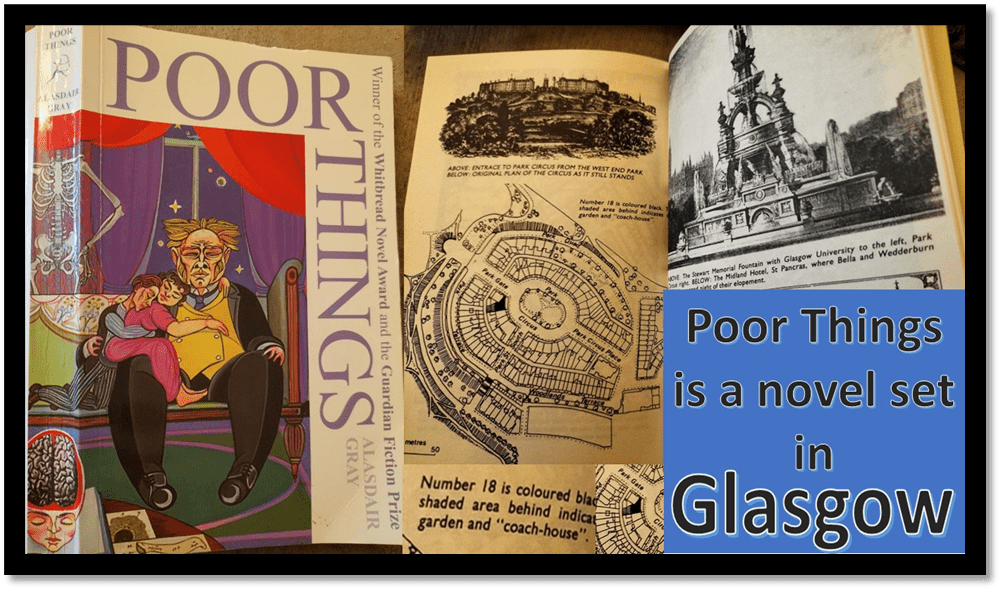

Book into Film: Alasdair Gray’s (1992) Poor Things: Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D., Scottish Public Health Officer Edited by Alasdair Gray and Poor Things, a film directed by Yorgos Lanthimos with screenplay by Tony McNamara (The Favourite). A series of reflections on seeing the film on 15th January 2024 at the Odeon, Durham.

I intend to write a series of reflections on different aspects of the translation of book to film. This is number 1 of 3:

Number 1 of 3 (3rd in process) Book into film: Setting ‘Poor Things’

For No. 2 in this series: Book into film: Queering ‘Poor Things’ (use the link)

For No. 3 in this series: Book Into Film: Truth, Lies and ‘Poor Things’

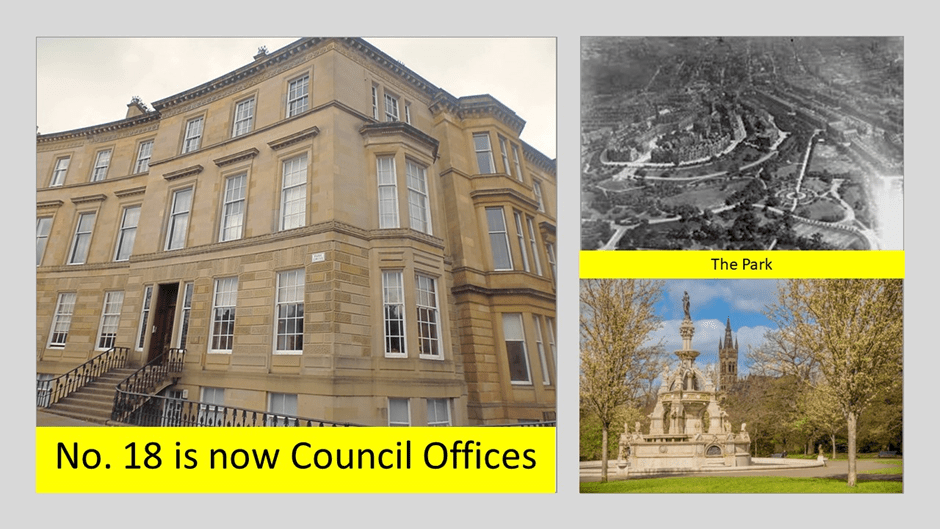

Let’s start with the basic in comparing film and book, for I learned just before going to see the film that it, quite unlike Gray’s novel, never uses Glasgow as a place involved in the story of Bella Baxter, a woman apparently ‘made’ from the corpse of a suicide drawn out of the Clyde and recomposed, using the brain of the child still in her womb, as the woman’s brain. Poor Things: Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D., Scottish Public Health Officer is very definitely a novel set in Glasgow. Bella’s creator, Godwin Bysshe Baxter lives comfortably in Glasgow in the salubrious mansions of Park Circus (at number 18 in fact), still gracious, on the mound overlooking Kelvingrove Museum and the University. Her ideas are limited to that available to her child-like belief in authority, that ‘God’ instils in her, hence her view of poverty is that of the magazine Punch, that ‘only very lazy people are out of work so the very poorest must enjoy being poor’.[1] Hence when she sees poverty shown to her first in Alexandria by Astley she breaks down and regresses from the shock and passion these sights evoke of genuine want.

