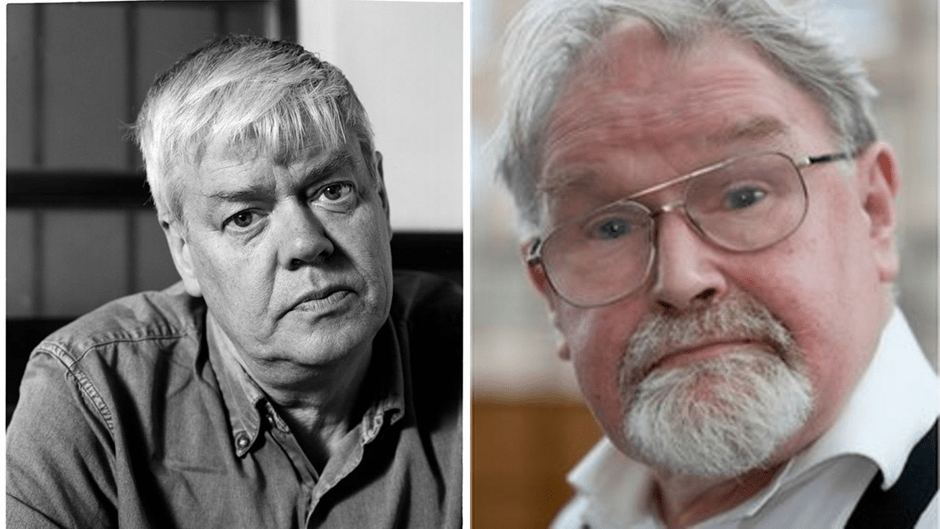

Gray discusses this picture himself in a 2010 retrospective of his pictures, but, as usual, in very throw-away manner. There must be a reason that the night sun is in one window, the moon in another as for the binarily vivisected ‘queer rabbits’ or the dissection of both skeleton (at the spinal column) and the division of brain hemispheres of the medical model brain at the exact centre of the books spine (which also includes a book divided at its centre-fold under the brain, but Gray stays silent.[12] He does however, tell us there that the face of Godwin is based on that of Bernard McLaverty, the Northern Irish novelist, from his own sketch of the writer.

Bernard McLaverty and Alasdair Gray

Whether a likeness or not, what the picture shows, that the description does not, is that God embraces both the man and woman who snuggle to fit in with each and Baxter’s body. This is an achieved queer relationship that will not allow in any principle of division or splitting, such as occurs in every other relationship, and I think this combines the features of masculinity and femininity, for neither Bella nor Archibald are just one or the other but a kind of hermaphroditic hybrid like the ‘queer rabbits’. Queerness covers all kinds of configuration of sexuality. Even Wedderburn thinks he is ‘double’: a ‘noble soul’ and a ‘fiend’, a respectable man of a certain class only sexually excited by a ‘working woman’ available at the level of his bodily self he find ‘disgusting’.[13]

Sometimes the queerness of this text emerges almost contingently, like the silences of the repressed we have seen in McCandless. What, for instance of the two rhyming page folds which place similar images next to each other at the end of a chapter and the graphic creating the next chapter heading page. One chapter concerns Wedderburn is illustrated by Gray’s anatomical drawing of penis and gonads, the other concerns Bella and is of the vagina. Both though are being approached by a large tongue. Neither illustration supports the text Gray ‘pretends’ (or does he?) in 2010 that they are placed there only to give the book ‘period flavour by filling empty space’.[14]

But the aim seems to be to use combinations that valorise both fellatio and cunninglingus and not give the book a ‘period; flavour as a sexually queer one, that divorces sexuality from anything other than a clever combination of body parts.

This same rather playful and impersonal view of bodies in mutually pleasurable interaction is also brilliantly shown in the film, and Emma Stone is at her most brilliant here in combining sexual experience and innocence inside the same actions that she takes part in or invites. However there is not the same tenderness in the film as in the book’s treatment of Bella’s willingness to engage as equally in lesbian relationships. There is, for instance, a kind of unnegotiated violence, like a relationship with a man, when Kathryn Hunter as Madame Swiney, the Paris brothel-keeper twice takes a bite out of Bella’s body. In the novel, this keeper is known to Bella as ‘Millie’ and Bella is as sexually giving to her as to Toinette, regardless of difference of age and looks:

Though plump and queenly she began wailing like a little thin child, so I saw that coaxing, kissing and passionate embraces were required. I led her upstairs to her bedroom while Toinette manned the reception-desk.