When she returns to Glasgow, she has become a person looking to improve the world, She is almost a Socialist. Prostrating herself before ‘God’ (Godwin Baxter of course) on her return she bewails her ‘selfish’ failure to care for ‘the scorched and broken victims of heavy industry’. She feels she must return to Alexandria to care for their poor. ‘God’ says that there ‘no need to go so far’ and returns us to an imagined walk into the centre of Glasgow ‘up the High Street from Glasgow Cross’:

To our right you will see railway yards, and warehouses on the ground of the old university where Adam Smith devised his world-famous treatise on The Wealth of Nations and his universally neglected one on Social Sympathy. On the other side a row of ordinary tenements with shops on the ground floor and behind that lie lands of stinking, overcrowded rooms where you will find as much huddled misery as you saw in the sunlight of Alexandria. There are closes where over a hundred people get all their drinking- and washing-water from one communal tap, rooms where a whole family squats in each corner./ The commonest diseases are dysentery, rickets and tuberculosis.[2]

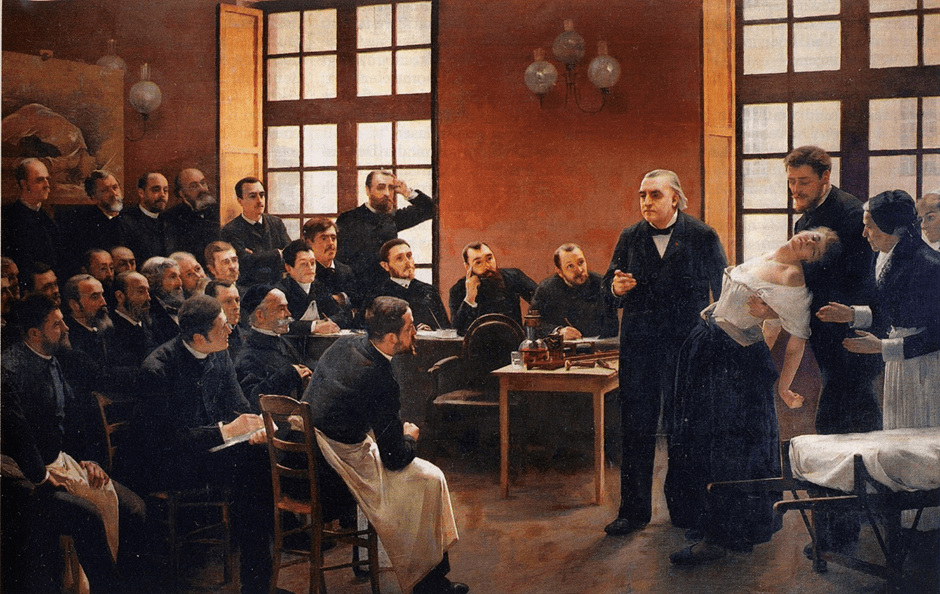

The whole point of ‘God’s’ discourse here is to show that Bella that it is not enough to bare your inner feelings of heightened distress at the plight of starving and dying babies, for whatever reason prompted by your own psychology. That is the way Astley has interpreted her professions of socialism and the way Gray has the rather fraudulent version of Jean-Martin Charcot he creates in the novel analyse her at his Salpêtrière School to which she submits to earn money to escape Paris: that her socialism was reducible to a feminine weakness, a ‘pity for poor people … caused by a displaced sense of motherhood’.[3] Bella in both film and book is ignorant of poverty (and of ‘poor things’) until the child brain God implanted in her grown female body has grown and learned about life, but the danger for Bella (feminine beauty of course is the meaning of her name) is continually tied down to a neurosis aligned to femininity and the failure to acknowledge masculine reason.

The painting “A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière” by Pierre Aristide André Brouillet. This painting shows Charcot demonstrating hypnosis on a “hysterical” Salpêtrière patient, “Blanche” (Marie “Blanche” Wittmann), who is supported by Dr. Joseph Babiński (rear). Note the similarity to the illustration of opisthotonus (tetanus) on the back wall

But this aside (for we will have to return to the portrayal of sex/gender and sexuality in both film and novel in blog number 2) my point is that Bella is a child-brain still developing her education not a woman being shaped by a man (though the processes must in this case be the same) . What she must learn from ‘God’ is that all human beings need to learn to look more closely at the place in which we live and reconfigure its relationship to our sense of what makes any space desirable for human imagination, including our matured political and cognitive-emotional imaginations. This is the reason for mentioning that this place once supported Adam Smith’s development of a ‘phenomenology of morals, describing the workings of our modes of moral judgment as carefully as possible from within, and believing that the comprehensive view that results can itself help guide us in moral judgment’, in the words of the Stanford Philosophical Encyclopaedia’s summary of Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments.[4]

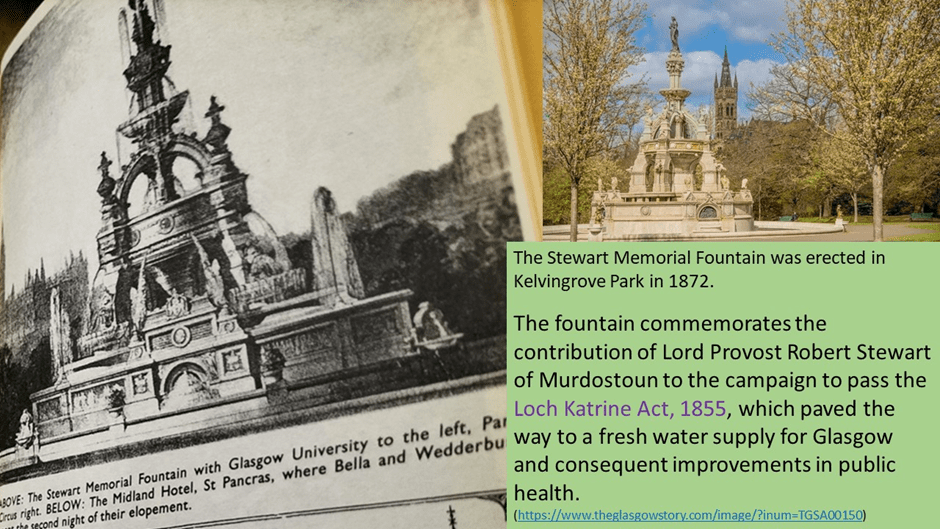

And ‘God’ says attempts to teach Bella this because place (even one you may have lived in for as long as you can remember) only becomes a space for sensation, thought, feeling and action (including moral And political action) when it stops being overfamiliar to us as a ‘place’ and is spatially (and space here is time as well) reconfigured actively in our imaginations. This is how Engels tried to teach his contemporaries to see either Manchester or London, whatever ‘town’ they lived in – penetrating with every active faculty behind, as it were, the facades of the ordinary which we prefer to see and which ideologically replaces the real. Places become spaces for human imagination most when they force the combination in imagination of the need to sense, think, feel and prepare to act upon these things simultaneously. This is the peculiar wisdom of Gray as a novelist who impels into the novel the necessity of political and moral purpose. The ‘Notes Critical and Historical’ in the novel’s appendix are intrinsic to the novel and insist on ‘place’ and its configuration in human terms as a space for activity of all kinds. For, with whatever DryasDust comic pomposity, these ‘notes’ cause you to re-see and reread the passages regarding the setting of the locales of the novel on the pages to which they refer. In one he refers to that scenario that reveals McCandless’ romantic feelings for Bella and distaste for ‘God’ who has current control over her when he meets them both at the Stewart Memorial Fountain.

Pompously in his note on ‘Chapter 7, page 44’, Gray’ in his DryasDust editorial persona gently rebukes McCandless for naming the Fountain wrongly as the ‘Loch Katrine memorial fountain’ instead of the Stewart Memorial Fountain.[5] And as The Stewart Memorial Fountain he labels it in presenting later in the notes a nineteenth century etching of the fountain, contiguously with the label for another Baroque mock-Gothic structure, the St. Pancras hotel in London. He does so just to give historical credence apparently to these locales inhabited briefly by Bella.[6] Yet, Gray is again playacting, drawing the attention of the reader, should they care to notice, to the FACT that McCandless ‘misnames’ the fountain for a reason – for his renaming (not his alone) is after an act of public good in the interests of the whole Glasgow population (he is a working-class origin reforming Liberal in politics) rather than those of the aristocratic functionary it commemorates when named The Stewart Memorial Fountain. McCandless’ naming refers to the 1855 Glasgow Corporation Waterworks Act (popularly known as the Loch Katrine Act), a stepping-stone to the provision of clean water for all in Glasgow.

Moreover, if we peer through the apparent scholarly altercation here, we see that the passage that situates the meeting of McCandless is after all a passage about the poor management of waste material, including excrement, in a Glasgow still designed more for the rich than poor families and individuals, where every detail emphasises the feel of a place requiring reconfiguration by so many activities – mental, moral and political – that pass by the ‘well-dressed people and their children’ who ‘paraded around’ the fountain. Yet the passage calls on every sense (the nose and taste buds, sight and sensation on body surfaces) as well as feeling in order to be appreciated fully and viscerally:

A fortnight of hot calm cloudless summer weather had made Glasgow detestable. With no rain to wash it down or breeze to blow it away the industrial smoke and gases hung in a haze filling the valley to a height of the surrounding hills. A gritty haze that puts a grey film on everything, even the sky, and prickled under the eyelids, and made crusts in the nostrils. … At one point it fell over a weir which churned effluent from a paper-mill into heaps of filthy green froth, each the size of a lady’s bonnet and divided from its neighbour by a crevice floored with opaque scum. This substance (which looked and stank like the contents of a chemical retort) flowed through the West End Park completely hiding the river under it. I imagined the mixture when it entered the oil-fouled Clyde between Partick and Govan, and wondered if men were the only land beasts who excreted into water. Wishing to think pleasanter thoughts I strolled to the Lock Katrine memorial fountain whose up-flung and downward trickling jets gave some freshness to the air.[7]