But nothing I did cheered her up. ….[15]

I think this less central lesbian relationship here (from the wider range of characters) shows a more socially empathetic view of the function of sexuality divorced from the normative than almost anything that happens in the film, Emma Stone’s brilliance notwithstanding and the beautifully captured relationship with Toinette excepted. How that could have been achieved I do not know, for it is seems that film culture is inevitably caught up in the dynamics of relationships that have some element of abuse of the other, a kind of theft of the body by a gaze that pretends not to be offering titillation but inevitably must. The depiction of the relationship with

The film does, as the book does not, get the relationship between animal and human, particularly hybrid forms of each (the child/adult Bella and the various split animal hybrids) much more strongly and the queerness of all this is a delight, as in the scenes in the collage below.

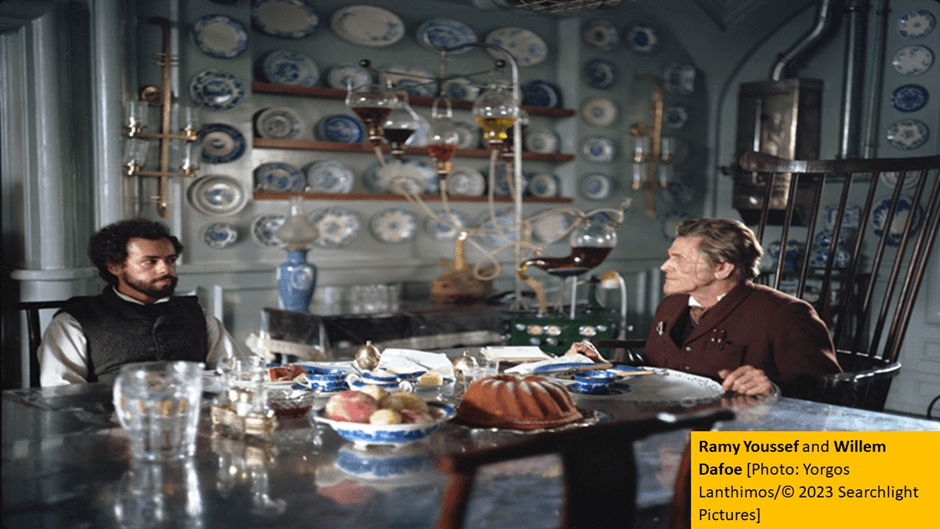

I think I might have liked some suggestion of something ‘other; in the relationship of Godwin and Max, though their domestic scenes as they dine are brilliant. Dinner absorbs into it the need of one person for a mass of ’artificial’ aids used by Godwin to externally replace his lack of an internal bodily apparatus of digestion. These weird systems seem to get absorbed in these charming scenes, as in those visible burps from Godwin, which form bubbles of gas over the table birthed from Godwin’s mouth. All this seems to be absorbed by Max. It is a beautifully queer moment rather than a normalised one, for normalisation always carries a certain embarrassment and patronage with it. Here is clear acceptance and absorption of difference.

In the final blog of this series I will summarise the issue involved in comparing a book with the film it has been formed into around themes of lies and truth, fact and fiction in relation to the belief that identities are not normative and/or prescribed by God or nature but performative. Both artworks have an important contribution to make to that conversation.

Hope to see some of you then

Love Steve

[1] Alasdair Gray (1992:23) Poor Things: Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D., Scottish Public Health Officer Edited by Alasdair Gray London, Bloomsbury Publishing

[2] ibid:224.

[3] ibid:259.

[4] Ibid: 267f.

[5] Ibid: 22

[6] Ibid: 38

[7] Ibid: 127

[8] Ibid: 182

[9] Ibid: 269

[10] Ibid: 40

[11] Liliane Louvel (2014: 188) Itching Etchings: Fooling the Eye or an Anatomy of Gray’s Optical Illusions and Intermedial apparatus’ in Camille Manfredi (Ed.) Alasdair Gray: Ink for Worlds Basingstoke & New York, Palgrave Macmillan 181 – 203.

[12] Alasdair Gray (2010: 242f.) A Life In Pictures Edinburgh, Canongate Books.

[13] Alasdair Gray 1992 op.cit: 77 & 79 respectively

[14] Alasdair Gray 2010 op.cit: 242

[15] Alasdair Gray 1992 op.cit: 183

2 thoughts on “Book into Film: Alasdair Gray’s (1992) ‘Poor Things’ and ‘Poor Things’, a film directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. No. 2 on ‘queering’ in each mode of art.”