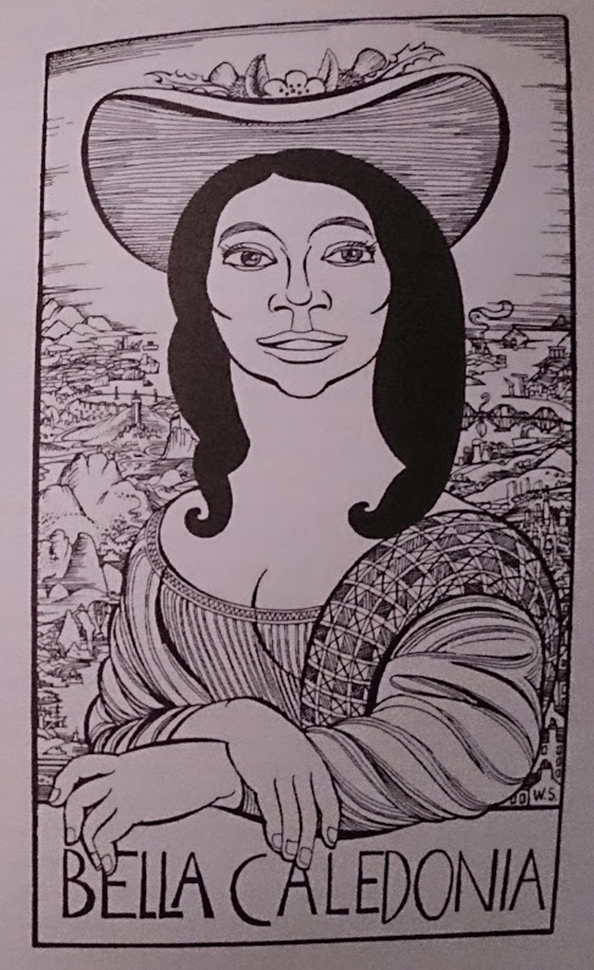

A long passage this but how brilliant in its evocation of repressed action. Likewise, read properly the note which records the neglect of the memorial history of works to the public good, by the entrepreneur friendly Glasgow Labour Council of the time that Gray and other members of the Strickland Distribution (a group of radical artists on the left of politics) hated, of which more below. Even the effluent passes comment on class differences in this passage, for at the fountain McCandless sees Bella. This justifies that the fact in the page facing this passage is one of Gray’s finest politically-satiric book illustrations labelled Bella Caledonia, ostensibly of Bella in a bonnet like the one described in the effluent, but not the ‘purple toque’ she actually wears in the scene. In the illustration Bella looks like a nineteenth-century Mona Lisa but one fronting a rather different landscape. Bella’s shows similar hills and estuaries but also the stinking effluent of industry in that landscape pothering from industrial towers behind her. This may be only for the keenly observant gazer to see, for these details are not all caught by Mike Small in a useful piece on the drawing.[8]

Now the aim of me saying this about the novel is to mourn the decision of director Yorgos Lanthimos’s and writer Tony McNamara, great artists though they are in their own (but not in Gray’s) way, to reset the film of the book. It is all the sadder in the light of what the director told Mark Kermode of his one and only meeting with Alasdair, in preparation for the book:

“… and when I arrived he was there at the door, putting on his jacket. He just said, ‘Follow me!’ and started showing me around Glasgow, very fast! Because the novel takes place in Glasgow, and this was his world. Then we went back to his house and he said, ‘I think you are a talented young man and I would be happy if you want to make my film.’ Then I got back on to the train and went back to London. We never really talked about it again after that.”[9]

There is a kind of violence to Scotland here, not unlike the tendency of film-directors to set Stevenson’s Gothic story of Jekyll and Hyde in London rather than Edinburgh, but worse given what I believe to be the vital living imaginative work by Gray on his Glasgow settings that I have tried to show. I am not alone in feeling this as appears from a piece from the BBC I read before seeing the film and cited in a previewing blog (read at this link if you wish but it is not necessary), which says:

… the film began shooting on a set in Hungary, the Glasgow locations replaced with futuristic versions of Paris, Lisbon and London.

It has led to a frenzied debate on social media about whether the loss of the location has lessened the film.

Pauline McLean (2023), BBC Scotland arts correspondent, available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-67957694

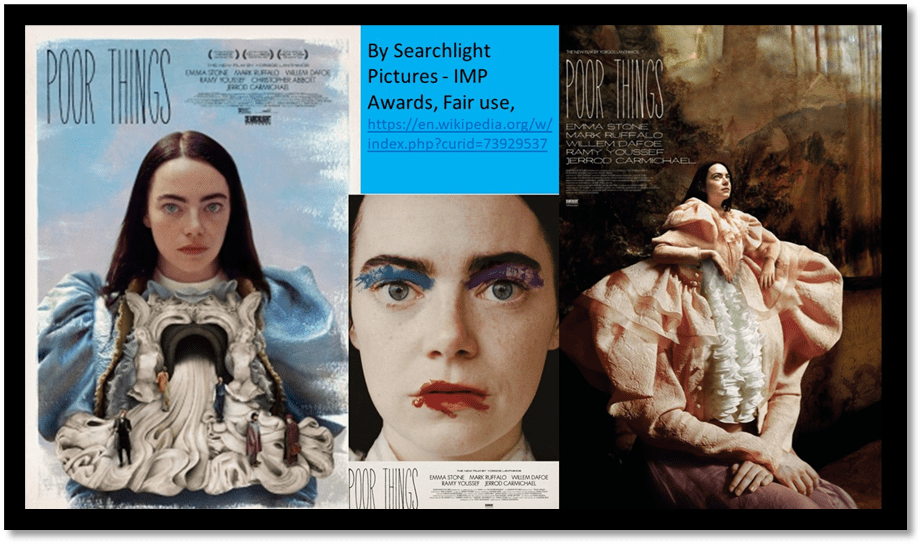

The decision to shoot settings from the imagination of the filmmakers is a sensible option of course, for film is a different medium, employing very different techniques in handling narrative, especially the use of fictional (and unreliable) narrators and ‘points of view’, but it is inevitable that the translation between media will involve some different emphases, perhaps even contradictory to the original medium’s intention, in the finished translation. Indeed – it can’t be translation. As we look at the issues in this series of blogs, we will have to insist that these works should ideally be treated as entirely independent works of art with some interconnections in theme and language but not necessarily of meaning and mission. For every poster in the publicity for the film makes it into a vehicle for the feminist but not greatly the socialist intentions of Gray (the reasons I think that he dedicated the book to his socialist feminist wife, Morag) and does this by greatly abstracting the film from any of the satirical social realism of Gray, as if sex/gender/sexuality relations were best played out in an abstract space. This is easy to see in the collaged posters below, where abstraction of the feminine is aimed for quite directly in various ways, more or less subtle.

In the poster on the left, the landscape (and other characters) emerge from an orifice between the breasts of Emma Stone’s Bella. And this, whether intentional or not, is a brilliant metaphor of the method of the production directors. Wendy Ide in The Observer intelligently sees I think how and why this film is inevitably (despite wonderful male performances in it) a vehicle for a female expert in the art. She says:

But Stone’s virtuoso use of her body – the way it inhabits space, the way she gradually masters her gangling, string-like limbs, the guilelessly open play of emotions in her face – is one of the most crucial elements in our experience of Bella’s journey.[10]

The acting here is not only the crucial but also the probably definitive feature of the film I think, as it dialogues the negotiation of baby girlhood into adulthood, whilst transforming what is understood by femininity and queering it. Francesca Steel in the i newspaper too sees the film in overall summary as a personalised and psychologised thing. It is a ‘magnificent examination of self-discovery’ but also easily generalised as a ‘grand comic tour of sexual awakening’. She is right that Bella, in Stone’s version has to learn that the ‘the world is not all fun’ or sex but this abstracts the importance in it of her learning about what it means to be a ‘poor thing’, in every sense of the word but the metaphoric and personal.[11]

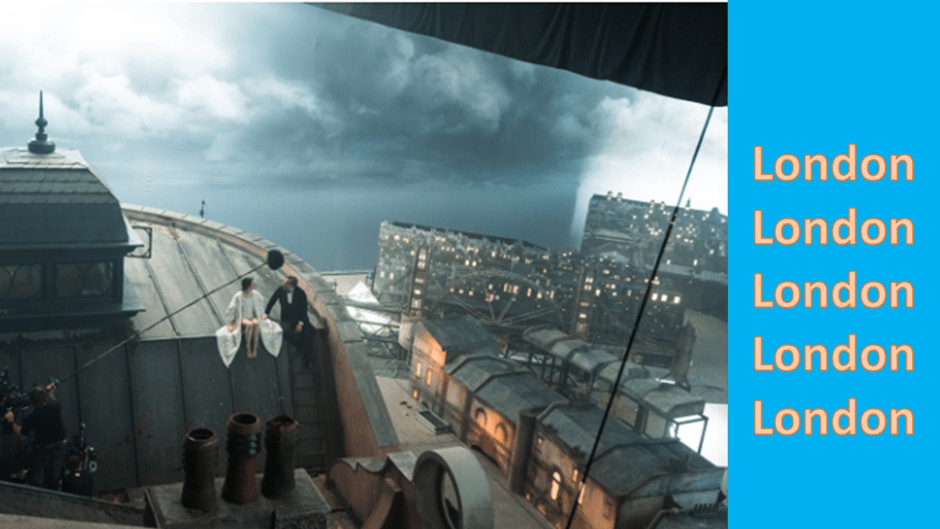

Saleah Blanchaflor (2023) in a piece on the setting of the film in Fast Company online says it in summary as Saleah heard it from the film’s production directors, Shona Heath and James Price: ‘As Bella begins to develop and becomes more curious about the world around her, audiences are taken on a journey through the heroine’s eyes’. Thus, the way in which Bella ‘inhabits space’ in Ide’s terms, is intentionally translated into the film’s settings. In fact this piece shows how enormous sets, created in the huge Etyek Studios in Hungary, with its ‘large soundstage that spans 64, 310 square feet’ were create centripetally around character. They start with London ‘by designing the house, and then the street’, and then, when Bella gets to its roof, from which ‘God’ had banned her, a view of the wider creation of a fantastic world – one such as a child’s imagination might create it in fantasy.Seen in this production shot, we see the process of fantastic creation from an imagined viewpoint we want to share with audiences. Of course, what we see is no more London in the nineteenth century than it is Glasgow, but it is too romanticised in the way a child who wanted nothing but autonomy, not realising its cost, because of an indulgent parent in ‘God’.

All this is planned. As Lanthimos is quoted as saying:

“I suppose to design the house we had to really understand our characters and how [Godwin] would have designed the house around Bella since he was a maverick surgeon. His [Godwin’s] architectural ideas were already unusual, so we started there and grew London into this world.” [12]

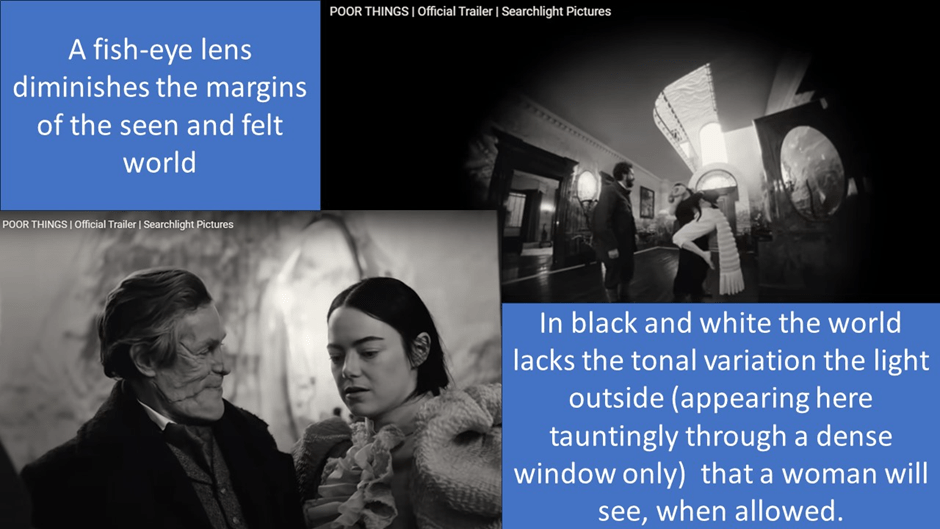

It is not just a matter of sets but of cinematography too. The early film is in black and white and often uses a distorted fisheye lens to distort the world and narrow it in ways that the unexperienced child Bella might feel it. This is not only about conveying the way the world is distorted by patriarchy, although it is that, as Ide says it is, but to capture the sense of the explosion of the senses of the overwhelming world of fantastic and surreal colour Bella enters.

The mental abstraction in the process of creating settings continues in the most ambitious of the hyperreal sets created for the film; that of Lisbon. Wendy Ide, in journalistic fashion rather oversimplifies the fantasy into sexualised fantasy, though that is definitely there, She says:

The world outside, meanwhile, is heavily influenced by art nouveau design. But rather than the flora and fauna that inspired the original artists, here the design takes its cue from earthier themes. Look closely and you’ll notice that phallic imagery abounds, nestling between fallopian curlicues and vulvic buds. It’s a pervert’s playground full of subliminal smut. I can’t think of anywhere I would rather spend my time.[13]

I can live without personal wish as with the art nouveau metaphor, for the architecture of sets is a mix of that, art deco and the Gothic-Baroque of Antoni Gaudi (1852–1926) amongst other mixed periods and styles, as ubiquitous in the film’s Paris as its Lisbon, though the colouring and feel is different. As Shona Heath is cited saying:

“Quite often, we started with a painting for each city to give us a feeling. Lisbon was sort of dusty and magical and a bit candy sweet, while Paris was sort of cold and beautiful like a [Edgar] Degas painting.”[14]

Judge the truth of that statement yourself in the shot of the Paris brothel’s balcony next to Gothic flying buttresses in the Paris shot below, where Bella cements the end of her relationship with now pleading Duncan Wedderburn.

Lisbon is clearly a much more excessive set in every sense of the word, and definitively not intended as a real place. Space exists only in as much as it is sensuously imagined. Bella even has to don dark glasses with marginal shields to see the city without being overwhelmed.

In Lisbon, we will see elements from many periods of history and varied styles within (and between) these periods. This is another reason not to label them ‘art deco’. The flying objects in many littering the sky in many scenes (perhaps public transport vehicles of some futuristic kind) remind us more of utopian and dystopian science fiction , for instance, remind one of Terry Gilliam and even the film Blade Runners. I think Wendy Ide gets it right here when she says: ‘Like much in Poor Things, the period is impossible to pin down exactly. The story of Bella unfolds in a parallel past, a gothic, steampunk-infused Victoriana, a world that is distorted”.[15] And this is not the world of Alasdair Gray but denotes a different conception of art. The use of anachronisms, not only of time but of genre of story-telling type, have other effects.

In the picture of the terrace on which Bella looks down upon fantastical Lisbon, are, to the right from our point of view, a heterosexual couple in late Victorian fashion dress. Over-dressed tourists these, such as England spawned on the ‘Continent’, they draw attention to Bella’s costume as either that of small child (and if so not a girl of the Victorian or Edwardian era for she shows too much flesh) or a more modern tourist, anachronistically out of place. It raise the question of whether she may be seeing things in this Lisbon cityscape that those conventional and dated tourists don’t see. My feeling is that this is indeed so, as it is that, because she situated in the exact middle of the balcony, we as audience are made to realise we can only see Lisbon as she does.

Many of the scenes in the middle of the film take place on ship. Duncan smuggles Bella onto the ship in a trunk (which is not the case in the book). indeed Duncan’s character is entirely different there – Gray’s version being weaker, more febrile, neurotic and sexually exhausted than Mark Ruffalo’s version of him. Both are wonderful, characters – just different ones. Ships are traditionally liminal spaces – and are indeed designed to be in merchant navy tourism – but not quite as liminal as the versions in this film, floating on a sea, obviously artificial (a film set water tank obviously) sometimes digitally coloured and disturbed in fantastic ways that disturb, as are the skies surrounding it.

The deck scenes look like the stage set they were, as seen in this production shot which also shows that some sky colours were projected onto a huge backscreen surrounding the actors’ space.

Interiors on the ship are lush lounges with the air of an aristocratic salon party – full of old ladies keen to talk about penises – although such effects were recreated in real life cruises of the Edwardian period, and even now, though with more infra-dig Carry at Cruising elements. When not in lounges or superior cabins, the ship has some of the best scenes using long enclosed corridors along which Bella walks, recalling scenes from McNamara’s The Favourite, which did the same for Queen Anne. Bella is increasingly aware of being caged and imprisoned despite herself in the film as she comes to adult womanhood.

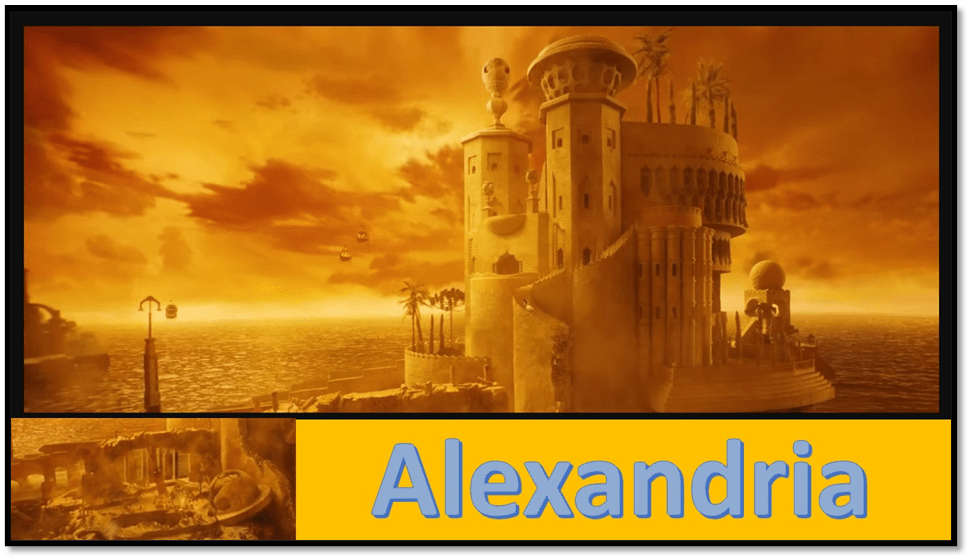

But the star scene setting, in my personal view, is surely that sparse broken tower with staircases that never reach the ground, from which, with Astley, Bella views the Poor Things, people with starving babies, degraded by a structured poverty Punch told her did not exist. This alone stands for the grasp of other people’s extremity of poverty for Bella in the film. She is not taught to see such poverty near home as Gray has ‘God’ do for her in the novel, at least in the narrative we see. And this has consequences because the film understandably misses out the importance to many characters in it – the more positive liberal (not quite yet neo-liberal) economics of Adam Smith and the crude right wing ideology of Thomas Malthus favoured by Astley, that blames poverty on the rank sexual morality, as he saw it, of the degraded poor (a game still being played as you will see in the link). The consequence is that, in the film, Bella’s feeling for the poverty of the masses, leasing her to Fabian liberal socialism, is as psychologised as Charcot would have it in the story as told by Gray.

Alexandria is bathed in a sickly yellow in sea and sky. The rich tourists inhabit huge lounges on a high deck, and the poor are represented symbolically, laying out their babies as they die, in a huge pit, that looks made for the rich merely to view and sail off to more comfortable lives.

Gray makes efforts to avoid the interpretation that is pretty inevitable in the film that Bella’s attitude to poverty is merely an emotional-cognitive state of mind that has no objective reality in the real world. Heath and Price, the production designers admit as much that they see it like Charcot not Gray I think in the film. We never see Alexandria as Cavafy OR E.M. Forster sees it with a real working class and sub-class of the structurally unemployed reduced to poverty by British imperialism. They say that each set ‘required a similar approach to visual details’ to Lisbon even if they were smaller: ‘“We were trying to contrast Lisbon with London, and each time she traveled (sic.) to a different city, we would do that,” Heath said’.

Interior sets will play a part in other themes (although so will these invented ‘exteriors’), hence I will leave their consideration to later sections, even, and especially those concerned with the experimental science laboratory or teaching demonstration, for these are rich and complex.

I think the serious issue of difference I would leave anyone thinking about however, should they wish to, is that, whether intended or not, and though there may be good technical, generic, modal, and aesthetic reasons for changing how setting is referred to and realised, the film’s narrative methods have serious depoliticising effects that would have concerned Alasdair Gray, and about which I think he would have fulminated (he often did so when you met him on the slightest acquaintance such as mine). Glasgow was chosen by him at this period of his writing for a good reason which relates to the spoof conversations with Michael Donnelly at the People’s Palace in Glasgow where Michael was the then curator. The People’s Palace is a miniature baroque building housing the idea of a ‘people’s history’ and Donnelly made it thus.

Much as Donnelly is affectionately fictionalised in the ‘Introduction’ to Poor Things as a curmudgeon and over-scholarly hater of aesthetic values (this was not the case) and enemy of Gray’s support for the truth of the McCandless’ account of Bella. Gray’s first authorised biographer, Rodge Glass, states the case about the ‘Introduction’ to Poor Things simply: ‘His introduction was a lie: …’.[16] There will be more on this in a later blog but not the next, for that one is my queer holiday piece. Donnelly, in fact, was a strong supporter of a mythicising socialist art and commissioned Gray himself in his later curatorship roles, in Dunfermline in 1994-96 for instance. However from 1988 Gray and Donnelly were both heavily involved in debates about representations of Glasgow in the 1990 City of Culture period.

According to Gray and Kelman (Gray’s staunch literary comrade, though of a more anarchic political stance), the City of Culture of 1990 was to be a city where culture was ‘judged by the financial expediency of big business’ (and often misjudged at that), in Kelman’s words, fostered by the then Labour Group on the Council. Moreover, as Kelman goes on to say: ‘When Michael Donnelly attempted to express the reality of what had taken place he was sacked’.[17] At the time all three were involved in an artistic group called the Workers City Group which was involved in challenging the image of Glasgow as The Merchant City, promoted by Labour politicians (deeply distrusted by the left) and cultural leaders. Donnelly also wrote for this group a series of short lives of male and female Glasgow radicals which he called Erased from History, as part of a project that involved Alasdair Gray and James Kelman. This group, later to be a sub-group of the Strickland Distribution already mentioned above says things that are useful in understanding the corollaries in Gray’s life and politics of his making Glasgow feature so strongly in Poor Things, such as the words in this paragraph:

The Workers City group was formed in 1988 as a response to Glasgow’s nomination as the European City of Culture in 1990. The name ‘Workers City’ specifically challenged the contemporary branding of an inner-city area as the ‘Merchant City’; a process whereby a restoration of the reputation of Glasgow’s colonial Tobacco Merchants was made public by Glasgow City Council. Enshrined in numerous Glasgow street names – Buchanan St., Miller St., Ingram St., etc – the Tobacco Lords were deeply implicated in the colonial slave trade, yet the Labour Party-led council have reconstructed a narrative of daring entrepreneurialism for these progenitors, while delivering a cocktail of state-led inducements to the would-be neo-entrepreneurial ‘merchants’ of the present. As author, and Workers City group member, James Kelman put it, however, these same merchants made their money by “the simple expedience of not paying the price of labour”. The name ‘Workers City’ was coined to emphasise the class-based nature of that labour.

From: http://www.workerscity.org/comment.html

The neglect of a real Glasgow of liberal but radical socialist value in the Glasgow Year of Culture was for The Workers City Group was part of a tissue of lies appended to facts that neglected more basic facts that the Workers City Group insisted upon – that the history of Glasgow was more than the history of entitled merchant and professional middle-classes and one in which there were worker heroes as well as victims. These days I think we are so used to the depoliticisation and psychologisation of class conflicts, though it must be partly embraced, we forget how important it is. The result is a first-rate film, which in its settings alone washes socialist history (and history of political economies generally so prominent – if lightly and comically in the novel – down the river, like the effluent in the Kelvin flowing into yet more excremental waste in the Clyde.

I promise the next in the series will be light. It will be, when finished – but yet to be started- about the contrast in queer values between the art forms and plots of both, though admittedly both are savage attacks on binary thinking.

See you then, I hope. All my love.

Steve

[1] Alasdair Gray (1992:135) Poor Things: Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D., Scottish Public Health Officer London, Bloomsbury Publishing.

[2] Ibid: 196

[3] Ibid: 186

[4] https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/smith-moral-political/

[5] Alasdair Gray 1992 op.cit: 283

[6] Ibid: 295.

[7] Ibid: 43f.

[8] Mike Small (2019) ‘Alasdair Gray’s Bella Caledonia’ in Bella Caledonia’ (online) available at: https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2019/12/30/alasdair-grays-bella-caledonia/ . The illustration is on page 45 of the novel.

[9] Yorgos Lanthimos (2023) interviewed by Mark Kermode in ‘My films are all problematic children’ in r (Sun 31 Dec 2023 06.00 GMT ) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/dec/31/yorgos-lanthimos-poor-things-interview-director-favourite-lobster

[10] Wendy Ide (2024) ‘Poor Things review – Emma Stone transfixes in Yorgos Lanthimos’s thrilling carnival of oddness’ in The Observer (Sun 14 Jan 2024 08.00 GMT) available at https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/jan/14/poor-things-review-yorgos-lanthimos-emma-stone-frankenstein

[11] Francesca Steele (2024: 41) A ‘grand comic tour of sexual awakening’ in i newspaper (Friday 12 January 2024), page 41.

[12] Saleah Blanchaflor (2023) ‘The movie ‘Poor Things’ features the year’s most imaginative sets. Here’s how they designed them’ in Fast Company (online 12-08-23). Available at: https://www.fastcompany.com/90993919/the-movie-poor-things-features-the-years-most-imaginative-sets-heres-how-they-designed-them

[13] Wendy Ide, op.cit.

[14] Cited Blanchaflor op.cit.

[15] Wendy Ide op.cit.

[16] Rodge Glass (2008: 222) Alasdair Gray: A Secretary’s Biography London, Bloomsbury Publishing.

[17] James Kelman(1992: 34) ‘Art and Subsidy, the Continuing Politics of Culture City’ in James Kelman Some Recent attacks: essays Cultural and Political Stirling, AK Press, 27 – 36.

3 thoughts on “Book into Film: Alasdair Gray’s (1992) ‘Poor Things’ and ‘Poor Things’, a film directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. This is number 1 of a series and is on the SETTINGS (of novel and film).”